Heritage Handbook A5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ORNITHOLOGIST VOLUME 44 - PARTS 1&2 - November - 2019

SOUTH AUSTRALIAN ORNITHOLOGIST VOLUME 44 - PARTS 1&2 - November - 2019 Journal of The South Australian Ornithological Association Inc. In this issue: Variation in songs of the White-eared Honeyeater Phenotypic diversity in the Copperback Quailthrush and a third subspecies Neonicotinoid insecticides Bird Report, 2011-2015: Part 1, Non-passerines President: John Gitsham The South Australian Vice-Presidents: Ornithological John Hatch, Jeff Groves Association Inc. Secretary: Kate Buckley (Birds SA) Treasurer: John Spiers FOUNDED 1899 Journal Editor: Merilyn Browne Birds SA is the trading name of The South Australian Ornithological Association Inc. Editorial Board: Merilyn Browne, Graham Carpenter, John Hatch The principal aims of the Association are to promote the study and conservation of Australian birds, to disseminate the results Manuscripts to: of research into all aspects of bird life, and [email protected] to encourage bird watching as a leisure activity. SAOA subscriptions (e-publications only): Single member $45 The South Australian Ornithologist is supplied to Family $55 all members and subscribers, and is published Student member twice a year. In addition, a quarterly Newsletter (full time Student) $10 reports on the activities of the Association, Add $20 to each subscription for printed announces its programs and includes items of copies of the Journal and The Birder (Birds SA general interest. newsletter) Journal only: Meetings are held at 7.45 pm on the last Australia $35 Friday of each month (except December when Overseas AU$35 there is no meeting) in the Charles Hawker Conference Centre, Waite Road, Urrbrae (near SAOA Memberships: the Hartley Road roundabout). Meetings SAOA c/o South Australian Museum, feature presentations on topics of ornithological North Terrace, Adelaide interest. -

Heritage of the Birdsville and Strzelecki Tracks

Department for Environment and Heritage Heritage of the Birdsville and Strzelecki Tracks Part of the Far North & Far West Region (Region 13) Historical Research Pty Ltd Adelaide in association with Austral Archaeology Pty Ltd Lyn Leader-Elliott Iris Iwanicki December 2002 Frontispiece Woolshed, Cordillo Downs Station (SHP:009) The Birdsville & Strzelecki Tracks Heritage Survey was financed by the South Australian Government (through the State Heritage Fund) and the Commonwealth of Australia (through the Australian Heritage Commission). It was carried out by heritage consultants Historical Research Pty Ltd, in association with Austral Archaeology Pty Ltd, Lyn Leader-Elliott and Iris Iwanicki between April 2001 and December 2002. The views expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of the South Australian Government or the Commonwealth of Australia and they do not accept responsibility for any advice or information in relation to this material. All recommendations are the opinions of the heritage consultants Historical Research Pty Ltd (or their subconsultants) and may not necessarily be acted upon by the State Heritage Authority or the Australian Heritage Commission. Information presented in this document may be copied for non-commercial purposes including for personal or educational uses. Reproduction for purposes other than those given above requires written permission from the South Australian Government or the Commonwealth of Australia. Requests and enquiries should be addressed to either the Manager, Heritage Branch, Department for Environment and Heritage, GPO Box 1047, Adelaide, SA, 5001, or email [email protected], or the Manager, Copyright Services, Info Access, GPO Box 1920, Canberra, ACT, 2601, or email [email protected]. -

A Review of Lake Frome & Strzelecki Regional Reserves 1991-2001

A Review of Lake Frome and Strzelecki Regional Reserves 1991 – 2001 s & ark W P il l d a l i f n e o i t a N South Australia A Review of Lake Frome and Strzelecki Regional Reserves 1991 – 2001 Strzelecki Regional Reserves Lake Frome This review has been prepared and adopted in pursuance to section 34A of the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972. Published by the Department for Environment and Heritage Adelaide, South Australia July 2002 © Department for Environment and Heritage ISBN: 0 7590 1038 2 Prepared by Outback Region National Parks & Wildlife SA Department for Environment and Heritage Front cover photographs: Lake Frome coastline, Lake Frome Regional Reserve, supplied by R Playfair and reproduced with permission. Montecollina Bore, Strzelecki Regional Reserve, supplied by C. Crafter and reproduced with permission. Department for Environment and Heritage TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ................................................................................................................................................iii LIST OF TABLES..................................................................................................................................................iii LIST OF ACRONYMS and ABBREVIATIONS...................................................................................................iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ......................................................................................................................................iv FOREWORD .......................................................................................................................................................... -

Chapter 18 Non-Aboriginal Cultural Heritage

NON-ABORIGINAL CULTURAL HERITAGE 18 18.1 InTRODUCTION During the 1880s, the South Australian Government assisted the pastoral industry by drilling chains of artesian water wells Non-Aboriginal contact with the region of the EIS Study Area along stock routes. These included wells at Clayton (on the began in 1802, when Matthew Flinders sailed up Spencer Gulf, Birdsville Track) and Montecollina (on the Strzelecki Track). naming Point Lowly and other areas along the shore. Inland The government also established a camel breeding station at exploration began in the early 1800s, with the primary Muloorina near Lake Eyre in 1900, which provided camels for objective of finding good sheep-grazing land for wool police and survey expeditions until 1929. production. The region’s non-Aboriginal history for the next 100 years was driven by the struggle between the economic Pernatty Station was established in 1868 and was stocked with urge to produce wool and the limitations imposed by the arid sheep in 1871. Other stations followed, including Andamooka environment. This resulted in boom/crash cycles associated in 1872 and Arcoona and Chances Swamp (which later became with periods of good rains or drought. Roxby Downs) in 1877 (see Chapter 9, Land Use, Figures 9.3 18 and 9.4 for location of pastoral stations). A government water Early exploration of the Far North by Edward John Eyre and reserve for travelling stock was also established further south Charles Sturt in the 1840s coincided with a drought cycle, in 1882 at a series of waterholes called Phillips Ponds, near and led to discouraging reports of the region, typified by what would later be the site of Woomera. -

2018 September Quarter

Hancock Agriculture September 2018 3, Issue 3 Hancock Kidman Making us the best Cattle Company National Agriculture and Related Industries Day National Agriculture and Related Industries Day will be held again this year on Wednesday 21 November 2018. To all pastoral properties and employees you should start thinking of how we can all start celebrating this important day. Santa Gertrudis and Coolibah Composite bulls in forage oats on Rockybank Staon Inside this issue Naonal Agriculture and Related Industries Day ................1 Wed, 21 November 2018 Message from Your Chairman .....2 Sydney CBD Speech by Mrs Gina Rinehart Reserve your tables or seats AmCham 50th Anniversary Gala now for the annual gala dinner Dinner .........................................4 (Akubras and boots welcome!) [email protected] Message from Your CEO ..............10 Capex / Opex upgrades ...............11 General Manager Updates ..........12 Health and Wellbeing Mental Health Month..................14 Staon News ...............................15 Done Training Courses ................16 Future Important Dates Staff Achievements Hancock Agriculture 2019 recruitment ad ...........................17 Santa Gertrudis cale at S. Kidman & Co Pty Ltd Naryilco Staon, Qld Message from Your Chairman Dear team members I hope you are all doing well and I appreciate the wonderful efforts and commitment that you are making including through the drought – rain is, together with you all, the key to life on staons and farms too. We should see a moratorium on all government fees and charges for at least two years to allow people to recover on the land. Of course this is not the first me I have called for red tape and taxes to be reduced, for instance I refer to this in my speech to AmCham in the newsleer, and why this has been so successful in the USA, as making people more able to get on with business and get out of debt, is much beer than loans which push people further into debt, with interest and me consuming reporng obligaons. -

Rare Books Lib

RBTH 2239 RARE BOOKS LIB. S The University of Sydney Copyright and use of this thesis This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copynght Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act gran~s the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author's moral rights if you: • fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work • attribute this thesis to another author • subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author's reputation For further information contact the University's Director of Copyright Services Telephone: 02 9351 2991 e-mail: [email protected] Camels, Ships and Trains: Translation Across the 'Indian Archipelago,' 1860- 1930 Samia Khatun A thesis submitted in fuUUment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History, University of Sydney March 2012 I Abstract In this thesis I pose the questions: What if historians of the Australian region began to read materials that are not in English? What places become visible beyond the territorial definitions of British settler colony and 'White Australia'? What past geographies could we reconstruct through historical prose? From the 1860s there emerged a circuit of camels, ships and trains connecting Australian deserts to the Indian Ocean world and British Indian ports. -

Well Maintained Bores Last Longer

November 2015 Issue 75 ACROSS THE OUTBACK Montecollina Bore Well maintained bores last longer The SAAL NRM Board would like to remind water users in the 01 BOARD NEWS SA Arid Lands region who have a bore under their care and 01 Well maintained bores last longer control to undertake simple, routine maintenance to reduce 02 LEB partnership wins world’s highest river management honour risks to water supplies, prevent costly and inconvenient 04 LAND MANAGEMENT breakdowns, and to meet their legal obligations. 04 Innovative ‘Spatial Hub’ lands in The region’s largest water resource is the The review of 289 artesian bores in the Far South Australia Great Artesian Basin (GAB) which provides North Prescribed Wells Area was undertaken 05 Grader workshops help fight soil a vital supply of groundwater for the to establish a comprehensive picture of the erosion continued operation of our key industries condition of the artesian bores in South 06 Women’s Retreat hailed a success (tourism, pastoral, mining, gas and Australia. petroleum) and to meet the needs of our It highlighted that maintenance needs to 07 THREATENED SPECIES communities and wildlife. improve. 07 Are Ampurtas making a comeback? To safeguard the sustainability of the In recent decades, governments, industry 08 SA ARID LANDS – IT’S YOUR GAB and other groundwater aquifers the and individuals have invested significantly PLACE Far North Prescribed Wells Area Water in bore rehabilitation and installing piped Allocation Plan was adopted in 2009 after a reticulation systems to deliver GAB water 12 VOLUNTEERS planning process led by the Board under the efficiently. -

Environmental Impact Report: Geophysical Operations

South Australian Cooper Basin Operators Environmental impact report: geophysical operations Prepared for South Australian Cooper Basin Operators June 2006 1 Prepared by: Operations Geophysics Santos Ltd 91 King William Street, Adelaide GPO Box 2319, Adelaide, SA, 5001 Phone +61 8 8224 7200 Fax +61 8 8224 7636 2 South Australian Cooper Basin operators. Environmental impact report: geophysical operations. CONTENTS 1 SUMMARY .........................................................................................................................................................6 2 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................7 2.1 Cooper Basin Operators .....................................................................................................................................7 2.2 Location...............................................................................................................................................................7 2.3 Petroleum resource rationale..............................................................................................................................7 2.4 Legislative outline................................................................................................................................................9 3 LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORK..........................................................................................................................10 3.1 Petroleum -

On Track 2010-2011

ON TRACK Delivering NRM in the SA Arid Lands 2010-11 ON TRACK Delivering natural resources management in the SA Arid Lands 2010-11 Protecting our land, plants and animals Understanding and securing our water resources Supporting our industries and communities 1 Welcome It is with great pleasure that I introduce this first edition of On Track. Having now completed the first year the achievements of former Presiding of delivery of the South Australian Arid Member Chris Reed, previous members Lands (SAAL) Regional Natural Resources of the Board, and General Manager John Management (NRM) Plan which sets the Gavin. Almost all of the activities you will direction for natural resources management read about here were initiated through their in the region to 2020, On Track is a report efforts and the current Board is building on to our community on the progress we made their endeavours. in 2010-11 on meeting the Plan’s targets. This year was also marked by the True to the SAAL NRM Board’s platform establishment of the new Department of and the spirit of natural resources Environment and Natural Resources in July management, On Track’s focus is on 2010 which brings together staff from the community. Outback office of the former Department We showcase the variety of projects and for Environment and Heritage and the staff activities where community members are of the SAAL NRM Board. working with the Board. This new integrated service will use a We share with you the experiences of landscape approach to manage natural some of the landholders and community resources across public and private land members involved with our programs and provide a single face for environment including Ecosystem Management and natural resources services in our Understanding™, Pest Management and region. -

National Recovery Plan for the Plains Mouse Pseudomys Australis 2012

National Recovery Plan for the Plains Mouse Pseudomys australis 2012 - 1 - This plan should be cited as follows: Moseby, K. (2012) National Recovery Plan for the Plains Mouse Pseudomys australis. Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources, South Australia. Published by the Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources, South Australia. Adopted under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999: [date to be supplied] ISBN : 978-0-9806503-1-0 © Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources, South Australia. This publication is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Government of South Australia. Requests and inquiries regarding reproduction should be addressed to: Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources GPO Box 1047 ADELAIDE SA 5001 Note: This recovery plan sets out the actions necessary to stop the decline of, and support the recovery of, the listed threatened species or ecological community. The Australian Government is committed to acting in accordance with the plan and to implementing the plan as it applies to Commonwealth areas. The plan has been developed with the involvement and cooperation of a broad range of stakeholders, but individual stakeholders have not necessarily committed to undertaking specific actions. The attainment of objectives and the provision of funds may be subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved. Proposed actions may be subject to modification over the life of the plan due to changes in knowledge. Queensland disclaimer: The Australian Government, in partnership with the Queensland Department of Environment and Heritage Protection, facilitates the publication of recovery plans to detail the actions needed for the conservation of threatened native wildlife. -

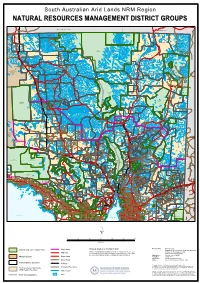

Natural Resources Management District Groups

South Australian Arid Lands NRM Region NNAATTUURRAALL RREESSOOUURRCCEESS MMAANNAAGGEEMMEENNTT DDIISSTTRRIICCTT GGRROOUUPPSS NORTHERN TERRITORY QUEENSLAND Mount Dare H.S. CROWN POINT Pandie Pandie HS AYERS SIMPSON DESERT RANGE SOUTH Tieyon H.S. CONSERVATION PARK ALTON DOWNS TIEYON WITJIRA NATIONAL PARK PANDIE PANDIE CORDILLO DOWNS HAMILTON DEROSE HILL Hamilton H.S. SIMPSON DESERT KENMORE REGIONAL RESERVE Cordillo Downs HS PARK Lambina H.S. Mount Sarah H.S. MOUNT Granite Downs H.S. SARAH Indulkana LAMBINA Todmorden H.S. MACUMBA CLIFTON HILLS GRANITE DOWNS TODMORDEN COONGIE LAKES Marla NATIONAL PARK Mintabie EVERARD PARK Welbourn Hill H.S. WELBOURN HILL Marla - Oodnadatta INNAMINCKA ANANGU COWARIE REGIONAL PITJANTJATJARAKU Oodnadatta RESERVE ABORIGINAL LAND ALLANDALE Marree - Innamincka Wintinna HS WINTINNA KALAMURINA Innamincka ARCKARINGA Algebuckinna Arckaringa HS MUNGERANIE EVELYN Mungeranie HS DOWNS GIDGEALPA THE PEAKE Moomba Evelyn Downs HS Mount Barry HS MOUNT BARRY Mulka HS NILPINNA MULKA LAKE EYRE NATIONAL MOUNT WILLOUGHBY Nilpinna HS PARK MERTY MERTY Etadunna HS STRZELECKI ELLIOT PRICE REGIONAL CONSERVATION ETADUNNA TALLARINGA PARK RESERVE CONSERVATION Mount Clarence HS PARK COOBER PEDY COMMONAGE William Creek BOLLARDS LAGOON Coober Pedy ANNA CREEK Dulkaninna HS MABEL CREEK DULKANINNA MOUNT CLARENCE Lindon HS Muloorina HS LINDON MULOORINA CLAYTON Curdimurka MURNPEOWIE INGOMAR FINNISS STUARTS CREEK SPRINGS MARREE ABORIGINAL Ingomar HS LAND CALLANNA Marree MUNDOWDNA LAKE CALLABONNA COMMONWEALTH HILL FOSSIL MCDOUAL RESERVE PEAK Mobella -

Arckaringa Basin Geophysical Operations Environmental Impact

Arckaringa Basin Geophysical Operations Environmental Impact Report July 2007 Prepared for: SAPEX Ltd 2 Grenfell St Kent Town SA 5067 (PO Box 108 Kent Town SA 5071) ph: (08) 8363 3311 fax: (08) 8363 3399 [email protected] www.sapex.com.au Prepared by: RPS Ecos ABN 57 081 918 194 26 Greenhill Road Wayville SA 5034 ph: (08) 8357 0400 fax: (08) 8357 0411 [email protected] www.rpsecos.com.au © RPS Ecos 2007 DOCUMENT CONTROL ENV740- Arckaringa Basin Geophysical Operations EIR Document Revision Revision Compiled by Checked by Approved by Comment Reference Number Date Issued to client for 720-AB Seismic EIR A 30May07 ZB/SM SM SM review 0 26Jun07 ZB/SM SM SM Submission to PIRSA Incorporation of feedback from PIRSA 1 24Jul07 ZB/SM SM SM Submission for public release SAPEX Arckaringa Basin Geophysical Operations - Environmental Impact Report Contents 1 Introduction................................................................................................1 1.1 Location .............................................................................................1 1.2 Project Proponent..............................................................................1 1.3 About this Document .........................................................................1 2 Legislative Framework..............................................................................3 2.1 Petroleum Act and Regulations.........................................................3 2.2 Statement of Environmental Objectives ............................................3