Josefa De Ayala (1630-1684)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interiors and Interiority in Vermeer: Empiricism, Subjectivity, Modernism

ARTICLE Received 20 Feb 2017 | Accepted 11 May 2017 | Published 12 Jul 2017 DOI: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.68 OPEN Interiors and interiority in Vermeer: empiricism, subjectivity, modernism Benjamin Binstock1 ABSTRACT Johannes Vermeer may well be the foremost painter of interiors and interiority in the history of art, yet we have not necessarily understood his achievement in either domain, or their relation within his complex development. This essay explains how Vermeer based his interiors on rooms in his house and used his family members as models, combining empiricism and subjectivity. Vermeer was exceptionally self-conscious and sophisticated about his artistic task, which we are still laboring to understand and articulate. He eschewed anecdotal narratives and presented his models as models in “studio” settings, in paintings about paintings, or art about art, a form of modernism. In contrast to the prevailing con- ception in scholarship of Dutch Golden Age paintings as providing didactic or moralizing messages for their pre-modern audiences, we glimpse in Vermeer’s paintings an anticipation of our own modern understanding of art. This article is published as part of a collection on interiorities. 1 School of History and Social Sciences, Cooper Union, New York, NY, USA Correspondence: (e-mail: [email protected]) PALGRAVE COMMUNICATIONS | 3:17068 | DOI: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.68 | www.palgrave-journals.com/palcomms 1 ARTICLE PALGRAVE COMMUNICATIONS | DOI: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.68 ‘All the beautifully furnished rooms, carefully designed within his complex development. This essay explains how interiors, everything so controlled; There wasn’t any room Vermeer based his interiors on rooms in his house and his for any real feelings between any of us’. -

O Arquivo Pessoal De Irene Quilhó Dos Santos Anexos

UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE BELAS-ARTES O ARQUIVO PESSOAL DE IRENE QUILHÓ DOS SANTOS Tratamento documental ANEXOS Melissa Nogueira de Queiroz Trabalho de Projeto Mestrado em Museologia e Museografia Trabalho de Projeto orientado pelo Prof. Doutor Eduardo Duarte 2019 Anexo 1 - Folha de registo do X-Arq Anexo 2 –Registo completo no X-Arq Web de um documento simples Exemplo representado no quadro de classificação Anexo 3 – Disponibilização pública através do X-Arq Web Anexo 4 – Acondicionamento dos documentos. Capilhas Câmara Municipal de Cascais PT/CMC-CRSIQS/IQ/A/001/003 Subentidade CRSIQS Casa Reynaldo dos Santos/Irene Quilhó dos Santos detentora Fundo IQ Irene Quilhó dos Santos Secção A Biografia Série 001 Documentos Pessoais Subsérie 003 Assentos e Certidões Nº Inv 001 Data 1933 - 2004 Nº documentos 8 Âmbito e conteúdo Anexo 5 – Arquivo Pessoal de Irene Quilhó dos Santos: Inventários Recortes de Imprensa Série 001 Data de Estado de Nº Inv. Título Autor Jornal Páginas Nº folhas Assunto / Observações Dimensões Descritores publicação Conservação Celebração do matrimónio entre Cândido Augusto de Abreu Santos e D. Maria Irene Virote. Indicação de que a noiva era filha do soldado da República José de Souza Virote e também mãe de Irene Virote Quilhó. Virote, Maria Irene; Santos, Cândido Augusto RI-001 "Casamento" Jornal República 1912-02-08 3 1 Destaque num trecho do respetivo artigo através de caneta Mau 57,5 x 41,3 cm de Abreu; Casamento esferográfica azul e verifica-se o seguinte apontamento manuscrito: “Jornal do dia 8-2-1912 (dia seguinte ao meu casamento, casei-me em 7-2-1912)”. -

Dois Arquivos Científicos Existentes Na Casa Reynaldo Dos Santos Irene Quilhó Dos Santos, Município De Cascais

Título da comunicação: Dois arquivos científicos existentes na Casa Reynaldo dos Santos Irene Quilhó dos Santos, Município de Cascais. Resumo: Pretende-se, com esta comunicação, dar a conhecer dois Arquivos Científicos que integram a Casa Reynaldo dos Santos Irene Quilhó dos Santos, na Parede, doada por Irene Quilhó ao Município de Cascais. O Arquivo pessoal do Prof. Reynaldo dos Santos reveste-se de grande importância para a história da medicina em Portugal, nomeadamente no que toca à Urologia e Arteriografia, à reestruturação dos serviços médicos e hospitalares e ao ensino da medicina em Portugal. Os seus apontamentos de trabalho, aliados às fichas de doentes, a correspondência com outros cientistas nacionais e internacionais, complementam a área clínica e docente, revestindo este espólio de importante valor para a compreensão e contextualização da medicina e da vida social e cultural na primeira metade do século XX português. Reynaldo dos Santos, 1880-1970, após a licenciatura em medicina estagiou em Paris em 1903 e, em 1905, fez um périplo nos EUA onde visitou clínicas em Boston, Chicago, Rochester, Baltimore, Filadélfia e Nova Iorque e criou laços de amizade com Alexis Carrel, Harvey Cushing, Rudolph Matas, entre outros. Concluiu o doutoramento em 1906 e iniciou a docência na Faculdade de Medicina de Lisboa. Em 1910 preparou um Curso Livre de Urologia no Hospital do Desterro, onde introduziu a urorritmografia. Nos vários estágios realizados entre 1909 e 1914, passou por Berlim, Kummel, Veneza, Viena de Áustria, Londres, Hamburgo, Bremen, Bona e Bruxelas, países que mais tarde o homenagearam com as mais altas condecorações. Pertenceu ao CEP (Corpo Expedicionário Português) na 1ª Grande Guerra onde desempenhou missões do Governo junto dos exércitos aliados, foi membro do Comité Interaliado para o estudo da Cirurgia de Guerra e consultor de cirurgia do CEP. -

The Collecting, Dealing and Patronage Practices of Gaspare Roomer

ART AND BUSINESS IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY NAPLES: THE COLLECTING, DEALING AND PATRONAGE PRACTICES OF GASPARE ROOMER by Chantelle Lepine-Cercone A thesis submitted to the Department of Art History In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (November, 2014) Copyright ©Chantelle Lepine-Cercone, 2014 Abstract This thesis examines the cultural influence of the seventeenth-century Flemish merchant Gaspare Roomer, who lived in Naples from 1616 until 1674. Specifically, it explores his art dealing, collecting and patronage activities, which exerted a notable influence on Neapolitan society. Using bank documents, letters, artist biographies and guidebooks, Roomer’s practices as an art dealer are studied and his importance as a major figure in the artistic exchange between Northern and Sourthern Europe is elucidated. His collection is primarily reconstructed using inventories, wills and artist biographies. Through this examination, Roomer emerges as one of Naples’ most prominent collectors of landscapes, still lifes and battle scenes, in addition to being a sophisticated collector of history paintings. The merchant’s relationship to the Spanish viceregal government of Naples is also discussed, as are his contributions to charity. Giving paintings to notable individuals and large donations to religious institutions were another way in which Roomer exacted influence. This study of Roomer’s cultural importance is comprehensive, exploring both Northern and Southern European sources. Through extensive use of primary source material, the full extent of Roomer’s art dealing, collecting and patronage practices are thoroughly examined. ii Acknowledgements I am deeply thankful to my thesis supervisor, Dr. Sebastian Schütze. -

Cultura, Vol. 21 | 2005 Poder De Convencimento E Narração Imagética Na Pintura Portuguesa Da Contra-R

Cultura Revista de História e Teoria das Ideias vol. 21 | 2005 Livro e Iconografia Poder de convencimento e narração imagética na pintura portuguesa da contra-reforma A influência de um gravado segundo Seghers numa tela do Convento dos Paulistas de Portel The power of persuasion and images narrative in counter-reformation Portuguese painting: the influente of an engraving following Seghers in a canvas of the Paulistas Monastery at Portel Vítor Serrão Edição electrónica URL: http://journals.openedition.org/cultura/2951 DOI: 10.4000/cultura.2951 ISSN: 2183-2021 Editora Centro de História da Cultura Edição impressa Data de publição: 1 Janeiro 2005 Paginação: 65-76 ISSN: 0870-4546 Refêrencia eletrónica Vítor Serrão, « Poder de convencimento e narração imagética na pintura portuguesa da contra- reforma », Cultura [Online], vol. 21 | 2005, posto online no dia 26 maio 2016, consultado a 21 abril 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/cultura/2951 ; DOI : 10.4000/cultura.2951 Este documento foi criado de forma automática no dia 21 Abril 2019. © CHAM — Centro de Humanidades / Centre for the Humanities Poder de convencimento e narração imagética na pintura portuguesa da contra-r... 1 Poder de convencimento e narração imagética na pintura portuguesa da contra-reforma A influência de um gravado segundo Seghers numa tela do Convento dos Paulistas de Portel The power of persuasion and images narrative in counter-reformation Portuguese painting: the influente of an engraving following Seghers in a canvas of the Paulistas Monastery at Portel Vítor Serrão 1. A História da Arte reconhece hoje o papel muito destacado que foi assumido pela imagem gravada nos sucessivos processos de evolução artística. -

Julius S. Held Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3g50355c No online items Finding aid for the Julius S. Held papers, ca. 1921-1999 Isabella Zuralski. Finding aid for the Julius S. Held 990056 1 papers, ca. 1921-1999 Descriptive Summary Title: Julius S. Held papers Date (inclusive): ca. 1918-1999 Number: 990056 Creator/Collector: Held, Julius S (Julius Samuel) Physical Description: 168 box(es)(ca. 70 lin. ft.) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Research papers of Julius Samuel Held, American art historian renowned for his scholarship in 16th- and 17th-century Dutch and Flemish art, expert on Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. The ca. 70 linear feet of material, dating from the mid-1920s to 1999, includes correspondence, research material for Held's writings and his teaching and lecturing activities, with extensive travel notes. Well documented is Held's advisory role in building the collection of the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico. A significant portion of the ca. 29 linear feet of study photographs documents Flemish and Dutch artists from the 15th to the 17th century. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English Biographical / Historical Note The art historian Julius Samuel Held is considered one of the foremost authorities on the works of Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. -

Review of Vermeer and the Art of Painting, by Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College History of Art Faculty Research and Scholarship History of Art 1997 Review of Vermeer and the Art of Painting, by Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr. Christiane Hertel Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Custom Citation Hertel, Christiane. Review of Vermeer and the Art of Painting, by Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr. Renaissance Quarterly 50 (1997): 329-331, doi: 10.2307/3039381. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs/2 For more information, please contact [email protected]. REVIEWS 329 Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr. Vermeer of paintlayers, x-rays, collaged infrared and the Art of Painting. New Ha- reflectograms,and lab reports - to ven and London: Yale University guide the readerthrough this process. Press, 1995. 143 pls. + x + 201 pp. The pedagogicand rhetorical power of $45. Wheelock's account lies in the eye- This book about Vermeer'stech- openingskill with which he makesthis nique of paintingdiffers from the au- processcome alivefor the reader.The thor'searlier work on the artistby tak- way he accomplishesthis has every- ing a new perspectiveboth on Vermeer thingto do with his convictionthat by as painterand on the readeras viewer. understandingVermeer's artistic prac- Wheelockinvestigates Vermeer's paint- tice we also come to know the artist. ing techniquesin orderto understand As the agentof this practiceVermeer is his artisticpractice and, ultimately, his alsothe grammaticalsubject of most of artisticmind. -

Cna85b2317313.Pdf

THE PAINTERS OF THE SCHOOL OF FERRARA BY EDMUND G. .GARDNER, M.A. AUTHOR OF "DUKES AND POETS IN FERRARA" "SAINT CATHERINE OF SIENA" ETC LONDON : DUCKWORTH AND CO. NEW YORK : CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS I DEDICATE THIS BOOK TO FRANK ROOKE LEY PREFACE Itf the following pages I have attempted to give a brief account of the famous school of painting that originated in Ferrara about the middle of the fifteenth century, and thence not only extended its influence to the other cities that owned the sway of the House of Este, but spread over all Emilia and Romagna, produced Correggio in Parma, and even shared in the making of Raphael at Urbino. Correggio himself is not included : he is too great a figure in Italian art to be treated as merely the member of a local school ; and he has already been the subject of a separate monograph in this series. The classical volumes of Girolamo Baruffaldi are still indispensable to the student of the artistic history of Ferrara. It was, however, Morelli who first revealed the importance and significance of the Perrarese school in the evolution of Italian art ; and, although a few of his conclusions and conjectures have to be abandoned or modified in the light of later researches and dis- coveries, his work must ever remain our starting-point. vii viii PREFACE The indefatigable researches of Signor Adolfo Venturi have covered almost every phase of the subject, and it would be impossible for any writer now treating of Perrarese painting to overstate the debt that he must inevitably owe to him. -

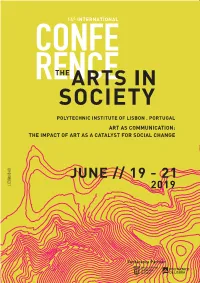

Art As Communication: Y the Impact of Art As a Catalyst for Social Change Cm

capa e contra capa.pdf 1 03/06/2019 10:57:34 POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE OF LISBON . PORTUGAL C M ART AS COMMUNICATION: Y THE IMPACT OF ART AS A CATALYST FOR SOCIAL CHANGE CM MY CY CMY K Fifteenth International Conference on The Arts in Society Against the Grain: Arts and the Crisis of Democracy NUI Galway Galway, Ireland 24–26 June 2020 Call for Papers We invite proposals for paper presentations, workshops/interactive sessions, posters/exhibits, colloquia, creative practice showcases, virtual posters, or virtual lightning talks. Returning Member Registration We are pleased to oer a Returning Member Registration Discount to delegates who have attended The Arts in Society Conference in the past. Returning research network members receive a discount o the full conference registration rate. ArtsInSociety.com/2020-Conference Conference Partner Fourteenth International Conference on The Arts in Society “Art as Communication: The Impact of Art as a Catalyst for Social Change” 19–21 June 2019 | Polytechnic Institute of Lisbon | Lisbon, Portugal www.artsinsociety.com www.facebook.com/ArtsInSociety @artsinsociety | #ICAIS19 Fourteenth International Conference on the Arts in Society www.artsinsociety.com First published in 2019 in Champaign, Illinois, USA by Common Ground Research Networks, NFP www.cgnetworks.org © 2019 Common Ground Research Networks All rights reserved. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the applicable copyright legislation, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the publisher. For permissions and other inquiries, please visit the CGScholar Knowledge Base (https://cgscholar.com/cg_support/en). -

Rembrandt: the Denial of Peter

http://www.amatterofmind.us/ PIERRE BEAUDRY’S GALACTIC PARKING LOT REMBRANDT: THE DENIAL OF PETER How an artistic composition reveals the essence of an axiomatic moment of truth By Pierre Beaudry, 9/23/16 Figure 1 Rembrandt (1606-1669), The Denial of Peter, (1660) Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Page 1 of 14 http://www.amatterofmind.us/ PIERRE BEAUDRY’S GALACTIC PARKING LOT INTRODUCTION: A PRAYER ON CANVAS All four Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John have reported on the prediction that Jesus made during the Last Supper, stating that Peter would disown him three times before the night was over, and all four mentioned the event of that denial in one form or another. If ever there was a religious subject that was made popular for painters in the Netherlands during the first half of the seventeenth century, it was the denial of Peter. More than twenty European artists of that period, most of them were Dutch, chose to depict the famous biblical scene, but none of them touched on the subject in the profound axiomatic manner that Rembrandt did. Rembrandt chose to go against the public opinion view of Peter’s denial and addressed the fundamental issue of the axiomatic change that takes place in the mind of an individual at the moment when he is confronted with the truth of having to risk his own life for the benefit of another. This report has three sections: 1. THE STORY OF THE NIGHT WHEN PETER’S LIFE WAS CHANGED 2. THE TURBULENT SENSUAL NOISE BEHIND THE DIFFERENT POPULAR PAINTINGS OF PETER’S DENIAL 3. -

The Domestication of History in American Art: 1848-1876

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1998 The domestication of history in American art: 1848-1876 Jochen Wierich College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Wierich, Jochen, "The domestication of history in American art: 1848-1876" (1998). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623945. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-qc92-2y94 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

HNA Apr 2015 Cover.Indd

historians of netherlandish art NEWSLETTER AND REVIEW OF BOOKS Dedicated to the Study of Netherlandish, German and Franco-Flemish Art and Architecture, 1350-1750 Vol. 32, No. 1 April 2015 Peter Paul Rubens, Agrippina and Germanicus, c. 1614, oil on panel, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Andrew W. Mellon Fund, 1963.8.1. Exhibited at the Academy Art Museum, Easton, MD, April 25 – July 5, 2015. HNA Newsletter, Vol. 23, No. 2, November 2006 1 historians of netherlandish art 23 S. Adelaide Avenue, Highland Park, NJ 08904 Telephone: (732) 937-8394 E-Mail: [email protected] www.hnanews.org Historians of Netherlandish Art Offi cers President – Amy Golahny (2013-2017) Lycoming College Williamsport PA 17701 Vice-President – Paul Crenshaw (2013-2017) Providence College Department of Art History 1 Cummingham Square Providence RI 02918-0001 Treasurer – Dawn Odell Lewis and Clark College 0615 SW Palatine Hill Road Portland OR 97219-7899 European Treasurer and Liaison - Fiona Healy Seminarstrasse 7 D-55127 Mainz Germany Contents Board Members President's Message .............................................................. 1 Obituary/Tributes ................................................................. 1 Lloyd DeWitt (2012-2016) Stephanie Dickey (2013-2017) HNA News ............................................................................7 Martha Hollander (2012-2016) Personalia ............................................................................... 8 Walter Melion (2014-2018) Exhibitions ...........................................................................