Mapping Partition: the Cartographic Construction of Pakistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Freedom in West Bengal Revised

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchArchive at Victoria University of Wellington Freedom and its Enemies: Politics of Transition in West Bengal, 1947-1949 * Sekhar Bandyopadhyay Victoria University of Wellington I The fiftieth anniversary of Indian independence became an occasion for the publication of a huge body of literature on post-colonial India. Understandably, the discussion of 1947 in this literature is largely focussed on Partition—its memories and its long-term effects on the nation. 1 Earlier studies on Partition looked at the ‘event’ as a part of the grand narrative of the formation of two nation-states in the subcontinent; but in recent times the historians’ gaze has shifted to what Gyanendra Pandey has described as ‘a history of the lives and experiences of the people who lived through that time’. 2 So far as Bengal is concerned, such experiences have been analysed in two subsets, i.e., the experience of the borderland, and the experience of the refugees. As the surgical knife of Sir Cyril Ratcliffe was hastily and erratically drawn across Bengal, it created an international boundary that was seriously flawed and which brutally disrupted the life and livelihood of hundreds of thousands of Bengalis, many of whom suddenly found themselves living in what they conceived of as ‘enemy’ territory. Even those who ended up on the ‘right’ side of the border, like the Hindus in Murshidabad and Nadia, were apprehensive that they might be sacrificed and exchanged for the Hindus in Khulna who were caught up on the wrong side and vehemently demanded to cross over. -

The False Premise of Partition

This article was downloaded by: [Reece Jones] On: 18 August 2014, At: 16:30 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Space and Polity Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cspp20 The false premise of partition Reece Jonesa a Department of Geography, University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, 2424 Maile Way, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA Published online: 12 Aug 2014. To cite this article: Reece Jones (2014): The false premise of partition, Space and Polity, DOI: 10.1080/13562576.2014.932154 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13562576.2014.932154 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

Two Nation Theory: Its Importance and Perspectives by Muslims Leaders

Two Nation Theory: Its Importance and Perspectives by Muslims Leaders Nation The word “NATION” is derived from Latin route “NATUS” of “NATIO” which means “Birth” of “Born”. Therefore, Nation implies homogeneous population of the people who are organized and blood-related. Today the word NATION is used in a wider sense. A Nation is a body of people who see part at least of their identity in terms of a single communal identity with some considerable historical continuity of union, with major elements of common culture, and with a sense of geographical location at least for a good part of those who make up the nation. We can define nation as a people who have some common attributes of race, language, religion or culture and united and organized by the state and by common sentiments and aspiration. A nation becomes so only when it has a spirit or feeling of nationality. A nation is a culturally homogeneous social group, and a politically free unit of the people, fully conscious of its psychic life and expression in a tenacious way. Nationality Mazzini said: “Every people has its special mission and that mission constitutes its nationality”. Nation and Nationality differ in their meaning although they were used interchangeably. A nation is a people having a sense of oneness among them and who are politically independent. In the case of nationality it implies a psychological feeling of unity among a people, but also sense of oneness among them. The sense of unity might be an account, of the people having common history and culture. -

Social Transformation of Pakistan Under Urdu Language

Social Transformations in Contemporary Society, 2021 (9) ISSN 2345-0126 (online) SOCIAL TRANSFORMATION OF PAKISTAN UNDER URDU LANGUAGE Dr. Sohaib Mukhtar Bahria University, Pakistan [email protected] Abstract Urdu is the national language of Pakistan under article 251 of the Constitution of Pakistan 1973. Urdu language is the first brick upon which whole building of Pakistan is built. In pronunciation both Hindi in India and Urdu in Pakistan are same but in script Indian choose their religious writing style Sanskrit also called Devanagari as Muslims of Pakistan choose Arabic script for writing Urdu language. Urdu language is based on two nation theory which is the basis of the creation of Pakistan. There are two nations in Indian Sub-continent (i) Hindu, and (ii) Muslims therefore Muslims of Indian sub- continent chanted for separate Muslim Land Pakistan in Indian sub-continent thus struggled for achieving separate homeland Pakistan where Muslims can freely practice their religious duties which is not possible in a country where non-Muslims are in majority thus Urdu which is derived from Arabic, Persian, and Turkish declared the national language of Pakistan as official language is still English thus steps are required to be taken at Government level to make Urdu as official language of Pakistan. There are various local languages of Pakistan mainly: Punjabi, Sindhi, Pashto, Balochi, Kashmiri, Balti and it is fundamental right of all citizens of Pakistan under article 28 of the Constitution of Pakistan 1973 to protect, preserve, and promote their local languages and local culture but the national language of Pakistan is Urdu according to article 251 of the Constitution of Pakistan 1973. -

The Aaj Ka Dhamaka Edition November 1, 2014

MONSOON The Aaj Ka Dhamaka Edition November 1, 2014 00000 MONSOON ISSUE 1 OUR SPONSORS Carolina Asia Center with the support of the U.S. Department of Edu- cation Center for Global Initiatives UNC Sangam YFund through the Campus Y OUR TEAM Editors: Anisha Padma and Parth Shah Writers: Snigdha Das, Debanjali Kundu, Alekhya Mallavarapu, Dinesh McCoy, Pranati Panuganti, Hinal Patel, Maitreyee Singh, Nikhil Umesh, Soumya Vishwanath, and Naintara Viswanath Photographers: Hamid Ali, Amanda Betner, Arpan Bhandari, Snigdha Das, Aribah Shah, Megha Singh, and Soumya Vishwanath Website Design: Sara Khan Publicity: Ranjitha Ananthan and Iti Madan Magazine Design: Sara Khan and Shruti Patel Contributors: Andrew Ashley, Kane Borders, Mr. John Caldwell, Sarvani Gandhavadi, Dr. Iqbal Sevea, and Dr. Afroz Taj 1 LETTER FROM THE EDITORS Social media has sparked a renaissance of new ideas. Facebook news feeds and Twitter timelines are constantly flooded with photos, videos and articles concerning both local and global issues. UNC Monsoon aims to ride this wave and produce marketable online and print content that brings South Asian voices to the forefront. Prior to Monsoon, UNC Sangam sponsored Diaspora, a campus magazine devoted to South Asian affairs. However, we felt that Diaspora was in need of a rebranding in its mission and name. Monsoon’s mission is to creatively foster dialogue about all eight South Asian countries: Ban- gladesh, India, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Nepal, Maldives, Afghanistan, and Bhutan. It seeks to fight both the misrepresentation and underrepresentation of South Asia in mainstream media by producing original content that informs, entertains, and also fosters discussion. The problem UNC Monsoon addresses is the symbolic annihilation of South Asians by the mainstream media. -

01720Joya Chatterji the Spoil

This page intentionally left blank The Spoils of Partition The partition of India in 1947 was a seminal event of the twentieth century. Much has been written about the Punjab and the creation of West Pakistan; by contrast, little is known about the partition of Bengal. This remarkable book by an acknowledged expert on the subject assesses partition’s huge social, economic and political consequences. Using previously unexplored sources, the book shows how and why the borders were redrawn, as well as how the creation of new nation states led to unprecedented upheavals, massive shifts in population and wholly unexpected transformations of the political landscape in both Bengal and India. The book also reveals how the spoils of partition, which the Congress in Bengal had expected from the new boundaries, were squan- dered over the twenty years which followed. This is an original and challenging work with findings that change our understanding of parti- tion and its consequences for the history of the sub-continent. JOYA CHATTERJI, until recently Reader in International History at the London School of Economics, is Lecturer in the History of Modern South Asia at Cambridge, Fellow of Trinity College, and Visiting Fellow at the LSE. She is the author of Bengal Divided: Hindu Communalism and Partition (1994). Cambridge Studies in Indian History and Society 15 Editorial board C. A. BAYLY Vere Harmsworth Professor of Imperial and Naval History, University of Cambridge, and Fellow of St Catharine’s College RAJNARAYAN CHANDAVARKAR Late Director of the Centre of South Asian Studies, Reader in the History and Politics of South Asia, and Fellow of Trinity College GORDON JOHNSON President of Wolfson College, and Director, Centre of South Asian Studies, University of Cambridge Cambridge Studies in Indian History and Society publishes monographs on the history and anthropology of modern India. -

Http//:Daathvoyagejournal.Com Editor: Saikat Banerjee Department Of

http//:daathvoyagejournal.com Editor: Saikat Banerjee Department of English Dr. K.N. Modi University, Newai, Rajasthan, India. : An International Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies in English ISSN 2455-7544 www.daathvoyagejournal.com Vol.1, No.3, September, 2016 Exploring the Illusive Borderlines: Construction of Identity in the Indian Subcontinent Raj Raj Mukhopadhyay Student, M.A. (II) Department of English VisvaBharati University Email: [email protected] Abstract: The creation of borderlines demarcating the geographical boundary of the state has always problematized the discourse of nation incorporating the issues and debates of race, class, religion and historical events. It is also significant how it presents the ongoing process of the construction of personal ‘identity’ and the cultural determination of one’s selfhood. In the Indian subcontinent, the case is more interesting and complex as nation building takes place in heterogeneous, even fragmented lingual and cultural societies all over our country. The idea of ‘nation’ in the Subcontinent is much complicated, where the question of ethnicity and other forms of religious and political identities play a key role. My paper entitled “Exploring the Illusive Borderlines: Construction of Identity in the Indian Subcontinent” is a very modest attempt to get a glimpse into how the formation of borderlines by the partition of India delineates the construction of racial, religious and cultural ‘identity’ of an individual. This paper aims at studying few short stories like Intizar Husain’s “An Unwritten Epic”, SaadatHasanManto’s “Toba Tek Singh” and films like Vol.1, Issue 3, 2016 Page 67 : An International Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies in English ISSN 2455-7544 www.daathvoyagejournal.com Vol.1, No.3, September, 2016 SrijitMukherji’s “Rajkahini”, Deepa Mehta’s “Earth”, exploring the inherent complexities that arise while defining one’s identity, which is determined by one’s socio-cultural and religious position. -

Copyright by Mohammad Raisur Rahman 2008

Copyright by Mohammad Raisur Rahman 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Mohammad Raisur Rahman certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Islam, Modernity, and Educated Muslims: A History of Qasbahs in Colonial India Committee: _____________________________________ Gail Minault, Supervisor _____________________________________ Cynthia M. Talbot _____________________________________ Denise A. Spellberg _____________________________________ Michael H. Fisher _____________________________________ Syed Akbar Hyder Islam, Modernity, and Educated Muslims: A History of Qasbahs in Colonial India by Mohammad Raisur Rahman, B.A. Honors; M.A.; M.Phil. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2008 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to the fond memories of my parents, Najma Bano and Azizur Rahman, and to Kulsum Acknowledgements Many people have assisted me in the completion of this project. This work could not have taken its current shape in the absence of their contributions. I thank them all. First and foremost, I owe my greatest debt of gratitude to my advisor Gail Minault for her guidance and assistance. I am grateful for her useful comments, sharp criticisms, and invaluable suggestions on the earlier drafts, and for her constant encouragement, support, and generous time throughout my doctoral work. I must add that it was her path breaking scholarship in South Asian Islam that inspired me to come to Austin, Texas all the way from New Delhi, India. While it brought me an opportunity to work under her supervision, I benefited myself further at the prospect of working with some of the finest scholars and excellent human beings I have ever known. -

Index More Information

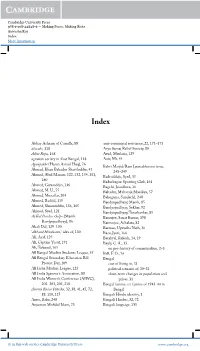

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42828-6 — Making Peace, Making Riots Anwesha Roy Index More Information Index 271 Index Abhay Ashram of Comilla, 88 anti-communal resistance, 22, 171–175 abwabs, 118 Arya Samaj Relief Society, 80 Adim Ripu, 168 Azad, Maulana, 129 agrarian society in East Bengal, 118 Aziz, Mr, 44 Agunpakhi (Hasan Azizul Huq), 76 Babri Masjid/Ram Janmabhoomi issue, Ahmad, Khan Bahadur Sharifuddin, 41 248–249 Ahmed, Abul Mansur, 122, 132, 134, 151, Badrudduja, Syed, 35 160 Badurbagan Sporting Club, 161 Ahmed, Giyasuddin, 136 Bagchi, Jasodhara, 16 Ahmed, M. U., 75 Bahadur, Maharaja Manikya, 57 Ahmed, Muzaffar, 204 Bahuguna, Sunderlal, 240 Ahmed, Rashid, 119 Bandyopadhyay, Manik, 85 Ahmed, Shamsuddin, 136, 165 Bandyopadhyay, Sekhar, 92 Ahmed, Syed, 121 Bandyopadhyay, Tarashankar, 85 Aj Kal Porshur Golpo (Manik Banerjee, Sanat Kumar, 198 Bandyopadhyay), 86 Bannerjee, Ashalata, 82 Akali Dal, 129–130 Barman, Upendra Nath, 36 ‘Akhand Hindustan,’ idea of, 130 Basu, Jyoti, 166 Ali, Asaf, 129 Batabyal, Rakesh, 14, 19 Ali, Captain Yusuf, 191 Bayly, C. A., 13 Ali, Tafazzal, 165 on pre-history of communalism, 2–3 All Bengal Muslim Students League, 55 Bell, F. O., 76 All Bengal Secondary Education Bill Bengal Protest Day, 109 cost of living in, 31 All India Muslim League, 123 political scenario of, 30–31 All India Spinner’s Association, 88 short-term changes in population and All India Women’s Conference (AIWC), prices, 31 202–203, 205, 218 Bengal famine. see famine of 1943-44 in Amrita Bazar Patrika, 32, 38, 41, 45, 72, Bengal 88, 110, 115 Bengali Hindu identity, 1 Amte, Baba, 240 Bengali Hindus, 32, 72 Anjuman Mofidul Islam, 73 Bengali language, 135 © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42828-6 — Making Peace, Making Riots Anwesha Roy Index More Information 272 Index The Bengali Merchants Association, 56 C. -

The Border, City, Diaspora: the Physical and Imagined Borders of South Asia

The Border, City, Diaspora: The Physical and Imagined Borders of South Asia Prithvi Hirani September 28, 2017 Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the Ph.D. Department of International Politics Aberystwyth University 2017 1 Mandatory Layout of Declaration/Statements Word Count of thesis: 83,328 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Candidate name Prithvi Paurin Hirani Signature: Date 14/02/2018 STATEMENT 1 This thesis is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Where *correction services have been used, the extent and nature of the correction is clearly marked in a footnote(s). Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signature: Date 14/02/2018 [*this refers to the extent to which the text has been corrected by others] STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter- library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signature: Date 14/02/2018 NB: Candidates on whose behalf a bar on access (hard copy) has been approved by the University should use the following version of Statement 2: I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter- library loans after expiry of a bar on access approved by Aberystwyth University. Signature: Date 14/02/2018 2 3 Abstract The tussle between borders, identity, and territory continues to dominate politics in postcolonial South Asia. -

From Antiquary to Social Revolutionary: Syed Ahmad Khan and the Colonial Experience by Shamsur Rahman Faruqi

From Antiquary to Social Revolutionary: Syed Ahmad Khan and the Colonial Experience By Shamsur Rahman Faruqi ItisanhonourtodelivertheAnnualSirSyed Memorial Lecture at Aligarh Muslim University, the institutionwhichshouldstandasSirSyedAhmadKhan’s lastingcontributiontothedevelopmentofamodernIndia. ConsciousthoughIamofthehonour,Iamalsobesetby doubtsandfearsaboutmysuitabilityasarecipientofthat honour.IamnotaspecialistofSyedAhmadKhan’sliterary workandsocialandtheologicalthought,thoughtwhich, incidentally,Iregardasahighpointinthehistoryofideasin Islam.MyinterestinandknowledgeofSyedAhmadKhan’s lifeandworksdonotmuchexceedthelevelofareasonably well-informed student of modern Urdu literature. TheonlyprivilegethatIcanclaimisthatasaboyI waspracticallynurturedonSyedAhmadKhanandAkbar Ilahabadi(1846-1921)whommyfatheradmiredgreatlyand didn’tatallseeanydichotomyinadmiringtwoverynearly diametricallyopposedpersonalities.Andthisreconciliation ofoppositeswasquiteparforthecourseforpeopleof certainIndiangenerations,becauseSyedAhmadKhanand AkbarIlahabaditoogreatlyadmiredeachother.SyedAhmad KhanhadsuccessfullycanvassedforAkbarIlahabadibeing postedtoAligarhsothathecouldfreelyenjoyhisfriend’s company. In 1888, when Akbar Ilahabadi was promoted Sub- JudgeandtransferredtoGhazipur,SyedAhmadKhanwrote himacongratulatorynotesayingthatthoughhewassorry forAkbar(headdressedhimasMunshiAkbarHusainSahib) toleaveAligarh,yethewashappyforaMuslimtobecomea Sub-Judgewithalongprospectofactiveserviceinthe judicial department.1 ThroughouthislifeAkbarIlahabadiwasabittercritic andaverynearlyimplacableenemy,ofSyedAhmadKhan’s -

Bilateral Relations Between India and Pakistan, 1947- 1957

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Apollo THE FINALITY OF PARTITION: BILATERAL RELATIONS BETWEEN INDIA AND PAKISTAN, 1947- 1957 Pallavi Raghavan St. Johns College University of Cambridge This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Faculty of History University of Cambridge September, 2012. 1 This dissertation is the result of my own work, includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration, and falls within the word limit granted by the Board of Graduate Studies, University of Cambridge. Pallavi Raghavan 2 ABSTRACT This dissertation will focus on the history of bilateral relations between India and Pakistan. It looks at how the process of dealing with issues thrown up in the aftermath of partition shaped relations between the two countries. I focus on the debates around the immediate aftermath of partition, evacuee property disputes, border and water disputes, minorities and migration, trade between the two countries, which shaped the canvas in which the India-Pakistan relationship took shape. This is an institution- focussed history to some extent, although I shall also argue that the foreign policy establishments of both countries were also responding to the compulsions of internal politics; and the policies they advocated were also shaped by domestic political positions of the day. In the immediate months and years following partition, the suggestions of a lastingly adversarial relationship were already visible. This could be seen from not only in the eruption of the Kashmir dispute, but also in often bitter wrangling over the division of assets, over water, numerous border disputes, as well as in accusations exchanged over migration of minorities.