Domestic Politics, Uncertainty, and Cooperation Between Adversaries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Us Military Assistance to Saudi Arabia, 1942-1964

DANCE OF SWORDS: U.S. MILITARY ASSISTANCE TO SAUDI ARABIA, 1942-1964 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Bruce R. Nardulli, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2002 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Allan R. Millett, Adviser Professor Peter L. Hahn _______________________ Adviser Professor David Stebenne History Graduate Program UMI Number: 3081949 ________________________________________________________ UMI Microform 3081949 Copyright 2003 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ____________________________________________________________ ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road PO Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 ABSTRACT The United States and Saudi Arabia have a long and complex history of security relations. These relations evolved under conditions in which both countries understood and valued the need for cooperation, but also were aware of its limits and the dangers of too close a partnership. U.S. security dealings with Saudi Arabia are an extreme, perhaps unique, case of how security ties unfolded under conditions in which sensitivities to those ties were always a central —oftentimes dominating—consideration. This was especially true in the most delicate area of military assistance. Distinct patterns of behavior by the two countries emerged as a result, patterns that continue to this day. This dissertation examines the first twenty years of the U.S.-Saudi military assistance relationship. It seeks to identify the principal factors responsible for how and why the military assistance process evolved as it did, focusing on the objectives and constraints of both U.S. -

Russia-US Power Struggle for Unpredictable Central Asia

Russia-US power struggle for unpredictable Central Asia Nikola Ostianová Abstract: Th e article focuses on a struggle between the Russian Federation and the US for Central Asian countries states — Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. Th e time settings of the topic encompass period between the collapse of the So- viet Union and the year 2011. Th e paper focuses on a development of a politico-military dimension of the relation between the two Cold War adversaries and Central Asia. It is divided into six parts which deal cover milestone events and issues which infl uenced the dynamics of the competition of Russia and the US in Central Asia. It is concluded that despite of the active engagement of Russia and the US neither of them has been able to gain loyalty of Central Asian countries. Keywords: Central Asia, Russia, the US, military base, security, struggle Introduction A struggle of the Russian Federation and the United States for independent coun- tries in Central Asia — a new Great Game1 — has sparkled after the end of the Cold War. Th e rivalry is characterised by Russia’s eff orts to maintain the infl uence on its former Soviet satellite states — Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan — and the US interest in building yet another of its power bases — this time in the Central Asian region. Th e main goal of the article is to analyse this struggle of Russia and the US in Central Asia with a focus on the politico-military Contemporary European Studies 1/2016 Articles 45 dimension in the timeframe which takes into consideration a period from the end of the Cold War until 2011. -

TPP-2014-08-Power Struggle

20 INTERNATIONAL PARKING INSTITUTE | AUGUST 2014 POWER STRUGGLE Charger squatting is coming to a space near you. Are you ready? By Kim Fernandez HAPPENS ALL THE TIME: Driving down the road, you glance at your fuel gauge to see it’s nearly empty. You pull into the gas station, line up behind IT the car at the pump, and see there’s nobody there actually pumping gas. Maybe that driver is in the convenience store or the restroom or off wandering the neighborhood—who knows? But they’re not refueling; they are blocking the pump, heaven only knows how long they’ll be gone, and you still need gas. Frustrating? You bet. Now transfer that scenario to a parking garage or lot, swap out your SUV for a Nissan Leaf, and picture that gas pump as an electric vehicle (EV) charger that’s blocked by a car that’s not charging. The owner could come back in an hour or a day. There’s no way to tell. But it’s the only charger in the facility, and you need it. DREAMSTIME / HEMERA / BONOTOM STUDIO / HEMERA BONOTOM DREAMSTIME The City of Santa Monica installed signage on its EV charging stations with time limits and other regulations. FRANK CHING Parking a non-charging car at a charger for hours or As EVs become more popular, squatting grows as an days is called “charger squatting,” and the resulting anger issue. Those who’ve already dealt with it say it’s still fairly that builds up in a driver who needs it has been christened new ground, but there are some ways to discourage parking “charger rage.” Both are growing problems that will affect at chargers when a vehicle isn’t actively charging, without parking professionals if they haven’t already. -

Air & Space Power Journal, July-August 2012, Volume 26, No. 4

July–August 2012 Volume 26, No. 4 AFRP 10-1 International Feature Embracing the Moon in the Sky or Fishing the Moon in the Water? ❙ 4 Some Thoughts on Military Deterrence: Its Effectiveness and Limitations Sr Col Xu Weidi, Research Fellow, Institute for Strategic Studies, National Defense University, People’s Liberation Army, China Features Toward a Superior Promotion System ❙ 24 Maj Kyle Byard, USAF, Retired Ben Malisow Col Martin E. B. France, USAF KWar ❙ 45 Cyber and Epistemological Warfare—Winning the Knowledge War by Rethinking Command and Control Mark Ashley From the Air ❙ 61 Rediscovering Our Raison D’être Dr. Adam B. Lowther Dr. John F. Farrell Departments 103 ❙ Views The Importance of Airpower in Supporting Irregular Warfare in Afghanistan ....................................... 103 Col Bernie Willi, USAF Whither the Leading Expeditionary Western Air Powers in the Twenty-First Century? .................................. 118 Group Capt Tim D. Q. Below, Royal Air Force Exchanging Business Cards: The Impact of the National Defense Authorization Act of 2012 on Domestic Disaster Response ........ 124 Col John L. Conway III, USAF, Retired 129 ❙ Historical Highlight Air Officer’s Education Captain Robert O’Brien 149 ❙ Ricochets & Replies 161 ❙ Book Reviews Stopping Mass Killings in Africa: Genocide, Airpower, and Intervention . .161 Douglas C. Peifer, PhD, ed. Reviewer: 2d Lt Morgan Bennett Truth, Lies, and O-Rings: Inside the Space Shuttle Challenger Disaster . 164 Allan J. McDonald with James R. Hansen Reviewer: Mel Staffeld Allies against the Rising Sun: The United States, the British Nations, and the Defeat of Imperial Japan . 165 Nicholas Evan Sarantakes Reviewer: Lt Col John L. Minney, Alabama Air National Guard Rivals: How the Power Struggle between China, India, and Japan Will Shape Our Next Decade . -

The Top 365 Wrestlers of 2019 Is Aj Styles the Best

THE TOP 365 WRESTLERS IS AJ STYLES THE BEST OF 2019 WRESTLER OF THE DECADE? JANUARY 2020 + + INDY INVASION BIG LEAGUES REPORT ISSUE 13 / PRINTED: 12.99$ / DIGITAL: FREE TOO SWEET MAGAZINE ISSUE 13 Mohammad Faizan Founder & Editor in Chief _____________________________________ SENIOR WRITERS.............Nick Whitworth ..........................................Tom Yamamoto ......................................Santos Esquivel Jr SPECIAL CONTRIBUTOR....…Chuck Mambo CONTRIBUTING WRITERS........Matt Taylor ..............................................Antonio Suca ..................................................7_year_ish ARTIST………………………..…ANT_CLEMS_ART PHOTOGRAPHERS………………...…MGM FOTO .........................................Pw_photo2mass ......................................art1029njpwphoto ..................................................dasion_sun ............................................Dragon000stop ............................................@morgunshow ...............................................photosneffect ...........................................jeremybelinfante Content Pg.6……………….……...….TSM 100 Pg.28.………….DECADE AWARDS Pg.29.……………..INDY INVASION Pg.32…………..THE BIG LEAGUES THE THOUGHTS EXPRESSED IN THE MAGAZINE IS OF THE EDITOR, WRITERS, WRESTLERS & ADVERTISERS. THE MAGAZINE IS NOT RELATED TO IT. ANYTHING IN THIS MAGAZINE SHOULD NOT BE REPRODUCED OR COPIED. TSM / SEPT 2019 / 2 TOO SWEET MAGAZINE ISSUE 13 First of all I’ll like to praise the PWI for putting up a 500 list every year, I mean it’s a lot of work. Our team -

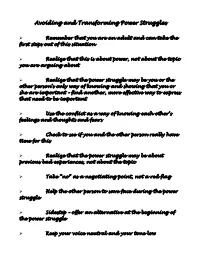

Avoiding and Transforming Power Struggles

Avoiding and Transforming Power Struggles Ø Remember that you are an adult and can take the first steps out of this situation Ø Realize that this is about power, not about the topic you are arguing about Ø Realize that the power struggle may be you or the other person’s only way of knowing and showing that you or she are important – find another, more effective way to express that need to be important Ø Use the conflict as a way of knowing each other’s feelings and thoughts and fears Ø Check to see if you and the other person really have time for this Ø Realize that the power struggle may be about previous bad experiences, not about the topic Ø Take “no” as a negotiating point, not a red flag Ø Help the other person to save face during the power struggle Ø Sidestep – offer an alternative at the beginning of the power struggle Ø Keep your voice neutral and your tone low Ø Avoid known trigger topics during the power struggle Ø You don’t always have to win – accept that and move on Ø Let others have the last word Ø Use conflict and negotiation skills – get training in these Ø Move away from the audience – don’t let your kids see you engaged in a power struggle Ø Sit down – make your body lower than the other person’s – it will diffuse the tension Ø Don’t get drawn into one if either of you is tired Ø Listen to the other person Ø Don’t moralize, sermonize, or use put downs Ø Listen to yourself, monitor your own behaviour Ø Ask the other person for ideas on how to resolve the problem Ø As soon as the other person moves the slightest bit toward compromise, you do the same Brenda McCreight Ph.D. -

Student Government Embroiled in Power Struggle Student Senate

Student government embroiled in power struggle OREXEl INSTTTUTt OF TECHNOICXJY PHILADEIPHIA, PA. VOLUME XLIV FRIDAY, JANUARY 13, 1967 NUMBER 1 Student Senate retains power over rebellious Class Council student Senate retained its role tion by David Furniss (EE ’67) Class Council expenditures. of financial domination over to delete from Senate’s consti By a vote of 3-27-3, Senate Class Council in defeating a mo tution the power to review all elected to retain this power at PENCIL IN HAND, Tony Piersanti makes constitutional objection its January 5 meeting, at which to point Furniss withdrew his re Council actions mode under leadership of Ho Corbin (inset). maining motions related to Class Council’s having to report to Stu dent Senate. Council goes its own way, Furniss defends Council Furniss moved that Art, IV, Sec. 1, No. 7 of the Senate’s appoints Senior successor constitution be deleted. The rul ing states that Senate has the The Class Council, maintain muddy the waters of the debate.” power “ to approve or disapprove ing its position that it is free The letter of resignation was not all expenditures of the classes to interpret its constitution in accepted by the Class Council through the approval of the Class the way it feels is correct un since in fact the proceedings Council budget.” less specifically vetoed by the before the body had declared him Furniss argued that no other Student Senate, proceeded at its im p e a c h e d . organization is required to sub- meeting last Tuesday to appoint Up until the point of his re mit its budget to the Senate be- a successor to the post left va signation, Tedesco considered Text of Tedesco’s letter — cant by the Council’s impeach his impeachment invalid because ment of John Tedesco (C&E 67) See page 14. -

Between Families Foster Parent Retreats Avoiding Power Struggles in Foster Care Power Struggles Do Not Discriminate

IN THIS ISSUE: Foster Family Matters Recruitment Moment Care Provider of the Month Foster Parent Anniversaries July 2014 Foster Family Living Between Families Foster Parent Retreats Avoiding Power Struggles in Foster Care Power struggles do not discriminate. No matter what type anxiety, neglect and apprehension which foster of parent you are – single, married, adoptive or foster, no children experience. It is vital to a foster child’s success one is immune. All parents, at one time or another, have and healthy development for a foster parent to address been sucked into a tug-of-war struggle; both sides wanting these feelings and be a consistent, loving support as the to “win” the war. Power struggles for foster parents can be child works through the residual effects of a chaotic past. especially difficult since a foster child can often state, “I Most power struggles happen after a stressful event when don’t have to listen to you; you’re not my real mom (or the child becomes focused on what he wants and proving that dad).” Foster children often struggle with trust issues and he is right. In turn, parents can become focused on winning need to feel have to control whatever they can. Gaining the argument. When you realize that you are in a power control over situations is done in an effort to not feel struggle, recognize it and take steps to get out of it. Here are completely powerless. some suggestions to avoid or get out of a power struggle: On any given day in the United States, there are more than • Remove yourself from the situation; don’t allow yourself 500,000 children in foster care. -

SPIRITUAL WARFARE Power Struggle Series - Part 1 Ben Rudolph

SPIRITUAL WARFARE Power Struggle Series - Part 1 Ben Rudolph Good morning Life Fellowship. It is so good to be with you here this morning. Last October, which feels like a decade ago, our staff met together for a staff retreat in order to make plans for 2020. We had all these plans and ideas, and one of the things we did was we broke up into three different teams. And each team came up with some things we thought our church needed to hear from God, because we are a church that ultimately wants to hear from God through His Word. We prayed and we talked and we shared ideas of what we thought our church needed for 2020 in our teaching series. And every group said they thought we needed to study spiritual warfare. Every staff member and every pastor in our church felt that they sensed something, and they saw things that were happening, and felt that we needed to understand as a church that we are at war. And we need to understand that there are things happening all around us. Maybe you can sense it. Maybe you have noticed that when you try to do something right that there seems to be something standing in your way, that there seems to be opposition and oppression. So one of the things that we want to do with this series is to become aware of the spiritual warfare that is happening in us and around us. Eugene Peterson said this: “The basic nature of history is warfare.” And that is not just nation against nation. -

Sermon Transcript

SPIRITUAL STRONGHOLDS Power Struggle Series - Part 4 Ben Rudolph Good morning Life Fellowship. It is good to see you here this morning. Turn in your Bibles to II Corinthians Chapter 10 where we are going to be this morning. I hope that you have been enjoying this series. For the last two weeks Pastor Dan has just done an amazing job. He talked about the power over sin two weeks ago and then last week the power over schemes as we have been looking in this series on spiritual warfare. We need to realize that as we live our lives we don’t just live in the material world, we don’t just live our lives freely walking with God, but we need to understand that there is an enemy that attacks us every moment of every day. One of the reasons why we were doing this series is so that we will be aware of how the enemy works. But even more so is the reason that we can have faith in what God is doing in spite of the enemy’s attacks. Part of this series is not so that we look upon the darkness of spiritual forces, and that we get scared and we retreat; the point of this is to understand what the enemy wants to do, how he is working and how he is active, and then understand how God is working in greater ways over the enemy of darkness. Amen? (Amen.) So that is why we are studying this. One of the fears of studying spiritual warfare is that we can get so caught up in looking at what the enemy is doing we fail to look at what God is doing. -

Power Sharing

Chap 3.1 : Power Sharing www.rava.org.in CBSE BOARD Objective Questions Exam 2019-2020 CLASS : 10th SUB : Social Science Unit 4 : Democtracis Politics - II For 15 Years Exams Chapter-wise Question Bank CCHAPTERHAPTER 33.1.1 visit www.cbse.online or whatsapp at 8905629969 Power Sharing 1. OBJECTIVE QUESTIONS Ans : (b) Civil war 10. Belgium has worked on the principles of: 1. Which one of the following countries does not share its (a) majoritarianism (b) accommodation boundary with Belgium? (c) both (a) and (b) (d) none of the above (a) France (b) Netherlands Ans : (b) accommodation (c) Sweden (d) Luxembourg Ans : (c) Sweden 11. Sri Lanka is an island nation, just a few kilometres from the Southern coast of 2. In Belgium, the percentage of French community is: (a) Goa (b) Kerala (a) 54% (b) 40% (c) Tamil Nadu (d) Lakshadweep (c) 30% (d) 20% Ans : (c) Tamil Nadu Ans : (b) 40% NO NEED TO PURCHASE ANY BOOKS 3. Which language is dominantly spoken in Belgium? For session 2019-2020 free pdf will be available at (a) Dutch (b) Spanish www.cbse.online for (c) France (d) Italian 1. Previous 15 Years Exams Chapter-wise Question Ans : (a) Dutch Bank 2. Previous Ten Years Exam Paper (Paper-wise). 4. Power struggle demanding separate Eelam was 3. 20 Model Paper (All Solved). launched by: 4. NCERT Solutions (a) Sinhalese (b) Buddhists All material will be solved and free pdf. It will be (c) Tamilians (d) none of these provided by 30 September and will be updated regularly. Ans : (c) Tamilians 12. -

Power Struggle Customers, Companies, and the Internet of Things by BRENNA SNIDERMAN and MICHAEL E

ISSUE 17 | 2015 Complimentary article reprint Power struggle Customers, companies, and the Internet of Things BY BRENNA SNIDERMAN AND MICHAEL E. RAYNOR > ILLUSTRATION BY ALEX NABAUM About Deloitte Deloitte refers to one or more of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited, a UK private company limited by guarantee (“DTTL”), its network of member firms, and their related entities. DTTL and each of its member firms are legally separate and independent entities. DTTL (also referred to as “Deloitte Global”) does not provide services to clients. Please see www. deloitte.com/about for a more detailed description of DTTL and its member firms. Deloitte provides audit, tax, consulting, and financial advisory services to public and private clients spanning multiple industries. With a globally connected network of member firms in more than 150 countries and territories, Deloitte brings world-class capabilities and high-quality service to clients, delivering the insights they need to address their most complex business challenges. Deloitte’s more than 200,000 professionals are committed to becoming the standard of excellence. This communication contains general information only, and none of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited, its member firms, or their related entities (collectively, the “Deloitte Network”) is, by means of this communication, rendering professional advice or services. No entity in the Deloitte network shall be responsible for any loss whatsoever sustained by any person who relies on this communication. © 2015. For information, contact Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited. 84 Deloitte Review | DELOITTEREVIEW.COM POWER STRUGGLE 85 Power struggle Customers, companies, and the Internet of Things BY BRENNA SNIDERMAN AND MICHAEL E. RAYNOR > ILLUSTRATION BY ALEX NABAUM s the Internet of Things (IoT) permeates people’s daily lives, potentially useful information can now be created every time someone adjusts a thermostat or turns an ignition key or pedals a home-gym exercise bike.