ITALIAN BOOKSHELF Edited by Dino S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Qt2wn8v8p6.Pdf

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Reciprocity in Literary Translation: Gift Exchange Theory and Translation Praxis in Brazil and Mexico (1968-2015) Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2wn8v8p6 Author Gomez, Isabel Cherise Publication Date 2016 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Reciprocity in Literary Translation: Gift Exchange Theory and Translation Praxis in Brazil and Mexico (1968-2015) A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Hispanic Languages and Literatures by Isabel Cherise Gomez 2016 © Copyright by Isabel Cherise Gomez 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Reciprocity in Literary Translation: Gift Exchange Theory and Translation Praxis in Brazil and Mexico (1968-2015) by Isabel Cherise Gomez Doctor of Philosophy in Hispanic Languages and Literatures University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Efraín Kristal, Co-Chair Professor José Luiz Passos, Co-Chair What becomes visible when we read literary translations as gifts exchanged in a reciprocal symbolic economy? Figuring translations as gifts positions both source and target cultures as givers and recipients and supplements over-used translation metaphors of betrayal, plundering, submission, or fidelity. As Marcel Mauss articulates, the gift itself desires to be returned and reciprocated. My project maps out the Hemispheric Americas as an independent translation zone and highlights non-European translation norms. Portuguese and Spanish have been sidelined even from European translation studies: only in Mexico and Brazil do we see autochthonous translation theories in Spanish and Portuguese. Focusing on translation strategies that value ii taboo-breaking, I identify poet-translators in Mexico and Brazil who develop their own translation manuals. -

Creatureliness

Thinking Italian Animals Human and Posthuman in Modern Italian Literature and Film Edited by Deborah Amberson and Elena Past Contents Acknowledgments xi Foreword: Mimesis: The Heterospecific as Ontopoietic Epiphany xiii Roberto Marchesini Introduction: Thinking Italian Animals 1 Deborah Amberson and Elena Past Part 1 Ontologies and Thresholds 1 Confronting the Specter of Animality: Tozzi and the Uncanny Animal of Modernism 21 Deborah Amberson 2 Cesare Pavese, Posthumanism, and the Maternal Symbolic 39 Elizabeth Leake 3 Montale’s Animals: Rhetorical Props or Metaphysical Kin? 57 Gregory Pell 4 The Word Made Animal Flesh: Tommaso Landolfi’s Bestiary 75 Simone Castaldi 5 Animal Metaphors, Biopolitics, and the Animal Question: Mario Luzi, Giorgio Agamben, and the Human– Animal Divide 93 Matteo Gilebbi Part 2 Biopolitics and Historical Crisis 6 Creatureliness and Posthumanism in Liliana Cavani’s The Night Porter and Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Salò 111 Alexandra Hills 7 Elsa Morante at the Biopolitical Turn: Becoming- Woman, Becoming- Animal, Becoming- Imperceptible 129 Giuseppina Mecchia x CONTENTS 8 Foreshadowing the Posthuman: Hybridization, Apocalypse, and Renewal in Paolo Volponi 145 Daniele Fioretti 9 The Postapocalyptic Cookbook: Animality, Posthumanism, and Meat in Laura Pugno and Wu Ming 159 Valentina Fulginiti Part 3 Ecologies and Hybridizations 10 The Monstrous Meal: Flesh Consumption and Resistance in the European Gothic 179 David Del Principe 11 Contemporaneità and Ecological Thinking in Carlo Levi’s Writing 197 Giovanna Faleschini -

Librib 501200.Pdf

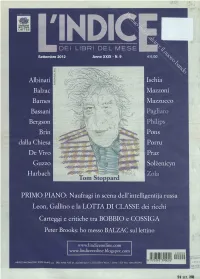

FONDAZIONE BOTTARI LATTES Settembre 2012 Anno XXIX - N. 9 Albinati Ischia Balzac Mazzoni Barnes Mazzucco Bassani Bergson Brin Pons dalla Chiesa Porru De Vivo Praz Guzzo Solzenicyn Harbach PRIMO PIANO: Naufragi in scena del?intelligenti)a russa Leon, Gallino e la LOTTA DI CLASSE dei ricchi Carteggi e critiche tra BOBBIO e COSSIGA Peter Brooks: ho messo BALZAC sul lettino www.lindiceonline.com www.lindiceonline.blogspot.com MENSILE D'INFORMAZIONE - POSTE ITALIANE s.p.a. - SPED. IN ABB. POST. D.L. 353/2003 (conv.in L. 27/02/2004 n° 46) art. I, comma ], DCB Torino - ISSN 0393-3903 Editoria La verità è destabilizzante Per Achille Erba di Lorenzo Fazio Quando è mancato Achille Erba, uno dei fon- ferimento costante al Vaticano II e all'episcopa- a domanda è: "Ma ci quere- spezzarne il meccanismo di pro- datori de "L'Indice", alcune persone a lui vicine to di Michele Pellegrino) sono ampiamente illu- Lleranno?". Domanda sba- duzione e trovare (provare) al- hanno deciso di chiedere ospitalità a quello che lui strate nel sito www.lindiceonline.com. gliata per un editore che si pre- tre verità. Come editore di libri, ha continuato a considerare Usuo giornale - anche È opportuna una premessa. Riteniamo si sarà figge il solo scopo di raccontare opera su tempi lunghi e incrocia quando ha abbandonato l'insegnamento universi- tutti d'accordo che le analisi e le discussioni vol- la verità. Sembra semplice, ep- passato e presente avendo una tario per i barrios di Santiago del Cile e, successi- te ad illustrare e approfondire nei suoi diversi pure tutta la complessità del la- prospettiva anche storica e più vamente, per una vita concentrata sulla ricerca - aspetti la ricerca storica di Achille e ad indivi- voro di un editore di saggistica libera rispetto a quella dei me- allo scopo di convocare un'incontro che ha lo sco- duare gli orientamenti generali che ad essa si col- di attualità sta dentro questa pa- dia, che sono quotidianamente po di ricordarlo, ma anche di avviare una riflessio- legano e che eventualmente la ispirano non pos- rola. -

Bibliografia 2018

BIBLIOGRAFIA 2018 L E G G E R E I L P A E S A G G I O A cura di Fondazione Benetton Studi Ricerche AIB Veneto Leggere per Leggere 1 TERRE ALTE In montagna con l’Orsa Lucia, Antonella Abbatiello, Emme Edizioni BPE Compagno orsetto, Mario Rigoni Stern, Einaudi ragazzi BGE V Milo e il segreto del Karakorum, Enrico Brizzi – Luca Caimmi, Laterza BGE Luì e l’arte di andare nel bosco, Luigi Mainolfi – Guido Quarzo, Hopefulmonster BPE Il bosco racconta, Sabina Colloredo, Einaudi Ragazzi BGE V L’uomo montagna, Séverine Gauthier e Amélie Fléchais, Tunué RGR Il segreto del bosco vecchio, Dino Buzzati, Mondadori RGE V Storie del bosco antico, Mauro Corona, Mondadori RGE V La via di Schenèr, Matteo Melchiorre, Marsilio NGE V Le otto montagne, Paolo Cognetti, Einaudi NGE V Paesi Alti, Antonio G. Bortoluzzi NPE V Neve, cane, piede, Claudio Morandini, Exorma NPE La via del sole, Mauro Corona, Mondadori NGE V Razzo rosso sul Nanga Parbat, Reinhold Messner, Corbaccio NPE Sulla traccia di Nives, Erri De Luca, Feltrinelli NGE Montagne. Avventura, passione, sfida, AA VV, Lit NPE La pelle dell’orso, Matteo Righetto, Guanda NGE V La montagna volante, Christoph Ransmayr, Feltrinelli NGE … E se la vita continua, Cesare Maestri, Dalai NGE Segreto Tibet, Fosco Maraini, Corbaccio CPE La grande parete, Giuseppe Mazzotti, Nuovi Sentieri Editore CPE V Le due chiese, Sebastiano Vassalli, Bur CGE Montagne di una vita, Walter Bonatti, Rizzoli CGE I miracoli di Val Morel, Dino Buzzati, Mondadori CGE V La montagna incantata, Thomas Mann, Corbaccio CPE 2 CHIARE, FRESCHE -

Understanding Poetry Are Combined to Unstressed Syllables in the Line of a Poem

Poetry Elements Sound Includes: ■ In poetry the sound Writers use many elements to create their and meaning of words ■ Rhythm-a pattern of stressed and poems. These elements include: Understanding Poetry are combined to unstressed syllables in the line of a poem. (4th Grade Taft) express feelings, ■ Sound ■ Rhyme-similarity of sounds at the end of thoughts, and ideas. ■ Imagery words. ■ The poet chooses ■ Figurative ■ Alliteration-repetition of consonant sounds at Adapted from: Mrs. Paula McMullen words carefully (Word the beginning of words. Example-Sally sells Language Library Teacher Choice). sea shells Norwood Public Schools ■ Poetry is usually ■ Form ■ Onomatopoeia- uses words that sound like written in lines (not ■ Speaker their meaning. Example- Bang, shattered sentences). 2 3 4 Rhythm Example Rhythm Example Sound Rhythm The Pickety Fence by David McCord Where Are You Now? ■ Rhythm is the flow of the The pickety fence Writers love to use interesting sounds in beat in a poem. The pickety fence When the night begins to fall Give it a lick it's their poems. After all, poems are meant to ■ Gives poetry a musical And the sky begins to glow The pickety fence You look up and see the tall be heard. These sound devices include: feel. Give it a lick it's City of lights begin to grow – ■ Can be fast or slow, A clickety fence In rows and little golden squares Give it a lick it's a lickety fence depending on mood and The lights come out. First here, then there ■ Give it a lick Rhyme subject of poem. -

Between the Local and the National: the Free Territory of Trieste, "Italianita," and the Politics of Identity from the Second World War to the Osimo Treaty

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2014 Between the Local and the National: The Free Territory of Trieste, "Italianita," and the Politics of Identity from the Second World War to the Osimo Treaty Fabio Capano Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Capano, Fabio, "Between the Local and the National: The Free Territory of Trieste, "Italianita," and the Politics of Identity from the Second World War to the Osimo Treaty" (2014). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 5312. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/5312 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Between the Local and the National: the Free Territory of Trieste, "Italianità," and the Politics of Identity from the Second World War to the Osimo Treaty Fabio Capano Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Modern Europe Joshua Arthurs, Ph.D., Co-Chair Robert Blobaum, Ph.D., Co-Chair Katherine Aaslestad, Ph.D. -

Brochure Lignano Eng

Seaside holidays with a difference A melting pot for Latin, Germanic and Slav civilizations. Beaches of fine sand and a sea gently sloping away in Lignano and Grado, inlets embedded between white rocks in Trieste. Enchanting places, all year round. espite its limited extension, the And the allure of this area lasts well D coastline of Friuli Venezia Giulia beyond the summer months. offers many different facets of typical The fascination of Friuli Venezia Giulia Mediterranean appeal: surroundings and coast is just as intense in the spring, landscapes that astonish visitors because autumn and even winter. Mediterranean of the incredible contrasts in the space This is when the beaches are ideal for of a few miles. long romantic strolls. Grado is animated This is right where the Adriatic laps at by its centuries-old fishing tradition, with the shores of central Europe, offering delicious freshly caught fish skilfully a meeting between Latin, Germanic prepared by the local restaurants. and Slavic Mediterranean cultures. Northwards, the Trieste gulf, swept beaches From Lignano Sabbiadoro to Grado, the frequently by the impetuous north-easterly Friuli Venezia Giulia coast welcomes you Bora wind, offers a more introspective with its inviting and relaxing appeal. relationship with the sea. Here you’ll find broad sandy beaches From Duino to Sistiana and through to with their characteristic soft golden-brown Trieste itself, the coastline features a coloured sand and dunes. succession of sheer white cliffs interspersed in the heart And the sea is absolutely irresistible, with areas of dense Mediterranean vegetation. with its shallow waters and relaxing waves It’s also an ideal destination for summer that break gently on the beach. -

UNIVERSITE PARIS OUEST NANTERRE LA DÉFENSE UNIVERSITE DE VARSOVIE Doctorat Etudes Italiennes

UNIVERSITE PARIS OUEST NANTERRE LA DÉFENSE UNIVERSITE DE VARSOVIE Ecole Doctorale 138 Lettres, Langues, Spectacles Doctorat Etudes Italiennes - Littérature Italienne Tomasz Skocki Memoria delle colonie e postcolonialismo nella letteratura italiana contemporanea Thèse dirigée par Mme Silvia Contarini (Université Paris Ouest Nanterre la Défense) Mme Hanna Serkowska (Université de co-tutelle) Soutenue le 02 juin 2014 Sommario Introduzione p. 1 Capitolo I: Il colonialismo italiano tra storia e letteratura p. 7 1. La problematica storica del colonialismo italiano p. 7 2. Le prime iniziative coloniali in Africa Orientale p. 15 3. L’occupazione della Libia p. 21 4. La guerra d’Abissinia e l’impero p. 24 5. Atrocità e violenze del colonialismo italiano p. 30 6. Italia e colonie nel secondo dopoguerra p. 34 7. Le ex-colonie l’Italia tra secondo Novecento e nuovo millennio p. 38 8. Il colonialismo nella letteratura e cultura italiana fino alla Seconda p. 41 guerra mondiale 9. La letteratura del secondo dopoguerra e il caso di Ennio Flaiano p. 57 Capitolo II: Letterature e studi postcoloniali nel mondo e in Italia p. 65 1. Studi e letterature postcoloniali nella cultura contemporanea p. 65 2. Sfide al canone e riscritture nella letteratura postcoloniale anglofoba p. 79 3. Studi postcoloniali, studi subalterni, studi culturali p. 86 4. Tematiche coloniali nella letteratura italiana del secondo Novecento p. 89 5. Letteratura migrante e postcoloniale nell’Italia contemporanea p. 98 6. Letteratura italiana del XXI secolo e memoria (post)coloniale p. 103 7. Temi e problematiche postcoloniali in Italia p. 106 Capitolo III: Il colonialismo come violenza p. -

NUMERO 23, NOVEMBRE 2020: Metamorfosi Dell’Antico

NUMERO 23, NOVEMBRE 2020: Metamorfosi dell’antico Editoriale di Stefano Salvi e Italo Testa 3 IL DIBATTITO Francesco Ottonello, Francesca Mazzotta, Buffoni tra metamorfosi e epifanie 539 Ecloga virgiliana tra Auden e Zanzotto 286 Giuseppe Nibali, ANTICHI MAESTRI NEL SECONDO Il tragico in Combattimento ininterrotto NOVECENTO di Ceni 550 Enrico Tatasciore, ALTRI SGUARDI Gianluca Fùrnari, Il Ganimede e il Narciso di Saba 7 Poesia neolatina nell’ultimo trentennio 556 Paolo Giovannetti, Antonio Sichera, Francesco Ottonello, Whitman secondo P. Jannaccone 303 Il mito in Lavorare stanca 1936 di Pavese 49 Anedda tra sardo e latino 584 Carlotta Santini, Francesco Capello, Italo Testa, La perduta città di Wagadu 310 Fantasie fusionali e trauma in Pavese 58 Bifarius, o della Ninfa di Vegliante 591 Valentina Mele, Gian Mario Anselmi, Michele Ortore, Il Cavalcanti di Pound 326 Pasolini: mito e senso del sacro 96 La costanza dell’antico nella poesia di A. Ricci 597 Mariachiara Rafaiani, Pietro Russo, Antonio Devicienti, Nella Bann Valley di Heaney 339 Odissea e schermi danteschi in Sereni 100 Il sogno di Giuseppe di S. Raimondi 611 Tommaso Di Dio, Massimiliano Cappello, Orfeo in Ashbery, Bandini e Anedda 350 Alcuni epigrammi di Giudici 109 Salvatore Renna, Filomena Giannotti, Mito e suicidio in Eugenides e Kane 376 L’Enea ritrovato in un dattiloscritto di Caproni 122 Vassilina Avramidi, Alessandra Di Meglio, L’Odissea ‘inclusiva’ di Emily Wilson 391 Il bipolarismo d’Ottieri tra Africa e Milano 138 Chiara Conterno, Marco Berisso, Lo Shofar nella lirica -

De Duarte Nunes De Leão

ORTÓGRAFOS PORTUGUESES 2 CENTRO DE ESTUDOS EM LETRAS UNIVERSIDADE DE TRÁS-OS-MONTES E ALTO DOURO Carlos Assunção, Rolf Kemmler, Gonçalo Fernandes, Sónia Coelho, Susana Fontes, Teresa Moura (1576) de Duarte Nunes de Leão A ORTHOGRAPHIA DA LINGOA PORTVGVESA (1576) DE DUARTE NUNES DE LEÃO Orthographia da Lingoa Portvgvesa Orthographia A Estudo introdutório e edição Coelho, Fontes, Moura Coelho, Fontes, Assunção, Kemmler, Fernandes, Fernandes, Assunção, Kemmler, 2 VILA REAL - MMX I X Carlos Assunção, Rolf Kemmler, Gonçalo Fernandes, Sónia Coelho, Susana Fontes, Teresa Moura A ORTHOGRAPHIA DA LINGOA PORTVGVESA (1576) DE DUARTE NUNES DE LEÃO ESTUDO INTRODUTÓRIO E EDIÇÃO COLEÇÃO ORTÓGRAFOS PORTUGUESES 2 CENTRO DE ESTUDOS EM LETRAS UNIVERSIDADE DE TRÁS-OS-MONTES E ALTO DOURO VILA REAL • MMXIX Autores: Carlos Assunção, Rolf Kemmler, Gonçalo Fernandes, Sónia Coelho, Susana Fontes, Teresa Moura Título: A Orthographia da Lingoa Portvgvesa (1576) de Duarte Nunes de Leão: Estudo introdutório e edição Coleção: ORTÓGRAFOS PORTUGUESES 2 Edição: Centro de Estudos em Letras / Universidade de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro, Vila Real, Portugal ISBN: 978-989-704-388-8 e-ISBN: 978-989-704-389-5 Publicação: 27 de dezembro de 2019 Índice Prefácio ................................................................................................ V Estudo introdutório: 1 Duarte Nunes de Leão, o autor e a obra ................................................................ VII 1.1 Duarte Nunes de Leão (ca. 1530-1608): breve resenha biográfica ................................VII -

Robert O. Paxton-The Anatomy of Fascism -Knopf

Paxt_1400040949_8p_all_r1.qxd 1/30/04 4:38 PM Page b also by robert o. paxton French Peasant Fascism Europe in the Twentieth Century Vichy France: Old Guard and New Order, 1940–1944 Parades and Politics at Vichy Vichy France and the Jews (with Michael R. Marrus) Paxt_1400040949_8p_all_r1.qxd 1/30/04 4:38 PM Page i THE ANATOMY OF FASCISM Paxt_1400040949_8p_all_r1.qxd 1/30/04 4:38 PM Page ii Paxt_1400040949_8p_all_r1.qxd 1/30/04 4:38 PM Page iii THE ANATOMY OF FASCISM ROBERT O. PAXTON Alfred A. Knopf New York 2004 Paxt_1400040949_8p_all_r1.qxd 1/30/04 4:38 PM Page iv this is a borzoi book published by alfred a. knopf Copyright © 2004 by Robert O. Paxton All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Distributed by Random House, Inc., New York. www.aaknopf.com Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc. isbn: 1-4000-4094-9 lc: 2004100489 Manufactured in the United States of America First Edition Paxt_1400040949_8p_all_r1.qxd 1/30/04 4:38 PM Page v To Sarah Paxt_1400040949_8p_all_r1.qxd 1/30/04 4:38 PM Page vi Paxt_1400040949_8p_all_r1.qxd 1/30/04 4:38 PM Page vii contents Preface xi chapter 1 Introduction 3 The Invention of Fascism 3 Images of Fascism 9 Strategies 15 Where Do We Go from Here? 20 chapter 2 Creating Fascist Movements 24 The Immediate Background 28 Intellectual, Cultural, and Emotional -

Report of the Twentieh Session of the Committee on Fisheries. Rome, 15

FAO Fisheries Report No. 488 FIPL/R488 ISSN 0429-9337 Report of the TWENTIETH SESSION OF THE COMMITTEE ON FISHERIES Rome, 15-19 March 1993 FO,' FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS 1r FAO Fisheries Report No 488 2Lf REPORT OF THE TWENTIETH SESSION OF THE COMMITTEE ON FISHERIES Rome, 15-19 March 1993 FOOD I,AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF INAT]Í NS Rome 1993 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever ori the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. M-40 ISBN 925-1 03399-4 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, rnechani- cal, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Applications for such permission, with a statement of the purpose and extent of the reproduction, should be addressed to the Director, Publications Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00100 Rome, Italy. © FAO 1993 PREPARATION OF THIS REPORT This is the final version of the report as approved by the Twentieth Session of the Committee on Fisheries. Distribution: All FAO Member Nations and Associate Members Participants in the session Other interested Nations and International Organizations FAO Fisheries Department Fishery Officers in FAO Regional Offices - iv - FAO Report of the twentieth session of the Committee on Fisheries.