The Australian Gothic Through the Novels of Sonya Hartnett

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Independent Scholar Shivaun Plozza the Troll Under the Bridge

Plozza The troll under the bridge Independent scholar Shivaun Plozza The troll under the bridge: should Australian publishers of young adult literature act as moral-gatekeepers? Abstract: In the world of Young Adult Literature, the perceived impact of certain texts on the moral, social and psychological development of its readers is a cause for debate. The question ‘what is suitable content for a pre-adult readership’ is one guaranteed to produce conflicting, polarising and impassioned responses. Within the context of this debate, the essay explores a number of key questions. Do publishers have a moral obligation to avoid certain topics or should they be pushing the boundaries of teen fiction further? Is it the role of the publisher to consider the impact of books they publish to a teenage audience? Should the potential impact of a book on its reader be considered ahead of a book’s potential to sell and make money? This article analyses criticism and praise for two ‘controversial’ Australian Young Adult books: Sonya Hartnett’s Sleeping Dogs (1997) and John Marsden’s Dear Miffy (1997). It argues that ‘issues-books’ are necessary to the development of teens, and publishers should continue to push the envelope of teen fiction while ensuring they make a concerted effort to produce quality, sensitive and challenging books for a teen market. Biographical note: Shivaun Plozza is a project editor, manuscript assessor and writer of YA fiction. Her debut novel, Frankie, is due for publication by Penguin in early 2016. She has published short stories, poetry and articles in various journals, both online and print, and has won numerous awards and fellowships. -

Middle-Road Congo Plan Is Offered UN by Bilateral Group

IM7I I Independent Dally I SH 14010 |HU<4 atlir. lisadtT uroufh rndtr. atciBd Ciui ft 7c PER COPY SSc PER WEEK VOL. 83, NO. 162 FaU U R»d Bank ao4 a AMUlonl MtiUof OWCM. RED BANK, N. J., FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 17, 1961 BY CARRIER PAGE ONE Salary Boosts ^^^ i . Middle-Road Congo Planned; Police Plan Is Offered UN Request More NEW SHREWSBURY — An ordinance providing By Bilateral Group pay raises for policemen, some borough employees and laborers was introduced last night by the Borough Council. ns Priest Slain Hope to Avert The measure, which will have • public hearing In KIVM Terror March 2, lists increases Storm U.S. Direct Clash for Jerome Reed, borough USUMBURA, Ruaada-Urundi (AP) — Congolese soldiers on clerk, up $400 to $6,100; Embassy the rampage killed • Belgian Of East-West Mrs. Ruth B. Crawford, To Pick Catholic priest yesterday in tax collector, up $300 to LAGOS, Nigeria (AP) — Bukavu, capital o( the Congo'* UNITED NATIONS, N. $5,500; Mrs. M. Jeannette Cobb, The American and Belgian Klvu Province, and arrested Y. (AP)—A group of Asian municipal court clerk, up $1,000 and beat up Anicet Kashamura, GOP Slate CONKRINCI AT THI UNITID NATIONS — Soviet Ambassador Valerian Zorin, left, Embassies were stormed and African nations moved to $2,400; Ernest Hiltbrunner, the No. 2 man of the pro-Com- today to seize the initiative road and sanitation department •nd Altksei E. Neiterenko, center, • member of the Soviet delegation, confera with ast night by screaming munist Lumumbist regime in supervisor, up $200 to $7,200, and Omar Loutfi, delegate from the United Arab Republic, before meeting of U.N. -

Beyond Good and Evil

Beyond Good and Evil Friedrich Nietzsche Helen Zimmern translation PREFACE SUPPOSING that Truth is a woman—what then? Is there not ground for suspecting that all philosophers, in so far as they have been dogmatists, have failed to understand women—that the terrible seriousness and clumsy importunity with which they have usually paid their addresses to Truth, have been unskilled and unseemly methods for winning a woman? Certainly she has never allowed herself to be won; and at present every kind of dogma stands with sad and discouraged mien—IF, indeed, it stands at all! For there are scoffers who maintain that it has fallen, that all dogma lies on the ground— nay more, that it is at its last gasp. But to speak seriously, there are good grounds for hoping that all dogmatizing in philosophy, whatever solemn, whatever conclusive and decided airs it has assumed, may have been only a noble puerilism and tyronism; and probably the time is at hand when it will be once and again understood WHAT has actually sufficed for the basis of such imposing and absolute philosophical edifices as the dogmatists have hitherto reared: perhaps some popular superstition of immemorial time (such as the soul-superstition, which, in the form of subject- and ego-superstition, has not yet ceased doing mischief): perhaps some play upon words, a deception on the part of grammar, or an audacious generalization of very restricted, very personal, very human— all-too-human facts. The philosophy of the dogmatists, it is to be hoped, was only a promise for thousands of years afterwards, as was astrology in still earlier times, in the service of which probably more labour, gold, acuteness, and patience have been spent than on any actual science hitherto: we owe to it, and to its "super- terrestrial" pretensions in Asia and Egypt, the grand style of architecture. -

Different Drummers

Special Issue: Different Drummers March/April 2013 Volume LXXXIX Number 2 ® Features Barbara Bader 21 Z Is for Elastic: The Amazing Stretch of Paul Zelinsky A look at the versatile artist’s career. Roger Sutton 30 Jack (and Jill) Be Nimble: An Interview with Mary Cash and Jason Low Independent publishers stay flexible and look to the future. Eugene Yelchin 41 The Price of Truth Reading books in a police state. Elizabeth Burns 47 Reading: It’s More Than Meets the Eye Making books accessible to print-disabled children. Columns Editorial Roger Sutton 7 See, It’s Not Just Me In which we celebrate the nonconforming among us. The Writer’s Page Polly Horvath and Jack Gantos 11 Two Writers Look at Weird Are they weird? What is weird, anyway? And will Jack ever reply to Polly? Different Drums What’s the strangest children’s book you’ve ever enjoyed? Elizabeth Bird 18 Seven Little Ones Instead Luann Toth 20 Word Girl Deborah Stevenson 29 Horrible and Beautiful Kristin Cashore 39 Embracing the Strange Susan Marston 46 New and Strange, Once Elizabeth Law 58 How Can a Fire Be Naughty? Christine Taylor-Butler 71 Something Wicked Mitali Perkins 72 Border Crossing Vaunda Micheaux Nelson 79 Wiggiling Sight Reading Leonard S. Marcus 54 Wit’s End: The Art of Tomi Ungerer A “willfully perverse and subversive individualist.” (continued on next page) March/April 2013 ® Columns (continued) Field Notes Elizabeth Bluemle 59 When Pigs Fly: The Improbable Dream of Bookselling in a Digital Age How one indie children’s bookstore stays SWIM HIGH ACROSS T H E SKY afloat. -

Sonya Hartnett Author of the Children of the King HC: 978-0-7636-6735-1 • E-Book: 978-0-7636-7042-9 272 Pages • Age 10 and Up

A conversation with sonya hartnett author of the Children of the King HC: 978-0-7636-6735-1 • E-book: 978-0-7636-7042-9 272 pages • Age 10 and up Q: You start with a scary opening scene. If I hadn’t been told that this was a “mild ghost story,” I might not have gotten past it. Some of your other writing can be very unsettling. What made you decide that this story would be more mild? A: Questionsofmildnessnevercameintoit.Anideacomestoyou,anditbringswithititsown spirit—someareeerie,somearequiet,someareloud,someareslinky,somearestrange.Iknew thiswouldbeastoryforchildrensetduringthewar.Theagegroupcreatescertainlimitsaround whatyoucanandcan’twrite.IneverthoughtofitasbeingaghoststoryasIwroteit,soIdidn’t spendanytimemakingtheboysscary.Iwantedthemtobeabletobemistakenforrealchildren bythereader,soIkeptalidontheirscariness.Theopeningsceneis,I’mtold,alittlescary.Ithink abookshouldstartwithabang,andsothesceneisakindofbang.IusedtoplayMurderinthe Darkasakid;itterrifiedme.Iplayitwithmydogsometimes;itstillterrifiesme. Q: What inspired you to write the story-within-the story, weaving the tale of a family evacuating from London to a country estate during World War II with the mystery of the missing princes, nephews of King Richard? How do those two elements, World War II and the mystery of the princes, resonate for you, if they do? A: I’vealwaysbeeninterestedinthestoryofRichardandtheprinces,andI’vealludedtoitafew timesinvariousnovels,butIalwayswantedtowritesomethingmoresubstantialaboutit—to reallylookinsidethecharacters’heads.I’vealsoalwaysfoundthewholeevacuationsagatobe -

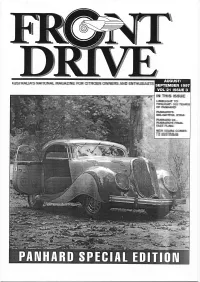

IN THIS ISSUE LIMELIGHT to TWILIGHT.Loo YEARS of PANHARD PANHARD's DELIGHTFUL DYNA PANHARD 24

AUSTRALIAS NATIONAL MAGAZINE FOR CITROEN OWNERS AND ENTHUSIASTS IN THIS ISSUE LIMELIGHT TO TWILIGHT.lOO YEARS OF PANHARD PANHARD'S DELIGHTFUL DYNA PANHARD 24 . PANHARD'S FINAL FAST FLING NEW XSARA COMES TO AUSTR,qLh FRC)NT DRTVE - AIJSTRALTA'S NATIONAL CITROEN MAGAZINE Published by The Gitro6n Classic Owners CIub of Australia lnc. CITROEN C].ASSIC OWNERS CLUB NANCE CI.ARKE 1984 OF AUSTRALIA INC. CCOCA MEMBERSHIP JACK WEAVER 1991 The Glub's and Front Drive's postal address is Annual Membership $30 P.O. Box 52, Deepdene Delivery Centre, Overseas Postage Add $g Victoria, 3103. CCOCA MEETINGS Our e-mail address is [email protected] Every fourth Wednesday of the month, except CCOCA lnc. is a member of the Association of December. Motoring Clubs. G.P.O. Box 2374V Melboume, Venue:- Canterbury Sports Ground Pavilion, Victoria, 3000. cnr. Chatham and Guilford Roads, publication The views expressed in this are not Canterlcury Victoria. Melways Ref 46 F10, necessarily those of CCOCA or its committee. Neither CCOCA, nor its Committee can accept any responsibility for any mechanical advice printed in, or adopted from Front Drive. And that means you can now pay for your subscriptions, rally fees, and not Ytsfr to mention the all important spare pafts in a mone convenient way 1997 COCCA COMMITTEE "What is that thing on the cover?", I hear you ask. I know it is not PRESIDENT - Peter Fitzgerald a Citro6n, it actually has nothing to do with Citro6n at all. But its 297 Moray Street, South Melbourne, younger siblings'do. lt is a Panhard Dynamic Type 140 for this Victoria, 3205 photograph a good deal the other Panhard material in Phone (03) s6e6 0866 (BH & AH) and, of Fa,r (03) 9696 0708 this issue I must thank Bruce Dickie. -

Bronxville Elementary School Summer Reading Suggestions 2019

Bronxville Elementary School Summer Reading Suggestions 2019 Table of Contents Ideas for Encouraging Reading……………………………………….p. 2 Resource Guide………………………………………………………….……….p. 3 Kindergarten into First Grade…………………………………….….p. 4 First into Second Grade…………………………………………...…….p. 10 Second into Third Grade…………………………….……………..……p. 16 Third, Fourth and Fifth Grade………………………………….……p. 20 Fifth Grade and up…………………………………………….……….……..p. 26 Please note: The listed books are only suggestions. No titles are required for reading and no child will be expected to read from the list. Books listed are chosen from a variety of sources. They include a wide variety of interests and a range of reading levels. Enjoy your summer! IDEAS FOR MAKING YOUR CHILD A LIFE-LONG LOVER OF BOOKS Picking up a book and reading for pleasure makes our minds grow. But some kids struggle with reading and for parents this can be very frustrating. Here are some things to keep in mind on ways to turn a young reader's reluctance into enthusiasm: • Encourage your child to read for fun, let them read books they enjoy. Forcing a child to read books that are either not interesting or too difficult will only discourage them from reading. Use their interests and hobbies as starting points. • Don’t rule out magazines! The short, content-based articles are often written at an easy reading level and will spark their interest in a variety of topics. Most bookstore chains have a huge selection of magazines to appeal to almost every interest. • Read aloud to children of all ages. There is no age cutoff for reading aloud. The pleasure of listening to you read, rather than struggling alone, may restore your child's initial enthusiasm for books and reading. -

QUT Digital Repository

QUT Digital Repository: http://eprints.qut.edu.au/ Muller, Vivienne (2008) Lost children and imaginary mothers in Sonya Hartnett's "Of a Boy". Hecate, 34(1). pp. 159-174. © Copyright 2008 please consult the author. Lost children and imaginary mothers in Sonya Harnett’s Of A Boy In Powers of Horror, Julia Kristeva writes about lost children.1 These are what she calls ‘dejects’, 2 who, in the psychodrama of subject formation, fail to fully absent the body of the mother, to accept the Law of the Father and the Symbolic, and subsequently to establish ‘clear boundaries which constitute the object-world for normal subjects’.3 Dejects are ‘strays’ looking for a place to belong, a place that is bound up with the Imaginary mother of the pre-Oedipal period. Kristeva’s sketch of the deject as one who is unable to negotiate a proper path to the Symbolic is useful to a reading of Hartnett’s Of A Boy (2002)4, a novel that also deals with lost children and imaginary mothers. However in its portrayal of children who are doomed to never achieve adulthood, Of A Boy enacts a haunting retrieval of the pre-Oedipal from the dark side of phallocentric representation, privileging the semiotic (Kristeva’s concept) and the maternal as necessary disruptive checks on a patriarchal Symbolic Order. In reading the narrative in this way, this essay does not seek to foreclose on other interpretations which may more fully illuminate the material and historical contexts in which Hartnett’s stories of abandoned and lost mothers and children are activated. -

Talking Leaves 2009-2010

TALKING LEAVES COPYRIGHT 2009-2010 II Talking Leaves Staff Production Editors Oshu Huddleston, Senior Editor Cole Billman, Assistant Editor Production Assistant Joe Land Faculty Sponsor Lisa Siefker Bailey, Ph.D. Advisory Editor Katherine V. Wills, Ph.D. Copy Editors Jerry Baker Cole Billman Lindsey Daugherty Oshu Huddleston Abby Jones Joe Land Copyright 2009-2010 by the Trustees of Indiana University. Upon publication, copyright reverts to the author/artist. We retain the right to electronically archive and publish all issues for posterity and the general public. Talking Leaves is published annually by the Talking Leaves IUPUC Division of Liberal Arts Editorial Board. Statement of Policy and Purpose Talking Leaves accepts original works of fiction, poetry, photography, and line drawings from students at Indiana University- Purdue University Columbus. Each anonymous submission is reviewed by a Selection Roundtable and is judged solely on artistic merit. III IV TABLE OF CONTENTS VII – A WORD FROM THE FACULTY SPONSOR 1 - Beachcomber - poem by Beth McQueen 1 - The Flight - poem by Cole Billman 2 - Drifting - poem by Sarah Akemon 3 - Water PROOF - poem by Joe Land 4 - Noir Goode - short fiction by Oshu Huddleston 7 - Untitled (Short heaves) - poem by Joe Land 8 - National Treasure - poem by Sarah Akemon 8 - Untitled (1) - poem by Beth McQueen 8 - Untitled (2) - poem by Beth McQueen 9 - what is this sedentary thing - poem by Joe Land 9 - In the Hour of Our Death - poem by Sarah Akemon 10 - Write Shitty - poem by Sherry Traylor 10 - Blah. Eck! -

CCBC Choices 2013 || Cooperative Children's Book Center || University

CCBC Choices 2013 CCBC Choices 2013 Kathleen T. Horning Merri V. Lindgren Megan Schliesman Cooperative Children’s Book Center School of Education University of Wisconsin–Madison Copyright ©2013, Friends of the CCBC, Inc. ISBN–10: 0–931641–23–3 ISBN–13: 978–0–931641–23–7 CCBC Choices 2013 was produced by the office of University Communications, University of Wisconsin–Madison. Cover design: Lois Ehlert This publication was created by librarians at the Cooperative Children’s Book Center, School of Education, University of Wisconsin–Madison. Funding for the production and printing was provided by the Friends of the CCBC, Inc. For information, see the Appendices, or go to www.education.wisc.edu/ccbc/. CCBC Choices 2013 3 Contents Acknowledgments .............................................4 Introduction .................................................5 Organization of CCBC Choices 2013 ..............................6 The Charlotte Zolotow Award ...................................8 A Few Observations on Publishing in 2012 .......................10 The Choices Science, Technology, and the Natural World .....................14 Seasons and Celebrations ....................................20 Folklore, Mythology, and Traditional Literature. 21 Historical People, Places, and Events ...........................22 Biography and Autobiography ................................30 Contemporary People, Places, and Events .......................37 Understanding Oneself and Others ............................41 The Arts ................................................42 -

The Archaic Shudder? Toward a Poetics of the Sublime (In Two Sections: Creative and Critical)

Title The Archaic Shudder? Toward a poetics of the sublime (in two sections: creative and critical) Student Name Dan Disney Diploma of Arts (Editing), RMIT Bachelor of Arts, Monash University Master of Creative Arts (Research), University of Melbourne This thesis is submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by creative work (50%) and dissertation (50%), School of Culture and Communication, University of Melbourne. Submitted 15th September, 2009. 1 2 Abstract This cross-disciplinary investigation moves toward that sub-genre in aesthetics, the theory of creativity. After introducing my study with a re-reading of Heidegger’s essay, ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’, I appropriate into a collection of poems ideas from Plato, Kant, Heidegger, Wittgenstein, and a range of post-philosophical theorists. Next, after Murmur and Afterclap, in the critical section of my investigation I formulate a poetics of the sublime, and move closer to my own specialist term, poeticognosis. With this term, I set out to designate a particular style of apprehending-into-language, after wonder, as it pertains (I argue) to creative producers. Section One Murmur and Afterclap The poetry submitted here does not arise simply out of a theoretical position or theoretical concerns, and it is not in any sense exemplary or programmatic. It is, however, related in complex ways to the issues raised later in the critical section of my investigation, and indeed has provoked − necessitated − my theoretical discussion (rather than the other way around). The poems contained in this section of my investigation draw from the many documents I have encountered in my attempt to shape a discourse with philosophy. -

March / April 2018 Issue

SAHJournal ISSUE 291 MARCH / APRIL 2018 SAH Journal No. 291 • March / April 2018 $5.00 US1 Contents 3 PRESIDENT’S PERSPECTIVE SAHJournal 4 CENTURY OF AUSTRALIAN AUTOMOBILE MANUFACTURE ENDS ISSUE 291 • MARCH/APRIL 2018 A HISTORICAL REVIEW AND PERSPECTIVE 8 SAH IN PARIS XXIII THE SOCIETY OF AUTOMOTIVE HISTORIANS, INC. 9 RÉTROMOBILE 43 An Affiliate of the American Historical Association 11 BOOK REVIEWS Billboard Officers Louis F. Fourie President SAH Board Nominations: related to Rolls-Royce of America, Inc. This Edward Garten Vice President Robert Casey Secretary The SAH Nominating Committee is includes promotional images of Rolls-Royce Rubén L. Verdés Treasurer seeking nominations for positions on the automobiles photographed by John Adams board through 2021. Please address all Davis. Other automotive history subjects Board of Directors nominations to the chair, Andrew Beckman are sought too. Only digital images are Andrew Beckman (ex-officio) ∆ Robert G. Barr ∆ at [email protected]. needed. Accordingly, if you would like your H. Donald Capps # antique automotive documents and photos Donald J. Keefe ∆ Wanted: Contributors! The SAH digitized for free, just contact the editor at Kevin Kirbitz # Journal invites contributors for articles and [email protected] to confirm the assign- Carla R. Lesh † book reviews. (A book reviewer that can read ment. Then mail your material, and it will be John A. Marino # Robert Merlis † Japanese is currently needed.) Please contact mailed back to you with the digital media. Matthew Short ∆ the editor directly. Thank you! Vince Wright † Your Billboard: What are you Terms through October (†) 2018, (∆) 2019, and (#) 2020 Correction: The masthead of issues working on?..