Two Argentine Song Sets: a Comparison of Songs by De Rogatis And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Cincinnati

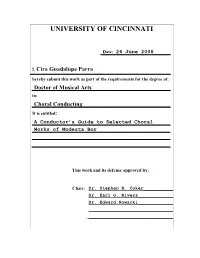

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: 26 June 2006 I, Cira Guadalupe Parra hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Musical Arts in: Choral Conducting It is entitled: A Conductor’s Guide to Selected Choral Works of Modesta Bor This work and its defense approved by: Chair: Dr. Stephen R. Coker___________ Dr. Earl G. Rivers_____________ Dr. Edward Nowacki_____________ _______________________________ _______________________________ A Conductor’s Guide to Selected Choral Works of Modesta Bor A document submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research of the University of Cincinnati In a partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Ensembles and Conducting Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2006 by Cira Parra 620 Clinton Springs Ave Cincinnati, Ohio 45229 [email protected] B.M., University of Cincinnati, College-Conservatory of Music, 1987 M.M., University of Cincinnati, College-Conservatory of Music, 1989 Committee Chair: Stephen R. Coker ABSTRACT Modesta Bor (1926-98) was one of the outstanding Venezuelan composers, conductors, music educators and musicologists of the twentieth century. She wrote music for orchestra, chamber music, piano solo, piano and voice, and incidental music. She also wrote more than 95 choral works for mixed voices and 130 for equal-voice choir. Her style is a mixture of Venezuelan nationalism and folklore with European traits she learned in her studies in Russia. Chapter One contains a historical background of the evolution of Venezuelan art music since the colonial period, beginning in 1770. Knowing the state of art music in Venezuela helps one to understand the unusual nature of the Venezuelan choral movement that developed in the first half of the twentieth century. -

Historical Background

Historical Background Lesson 3 The Historical Influences… How They Arrived in Argentina and Where the Dances’ Popularity is Concentrated Today The Chacarera History: WHAT INFLUENCES MADE THE CHACARERA WHAT IT IS TODAY? HOW DID THESE INFLUENCES MAKE THEIR WAY INTO ARGENTINA? The Chacarera was influenced by the pantomime dances (the Gallarda, the Canario, and the Zarabanda) that were performed in the theaters of Europe (Spain and France) in the 1500s and 1600s. Later, through the Spanish colonization of the Americas, the Chacarera spread from Peru into Argentina during the 1800s (19th century). As a result, the Chacarera was also influenced by the local Indian culture (indigenous people) of the area. Today, it is enjoyed by all social classes, in both rural and urban areas. It has spread throughout the entire country except in the region of Patagonia. Popularity is concentrated in which provinces? It is especially popular in Santiago del Estero, Tucuman, Salta, Jujuy, Catamarca, La Rioja and Cordoba. These provinces are located in the Northwest, Cuyo, and Pampas regions of Argentina. There are many variations of the dance that are influenced by each of the provinces (examples: The Santiaguena, The Tucumana, The Cordobesa) *variations do not change the essence of the dance The Gato History: WHAT INFLUENCES MADE THE GATO WHAT IT IS TODAY? HOW DID THESE INFLUENCES MAKE THEIR WAY INTO ARGENTINA? The Gato was danced in many Central and South American countries including Mexico, Peru, Chile, Uruguay, and Paraguay, however, it gained tremendous popularity in Argentina. The Gato has a very similar historical background as the other playfully mischievous dances (very similar to the Chacarera). -

Lauro Ayestarán, Carlos Vega, Y Las Dos Orillas Del Río De La Plata

Aharonián, Coriún Lauro Ayestarán, Carlos Vega, y las dos orillas del Río de la Plata Revista del Instituto de Investigación Musicológica “Carlos Vega” Año XXVI, Nº 26, 2012 Este documento está disponible en la Biblioteca Digital de la Universidad Católica Argentina, repositorio institucional desarrollado por la Biblioteca Central “San Benito Abad”. Su objetivo es difundir y preservar la producción intelectual de la institución. La Biblioteca posee la autorización del autor para su divulgación en línea. Cómo citar el documento: Aharonián, Coriún. “Lauro Ayestarán, Carlos Vega, y las dos orillas del Río de la Plata” [en línea]. Revista del Instituto de Investigación Musicológica “Carlos Vega” 26,26 (2012). Disponible en: http://bibliotecadigital.uca.edu.ar/repositorio/revistas/ayestaran-vega-dos-orillas-rio.pdf [Fecha de consulta:..........] (Se recomienda indicar fecha de consulta al final de la cita. Ej: [Fecha de consulta: 19 de agosto de 2010]). Revista del Instituto de Investigación Musicológica “Carlos Vega” Año XXVI, Nº 26, Buenos Aires, 2012, pág. 203 LAURO AYESTARÁN, CARLOS VEGA, Y LAS DOS ORILLAS DEL RÍO DE LA PLATA CORIÚN AHARONIÁN Resumen El texto explora el diálogo de las dos figuras fundacionales de la musicología de Argentina y Uruguay: de Vega como maestro y Ayestarán como discípulo, y de ambos como amigos. La rica correspondencia que mantuvieran durante casi tres décadas permite recorrer diversas características de sus personalidades, que se centran obsesivamente en el rigor y en la entrega pero que no excluyen el humor y la ternura. Se aportan observaciones acerca de la compleja relación de ambos con otras personalidades del medio musical argentino. -

The Global Reach of the Fandango in Music, Song and Dance

The Global Reach of the Fandango in Music, Song and Dance The Global Reach of the Fandango in Music, Song and Dance: Spaniards, Indians, Africans and Gypsies Edited by K. Meira Goldberg and Antoni Pizà The Global Reach of the Fandango in Music, Song and Dance: Spaniards, Indians, Africans and Gypsies Edited by K. Meira Goldberg and Antoni Pizà This book first published 2016 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2016 by K. Meira Goldberg, Antoni Pizà and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-9963-1 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-9963-5 Proceedings from the international conference organized and held at THE FOUNDATION FOR IBERIAN MUSIC, The Graduate Center, The City University of New York, on April 17 and 18, 2015 This volume is a revised and translated edition of bilingual conference proceedings published by the Junta de Andalucía, Consejería de Cultura: Centro de Documentación Musical de Andalucía, Música Oral del Sur, vol. 12 (2015). The bilingual proceedings may be accessed here: http://www.centrodedocumentacionmusicaldeandalucia.es/opencms/do cumentacion/revistas/revistas-mos/musica-oral-del-sur-n12.html Frontispiece images: David Durán Barrera, of the group Los Jilguerillos del Huerto, Huetamo, (Michoacán), June 11, 2011. -

Listado De Generos Autorizados.Xls

POR SUBGENERO LISTADO DE GENEROS AUTORIZADOS ACTUALIZADO AL 10 / 10 / 2006 SUBGENERO CODIGO GENERO AFRO 500 INTERNACIONAL AGOGO 594 INTERNACIONAL AIRES ESPAÑOLES 501 INTERNACIONAL ALBORADA 502 INTERNACIONAL ALEGRO VIVACE 455 SINFONICO Y CAMARA ANATEADA 627 FOLKLORE ANDANTE 400 SINFONICO Y CAMARA ARIA 401 SINFONICO Y CAMARA AUQUI AUQUI 633 FOLKLORE BAGUALA 300 FOLKLORE BAILECITO 301 FOLKLORE BAILE 402 INTERNACIONAL BAILES 302 FOLKLORE BAION 503 INTERNACIONAL BALADA 100 MELODICO BALLET 403 SINFONICO Y CAMARA BAMBUCO 595 INTERNACIONAL BARCAROLA 504 INTERNACIONAL BATUCADA 505 INTERNACIONAL BEAT 101 MELODICO BEGUINE 102 MELODICO BERCEUSE 404 SINFONICO Y CAMARA BLUES 103 MELODICO BOCETO 405 SINFONICO Y CAMARA BOGALOO 105 MELODICO BOLERO 104 MELODICO BOMBA 506 INTERNACIONAL BOOGIE BOOGIE 106 MELODICO BOSSA NOVA 507 INTERNACIONAL BOTECITO 508 INTERNACIONAL BULERIAS 509 INTERNACIONAL CACHACA 615 INTERNACIONAL CACHARPAYA 302 FOLKLORE CAJITA DE MUSICA 406 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CALIPSO 107 MELODICO CAMPERA 303 FOLKLORE CAN CAN 510 INTERNACIONAL CANCION 108 MELODICO CANCION DE CUNA 453 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CANCION FOLKLORICA 358 FOLKLORE Página 1 POR SUBGENERO LISTADO DE GENEROS AUTORIZADOS ACTUALIZADO AL 10 / 10 / 2006 SUBGENERO CODIGO GENERO CANCION INDIA 643 FOLKLORE CANCION INFANTIL 407 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CANCION MAPUCHE 642 FOLKLORE CANDOMBE 1 POPULAR CANON 408 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CANTATA 409 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CANTE JONDO 511 INTERNACIONAL CANZONETTA 109 MELODICO CAPRICCIO 410 SINFONICO Y CAMARA CARAMBA 304 FOLKLORE CARNAVAL 348 FOLKLORE CARNAVALITO -

Facultad De Artes Y Diseño TESIS DE MAESTRÍA CINCO

Facultad de Artes y Diseño TESIS DE MAESTRÍA CINCO PROPUESTAS LATINOAMERICANAS DE FLAUTA Y PERCUSIÓN: INTERSECCIÓN ENTRE LO POPULAR Y LO ACADÉMICO CARRERA DE POSGRADO Maestría en Interpretación de Música Latinoamericana del siglo XX Tesista: Virginia Mendez Director: Mgter. Octavio Sánchez Codirectora: Mgter. María Inés García Mendoza, Octubre de 2014. RESUMEN Esta investigación se centra en composiciones para flauta y percusión de compositores latinoamericanos nacidos en la segunda mitad del siglo XX. Dentro de las obras seleccionadas introducen elementos de la música popular de sus países de origen en intersección con la música académica del siglo XX. Este tipo de repertorio no es muy difundido en Argentina y sólo llega a un público muy reducido. La utilización de ciertos tópicos posiciona a las obras como producciones que manifiestan una identidad nacional y una pertenencia a la cultura latinoamericana. Las obras seleccionadas para el Concierto-Tesis pertenecen al repertorio de música de cámara y están presentes una gran variedad de recursos tímbricos y texturales tanto en la percusión como en la flauta. En cuanto a la metodología se realizaron entrevistas a los compositores; recolección y selección de material bibliográfico y partituras; análisis para dilucidar elementos populares; estudio técnico e interpretativo. Los objetivos principales de esta investigación son: Identificar mediante el análisis musical y de tópicos ciertos elementos pertenecientes a una zona de intersección entre los lenguajes populares y académicos. Proponer estrategias en relación al aspecto interpretativo. Poner en valor este repertorio propiciando su circulación mediante la realización de conciertos. 2 AGRADECIMIENTOS Me gustaría que estas líneas sirvieran para expresar mi más profundo y sincero agradecimiento a todas aquellas personas que con su ayuda han colaborado en la realización del presente trabajo. -

Raíces Rojas (Presentación)

RAÍCES ROJAS Libreto de G. Galo Con música, letras e idea original de Camilo David Salas Avila PROCESO CREATIVO • Colectividad • Teatro – Musical (Investigación) • Temática Direccionada (Historia Colonial) • Idea original (Personajes y Suceso angular) • Libreto • Géneros (Referencias) • Canciones (Lead Sheet) / Reducciones • Arreglos (Partituras) • Preproducción • Producción • Posproducción RAICES ROJAS Teatro musical en un acto De: G. Galo con música, letras e idea original de: Camilo D. Salas • Personajes: Nazario Lucena, Militar Español. Celia, Esclava. Talito, Indígena. Hermana Inés (Juana Anastasia), falsa monja y ex-mercader. Tres Cimarronas, Esclavas rebeldes. RAICES ROJAS Teatro musical en un acto De: G. Galo con música, letras e idea original de: Camilo D. Salas • Sinópsis: En algún lugar de la provincia de Cartagena de Indias, en algún momento del siglo XVIII d.C, la antiguamente hermosa hacienda de Nasario Lucena —quien en tiempos de gloria fuera un célebre almirante de la Armada Española y ahora ya venido a menos— guarda entre sus paredes los desesperados esfuerzos de sus tres únicos integrantes que intentan mantener a toda costa sus particulares intereses. Nazario —el español—, Talito — el indígena— y Celia —la esclava—, acostumbrados a vivir en un férrea dependencia y acompañada soledad, se verán obligados a revelar antiguos secretos con la llegada de una peculiar monja a sus vidas que les hará reconocer a cada uno de ellos que el juego de la vida al final solo develará las más dolorosas verdades. CANCIONES Y ARREGLOS 1. La Sangre (Bullerengue Sentao, Chalupa). 2. Como la Tierra al Sol (Danzón, Chachachá, Son). 3. Mi Fuerza (Flamenco). 4. Seguimos Aquí (Tango). 5. -

Música Infancias Visuales Artes Performáticas Talleres Literatura Podcasts Ferias Cine Audiovisual Transmisiones En Vivo Contenidos

Semana del 4 al 7 de marzo de 2021 música infancias visuales artes performáticas talleres literatura podcasts ferias cine audiovisual transmisiones en vivo Contenidos página 04 / Música Autoras Argentinas Porque sí Homenaje a Claudia Montero Música académica en el Salón de Honor Himno Nacional Argentino Nuestrans Canciones: Brotecitos Mujer contra mujer. 30 años después Un mapa 5 Agite musical Infancias 30/ Mujeres y niñas mueven e inventan el mundo Un mapita 35/ Visuales Cuando cambia el mundo. Preguntas sobre arte y feminismos Premio Adquisición Artes Visuales 8M Performáticas 39/ Agite: Performance literaria Presentaciones de libros Archivo vivo: mujeres x mujeres Malambo Bloque Las Ñustas Vengan de a unx Talleres 50/ Nosotres nos movemos bajo la Cruz del Sur Aproximación a la obra de Juana Bignozzi Poesía cuir en tembladeral 54/ Ferias Feria del Libro Feminista Nosotras, artesanas Audiovisual 59/ Cine / Contar Bitácoras Preestrenos Conversatorios Transmisiones en vivo Pensamiento 66/ Conversatorios Podcasts: Alerta que camina Podcasts: Copla Viva 71/ Biografías nosotras movemos el mundo Segunda edición 8M 2021 Mover el mundo, hacerlo andar, detenerlo y darlo vuelta para modifcar el rumbo. Mover el mundo para que se despierte de esta larga pesadilla en la que algunos cuerpos son posesión de otros, algunas vidas valen menos, algunas vidas cuestan más. Hoy, mujeres y diversidades se encuentran en el centro de las luchas sociales, son las más activas, las más fuertes y también las más afectadas por la desposesión, por el maltrato al medioambiente, por la inercia de una sociedad construida a sus espaldas pero también sobre sus hombros. Nosotras movemos al mundo con trabajos no reconocidos, con nuestro tiempo, con el legado invisible de las tareas de cuidado. -

Música. Taller De Audición, Creación E Interpretación Aportes Para La Enseñanza

Nivel Medio Aportes para la enseñanza 2006 Música Taller de audición, creación e intrepretación G. C. B. A. MINISTERIO DE EDUCACIÓN SUBSECRETARÍA DE EDUCACIÓN DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE PLANEAMIENTO DIRECCIÓN DE CURRÍCULA Música Taller de audición, creación e interpretación G.C.B.A. EDIO M VEL NI Aportes para la enseñanza. 2006 Música Taller de audición, creación e interpretación G. C. B. A. MINISTERIO DE EDUCACIÓN SUBSECRETARÍA DE EDUCACIÓN DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE PLANEAMIENTO G.C.B.A. DIRECCIÓN DE CURRÍCULA Música taller de audición, creación e interpretación / ; coordinado por Marcela Benegas - 1a ed. - Buenos Aires : Ministerio de Educación - Gobierno de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires, 2006. 96 p. ; 30x21 cm. (Aportes para la enseñanza nivel medio) ISBN 987-549-304-X 1. Música-Enseñanza. I. Benegas, Marcela, coord. CDD 780.7 Este documento se entrega junto con dos CDs que reúnen obras musicales, partituras y fichas de trabajo. ISBN-10: 987-549-304-X ISBN-13: 978-987-549-304-9 © Gobierno de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires Ministerio de Educación Dirección General de Planeamiento Dirección de Currícula. 2006 Hecho el depósito que marca la Ley nº 11.723 Esmeralda 55. 8º. C1035ABA. Buenos Aires Correo electrónico: [email protected] Permitida la transcripción parcial de los textos incluidos en esta obra, hasta 1.000 palabras, según Ley 11.723, art. 10º, colocando el apartado consultado entre comillas y citando la fuente; si éste excediera la extensión mencionada deberá solicitarse autorización a la Dirección de Currícula. Distribución gratuita. Prohibida su venta. G.C.B.A. GOBIERNO DE LA CIUDAD DE BUENOS AIRES Jefe de Gobierno JORGE TELERMAN Ministro de Educación ALBERTO SILEONI Subsecretaria de Educación MARA BRAWER Director General de Educación EDUARDO ARAGUNDI Director de Área de Educación Media y Técnica HUGO SERENO Directora de Área de Educación Artística BEATRIZ ZETINA Directora General de Planeamiento ANA M. -

Zonceras Folkloricas Argentinas

ZONCERAS FOLKLORICAS ARGENTINAS PARTE I ZAPATEO FLAMENCO omenzaré por el Zapateo Flamenco, podría ser por cualquier otro, porque no somos los inventores de “mover las tabas”; no porque le encuentre algo parecido, solo el golpeteo de los pies sobre el suelo, con cierta habilidad, sino porque los “enseñadores de las Escuelas de Danzas Nativas (?) o de algunas páginas web hacen y dicen cosas sobre el malambo que no tienen nada que ver. No es menos absurdo la explicación que se da sobre el zapateo flamenco, que dicho sea de paso es mucho más coherente con lo que debería ser el malambo, pero dice: 1) que se ejecuta con los pies, ¡¡vaya sabiduría!! usando zapatos de flamenco, ¿y todos los flamencos no usa zapatos? Pero ahí no termina la cosa: dice que en un principio –folklórico quizá-lo bailaban solo los varones, ahora incluye a mujeres ¿no le resulta conocido? No tengo dudas que se ha alterado el folklore español. Un libro poco conocido, o directamente desconocido, se refiere a: “Con una portada para un libro de creación lírica popular, salió este cancionero de coplas de Manuel Pachón Lozano, un poeta del pueblo que nos dejó en él un buen manojo de composiciones, la mayoría de ellas de Soleá, Sevillanas y Fandangos ( )”1 1 -De Mi Torre Cobalto -4 de junio de 2011 -Libros Con Son Flamenco: verdades por Soleares -Sevilla-1979 Ed del autor 1 ......, además, ¿Qué parecidas que son las botas de “nuestros seudo gauchos a las flamencas, noooo?...., ¡¡qué bellos taquitos!!! “En España el zapateado sobrevive gracias a que pasa a integrarse al baile flamenco”. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE the 1964 Festival Of

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE The 1964 Festival of Music of the Americas and Spain: A Critical Examination of Ibero- American Musical Relations in the Context of Cold War Politics A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Alyson Marie Payne September 2012 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Leonora Saavedra, Chairperson Dr. Walter Clark Dr. Rogerio Budasz Copyright by Alyson Marie Payne 2012 The Dissertation of Alyson Marie Payne is approved: ______________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgments I would like to acknowledge the tremendous help of my dissertation committee, Dr. Leonora Saavedra, Dr. Walter Clark, and Dr. Rogerio Budasz. I am also grateful for those that took time to share their first-hand knowledge with me, such as Aurelio de la Vega, Juan Orrego Salas, Pozzi Escot, and Manuel Halffter. I could not have completed this project with the support of my friends and colleagues, especially Dr. Jacky Avila. I am thankful to my husband, Daniel McDonough, who always lent a ready ear. Lastly, I am thankful to my parents, Richard and Phyllis Payne for their unwavering belief in me. iv ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The 1964 Festival of Music of the Americas and Spain: A Critical Examination of Ibero- American Musical Relations in the Context of Cold War Politics by Alyson Marie Payne Doctor of Philosophy, Graduate Program in Music University of California, Riverside, September 2012 Dr. Leonora Saavedra, Chairperson In 1964, the Organization of American States (OAS) and the Institute for Hispanic Culture (ICH) sponsored a lavish music festival in Madrid that showcased the latest avant-garde compositions from the United States, Latin America, and Spain. -

THE INVENTION of the NATIONAL in VENEZUELAN ART MUSIC, 1920-1960 by Pedro Rafael Aponte Licenciatura En Música, Instituto Univ

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by D-Scholarship@Pitt THE INVENTION OF THE NATIONAL IN VENEZUELAN ART MUSIC, 1920-1960 by Pedro Rafael Aponte Licenciatura en Música, Instituto Universitario de Estudios Musicales, 1995 M.M., James Madison University, 1997 M.A., University of Pittsburgh, 2004 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2008 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF MUSIC This dissertation was presented by Pedro Rafael Aponte It was defended on October 27, 2008 and approved by Dr. Deane Root, Professor of Music Dr. Don Franklin, Professor of Music Dr. Mary Lewis, Professor of Music Dr. Joshua Lund, Associate Professor of Hispanic Languages and Literature Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Deane Root, Professor of Music ii Copyright © by Pedro Rafael Aponte 2008 iii THE INVENTION OF THE NATIONAL IN VENEZUELAN ART MUSIC, 1920-1960 Pedro Rafael Aponte, Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh, 2008 This dissertation explores the developments of art music in Venezuela during the first half of the twentieth century as an exercise in nation building. It argues that beginning in the early 1920s a nationalist movement in music emerged, which was not only determined by but also determinant in the construction of a concept of nationhood. The movement took place at a crucial time when the country had entered a process of economic transformation. The shift in Venezuela’s economic system from agrarian to industrial in the 1910s triggered a reconfiguration of the country’s social and cultural structures.