Methods and Practice of First Nations Australian Representation in Young Adult Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Surprised by Joy: Children, Text and Identity

The Seventh Royale Ormsby Martin Lecture 2000 Surprised by Joy: Children, Text and Identity Maurice Saxby The Royale Ormsby Martin Lecture is administered by the Anglican Education Commission, Diocese of Sydney (a division of Anglican Youthworks) on behalf of the trustees: the Archbishop of Sydney, the Dean of Sydney and the Director of Education 1 Maurice Saxby Maurice Saxby, who was trained at Balmain Teacher’s College but went on to complete an Honours Degree in English from Sydney University as an evening student, believes passionately in the power of literature to enhance life, both for children and adults. He has taught infants, primary and secondary school students, but his career has been mainly as a lecturer in tertiary institutions. He retired as Head of the English Department at Kuring-gai College of Advanced Education. He has lectured extensively in children’s literature both in Australia and overseas including England, America, Germany, Japan and China. Maurice was the first National President of the Children’s Book Council of Australia and has served on judging panels for children’s literature many times in Australia; and he is the only Australian to have been selected as a juror for the prestigious international Hans Andersen Awards. He has received the Dromkeen Medal, the Lady Cutler Award and an Order of Australia for his services to children’s literature. Maurice’s publications range from academic works such as Offered to Children: A History of Australian Children’s Literature 1841–1941; Give them Wings: The Experience of Children’s Literature and Teaching Literature to Adolescents. -

Sacs Secondary Reading Lists

Sacs Secondary Reading Lists ST ANDREW’S CATHEDRAL SCHOOL SECONDARY BOOK LISTS Aboriginal stories Action and adventure Biography and autobiography Christian Classics Crime Dystopian Fantasy Graphic novels Historical fiction Humorous stories Love and romance Middle School reading list Multicultural stories Non fiction Science fiction Senior reading list Short stories (online) Sports Thrillers War stories World literature St Andrew’s Cathedral School Secondary Reading Lists 2015 Page 1 ABORIGINAL STORIES Definition: fiction books written by Aboriginal authors. Author Title or Series Behrendt, Larissa Home Coleman, Dylan Mazin Grace Fran, Dobbie Whisper Paper bags and dreams Frankland, Richard J. Walking the boundaries Heiss, Anita Who am I? The diary of Mary Talence, Sydney, 1937 (or any other title) Leane, Jeanine Purple threads Lucashenko, Melissa Killing Darcy McDonald, Meme & My girragundji Prior, Boori The Binna Binna Man Njunjul the sun Mudrooroo (Johnson, Master of the ghost dreaming series Colin) Wild cat falling Norrington, Leonie The Barrumbi kids series Watson, Nicole The boundary Wharton, Herb Yumba days Wimot, Eric Pemulwuy: the Rainbow Warrior St Andrew’s Cathedral School Secondary Reading Lists 2015 Page 2 ABORIGINAL PICTURE BOOKS Definition: junior picture books written by Aboriginal authors. Author Title or Series Adams, Jeanie Going for oysters Pigs and honey Bancroft, Bronwyn Possum & Wattle or any other title Barunga, Albert About this little devil and this little fella Fry, Chris Nardika learns to make a spear Greene, -

Submission to the Productivity Commission Re Copyright Restrictions on the Parallel Importation of Books

SUBMISSION TO THE PRODUCTIVITY COMMISSION RE COPYRIGHT RESTRICTIONS ON THE PARALLEL IMPORTATION OF BOOKS 14 January, 2009 As a peak Australian voluntary organisation whose membership represents authors, illustrators, publishers, booksellers, teachers, librarians, teacher-librarians and parents, the Children's Book Council of Australia would like to express its objection to changes to present provisions of the Copyright Act that restrict parallel importation. Australia has a vibrant book industry, including the publication of many books for children. We see these books as a major enculturating force – they help Australian children to discover and celebrate who we are and what is important to us; they tell us our own unique stories in our own language/s, asking us to critically examine ourselves and our way of life. Every year, in schools around Australia, tens of thousands of Australian children celebrate the best of Australian children's literature, culminating in the CBCA Book of the Year Awards followed by Book Week. Australian award-winning books are written by new as well as established authors. With some of these books, Australian publishers have taken a chance in their publication; a chance which may not have been taken if parallel importation restrictions had been lifted. Australian authors feature prominently in international awards and honour lists because of the high quality of their work. Before succeeding overseas, all of these authors have first been published by Australian publishers. Some (but not all) award- winning Australian -

The Children's Book Council of Australia Book of the Year Awards

THE CHILDREN’S BOOK COUNCIL OF AUSTRALIA BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARDS 1946 — CONTENTS Page BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARDS 1946 — 1981 . 2 BOOK OF THE YEAR: OLDER READERS . .. 7 BOOK OF THE YEAR: YOUNGER READERS . 12 VISUAL ARTS BOARD AWARDS 1974 – 1976 . 17 BEST ILLUSTRATED BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARD . 17 BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARD: EARLY CHILDHOOD . 17 PICTURE BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARD . 20 THE EVE POWNALL AWARD FOR INFORMATION BOOKS . 28 THE CRICHTON AWARD FOR NEW ILLUSTRATOR . 32 CBCA AWARD FOR NEW ILLUSTRATOR . 33 CBCA BOOK WEEK SLOGANS . 34 This publication © Copyright The Children’s Book Council of Australia 2021. www.cbca.org.au Reproduction of information contained in this publication is permitted for education purposes. Edited and typeset by Margaret Hamilton AM. CBCA Book of the Year Awards 1946 - 1 THE CHILDREN’S BOOK COUNCIL OF AUSTRALIA BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARDS 1946 – From 1946 to 1958 the Book of the Year Awards were judged and presented by the Children’s Book Council of New South Wales. In 1959 when the Children’s Book Councils in the various States drew up the Constitution for the CBC of Australia, the judging of this Annual Award became a Federal matter. From 1960 both the Book of the Year and the Picture Book of the Year were judged by the same panel. BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARD 1946 - 1981 Note: Until 1982 there was no division between Older and Younger Readers. 1946 – WINNER REES, Leslie Karrawingi the Emu John Sands Illus. Walter Cunningham COMMENDED No Award 1947 No Award, but judges nominated certain books as ‘the best in their respective sections’ For Very Young Children: MASON, Olive Quippy Illus. -

Pdf Parks Victoria

5 Den of Nargun, Mitchell River National Park by Sharnee Sergi and Ian D. Clark This chapter is concerned to document the history of the development of the Den of Nargun as a tourism site utilising the theoretical constructs developed by MacCan- nell (1976), Butler (1980) and Gunn (1994). These perspectives provide insights into the historical maturation of a cultural or natural site into a tourism attraction. Mac- Cannell’s (1976) perspective reflects progressive development of attractions over five phases – naming, framing and elevation, enshrinement and duplication, and social reproduction. For the purpose of this study, Butler’s (1980) ‘tourism area life cycle model’ will be correlated with MacCannell’s model of the evolution of attractions in order to navigate the development and tourism history of the Den of Nargun. Further- more, utilisation of Gunn’s (1994) spatial model helps to provide an understanding of the contextual and environmental development and character of the site. The Den of Nargun is an important geological and Aboriginal cultural site located in the Mitchell River National Park in East Gippsland and is situated approximately 50km northwest of Bairnsdale, Victoria. The evolution of the Den of Nargun as a tourism attraction is contextualised with the Mitchell River National Park’s own history and will be, in part, explored in this study. The Mitchell River National Park and the Den of Nargun, as it is known today, was formally known as the Glenaladale National Park (Catrice, 1996). References to the Den of Nargun are commonly cited in older works as being a part of the Glenaladale National Park. -

Story Time: Australian Children's Literature

Story Time: Australian Children’s Literature The National Library of Australia in association with the National Centre for Australian Children’s Literature 22 August 2019–09 February 2020 Exhibition Checklist Australia’s First Children’s Book Charlotte Waring Atkinson (Charlotte Barton) (1797–1867) A Mother’s Offering to Her Children: By a Lady Long Resident in New South Wales Sydney: George Evans, Bookseller, 1841 Parliament Collection (Australian Printed) nla.cat-vn777812 Charlotte Waring Atkinson (Charlotte Barton) (1797–1867) A Mother’s Offering to Her Children: By a Lady Long Resident in New South Wales Sydney: George Evans, Bookseller, 1841 Ferguson Collection (Australian Printed) nla.cat-vn777812 Living Knowledge Nora Heysen (1911–2003) Bohrah the Kangaroo 1930 pen, ink and wash Original drawings to illustrate Woggheeguy: Australian Aboriginal Legends, collected and written by Catherine Stow (Pictures) nla.cat-vn1453161 Nora Heysen (1911–2003) Dinewan the Emu 1930 pen, ink and wash Original drawings to illustrate Woggheeguy: Australian Aboriginal Legends, collected and written by Catherine Stow (Pictures) nla.cat-vn1458954 Nora Heysen (1911–2003) They Saw It Being Lifted from the Earth 1930 pen, ink and wash Original drawings to illustrate Woggheeguy: Australian Aboriginal Legends, collected and written by Catherine Stow (Pictures) nla.cat-vn2980282 1 Catherine Stow (K. ‘Katie’ Langloh Parker) (author, 1856–1940) Tommy McRae (illustrator, c.1835–1901) Australian Legendary Tales: Folk-lore of the Noongahburrahs as Told to the Piccaninnies London: David Nutt; Melbourne: Melville, Mullen and Slade, 1896 Ferguson Collection (Australian Printed) nla.cat-vn995076 Catherine Stow (K. ‘Katie’ Langloh Parker) (author, 1856–1940) Henrietta Drake-Brockman (selector and editor, 1901–1968) Elizabeth Durack (illustrator, 1915–2000) Australian Legendary Tales Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1953 Ferguson Collection (Australian Printed) nla.cat-vn2167373 Catherine Stow (K. -

The Children's Book Council of Australia Book Of

THE CHILDREN’S BOOK COUNCIL OF AUSTRALIA BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARDS 1946 – From 1946 to 1958 the Book of the Year Awards were judged and presented by the Children’s Book Council of New South Wales. In 1959 when the Children’s Book Councils in the various States drew up the Constitution for the CBC of Australia, the judging of this Annual Award became a Federal matter. From 1960 both the Book of the Year and the Picture Book of the Year were judged by the same panel. BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARD 1946 - 1981 Note: Until 1982 there was no division between Older and Younger Readers. 1946 – WINNER REES, Leslie Karrawingi the Emu John Sands Illus. Walter Cunningham COMMENDED No Award 1947 No Award, but judges nominated certain books as ‘the best in their respective sections’ For Very Young Children: MASON, Olive Quippy John Sands Illus. Walter Cunninghan Five to Eight Years: MEILLON, Jill The Children’s Garden Australasian Publishing BASSER, Veronica The Glory Bird John Sands Illus. Elaine Haxton Eight to Twelve Years: GRIFFIN, David The Happiness Box Australasian Publishing Illus. Leslie Greener REES, Leslie The Story of Sarli the Turtle John Sands Illus. Walter Cunningham McFADYEN, Ella Pegman’s Tales Angus & Robertson Illus. Edina Bell WILLIAMS, Ruth C. Timothy Tatters Bilson Honey Pty Illus. Rhys Williams Teenage: BIRTLES, Dora Pioneer Shack Shakespeare Head 1948 – WINNER HURLEY, Frank Shackleton's Argonauts Angus & Robertson HIGHLY COMMENDED MARTIN, J.H. & W.D. The Australian Book of Trains Angus & Robertson JACKSON, Ada Beatles Ahoy! Paterson Press Illus. Nina Poynton (chapter headings) MORELL, Musette Bush Cobbers Australasian Publishing Illus. -

Your Reading: a Booklist for Junior High and Middle School Students

ED 337 804 CS 213 064 AUTHOR Nilsen, Aileen Pace, Ed. TITLE Your Reading: A Booklist for JuniOr High and Middle School Students. Eighth Edition. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-5940-0; ISSN-1051-4740 PUB DATE 91 NOTE 347p.y Prepared by the Committee on the Junior High and Middle School Booklist. For the previous edition, see ED 299 570. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 59400-0015; $12.95 members, $16.95 nonmembers). PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC14 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adolescent Literature; Annotated Bibliographies; *Boots; Junior High Schools; Junior High School Students; *Literature Appreciation; Middle Schools; Reading Interests; Reuding Material Selection; Recreational Reading; Student Interests; *Supplementary Reading Materials IDENTIFIERS Middle School Students ABSTRACT This annotated bibliography for junior high and middle school students describes nearly 1,200 recent books to read for pleasure, for school assignments, or to satisfy curiosity. Books included are divided inco six Lajor sections (the first three contain mostly fiction and biographies): Connections, Understandings, Imaginings, Contemporary Poetry and Short Stories, Books to Help with Schoolwork, and Books Just for You. These major sections have been further subdivided into chapters; e.g. (1) Connecting with Ourselves: Accomplishments and Growing Up; (2) Connecting with Families: Close Relationships; (3) -

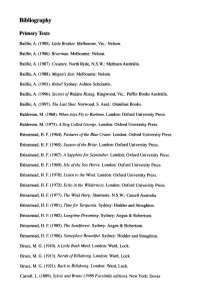

Bibliography Primary Texts

Bibliography Primary Texts Baillie, A. (1985). Little Brother. Melbourne, Vic: Nelson. Baillie, A. (1986). Riverman. Melbourne: Nelson. Baillie, A. (1987). Creature. North Ryde, N.S.W.: Methuen Australia. Baillie, A. (1988). Megan's Star. Melbourne: Nelson. Baillie, A. (1993). Rebel! Sydney: Ashton Scholastic. Baillie, A. (1996). Secrets ofWalden Rising. Ringwood, Vic: Puffin Books Australia. Baillie, A. (1997). The Last Shot. Norwood, S. Aust: Omnibus Books. Balderson, M. (1968). When Jays Fly to Barbmo. London: Oxford University Press. Balderson, M. (1975). A Dog Called George. London: Oxford University Press. Brinsmead, H. F. (1964). Pastures of the Blue Crane. London: Oxford University Press. Brinsmead, H. F. (1965). Season of the Briar. London: Oxford University Press. Brinsmead, H. F. (1967). A Sapphire for September. London: Oxford University Press. Brinsmead, H. F. (1969). Isle of the Sea Horse. London: Oxford University Press. Brinsmead, H. F. (1970). Listen to the Wind. London: Oxford University Press. Brinsmead, H. F. (1972). Echo in the Wilderness. London: Oxford University Press. Brinsmead, H. F. (1977). The Wind Harp. Stanmore, N.S.W.: Cassell Australia. Brinsmead, H. F. (1981). Time for Tarquinia. Sydney: Hodder and Stoughton. Brinsmead, H. F. (1982). Longtime Dreaming. Sydney: Angus & Robertson. Brinsmead, H. F. (1985). The Sandforest. Sydney: Angus & Robertson. Brinsmead, H. F. (1986). Someplace Beautiful. Sydney: Hodder and Stoughton. Bruce, M. G. (1910). A Little Bush Maid. London: Ward, Lock. Bruce, M. G. (1913). Norah ofBillabong. London: Ward, Lock. Bruce, M. G. (1921). Back to Billabong. London: Ward, Lock. Carroll, L. (1889). Sylvie and Bruno (1988 Facsimile edition). New York: Dover Publications, Inc. Chauncy, N. -

SOURCE01.Pdf

t, 5S nlf.. 3, 6, :2-25, ~, 30- ;S, SA AUSTRALIAN FANTASY AND FOLKLORE A Ninya AUSTRALIAN FANTASY AND FOLKLORE by ~l. 8. Ryan .. University of New England Armidale 1981 @ 1981 Copyright is reserved to J.S. Ryan and Joan Phipson respectively ISBN 0 85834 359 2 Printed for the Department of Continuing Education by the P.rinting Unit, University of New England, Armidale, New South Wales INTRODUCTION My qualifications for the privilege of introducing the following survey are that I know no more than the average person about folklore and perhaps less about Aboriginal folklore; about fantasy in general, perhaps a little more than average. Backhanded qualifications perhaps, yet they do allow me to receiye as fresh and new many of the ideas put forward by Professor Ryan and the writers quoted. When I began to write stories for children in the 1950s I was told then, and for some years afterwards, that it was useless to try to write fantasy, that Australian children did not - could not - read fantasy, and in any case, the suggestion was, why waste time on such trifling stuff? I was sorry because I remembered my own intense pleasure in the books of fantasy I had read when young - all the fairy tales that ever were, my favouri tes (pa,~e Hans Andersen) being the bloody-minded brothers Grirrml; but also Alice in Wonderlan,i~ The Water Babies, skipping the exhortations to childish virtue, The Wind 1.:n the willows and many others. If one could write anything remotely resembling these, what a pity to deny children the enormous pleasure of reading it. -

Teaching Classic Literature

Using Children’s Literature in a literacy rich classroom Preamble In a recent address to principals in the South-Western Region, Regional Director, Sharyn Donald reiterated how important it was for children to be able to read independently by the age of eight. (refer to the quote below) There is nothing new in this, it was a fact that underpinned the work of Early Years co-ordinators and teachers in schools from the 1990s. It is refreshing to hear it emphasised again today. Hopefully instructional leaders in schools will recognise the need not only to ensure reading fluency in the early years but also emphasise the need to use quality children’s literature to engage students and enrich their lives. John Hattie in “Visible Learning for Literacy“ 2016 states that literacy is important because: Literacy is among the major antidotes for poverty; literacy makes your life better; literate people have more choices in their work and personal lives; literacy is great at teaching you how to think successfully; and literacy soon becomes the currency of all other learning. If we are to ensure that every child across our region can read independently by the age of 8 years we must do two things: deliver a comprehensive reading program with close monitoring of progress and implement effective interventions. Sharyn Donald Regional Director South-Western Victoria Region 16/03/17 The Melbourne Declaration on Educational Goals for Young Australians (MCEETYA 2008) recognises literacy as an essential skill for students in becoming successful learners and as a foundation for success in all learning areas. -

FARROW Erin-Thesis.Pdf

Somewhere Between: The Shifting Trends in the Narrative Strategies and Preoccupations of the Young Adult Realistic Fiction Genre in Australia Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy College of Arts Victoria University Erin Farrow 2017 Abstract. ‘Young adult realistic fiction’ is a classification used by contemporary publishers such as Random House, McGraw Hill Education and Scholastic, who define it as ‘stories with characters, settings, and events that could plausibly happen in true life’ (Scholastic 2014). From the first Australian young adult imprint in 1986 it has become possible to trace substantial shifts in the trends of genre. This thesis explores some of the ways that the narrative structures and preoccupations of contemporary Australian young adult realistic fiction novels have shifted, particularly in regards to the portrayal of the main protagonist’s self-awareness, the complexity of the subject matter being discussed and the unresolved nature of the novels’ endings. The significance of these shifting trends within the genre is explored by means of a creative component and an accompanying exegesis. Through my novel, Somewhere between, I aim to consider and build on the changing narrative structures and preoccupations of Australian novels of the young adult realistic fiction genre. The exegesis uses the examination of representative Australian YA novels published between 1986 and 2013 to demonstrate the shifting trends in these three main narrative structures and preoccupations. The gradual, steady, shift in the narrative structures and preoccupations of the genre away from stability and assurance gives evidence of shifting notions of childhood and adolescent subjectivity within contemporary Australian society.