Franz Stigler, a Hero Because He Did Not Shoot by André Ammer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World War I Flying Ace

020065_TimeMachine24.qxd 8/9/01 10:14 AM Page 1 020065_TimeMachine24.qxd 8/9/01 10:14 AM Page 2 This book is your passport into time. Can you survive World War I? Turn the page to find out. 020065_TimeMachine24.qxd 8/9/01 10:14 AM Page 3 World War I Flying Ace by Richard Mueller illustrated by George Pratt A Byron Preiss Book 020065_TimeMachine24.qxd 8/9/01 10:14 AM Page 4 RL4, IL age 10 and up Copyright © 1988, 2000 by Byron Preiss Visual Publications “Time Machine&rdqup; is a registered trademark of Byron Preiss Visual Publications, Inc. Registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark office. Book design by Alex Jay Cover painting by Steve Fastner Cover design by Alex Jay Mechanicals by Mary LeCleir An ipicturebooks.com ebook ipicturebooks.com 24 West 25th St., 11th floor NY, NY 10010 The ipicturebooks World Wide Web Site Address is: http://www.ipicturebooks.com For information address: Bantam Books Original ISBN 0-553-27231-4 eISBN 1-5909-079-3 This text converted to eBook format for the Microsoft Reader. Copyright @ 1988, 2001 by Byron Preiss Visual Publications “Time Machine” is a registered trademark of Byron Preiss Visual Publications, Inc. Registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark office. Cover painting by Steve Fastner Cover design by Alex Jay An ipicturebooks.com ebook ipicturebooks.com 24 West 25th St., 11th fl. NY, NY 10010 The ipicturebooks World Wide Web Site Address is: http://www.ipicturebooks.com Original ISBN: 0-553-27231-4 eISBN: 1-588-24454-7 020065_TimeMachine24.qxd 8/9/01 10:14 AM Page 5 ATTENTION TIME TRAVELER! This book is your time machine. -

106Th AIR REFUELING SQUADRON

106th AIR REFUELING SQUADRON MISSION LINEAGE 106th Aero Squadron organized 27 Aug 1917 Redesignated 800th Aero Squadron, 1 Feb 1918 Demobilized: A and B flights on 8 May 1919, C flight, 2 Jul 1919 135th Squadron organized, 21 Jan 1922 Redesignated 135th Observation Squadron, 25 Jan 1923 Redesignated 114th Observation Squadron, 1 May 1923 Redesignated 106th Observation Squadron, 16 Jan 1924 800th Aero Squadron reconstituted and consolidated with 106th Observation Squadron, 1936 Ordered to active service, 25 Nov 1940 Redesignated 106th Observation Squadron (Medium), 13 Jan 1942 Redesignated 106th Observation Squadron, 4 Jul 1942 Redesignated 106th Reconnaissance Squadron (Bombardment), 2 Apr 1943 Redesignated 100th Bombardment Squadron (Medium), 9 May 1944 Inactivated, 11 Dec 1945 Redesignated 106th Bombardment Squadron (Light), and allotted to ANG, 24 May 1946 Redesignated 106th Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron (Night Photo), 1 Feb 1951 Redesignated 106th Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron, 9 Jan 1952 Redesignated 106th Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron (Photo Jet), 1 May 1957 Redesignated 106th Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron Redesignated 106th Reconnaissance Squadron, 15 Mar 1992 Redesignated 106th Air Refueling Squadron, Oct 1994 STATIONS Kelly Field, TX, 27 Aug 1917 St Maixent, France, 2 Jan 1918 Champ de Tir de Souge, France, 28 Feb 1918-Apr 1919 (headquarters and A Flight) B flight at Camp de Coetquidan, Morbihan, 1 Mar-28 Oct 1918, with detachment thereof at Camp de Meucon, Morbihan, May-Oct 1918; C flight at Le Valdahon, 2 Mar 1918-May -

Bjects Celebrating the 175Th Anniversary of the Georgia Historical Society 2 | GEORGIA HISTORY in TWENTY-FIVE OBJECTS

GEORGIA ISTORY H in 25 OBJECTS Celebrating the 175th Anniversary of the Georgia Historical Society 2 | GEORGIA HISTORY IN TWENTY-FIVE OBJECTS nyone traversing modern-day Georgia will find a land that both resembles and stands in stark contrast to the image of the state in popular culture. From The Colony the towering skyscrapers and traffic jams of Atlanta to the moss-draped oaks Savannah is one of the world’s and quiet, historic squares of Savannah, the state seems a paradox in itself, premier tourist destinations, home comfortably straddling both the old and the new. Somehow, in that uniquely southern to the largest urban National way,A the past and the present merge into one. Georgians may not live in the past, to Historic Landmark district in the paraphrase the historian David Goldfield, but the past clearly lives in Georgians. country. Its stately squares and moss-draped oaks offer one of the Understanding how our world was created—how the past and the present merge—is the most scenic and historic landscapes mission of the Georgia Historical Society. Founded in 1839 as the independent, statewide in America. Its origins lie in the institution responsible for collecting and teaching Georgia and American history, the vision of its founder, James Edward Society has amassed an amazing collection of Georgia-related materials over the past Oglethorpe, and in the artifact seen 175 years, including over 4 million documents, letters, photographs, maps, portraits, rare below—the brass surveyor’s compass books, and artifacts, enough to create a museum of Georgia history. used by Oglethorpe to lay out the city. -

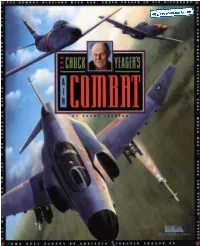

Chuck Yeagers Air Combat - Manual.Pdf

★ AIR COMBAT ★ 1 A DIFFERENT KIND OF COMBAT You’ve spent your life training to be a fighter pilot and dreaming of the day you’d actually get to fly. Hours, weeks, years invested in practice and training. All your hard work and time finally pay off and you develop into a world renown ace. You owe a lot to the flying aces that came before you. The teachers who taught you excellence. You pay them back by teaching other green boys about what it takes to be a flying ace and the edge they need for fighting well. You put back what you took out so more pilots can train and defend the nation. There are, however, some selfish aces out there who don’t give a damn about anyone else. These aces take all they can and say ‘to hell with the pros who came before’. Software publishing is much the same: most consumers pay for their software, but some green boys out there don’t. They copy software and don’t pay their dues to the teams responsible for bringing them the goods in the first place. When that happens, software companies don’t have the money they need to keep turning out the best software they can — some even go under. Electronic Arts is an ace in the field, giving you the best we can. Help us to keep putting out the best by stopping software piracy. As a member of the Software Publishers Association (SPA), Electronic Arts supports the fight against the illegal copying of personal computer software. -

Second Saturday @ Museum SPECIAL VETERANS DAY RECOGNITION PROGRAM for America's Flying Ace New Hampshire's Native Son

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE FROM: Jack Ferns, Executive Director Aviation Museum of New Hampshire 27 Navigator Road Londonderry, NH 03053 (603) 669-4877 Second Saturday @ Museum SPECIAL VETERANS DAY RECOGNITION PROGRAM FOR America’s Flying Ace New Hampshire’s Native Son, Joe McConnell It’s been nearly sixty years since the tragic loss of Dover native and national US Air Force hero Captain Joseph Christopher McConnell Jr. To this day Captain McConnell remains the top American air ace; a triple-ace having recorded 16 shoot-downs of MIGs n the Korean War with F86 Sabre Jets (“MIG:” from the Russian term Mikoyan-Gurevich Design Bureau which was responsible for developing the Soviet aircraft design). McConnell was also the first jet-on-jet fighter ace and ranks among the top ten aces in world aviation history. He was born in Dover in 1922, the son of Joseph C. McConnell Sr. and Phyllis Winfred Brooks, and attended local schools. He started his military career in 1940 when he enlisted the First Infantry Division of the US Army at Fort Devens, Mass. Later he received a transfer to the Air Corps. His dream of becoming a fighter pilot was dashed when instead of going to pilot training he was assigned to navigator school. Upon being certified a navigator, he flew combat missions in World War II in Europe as the navigator on a B-24 Liberator. On August 20, 1942 he married Pearl Edna “Butch” Brown in Fitchburg, Mass. He eventually entered flight training and in 1948 he achieved his goal of becoming a fighter pilot. -

Who Here Wants to Fly? What Are Some of the Requirements to Be a Pilot? • Responses: Flight Training, Knowledge Tests, Practi

Who here wants to fly? What are some of the requirements to be a pilot? • Responses: Flight training, knowledge tests, practical tests, medical certificate Medical certificates required for all certified pilots. Why is that? • Humans are fragile and the flight environment is risky. Flying under normal conditions can stress the body with dehydration, immobility, and jet lag. Flying under extreme conditions can put tremendous strain on the body. Aerial maneuvers in acrobatic or fighter planes can expose pilots to upwards of 12 Gs of force, limiting vision and possibly leading to loss of consciousness. Under the safest, most routine conditions depressurization of an aircraft in an emergency can lead to oxygen deprivation and loss of consciousness. • Pilots need to be in top physical condition and stay healthy to fly ELMENDORF AFB, Alaska -- Four F-15C pilots from the 3rd Wing step to their respective jets July 5 for the fini flight of Maj. Andrea “Gunna” Misener, 19th Figher Squadron, pictured far left. To her right are Capt. Jammie “Trix” Jamieson of the 12th Fighter Squadron, Maj. Carey “Mamba” Jones, 19th Fighter Squadron, and Capt. Samantha “Combo” Weeks, 12th Fighter Squadron. When Maj. Misener worked out who would be joining her in her four- ship fini flight, it became apparent there was a probable first in the Eagle community. Despite the growing number of females who have joined the ranks of fighter pilots since the career opened up to women in 1993, an all-female four-ship had not been accomplished in the F-15C before. Who recognizes that man? C/Tsgts and above will know it’s Eddie Rickenbacker, WWI flying ace and namesake of the fourth achievement in the CAP cadet program. -

A Brief History of the RAF a Brief History of The

A brief history of the RAF A brief history of the RAF Royal air force Creator: Patrick Simon McMahon Contact: [email protected] A brief history of the RAF Legends of the skies Vocabulary Meaning Legend ‘Legend’ here means someone who did something amazing and will be talked about and remembered in history. Remembered in the annals of history This basically means it will be recorded and remembered in history. A flying ace This refers to a pilot that is one of the best pilots. Gallantry This means courageous in battle / being brave in battle. A central figure If you are a ‘central figure’ you are ‘very important’ / ‘a key figure’ in something. A dogfight This means a group of planes attack each other and fight in the sky. Ace-of-aces The best of the best. Exceptional Extraordinary / amazing / unbelievable. Patrolling the skies If you ‘patrol the skies’, you fly around and guard the skies to make sure the area is safe. Never one to shy away from a fight This expression means that someone will never be afraid to fight, no matter what. It’s often used to describe a very brave person. A British WW1 Plane A German WW1 Plane [The Red Barons] Creator: Patrick Simon McMahon Contact: [email protected] A brief history of the RAF Legends of the skies During the first world war two fighter pilots fought for their country and because of their skill and bravery, will forever be remembered in the annals of history. On the British side was Lanoe George Hawker, and on the German side was Manfred Albrecht Freiherr von Richthofen, also known as the "Red Baron". -

DE FRANCE US TOUR March 17 - May 6, 2017 EDITORIAL by the French Air Force Chief of Staff

PRESS PACK - FRENCH AIR FORCE PATROUILLE DE FRANCE US TOUR March 17 - May 6, 2017 EDITORIAL by the French Air Force Chief of Staff is a highly symbolic year for the French and American Air Forces alike. 2017 It marks the centenary of the United States’ entry in the Great War, the 70th anniversary of the founding of the US Air Force, I00 years since the death of Georges Guynemer and, more generally, it is a year in which the French Air Force will commemorate the World War I flying aces. All this goes much deeper than outward symbols and commemorations, it under- scores not only the history of cooperation between our Air Forces, but also the fact that that cooperation is now more topical than ever. During World War I, the French and American airmen of the “La Fayette Escadrille” fought side-by-side, building the superiority in the air that was to play such a decisive role in changing the course first of the Battle of Verdun, then the Battle of the Somme, and then, irreversibly, all the battles which followed. Our aviators continue to fight side-by-side in today’s theaters of operations, protec- ting their fellow citizens. In the Levant, in the same Coalition force deployed to combat Islamic State, they fight the same enemy which has attacked innocent civilians both in France and the US. In the Sahel-Saharan Strip, the US Air Force provides support that enables the French forces to track down jihadist groups in a region the size of Europe and to sustain pressure in areas where they are active, thanks to ongoing air operations. -

Flying Ace Activities

Flying Ace Activities AVIATION CURRICULUM GUIDE FOR MIDDLE GRADE LEVELS 4-6 Edited by: Margaret R. Lindman,Ed.D. Professor Northeastern Illinois University Chicago, Illinois Department of Transportation Federal Aviation Administration Office of Human Resources and Management Washington, D.C. 20591 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS......................................................................................................iii FAA AVIATION EDUCATION REPRESENTATIVES .......................................................iv STUDY PHOTOGRAPHS .................................................................................................... v SELECTED AEROSPACE TOPICS IN CURRICULUM CONTEXT................................... x INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 1 PROPERTIES OF AIR .......................................................................................................... 5 Fluidity....................................................................................................................... 6 Weight........................................................................................................................ 9 Pressure.................................................................................................................... 11 Expansion and Contraction....................................................................................... 17 Water Vapor/Air Holds Moisture............................................................................. -

WINGS OVER NEBRASKA Historic Aviation Photographs

WINGS OVER NEBRASKA Historic Aviation Photographs BY VINCE GOERES with Kylie Kinley and introduction by Roger Welsch Nebraska State Historical Society Books An imprint of the Nebraska State Historical Society Lincoln Cover: Gary Petersen of Walton, Nebraska, flies past Chimney Rock in his 1942 Waco UPF-7 in September 2009. Photograph by Tom Downey, Downey Studio. Opposite: Lt. Paul Wagner and Sgt. Encil Chambers prepare for Chambers’s 1921 record jump of 22,200 feet (see p. 59). Later, at the 1921 American Legion convention in Kansas City, Chambers set a new record with a jump of 26,800 feet. CONTENTS Introduction by Roger Welsch ..........................................viii Preface ..................................................................................x 1. The Early Years................................................................2 2. Fort Omaha Balloon School..........................................14 3. Orville Ralston, Nebraska’s WWI Flying Ace..............20 4. Charles Lindbergh in Nebraska ....................................26 5. Bud Gurney, Nebraska Aviator......................................32 6. Women in Early Nebraska Aviation ..............................38 7. Lincoln’s Commercial Aircraft Builders ......................44 8. Omaha’s Commercial Aircraft Builders........................64 9. Lincoln Airplane and Flying School ............................68 10. Airmail in Nebraska ......................................................78 11. Omaha Municipal Airport (Eppley Airfield) ................92 12. -

WINTER 2010 - Volume 57, Number 4 the Air Force Historical Foundation Founded on May 27, 1953 by Gen Carl A

WINTER 2010 - Volume 57, Number 4 WWW.AFHISTORICALFOUNDATION.ORG The Air Force Historical Foundation Founded on May 27, 1953 by Gen Carl A. “Tooey” Spaatz MEMBERSHIP BENEFITS and other air power pioneers, the Air Force Historical All members receive our exciting and informative Foundation (AFHF) is a nonprofi t tax exempt organization. Air Power History Journal, either electronically or It is dedicated to the preservation, perpetuation and on paper, covering: all aspects of aerospace history appropriate publication of the history and traditions of American aviation, with emphasis on the U.S. Air Force, its • Chronicles the great campaigns and predecessor organizations, and the men and women whose the great leaders lives and dreams were devoted to fl ight. The Foundation • Eyewitness accounts and historical articles serves all components of the United States Air Force— Active, Reserve and Air National Guard. • In depth resources to museums and activities, to keep members connected to the latest and AFHF strives to make available to the public and greatest events. today’s government planners and decision makers information that is relevant and informative about Preserve the legacy, stay connected: all aspects of air and space power. By doing so, the • Membership helps preserve the legacy of current Foundation hopes to assure the nation profi ts from past and future US air force personnel. experiences as it helps keep the U.S. Air Force the most modern and effective military force in the world. • Provides reliable and accurate accounts of historical events. The Foundation’s four primary activities include a quarterly journal Air Power History, a book program, a • Establish connections between generations. -

IWM Duxford Transforms Unseen Historic Rooms to Commemorate Its Role in the Battle of Britain 80 Years On

IWM Duxford transforms unseen historic rooms to commemorate its role in the Battle of Britain 80 years on 13 July – 20 September 2020 #BattleOfBritain80 This summer, IWM Duxford will grant visitors access to newly transformed and previously unseen historic Second World War rooms to retell the story of the Battle of Britain in this 80th anniversary year. Through the opening of The Ops Block: Battle of Britain and reinterpreted areas of the museum, the story of the first major military campaign fought primarily in the air will be explored alongside the historical figures who helped steer the course to victory. Operating as a Sector Station during 1940, RAF Duxford provided support against the relentless assault of the German Luftwaffe during the Battle of Britain which saw intense fighting in the skies and attacks launched at airfields, towns and cities across the country. From 13 July, IWM Duxford will give visitors greater access to the historic site than ever before with the chance to step foot into the Second World War nerve centre of RAF Duxford and hear first-hand accounts of those who lived and worked here in the summer of 1940. Display cases, listening points and a dedicated People Stories Room will tell of the historical significance of The Ops Block and introduce visitors to key ground and air personnel including leading fighter pilot Douglas Bader and members of the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force. An authentic recreation of the 1940s Operation Room will provide a multi-sensory immersion into the tension felt on 15 September 1940, the most action-filled day at RAF Duxford during the Battle of Britain.