The Politics of the Map in the Early Twentieth Century Michael Heffernan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Between France and Romania, Between Science and Propaganda

Between France and Romania, between Science and Propaganda. Emmanuel de Martonne in 1919 Gavin Bowd Abstract: In the aftermath of the Great War, the geographer Emmanuel de Martonne, who began his scientific work in Romania and was a vocal advocate of that country’s intervention in the conflict, placed his knowledge and prestige at the service of redrawing the frontiers of what would become Greater Romania. This article looks at the role of de Martonne as traceur de frontières during the Paris Peace Conference, notably his manipulation of ethnic cartography. At the same time, as this partisan use of “science” shows, de Martonne is also a propagandist for the Romanian cause and post-war French influence. Thus, his confidential reports on the “lost provinces” of Transylvania, Banat, Bessarabia and Dobrogea must be seen in parallel with his published interventions and the place he occupies in a wider Franco- Romanian lobbying network. During the summer of 1919, de Martonne’s participation in a French mission universitaire to Romania plays a diplomatic role at a delicate stage of the Paris negotiations. The fate of his scientific interventions is also subject to the vicissitudes of the war’s aftermath and to the weight of lobbies hostile to Romanian territorial claims, notably on Hungary and Russia, two countries plunged into civil war. The geographer Emmanuel de Martonne, who had been a vocal supporter of Romanian intervention on the side of the Triple Entente and of the creation of a Greater Romania, was not in Europe at the time of the armistice: he was on a mission to the United States from September to December 1918. -

Emmanuel De Martonne, Figure De L'orthodoxie Épistémologique

Emmanuel de Martonne, figure de l’orthodoxie épistémologique postvidalienne ? Olivier Orain To cite this version: Olivier Orain. Emmanuel de Martonne, figure de l’orthodoxie épistémologique postvidalienne ?. Baudelle (Guy), Ozouf-Marignier (Marie-Vic) & Robic (Marie-Claire). Géographes en pratique (1870- 1945). Le terrain, le livre, la cité, Presses universitaires de Rennes, pp.289-311, 2001, Espace et territoires. halshs-00082202 HAL Id: halshs-00082202 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00082202 Submitted on 27 Jun 2006 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Emmanuel de Martonne, figure de l’orthodoxie épistémologique postvidalienne ?1 Olivier Orain « Emmanuel de Martonne a [...] joué en France, et aussi dans la géographie mondiale, un rôle très important. En France il fut le « patron » à une époque où, dans les facultés des lettres, on comptait rarement plus d'un professeur de géographie et, plus rarement encore, un assistant, et où les universités ne s'étaient pas multipliées. » Jean Dresch (1975)2 Il est coutumier dans la tradition française d’opérer une équivalence absolue entre géographie « classique » et « vidalienne », suivant une mythologie que les « élèves » du « maître » ont été les premiers à échafauder. -

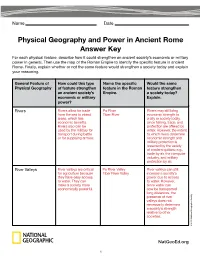

Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer

Name Date Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer Key For each physical feature, describe how it could strengthen an ancient society’s economic or military power in general. Then use the map of the Roman Empire to identify the specific feature in ancient Rome. Finally, explain whether or not the same feature would strengthen a society today and explain your reasoning. General Feature of How could this type Name the specific Would the same Physical Geography of feature strengthen feature in the Roman feature strengthen an ancient society’s Empire. a society today? economic or military Explain. power? Rivers Rivers allow for trade Po River Rivers may still bring from the sea to inland Tiber River economic strength to areas, which has a city or society today, economic benefits. since fishing, trade, and Rivers also can be protection are offered by used by the military for water. However, the extent transport during battle to which rivers determine or for supplying armies. economic strength and military protection is lessened by the variety of modern options: e.g., trade by air, the computer industry, and military protection by air. River Valleys River valleys are critical Po River Valley River valleys can still for agriculture because Tiber River Valley increase a society’s they have easy access power due to access to water. They can to water. However, make a society more since water can economically powerful. now be transported long distances, the presence of river valleys does not necessarily determine a society’s strength relative to other societies. © 2015 National Geographic Society NatGeoEd.org 1 Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer Key, continued General Feature of How could this type Name the specific Would the same Physical Geography of feature strengthen feature in the Roman feature strengthen an ancient society’s Empire. -

Physical Geography of Southeast Asia

Physical Geography of SE Asia ©2012, TESCCC World Geography Unit 12, Lesson 01 Archipelago • A group of islands. Cordilleras • Parallel mountain ranges and plateaus, that extend into the Indochina Peninsula. Living on the Mainland • Mainland countries include Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Laos • Laos is a landlocked country • The landscape is characterized by mountains, rivers, river deltas, and plains • The climate includes tropical and mild • The monsoon creates a dry and rainy season ©2012, TESCCC Identify the mainland countries on your map. LAOS VIETNAM MYANMAR THAILAND CAMBODIA Human Settlement on the Mainland • People rely on the rivers that begin in the mountains as a source of water for drinking, transportation, and irrigation • Many people live in small villages • The river deltas create dense population centers • River create rich deposits of sediment that settle along central plains ©2012, TESCCC Major Cities on the Mainland • Myanmar- Yangon (Rangoon), Mandalay • Thailand- Bangkok • Vietnam- Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon) • Cambodia- Phnom Penh ©2012, TESCCC Label the major cities on your map BANGKOK YANGON HO CHI MINH CITY PHNOM PEHN Chao Phraya River • Flows into the Gulf of Thailand, Bangkok is located along the river’s delta Irrawaddy River • Located in Myanmar, Rangoon located along the river Mekong River • Longest river in the region, forms part of the borders of Myanmar, Laos, and Thailand, empties into the South China Sea in Vietnam Label the important rivers and the bodies of water on your map. MEKONG IRRAWADDY CHAO PRAYA ©2012, TESCCC Living on the Islands • The island nations are fragmented • Nations are on islands are made up of island groups. -

Inscribed 6 (2).Pdf

Inscribed6 CONTENTS 1 1. AVIATION 33 2. MILITARY 59 3. NAVAL 67 4. ROYALTY, POLITICIANS, AND OTHER PUBLIC FIGURES 180 5. SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 195 6. HIGH LATITUDES, INCLUDING THE POLES 206 7. MOUNTAINEERING 211 8. SPACE EXPLORATION 214 9. GENERAL TRAVEL SECTION 1. AVIATION including books from the libraries of Douglas Bader and “Laddie” Lucas. 1. [AITKEN (Group Captain Sir Max)]. LARIOS (Captain José, Duke of Lerma). Combat over Spain. Memoirs of a Nationalist Fighter Pilot 1936–1939. Portrait frontispiece, illustrations. First edition. 8vo., cloth, pictorial dust jacket. London, Neville Spearman. nd (1966). £80 A presentation copy, inscribed on the half title page ‘To Group Captain Sir Max AitkenDFC. DSO. Let us pray that the high ideals we fought for, with such fervent enthusiasm and sacrifice, may never be allowed to perish or be forgotten. With my warmest regards. Pepito Lerma. May 1968’. From the dust jacket: ‘“Combat over Spain” is one of the few first-hand accounts of the Spanish Civil War, and is the only one published in England to be written from the Nationalist point of view’. Lerma was a bomber and fighter pilot for the duration of the war, flying 278 missions. Aitken, the son of Lord Beaverbrook, joined the RAFVR in 1935, and flew Blenheims and Hurricanes, shooting down 14 enemy aircraft. Dust jacket just creased at the head and tail of the spine. A formidable Vic formation – Bader, Deere, Malan. 2. [BADER (Group Captain Douglas)]. DEERE (Group Captain Alan C.) DOWDING Air Chief Marshal, Lord), foreword. Nine Lives. Portrait frontispiece, illustrations. First edition. -

Mistral and Tramontane Wind Speed and Wind Direction Patterns In

Mistral and Tramontane wind speed and wind direction patterns in regional climate simulations Anika Obermann, Sophie Bastin, Sophie Belamari, Dario Conte, Miguel Angel Gaertner, Laurent Li, Bodo Ahrens To cite this version: Anika Obermann, Sophie Bastin, Sophie Belamari, Dario Conte, Miguel Angel Gaertner, et al.. Mistral and Tramontane wind speed and wind direction patterns in regional climate simulations. Climate Dynamics, Springer Verlag, 2018, 51 (3), pp.1059-1076. 10.1007/s00382-016-3053-3. hal-01289330 HAL Id: hal-01289330 https://hal.sorbonne-universite.fr/hal-01289330 Submitted on 16 Mar 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution| 4.0 International License Clim Dyn DOI 10.1007/s00382-016-3053-3 Mistral and Tramontane wind speed and wind direction patterns in regional climate simulations Anika Obermann1 · Sophie Bastin2 · Sophie Belamari3 · Dario Conte4 · Miguel Angel Gaertner5 · Laurent Li6 · Bodo Ahrens1 Received: 1 September 2015 / Accepted: 18 February 2016 © The Author(s) 2016. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract The Mistral and Tramontane are important disentangle the results from large-scale error sources in wind phenomena that occur over southern France and the Mistral and Tramontane simulations, only days with well northwestern Mediterranean Sea. -

A New Geography of European Power?

A NEW GEOGRAPHY OF EUROPEAN POWER? EGMONT PAPER 42 A NEW GEOGRAPHY OF EUROPEAN POWER? James ROGERS January 2011 The Egmont Papers are published by Academia Press for Egmont – The Royal Institute for International Relations. Founded in 1947 by eminent Belgian political leaders, Egmont is an independent think-tank based in Brussels. Its interdisciplinary research is conducted in a spirit of total academic freedom. A platform of quality information, a forum for debate and analysis, a melting pot of ideas in the field of international politics, Egmont’s ambition – through its publications, seminars and recommendations – is to make a useful contribution to the decision- making process. *** President: Viscount Etienne DAVIGNON Director-General: Marc TRENTESEAU Series Editor: Prof. Dr. Sven BISCOP *** Egmont - The Royal Institute for International Relations Address Naamsestraat / Rue de Namur 69, 1000 Brussels, Belgium Phone 00-32-(0)2.223.41.14 Fax 00-32-(0)2.223.41.16 E-mail [email protected] Website: www.egmontinstitute.be © Academia Press Eekhout 2 9000 Gent Tel. 09/233 80 88 Fax 09/233 14 09 [email protected] www.academiapress.be J. Story-Scientia NV Wetenschappelijke Boekhandel Sint-Kwintensberg 87 B-9000 Gent Tel. 09/225 57 57 Fax 09/233 14 09 [email protected] www.story.be All authors write in a personal capacity. Lay-out: proxess.be ISBN 978 90 382 1714 7 D/2011/4804/19 U 1547 NUR1 754 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the permission of the publishers. -

Direction In

What is meant by Direction ? Direction is the information contained in the relative position of one point with respect to another point without the distance information. Directions may be either relative to some indicated reference, or absolute . Direction is often indicated manually by an extended index finger or written as an arrow. On a vertically oriented sign representing a horizontal plane, such as a road sign, "forward" is usually indicated by an upward arrow. ASKING FOR ? DIRECTIONS How do I get to...? How can I get to...? Can you tell me the way to...? Where is...? GIVING DIRECTIONS Go straight on Turn left/right (into … street). Go along /up / down … street Take the first/second road on the left/right It's on the left/right. GIVING DIRECTIONS opposite near next to between at the end (of) on/at/ around the corner behind in front of IIPA , New Delhi We Are Here Near By Location of IIPA WHAT WORDS ARE MISSING? GO _______ GO ON TURN THE STREET GO ____ THE _______ STREET _________ TURN _______ TAKE THE TAKE THE TURN_____ FIRST ON FIRST ON THE _______ THE ________ WHAT WORDS ARE MISSING? Check your answers GO Stright THE Pass through GO UPTHE TURN Around STREET Narrow Bridge STREET TAKE THE TAKE THE TURN right TURN left FIRST ON FIRST ON THE left THE right FILL THE GAPS WITH THE WORDS : A- Excuse me, how Can I get to the castle? B- Go ________ this road, then ________ left and continue for about 100 metres. Then take the second turn on the _________. -

California's Political Geography 2020

February 2020 California’s Political Geography 2020 Eric McGhee Research support from Jennifer Paluch Summary With the 2020 presidential election fast approaching, attention turns to how public views may shape the outcome. California is often considered quite liberal, with strong support for the Democratic Party—but the state encompasses many people with differing political views. In this report, we examine California’s political geography to inform discussion for this election season and beyond. Our findings suggest the state continues to lean Democratic and Donald Trump is unpopular virtually everywhere. As California leans more Democratic in general, conservative Democrats are becoming rarer even in the places where they used to be common; meanwhile, independents, also known as No Party Preference voters, are leaning slightly more Republican in many parts of the state. However, many issues have their own geographic patterns: Most Californians from coast to interior feel their taxes are too high, and Californians almost everywhere believe immigrants are a benefit to the state. Concern about the cost of housing shows sharp divides between the coast and the interior, though Californians are concerned in most parts of the state. Support for the Affordable Care Act (Obamacare) is lukewarm in most places. Even as support for the Democratic Party has strengthened in general, and opinions on some policy issues have grown more polarized in parts of the state, a closer look indicates that registering all eligible residents to vote might actually moderate the more strongly partisan places. Broad Geographic Patterns Today, California is widely understood to be a solidly Democratic state. All statewide elected officials are Democrats, including both United States senators and the governor. -

Earth/Environmental (2014) Released Final Exam

Released Items Fall 2014 NC Final Exam Earth/Environmental Science RELEASED Public Schools of North Carolina Student Booklet State Board of Education Department of Public Instruction Raleigh, North Carolina 27699-6314 Copyrightã 2014 by the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction. All rights reserved. E ARTH/ENVIRONMENTAL S CIENCE — R ELEASED I TEMS 1 Cracks in rocks widen as water in them freezes and thaws. How does this affect the surface of the Earth? A It reduces the rates of soil formation. B It changes the chemical composition of the rocks. C It exposes rocks to increased rates of erosion and weathering. D It limits the exposure of rocks to acid precipitation. 2 How can urbanization affect a local area? A It can increase the number of invasive species in an area. B It can decrease the risk of water pollution in an area. C It can increase the risk of flooding in an area. D It can decrease the need for natural resources in an area. 3 Which is a farming technique that could improve the soil and the environment? A using fueled machines that will turn the soil continuously B creating undisturbed layers of mulch in the soil C placing inorganic chemical fertilizers in the soil D irrigating the RELEASEDsoil with salty water 1 Go to the next page. E ARTH/ENVIRONMENTAL S CIENCE — R ELEASED I TEMS 4 Subsurface ocean currents continually circulate from the warm waters near the equator to the colder waters in other parts of the world. What is the main cause of these currents? A differences in the topography along the ocean floor B differences -

Cartography and the Conception, Conquest and Control of Eastern Africa, 1844-1914

Delineating Dominion: Cartography and the Conception, Conquest and Control of Eastern Africa, 1844-1914 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Robert H. Clemm Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2012 Dissertation Committee: John F. Guilmartin, Advisor Alan Beyerchen Ousman Kobo Copyright by Robert H Clemm 2012 Abstract This dissertation documents the ways in which cartography was used during the Scramble for Africa to conceptualize, conquer and administer newly-won European colonies. By comparing the actions of two colonial powers, Germany and Britain, this study exposes how cartography was a constant in the colonial process. Using a three-tiered model of “gazes” (Discoverer, Despot, and Developer) maps are analyzed to show both the different purposes they were used for as well as the common appropriative power of the map. In doing so this study traces how cartography facilitated the colonial process of empire building from the beginnings of exploration to the administration of the colonies of German and British East Africa. During the period of exploration maps served to make the territory of Africa, previously unknown, legible to European audiences. Under the gaze of the Despot the map was used to legitimize the conquest of territory and add a permanence to the European colonies. Lastly, maps aided the capitalist development of the colonies as they were harnessed to make the land, and people, “useful.” Of special highlight is the ways in which maps were used in a similar manner by both private and state entities, suggesting a common understanding of the power of the map. -

The Politics of Political Geography

1 The Politics of Political Geography Guntram H. Herb INTRODUCTION case of political geography, the usual story is of a heyday characterized by racism, imperialism, and ‘La Géographie, de nouveau un savoir politique’ war in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, (Geography: once again a political knowledge). followed by a period of stagnation and decline in the 1950s, and finally a Phoenix-like revival (Lacoste, 1984) that started in the late 1960s and now seems to be coming to a lackluster end with the cooptation This statement by the chief editor of Hérodote, of key issues of ‘politics’ and ‘power’ by other intended to celebrate the politicization of French sub-disciplines of geography. However, as David geography through the journal in the 1970s and Livingstone has pointed out so aptly, the history of 1980s, also, and paradoxically, captures a profound geography, and by extension, political geography, dilemma of contemporary political geography. If, cannot be reduced to a single story (Livingstone, as a recent academic forum showed, the political 1995). There are many stories and these stories is alive and well in all of geography, does this not are marked by discontinuities and contestations, in question the continued relevance and validity of other words, ‘messy contingencies’, which compli- having a separate sub-field of political geography cate things (Livingstone, 1993: 28). (Cox and Low, 2003)? The most fruitful response A further problem is what one should include to such existential questions about academic sub- under the rubric ‘political geography’: publica- disciplines is delving into the past and tracing the tions of scholars, the work of professional academic genesis of the subject.