Conrick of Nappa Merrie H. M. Tolcher

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Articles and Books About Western and Some of Central Nsw

Rusheen’s Website: www.rusheensweb.com ARTICLES AND BOOKS ABOUT WESTERN AND SOME OF CENTRAL NSW. RUSHEEN CRAIG October 2012. Last updated: 20 March 2013 Copyright © 2012 Rusheen Craig Using the information from this document: Please note that the research on this web site is freely provided for personal use only. Site users have the author's permission to utilise this information in personal research, but any use of information and/or data in part or in full for republication in any printed or electronic format (regardless of commercial, non-commercial and/or academic purpose) must be attributed in full to Rusheen Craig. All rights reserved by Rusheen Craig. ________________________________________________________________________________________________ Wentworth Combined Land Sales Copyright © 2012 Rusheen Craig 1 Contents THE EXPLORATION AND SETTLEMENT OF THE WESTERN PLAINS. ...................................................... 6 Exploration of the Bogan. ................................................................................................................................... 6 Roderick Mitchell on the Darling. ...................................................................................................................... 7 Exploration of the Country between the Lachlan and the Darling ...................................................................... 7 Occupation of the Country. ................................................................................................................................ 8 Occupation -

Heritage of the Birdsville and Strzelecki Tracks

Department for Environment and Heritage Heritage of the Birdsville and Strzelecki Tracks Part of the Far North & Far West Region (Region 13) Historical Research Pty Ltd Adelaide in association with Austral Archaeology Pty Ltd Lyn Leader-Elliott Iris Iwanicki December 2002 Frontispiece Woolshed, Cordillo Downs Station (SHP:009) The Birdsville & Strzelecki Tracks Heritage Survey was financed by the South Australian Government (through the State Heritage Fund) and the Commonwealth of Australia (through the Australian Heritage Commission). It was carried out by heritage consultants Historical Research Pty Ltd, in association with Austral Archaeology Pty Ltd, Lyn Leader-Elliott and Iris Iwanicki between April 2001 and December 2002. The views expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of the South Australian Government or the Commonwealth of Australia and they do not accept responsibility for any advice or information in relation to this material. All recommendations are the opinions of the heritage consultants Historical Research Pty Ltd (or their subconsultants) and may not necessarily be acted upon by the State Heritage Authority or the Australian Heritage Commission. Information presented in this document may be copied for non-commercial purposes including for personal or educational uses. Reproduction for purposes other than those given above requires written permission from the South Australian Government or the Commonwealth of Australia. Requests and enquiries should be addressed to either the Manager, Heritage Branch, Department for Environment and Heritage, GPO Box 1047, Adelaide, SA, 5001, or email [email protected], or the Manager, Copyright Services, Info Access, GPO Box 1920, Canberra, ACT, 2601, or email [email protected]. -

Innamincka Regional Reserve About

<iframe src="https://www.googletagmanager.com/ns.html?id=GTM-5L9VKK" height="0" width="0" style="display:none;visibility:hidden"></iframe> Innamincka Regional Reserve About Check the latest Desert Parks Bulletin (https://cdn.environment.sa.gov.au/parks/docs/desert-parks-bulletin- 21092021.pdf) before visiting this park. Innamincka Regional Reserve is a park of contrasts. Covering more than 1.3 million hectares of land, ranging from the life-giving wetlands of the Cooper Creek system to the stark arid outback, the reserve also sustains a large commercial beef cattle enterprise, and oil and gas fields. The heritage-listed Innamincka Regional Reserve park headquarters and interpretation centre gives an insight into the natural history of the area, Aboriginal people, European settlement and Australia's most famous explorers, Burke and Wills. From the interpretation centre, visit the sites where Burke and Wills died, and the historic Dig Tree site (QLD) which once played a significant part in their ill-fated expedition. Shaded by the gums, the waterholes provide a relaxing place for a spot of fishing or explore the creek further by canoe or boat. Opening hours Open daily. Fire safety and information Listen to your local area radio station (https://www.cfs.sa.gov.au/public/download.jsp?id=104478) for the latest updates and information on fire safety. Check the CFS website (https://www.cfs.sa.gov.au/site/home.jsp) or call the CFS Bushfire Information Hotline 1800 362 361 for: Information on fire bans and current fire danger ratings (https://www.cfs.sa.gov.au/site/bans_and_ratings.jsp) Current CFS warnings and incidents (https://www.cfs.sa.gov.au/site/warnings_and_incidents.jsp) Information on what to do in the event of a fire (https://www.cfs.sa.gov.au/site/prepare_for_a_fire.jsp) Please refer to the latest Desert Parks Bulletin (https://cdn.environment.sa.gov.au/parks/docs/desert-parks-bulletin- 21092021.pdf) for current access and road condition information. -

Chapter 18 Non-Aboriginal Cultural Heritage

NON-ABORIGINAL CULTURAL HERITAGE 18 18.1 InTRODUCTION During the 1880s, the South Australian Government assisted the pastoral industry by drilling chains of artesian water wells Non-Aboriginal contact with the region of the EIS Study Area along stock routes. These included wells at Clayton (on the began in 1802, when Matthew Flinders sailed up Spencer Gulf, Birdsville Track) and Montecollina (on the Strzelecki Track). naming Point Lowly and other areas along the shore. Inland The government also established a camel breeding station at exploration began in the early 1800s, with the primary Muloorina near Lake Eyre in 1900, which provided camels for objective of finding good sheep-grazing land for wool police and survey expeditions until 1929. production. The region’s non-Aboriginal history for the next 100 years was driven by the struggle between the economic Pernatty Station was established in 1868 and was stocked with urge to produce wool and the limitations imposed by the arid sheep in 1871. Other stations followed, including Andamooka environment. This resulted in boom/crash cycles associated in 1872 and Arcoona and Chances Swamp (which later became with periods of good rains or drought. Roxby Downs) in 1877 (see Chapter 9, Land Use, Figures 9.3 18 and 9.4 for location of pastoral stations). A government water Early exploration of the Far North by Edward John Eyre and reserve for travelling stock was also established further south Charles Sturt in the 1840s coincided with a drought cycle, in 1882 at a series of waterholes called Phillips Ponds, near and led to discouraging reports of the region, typified by what would later be the site of Woomera. -

Artesian Wells As a Means of Water Supply

m ^'7^ ^'^^ Cornell University Library TD 410.C88 Artesian wells as a means of water suppi 3 1924 004 406 827 (fimntW Winivmii^ Jibing BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME FROM THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT OF Hcntg W. Sage X891 .JJJA ^ 'i-JtERliNC Llfif-^RV s Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924004406827 ARTESIAN WELLS. ARTESIAN WELLS As a Means of Water Supply, including an account of The Rise, Progress, and Present State of the Art of Boring FOR Water in Europe, Asia and America ; Progress in the Australian Colonies ; A Treatise on the Water-bearing Rocks ; Permanence OF Supplies ; The Most Approved Machinery for, and the Cost of Boring, WITH Form of Contract, etc. ; Treatise on Irrigation from Artesian Wells ; AND ON Sub-artesian or Shallow Boring, etc. WALTER GIBBONS COX, C.E., ASSOC. INST. C.E.'S, LONDON, 1869. PRICE, SEVEN SHILLINGS AND SIXPENCE. BRISBANE, SYDNEY, MELBOURNE, AND ADELAIDE. Published by Sapsford & Co,, Adelaide Street, Brisbane. Sep., iSqs- 1895, DEDICATED BY PERMISSION TO MY ESTEEMED AND EARLIEST PATRON IN QUEENSLAND, Sir THOMAS M'lLWRAITH, C.E., K.C.M.G. LATE PREMIER OF QUEENSLAND. — PREFACE A First edition of this Book entitled, " On Artesian WeDs as a Means of Water Supply for Country Districts," was published in Brisbane in 1883. It was based upon papers published for me in the Leader newspaper, Melbourne, in 1878, one year before the first Artesian Bore was made in Australia— that at Kallara Station, New South Wales, in 1879, and two years before what is claimed to be the first artesian bore made in Australia—that at Sale, in Victoria—was commenced, advocating the utilisation of artesian supplies in this country. -

Innamincka/Cooper Creek State Heritage Area Innamincka/Cooper Creek Was Declared a State Heritage Area on 16 May 1985

Innamincka/Cooper Creek State Heritage Area Innamincka/Cooper Creek was declared a State Heritage Area on 16 May 1985. HISTORY Innamincka and Cooper Creek have a rich history. The area has also been associated with many other facets of the state's history since colonial settlement. Names such as Charles Sturt, Sidney Kidman, Cordillo Downs, the Australian Inland Mission and the Reverend John Flynn are intrinsically woven into the stories of Innamincka and the Cooper Creek. Its significance for Aboriginal people spans thousands of years as a trade route and a source of abundant food and fresh water. The area's Aboriginal history also includes significant contacts with explorers, pastoralists and settlers. Many sources believe that the name 'Innamincka' comes from two Aboriginal words meaning ' your shelter' or 'your home'. European contact with the region came first with the explorers and later with the establishment of the pastoral industry, transport routes and service centres. Cooper Creek was named by Captain Charles Sturt on 13 October 1845, when he crossed the watercourse at a point approximately 24 kilometres west of the current Innamincka township. The water was very low at the time, hence his use of the term 'creek' rather than 'river' to describe what often becomes a deep torrent of water. Charles Cooper, after whom the waterway was named, was a South Australian judge - later Chief Justice Sir Charles Cooper. On the same expedition, Sturt also named the Strzelecki Desert after the eccentric Polish explorer, Paul Edmund de Strzelecki, who was the first European to climb and name Mount Kosciusko. -

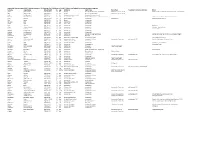

Grs 513/11/P

GPO Box 464 Adelaide SA 5001 Tel (+61 8) 8204 8791 Fax (+61 8) 8260 6133 DX:336 [email protected] www.archives.sa.gov.au Special List GRS 513 Lodged company documents of defunct companies Series These files contain documents lodged by companies in Description accordance with the varying Companies Acts. Company files may contain some or all of the following lodged documents: Memorandum of Agreement, Articles of Association, Certificate of Incorporation, lists of shareholders, lists of directors, special resolutions ie. issues of shares, underwriting agreements and annual returns. Note: The term 'defunct' should not be understood to refer to the company. In this context it refers to the file being defunct, although given the age of the records some of the companies will have become defunct. Series date range 1844 - 1986 Agency State Records of South Australia responsible Access Open. Determination Contents 1874 – 1935 1 June 2016 GRS 513/11/P DEFUNCT COMPANIES FILES 4/1S74 The Stonyfell Olive Company Limited (Scm) \ 4/1874 The Stonyfell Olive Co. Limited (1 file) 1/1875 The East End Market Company (16cm)) 1/1S75 The East End Market Coy. Ltd. (1 file) 3/1SSO The Executor Trust & Agency Company of South Australia Limited (9cm &9cm)(2 bundles)) 10/1S7S Adelaide Underwriters Association Limited (3cm) 10/1S7S Marine Underwriters Association of South Australia Limited (1 file) 20/1SS2 Elder's Wool and Produce Company Limited (Scm) 4/1SS2 Northern Territory Laud Company Limited (4cm) 3/1SSO Executor Trustee & Agency Company of South Australia (Scm) 3/1SSO Executor Trustee & Agency Company of South Australia Limited (1 file) 7/1SS2 Northern Territory Land Company (1 file) 20/1SS2 Elder Smith & Co. -

100 the SOUTH-WEST CORNER of QUEENSLAND. (By S

100 THE SOUTH-WEST CORNER OF QUEENSLAND. (By S. E. PEARSON). (Read at a meeting of the Historical Society of Queensland, August 27, 1937). On a clear day, looking westward across the channels of the Mulligan River from the gravelly tableland behind Annandale Homestead, in south western Queensland, one may discern a long low line of drift-top sandhills. Round more than half the skyline the rim of earth may be likened to the ocean. There is no break in any part of the horizon; not a landmark, not a tree. Should anyone chance to stand on those gravelly rises when the sun was peeping above the eastem skyline they would witness a scene that would carry the mind at once to the far-flung horizons of the Sahara. In the sunrise that western region is overhung by rose-tinted haze, and in the valleys lie the purple shadows that are peculiar to the waste places of the earth. Those naked, drift- top sanddunes beyond the Mulligan mark the limit of human occupation. Washed crimson by the rising sun they are set Kke gleaming fangs in the desert's jaws. The Explorers. The first white men to penetrate that line of sand- dunes, in south-western Queensland, were Captain Charles Sturt and his party, in September, 1845. They had crossed the stony country that lies between the Cooper and the Diamantina—afterwards known as Sturt's Stony Desert; and afterwards, by the way, occupied in 1880, as fair cattle-grazing country, by the Broad brothers of Sydney (Andrew and James) under the run name of Goyder's Lagoon—and the ex plorers actually crossed the latter watercourse with out knowing it to be a river, for in that vicinity Sturt describes it as "a great earthy plain." For forty miles one meets with black, sundried soil and dismal wilted polygonum bushes in a dry season, and forty miles of hock-deep mud, water, and flowering swamp-plants in a wet one. -

Durham Downs — a Pastorale

This is part ofa set Braided Channels Vol 2 Item 4 and may NOT be borrowed separately. Durham Downs — a Pastorale The story of Australia told through the lives of two families, united in their passion for three million acres of land: Durham Downs. 070.18 FITZ [1-2] Concept document produced with the assistance of the Pacific Film and Television Commission and Film Australia. V-------- J > Up* i nfo@jerryca nfi I ms .corn au 32007004706179 PO Box 397 Nth Tambonne Braided channels : QLO 4272 documentary voice from an Ph *61 7 5545 3319 interdiscplinary, Fax +61 7 5545 3349 cross-media, and practitioners's perspective Synopsis Durham Downs - a Pastorale is a 1 x 52 minute documentary that explores the love of land and sense of place that this ancient landscape in far SW Queensland inspires through the story of two families. The film follows the lives of the Ferguson family, retiring managers of Durham Downs Station, as their home passes on to the next family of employees of S. Kidman and Co., the Station’s pastoral lease-holder. As they end a thirty year association with the property and an at least five generations association with the area, the Fergusons are grieving for the loss of their home and trying to make sense of who they will be without Durham Downs. Running in parallel to the Ferguson’s story is that of the Ebsworth family and the Wangkumarra people. Moved from their traditional home in the 1930s, and having worked for the Station over generations, oil and gas exploration of the land is creating new opportunities for them to relate to their land. -

Highways Byways

Highways AND Byways THE ORIGIN OF TOWNSVILLE STREET NAMES Compiled by John Mathew Townsville Library Service 1995 Revised edition 2008 Acknowledgements Australian War Memorial John Oxley Library Queensland Archives Lands Department James Cook University Library Family History Library Townsville City Council, Planning and Development Services Front Cover Photograph Queensland 1897. Flinders Street Townsville Local History Collection, Citilibraries Townsville Copyright Townsville Library Service 2008 ISBN 0 9578987 54 Page 2 Introduction How many visitors to our City have seen a street sign bearing their family name and wondered who the street was named after? How many students have come to the Library seeking the origin of their street or suburb name? We at the Townsville Library Service were not always able to find the answers and so the idea for Highways and Byways was born. Mr. John Mathew, local historian, retired Town Planner and long time Library supporter, was pressed into service to carry out the research. Since 1988 he has been steadily following leads, discarding red herrings and confirming how our streets got their names. Some remain a mystery and we would love to hear from anyone who has information to share. Where did your street get its name? Originally streets were named by the Council to honour a public figure. As the City grew, street names were and are proposed by developers, checked for duplication and approved by Department of Planning and Development Services. Many suburbs have a theme. For example the City and North Ward areas celebrate famous explorers. The streets of Hyde Park and part of Gulliver are named after London streets and English cities and counties. -

List of Deaths.Xlsx

Innamincka Records compiled 2011. Materials supplied b:- SA Genealogy Soc. D Spackman. K Buckley. Office for the Outback Community Authority, Pt Augusta. Surname Given Names Date of Death Sex Age Residence Death Place Burial Place Headstone Innamincka Cemetery Detail Burke Robert O'Hara 1861-06/07-? M 40y Victoria Near Burke Waterhole, Innamincka Melbourne General Cem Memorial Burke's Waterhole Cooper Creek Nr Innamincka Wills William John 1861-06/07-? M 27y Victoria Near Tilcha Waterhole Melbourne General Cem Colless Not Recorded 1880-08-17 F 3h Innamincka Coopers Creek Innamincka Coopers Creek Howard Henry Grenville 1881-11-01 M 50y Innamincka Station Between Mt Lyndhurst and Farina Town Cook. Injuries received thrown from his trap. Cook Richard 1883/4-12-02 M 45y Monta Collina Innamincka Patchewarra Police Mortuary Returns Tee James 1885-05-13 M 37y Farina Innamincka Richards John 1886-02-08 M 61y Innamincka Innamincka Budge John 1887-03-22 M 23y Oonta. Qld Innamincka Dick Samuel 1887-09-07 M 3w Innamincka Innamincka Bronchitis Rowe Thomas Roberts 1888-03-22 M 20y Innamincka Innamincka Labourer. Typhoid Fever. Copp Andrew 1888-05-10 M 37y Innamincka Innamincka Cancer of Throat Melville Not Recorded 1893-07-12 F 36h Innamincka Innamincka Melville Not Recorded 1893-07-12 F 24h Innamincka Innamincka Charley Not Recorded 1893-11-15 M 23y Innamincka Coopers Crk near Lake Hope Aboriginal. Drover.Verdict of Jury -no cause of death McDermott John 1891-07-12 M 36y Innamincka Adelaide Crossman William 1891-08-20 M 30y Nappa Merrie Station Qld Innamincka Station Police Mortuary Returns Bralla William Emanuel 1894-01-23 M 23y Innamincka Station Innamincka Station Innamincka Cemetery photograph 2011 Accidentally drowned Coopers Creek Hampton Edwin John 1894-12-28 M 23y Asbevale Station Qld Innamincka Smith Alick 1895-03-30 M 53y Innamincka Station Innamincka Stockman. -

Cunninghamia : a Journal of Plant Ecology for Eastern Australia

Westbrooke et al., Vegetation of Peery Lake area, western NSW 111 The vegetation of Peery Lake area, Paroo-Darling National Park, western New South Wales M. Westbrooke, J. Leversha, M. Gibson, M. O’Keefe, R. Milne, S. Gowans, C. Harding and K. Callister Centre for Environmental Management, University of Ballarat, PO Box 663 Ballarat, Victoria 3353, AUSTRALIA Abstract: The vegetation of Peery Lake area, Paroo-Darling National Park (32°18’–32°40’S, 142°10’–142°25’E) in north western New South Wales was assessed using intensive quadrat sampling and mapped using extensive ground truthing and interpretation of aerial photograph and Landsat Thematic Mapper satellite images. 378 species of vascular plants were recorded from this survey from 66 families. Species recorded from previous studies but not noted in the present study have been added to give a total of 424 vascular plant species for the Park including 55 (13%) exotic species. Twenty vegetation communities were identified and mapped, the most widespread being Acacia aneura tall shrubland/tall open-shrubland, Eremophila/Dodonaea/Acacia open shrubland and Maireana pyramidata low open shrubland. One hundred and fifty years of pastoral use has impacted on many of these communities. Cunninghamia (2003) 8(1): 111–128 Introduction Elder and Waite held the Momba pastoral lease from early 1870 (Heathcote 1965). In 1889 it was reported that Momba Peery Lake area of Paroo–Darling National Park (32°18’– was overrun by kangaroos (Heathcote 1965). About this time 32°40’S, 142°10’–142°25’E) is located in north western New a party of shooters found opal in the sandstone hills and by South Wales (NSW) 110 km north east of Broken Hill the 1890s White Cliffs township was established (Hardy (Figure 1).