The Hip Hop & Obama Reader

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Concert Hall As a Medium of Musical Culture: the Technical Mediation of Listening in the 19Th Century

The Concert Hall as a Medium of Musical Culture: The Technical Mediation of Listening in the 19th Century by Darryl Mark Cressman M.A. (Communication), University of Windsor, 2004 B.A (Hons.), University of Windsor, 2002 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Communication Faculty of Communication, Art and Technology © Darryl Mark Cressman 2012 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2012 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for “Fair Dealing.” Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. Approval Name: Darryl Mark Cressman Degree: Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) Title of Thesis: The Concert Hall as a Medium of Musical Culture: The Technical Mediation of Listening in the 19th Century Examining Committee: Chair: Martin Laba, Associate Professor Andrew Feenberg Senior Supervisor Professor Gary McCarron Supervisor Associate Professor Shane Gunster Supervisor Associate Professor Barry Truax Internal Examiner Professor School of Communication, Simon Fraser Universty Hans-Joachim Braun External Examiner Professor of Modern Social, Economic and Technical History Helmut-Schmidt University, Hamburg Date Defended: September 19, 2012 ii Partial Copyright License iii Abstract Taking the relationship -

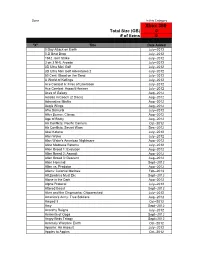

Xbox 360 Total Size (GB) 0 # of Items 0

Done In this Category Xbox 360 Total Size (GB) 0 # of items 0 "X" Title Date Added 0 Day Attack on Earth July--2012 0-D Beat Drop July--2012 1942 Joint Strike July--2012 3 on 3 NHL Arcade July--2012 3D Ultra Mini Golf July--2012 3D Ultra Mini Golf Adventures 2 July--2012 50 Cent: Blood on the Sand July--2012 A World of Keflings July--2012 Ace Combat 6: Fires of Liberation July--2012 Ace Combat: Assault Horizon July--2012 Aces of Galaxy Aug--2012 Adidas miCoach (2 Discs) Aug--2012 Adrenaline Misfits Aug--2012 Aegis Wings Aug--2012 Afro Samurai July--2012 After Burner: Climax Aug--2012 Age of Booty Aug--2012 Air Conflicts: Pacific Carriers Oct--2012 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars Dec--2012 Akai Katana July--2012 Alan Wake July--2012 Alan Wake's American Nightmare Aug--2012 Alice Madness Returns July--2012 Alien Breed 1: Evolution Aug--2012 Alien Breed 2: Assault Aug--2012 Alien Breed 3: Descent Aug--2012 Alien Hominid Sept--2012 Alien vs. Predator Aug--2012 Aliens: Colonial Marines Feb--2013 All Zombies Must Die Sept--2012 Alone in the Dark Aug--2012 Alpha Protocol July--2012 Altered Beast Sept--2012 Alvin and the Chipmunks: Chipwrecked July--2012 America's Army: True Soldiers Aug--2012 Amped 3 Oct--2012 Amy Sept--2012 Anarchy Reigns July--2012 Ancients of Ooga Sept--2012 Angry Birds Trilogy Sept--2012 Anomaly Warzone Earth Oct--2012 Apache: Air Assault July--2012 Apples to Apples Oct--2012 Aqua Oct--2012 Arcana Heart 3 July--2012 Arcania Gothica July--2012 Are You Smarter that a 5th Grader July--2012 Arkadian Warriors Oct--2012 Arkanoid Live -

International Education Journal: Comparative Perspectives Vol

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Sydney: Sydney eScholarship Journals online The International Education Journal: Comparative Perspectives Vol. 18, No 2, 2019, pp. 40-54 https://openjournals.library.sydney.edu.au/index.php/IEJ Pilipinx becoming, punk rock pedagogy, and the new materialism Noah Romero University of Auckland, New Zealand: [email protected] This paper employs the new materialist methodology of diffraction to probe the entanglements of matter and discourse that comprise the assemblage of Pilipinx becoming, or the ways by which people are racialized as Pilipinx. By methodologically diffracting Pilipinx becoming through the public pedagogy of punk rock, this research complicates standard stories of Pilipinx identity to provoke more generative encounters with the Pilipinx diaspora in Oceania. As new materialist theory holds that social life is produced by aggregations of related events, it rejects the notion that ontological becoming is dictated by immutable systemic or structural realities. This application of new materialist ontology contributes to understandings of relationality by demonstrating how Pilipinx identity emerges out of processes of relational becoming comprised of co-constitutive discourses, movements, and materialities of human and nonhuman origin. This approach troubles conceptions of Pilipinx becoming which propose that Pilipinx bodies are racialized through the imposition of colonial mentalities and broadens these theorizations by approaching Pilipinx becoming as a relational process in which coloniality plays a part. This relational conceptualization of Pilipinx becoming is informed by how punk rock, when framed as a form of education, complicates dominant understandings of the contexts, conditions, and capacities of Pilipinx bodies. -

Institute for Studies in American Music Conservatory of Music, Brooklyn College of the City University of New York NEWSLETTER Volume XXXIV, No

Institute for Studies In American Music Conservatory of Music, Brooklyn College of the City University of New York NEWSLETTER Volume XXXIV, No. 2 Spring 2005 Jungle Jive: Jazz was an integral element in the sound and appearance of animated cartoons produced in Race, Jazz, Hollywood from the late 1920s through the late 1950s.1 Everything from big band to free jazz and Cartoons has been featured in cartoons, either as the by soundtrack to a story or the basis for one. The studio run by the Fleischer brothers took an Daniel Goldmark unusual approach to jazz in the late 1920s and the 1930s, treating it not as background but as a musical genre deserving of recognition. Instead of using jazz idioms merely to color the musical score, their cartoons featured popular songs by prominent recording artists. Fleischer was a well- known studio in the 1920s, perhaps most famous Louis Armstrong in the jazz cartoon I’ll Be Glad When for pioneering the sing-along cartoon with the You’ re Dead, You Rascal You (Fleischer, 1932) bouncing ball in Song Car-Tunes. An added attraction to Fleischer cartoons was that Paramount Pictures, their distributor and parent company, allowed the Fleischers to use its newsreel recording facilities, where they were permitted to film famous performers scheduled to appear in Paramount shorts and films.2 Thus, a wide variety of musicians, including Ethel Merman, Rudy Vallee, the Mills Brothers, Gus Edwards, the Boswell Sisters, Cab Calloway, and Louis Armstrong, began appearing in Fleischer cartoons. This arrangement benefited both the studios and the stars. -

Us Military Assistance to Saudi Arabia, 1942-1964

DANCE OF SWORDS: U.S. MILITARY ASSISTANCE TO SAUDI ARABIA, 1942-1964 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Bruce R. Nardulli, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2002 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Allan R. Millett, Adviser Professor Peter L. Hahn _______________________ Adviser Professor David Stebenne History Graduate Program UMI Number: 3081949 ________________________________________________________ UMI Microform 3081949 Copyright 2003 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ____________________________________________________________ ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road PO Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 ABSTRACT The United States and Saudi Arabia have a long and complex history of security relations. These relations evolved under conditions in which both countries understood and valued the need for cooperation, but also were aware of its limits and the dangers of too close a partnership. U.S. security dealings with Saudi Arabia are an extreme, perhaps unique, case of how security ties unfolded under conditions in which sensitivities to those ties were always a central —oftentimes dominating—consideration. This was especially true in the most delicate area of military assistance. Distinct patterns of behavior by the two countries emerged as a result, patterns that continue to this day. This dissertation examines the first twenty years of the U.S.-Saudi military assistance relationship. It seeks to identify the principal factors responsible for how and why the military assistance process evolved as it did, focusing on the objectives and constraints of both U.S. -

Agrarian Reform in the Philippines (Newest Outline)

Politics and Economics of Land Reform in the Philippines: a survey∗ By Nobuhiko Fuwa Chiba University, 648 Matsudo, Matsudo-City, Chiba, 271-8510 Japan [email protected] Phone/Fax: 81-47-308-8932 May, 2000 ∗ A background paper prepared for a World Bank Study, Dynamism of Rural Sector Growth: Policy Lessons from East Asian Countries. The author acknowledges helpful comments by Arsenio Balisacan. Introduction Recent developments in both theoretical and empirical economics literature have demonstrated many aspects of the negative socio-economic consequences of high inequality in the distribution of wealth. High inequality tends to hinder subsequent economic growth (e. g., Persson and Tabellini 1994?), inhibits the poor from realizing their full potential in economic activities and human development through credit constraints (e. g., Deininger and Squire 1998), encourage rent-seeking activities (e. g., Rodrik 1996), and seriously hinder the poverty reduction impact of economic growth (e. g., Ravallion and Dutt ??). The Philippines is a classic example of an economy suffering from all of these consequences. The Philippines has long been known for its high inequality in distribution of wealth and income; unlike many of its Asian neighbors characterized by relatively less inequality by international standards, the Philippine economy has often been compared to Latin American countries which are characterized by high inequality in land distribution. Partly due to its historically high inequality there has long been intermittent incidence of peasant unrest and rural insurgencies in the Philippines. As a result, the issue of land reform (or ‘agrarian reform’ as more commonly called in the Philippines, of which land reform constitutes the major part) has continuously been on political agenda at least since the early part of the 20th century; nevertheless land reform in the Philippines has been, and still is, an unfinished business. -

Agrarian Reform and the Difficult Road to Peace in the Philippine Countryside

Report December 2015 Agrarian reform and the difficult road to peace in the Philippine countryside By Danilo T. Carranza Executive summary Agrarian reform and conflict in the rural areas of the Philippines are closely intertwined. The weak government implementation of the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program, inherent loopholes in the law, strong landowner resistance, weak farmers’ organisations, and the continuing espousal by the New People’s Army of its own agrarian revolution combine to make the government’s agrarian reform programme only partially successful in breaking up land monopolies. This is why poverty is still pronounced in many rural areas. The rise of an agrarian reform movement has significantly contributed to the partial success of the government’s agrarian reform programme. But the government has not been able to tap the full potential of this movement to push for faster and more meaningful agrarian reform. The agrarian reform dynamics between pro- and anti-agrarian reform actors create social tensions that often lead to violence, of which land-rights claimants are often the victims. This is exacerbated and in many ways encouraged by the government’s failure to fulfil its obligation to protect the basic human rights of land-rights claimants. This report outlines the pace and direction of agrarian reform in the Philippines and its role in fighting poverty and promoting peace in rural areas. It emphasises the importance of reform-oriented peasant movements and more effective government implementation to the success of agrarian reform. The report also asserts the need for the government and the armed left to respect human rights and international humanitarian law in promoting the full participation of land-rights claimants in shaping and crafting public policy around land rights. -

![THE HUMBLE BEGINNINGS of the INQUIRER LIFESTYLE SERIES: FITNESS FASHION with SAMSUNG July 9, 2014 FASHION SHOW]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7828/the-humble-beginnings-of-the-inquirer-lifestyle-series-fitness-fashion-with-samsung-july-9-2014-fashion-show-667828.webp)

THE HUMBLE BEGINNINGS of the INQUIRER LIFESTYLE SERIES: FITNESS FASHION with SAMSUNG July 9, 2014 FASHION SHOW]

1 The Humble Beginnings of “Inquirer Lifestyle Series: Fitness and Fashion with Samsung Show” Contents Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ................................................................ 8 Vice-Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ....................................................... 9 Popes .................................................................................................................................. 9 Board Members .............................................................................................................. 15 Inquirer Fitness and Fashion Board ........................................................................... 15 July 1, 2013 - present ............................................................................................... 15 Philippine Daily Inquirer Executives .......................................................................... 16 Fitness.Fashion Show Project Directors ..................................................................... 16 Metro Manila Council................................................................................................. 16 June 30, 2010 to June 30, 2016 .............................................................................. 16 June 30, 2013 to present ........................................................................................ 17 Days to Remember (January 1, AD 1 to June 30, 2013) ........................................... 17 The Philippines under Spain ...................................................................................... -

Russia-US Power Struggle for Unpredictable Central Asia

Russia-US power struggle for unpredictable Central Asia Nikola Ostianová Abstract: Th e article focuses on a struggle between the Russian Federation and the US for Central Asian countries states — Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. Th e time settings of the topic encompass period between the collapse of the So- viet Union and the year 2011. Th e paper focuses on a development of a politico-military dimension of the relation between the two Cold War adversaries and Central Asia. It is divided into six parts which deal cover milestone events and issues which infl uenced the dynamics of the competition of Russia and the US in Central Asia. It is concluded that despite of the active engagement of Russia and the US neither of them has been able to gain loyalty of Central Asian countries. Keywords: Central Asia, Russia, the US, military base, security, struggle Introduction A struggle of the Russian Federation and the United States for independent coun- tries in Central Asia — a new Great Game1 — has sparkled after the end of the Cold War. Th e rivalry is characterised by Russia’s eff orts to maintain the infl uence on its former Soviet satellite states — Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan — and the US interest in building yet another of its power bases — this time in the Central Asian region. Th e main goal of the article is to analyse this struggle of Russia and the US in Central Asia with a focus on the politico-military Contemporary European Studies 1/2016 Articles 45 dimension in the timeframe which takes into consideration a period from the end of the Cold War until 2011. -

TPP-2014-08-Power Struggle

20 INTERNATIONAL PARKING INSTITUTE | AUGUST 2014 POWER STRUGGLE Charger squatting is coming to a space near you. Are you ready? By Kim Fernandez HAPPENS ALL THE TIME: Driving down the road, you glance at your fuel gauge to see it’s nearly empty. You pull into the gas station, line up behind IT the car at the pump, and see there’s nobody there actually pumping gas. Maybe that driver is in the convenience store or the restroom or off wandering the neighborhood—who knows? But they’re not refueling; they are blocking the pump, heaven only knows how long they’ll be gone, and you still need gas. Frustrating? You bet. Now transfer that scenario to a parking garage or lot, swap out your SUV for a Nissan Leaf, and picture that gas pump as an electric vehicle (EV) charger that’s blocked by a car that’s not charging. The owner could come back in an hour or a day. There’s no way to tell. But it’s the only charger in the facility, and you need it. DREAMSTIME / HEMERA / BONOTOM STUDIO / HEMERA BONOTOM DREAMSTIME The City of Santa Monica installed signage on its EV charging stations with time limits and other regulations. FRANK CHING Parking a non-charging car at a charger for hours or As EVs become more popular, squatting grows as an days is called “charger squatting,” and the resulting anger issue. Those who’ve already dealt with it say it’s still fairly that builds up in a driver who needs it has been christened new ground, but there are some ways to discourage parking “charger rage.” Both are growing problems that will affect at chargers when a vehicle isn’t actively charging, without parking professionals if they haven’t already. -

Air & Space Power Journal, July-August 2012, Volume 26, No. 4

July–August 2012 Volume 26, No. 4 AFRP 10-1 International Feature Embracing the Moon in the Sky or Fishing the Moon in the Water? ❙ 4 Some Thoughts on Military Deterrence: Its Effectiveness and Limitations Sr Col Xu Weidi, Research Fellow, Institute for Strategic Studies, National Defense University, People’s Liberation Army, China Features Toward a Superior Promotion System ❙ 24 Maj Kyle Byard, USAF, Retired Ben Malisow Col Martin E. B. France, USAF KWar ❙ 45 Cyber and Epistemological Warfare—Winning the Knowledge War by Rethinking Command and Control Mark Ashley From the Air ❙ 61 Rediscovering Our Raison D’être Dr. Adam B. Lowther Dr. John F. Farrell Departments 103 ❙ Views The Importance of Airpower in Supporting Irregular Warfare in Afghanistan ....................................... 103 Col Bernie Willi, USAF Whither the Leading Expeditionary Western Air Powers in the Twenty-First Century? .................................. 118 Group Capt Tim D. Q. Below, Royal Air Force Exchanging Business Cards: The Impact of the National Defense Authorization Act of 2012 on Domestic Disaster Response ........ 124 Col John L. Conway III, USAF, Retired 129 ❙ Historical Highlight Air Officer’s Education Captain Robert O’Brien 149 ❙ Ricochets & Replies 161 ❙ Book Reviews Stopping Mass Killings in Africa: Genocide, Airpower, and Intervention . .161 Douglas C. Peifer, PhD, ed. Reviewer: 2d Lt Morgan Bennett Truth, Lies, and O-Rings: Inside the Space Shuttle Challenger Disaster . 164 Allan J. McDonald with James R. Hansen Reviewer: Mel Staffeld Allies against the Rising Sun: The United States, the British Nations, and the Defeat of Imperial Japan . 165 Nicholas Evan Sarantakes Reviewer: Lt Col John L. Minney, Alabama Air National Guard Rivals: How the Power Struggle between China, India, and Japan Will Shape Our Next Decade . -

88Rising’ and Their Youtube Approach to Combine Asian Culture with the West

A Study of ‘88rising’ and their YouTube Approach to Combine Asian Culture with the West Haoran Zhang A research Paper submitted to the University of Dublin, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Interactive Digital Media 2018 Declaration I have read, and I understand the plagiarism provisions in the General Regulations of the University Calendar for the current year, found at http://www.tcd.ie/calendar. I have also completed the Online Tutorial on avoiding plagiarism ‘Ready, Steady, Write’, located at http://tcdie.libguides.com/plagiarism/ready- steady-write. I declare that the work described in this Research Paper is, except where otherwise stated, entirely my own work and has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university. Signed: ___________________ Haoran Zhang 08/05/2018 Permission to lend and/or copy I agree that Trinity College Library may lend or copy this research Paper upon request. Signed: ___________________ Haoran Zhang 08/05/2018 Acknowledgements I wish to thank my family and friends, especially my girlfriend Shuyu Zhang for providing me with unfailing support and continuous encouragement throughout my years of study and through the process of researching. I would also like to thank my supervisor Jack Cawley for his patience and guidance during the researching process. Abstract 88rising, as a fledgling new media company based in the USA, has been trying to connect Asian youth culture with the west through its musical and cultural content published on the YouTube channel for the last three years. It is a record label for Asian artists and also a hybrid management company which not only covers music, art, fashion and culture but also creates a hybrid culture of their own.