New Testament Translations from the Cairo Genizah∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toolkit for Genizah Scholars: a Practical Guide for Neophytes

EAJS SUMMER LABORATORY FOR YOUNG GENIZAH RESEARCHERS Institut für den Nahen und Mittleren Osten, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, München, 6–7 September 2017 Toolkit for Genizah Scholars: A Practical Guide for Neophytes Compiled by Gregor Schwarb (SOAS, University of London) A) Introductory articles, general overviews, guides and basic reference works: Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2nd edition, vol. 16, cols. 1333–42 [http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/genizah- cairo]. Stefan REIF et al., “Cairo Geniza”, in The Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World, vol. 1, ed . N. Stillman, Leiden: Brill, 2010, pp. 534–555. Nehemya ALLONY, The Jewish Library in the Middle Ages: Book Lists from the Cairo Genizah, ed. Miriam FRENKEL and Haggai BEN-SHAMMAI with the participation of Moshe SOKOLOW, Jerusalem: Ben-Zvi Institute, 2006 [Hebrew]. An update of JLMA, which will include additional book lists and inventories from the Cairo Genizah, is currently being prepared. Haggai BEN-SHAMMAI, “Is “The Cairo Genizah” a Proper Name or a Generic Noun? On the Relationship between the Genizot of the Ben Ezra and the Dār Simḥa Synagogues”, in “From a Sacred Source”: Genizah Studies in Honour of Professor Stefan C. Reif, ed. Ben Outhwaite and Siam Bhayro, Leiden: Brill, 2011, pp. 43–52. Rabbi Mark GLICKMAN, Sacred Treasure: The Cairo Genizah. The Amazing Discoveries of Forgotten Jewish History in an Egyptian Synagogue Attic, Woodstock: Jewish Lights Publishing, 2011. Adina HOFFMAN and Peter COLE, Sacred Trash: The Lost and Found World of the Cairo Geniza, New York: Nextbook, Schocken, 2010. Simon HOPKINS, “The Discovery of the Cairo Geniza”, in Bibliophilia Africana IV (Cape Town 1981). -

1 Between Egypt and Yemen in the Cairo Genizah Amir Ashur Center

Between Egypt and Yemen in the Cairo Genizah Amir Ashur Center for the Study of Conversion and Inter-religious Encounters, Ben Gurion University, the Interdisciplinary Center for the Broader Application of Genizah Research, University of Haifa, and the Department of Hebrew Culture, Tel Aviv University [email protected] Ben Outhwaite University of Cambridge [email protected] Abstract A study of two documents from the Cairo Genizah, a vast repository of medieval Jewish writings recovered from a synagogue in Fusṭāṭ, Egypt, one hundred years ago, shows the importance of this archive for the history of medieval Yemen and, in particular, for the role that Yemen played in the Indian Ocean trade as both a commercial and administrative hub. The first document is a letter from Aden to Fusṭāṭ, dated 1133 CE, explaining the Aden Jewish community’s failure to raise funds to send to the heads of the Palestinian Gaonate in Egypt. It signals the decline of that venerable institution and the increasing independence of the Yemeni Jews. The second text is a legal document, produced by an Egyptian Jewish trader who intended to travel to Yemen, but who wished to ensure his wife was provided for in his absence. Both documents show the close ties between the Egyptian and Yemeni Jewish communities and the increasing commercial importance of Yemen to Egyptian traders. Keywords Cairo Genizah, history, India trade, al-Ǧuwwa, Hebrew, Judaeo- Arabic, marriage, Jewish leadership, legal contract, Aden, Fusṭāṭ. 1. Introduction The discovery of a vast store of manuscripts and early printed material in the Ben Ezra Synagogue in Fusṭāṭ at the end of the nineteenth century revolutionised the academic study of Judaism and provided a wealth of primary sources for the scrutiny of the Mediterranean world at large in the High Middle Ages and Early Modern period. -

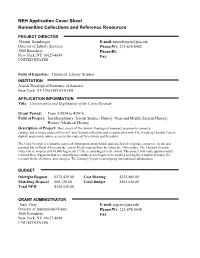

NEH Application Cover Sheet Humanities Collections and Reference Resources

NEH Application Cover Sheet Humanities Collections and Reference Resources PROJECT DIRECTOR Naomi Steinberger E-mail:[email protected] Director of Library Services Phone(W): 212-678-8982 3080 Broadway Phone(H): New York, NY 10027-4649 Fax: UNITED STATES Field of Expertise: Technical: Library Science INSTITUTION Jewish Theological Seminary of America New York, NY UNITED STATES APPLICATION INFORMATION Title: Conservation and Digitization of the Cairo Genizah Grant Period: From 5/2014 to 4/2016 Field of Project: Interdisciplinary: Jewish Studies; History: Near and Middle Eastern History; History: Medieval History Description of Project: The Library of The Jewish Theological Seminary proposes to conserve, catalog, and re-house material from its Cairo Genizah collection and, in partnership with The Friedberg Genizah Project, digitize and provide online access to this material for scholars and the public. The Cairo Genizah is a valuable source of information about Jewish and non-Jewish religious, economic, social, and personal life in North Africa and the eastern Mediterranean from the 9th to the 19th century. The Library's Genizah collection is comprised of 43,000 fragments ??? the second-largest in the world. This project will make approximately 6,000 of these fragments that are currently unreadable or too fragile to be handled and digitized widely available for research for the first time, and complete The Library???s part in an ongoing international collaboration. BUDGET Outright Request $272,429.00 Cost Sharing $222,469.00 Matching Request $68,120.00 Total Budget $563,018.00 Total NEH $340,549.00 GRANT ADMINISTRATOR Josie Gray E-mail:[email protected] Director of Institutional Grants Phone(W): 212-678-8048 3080 Broadway Fax: New York, NY 10027-4649 UNITED STATES The Library of The Jewish Theological Seminary Application to NEH Division of Preservation and Access, HCRR Program, July 2013 Implementation Grant for Conservation and Digitization of the Cairo Genizah 1. -

Martinez, Florentino Garcia. the Dead Sea Scrolls Translated: the Qumran Texts in English

Prof. Scott B. Noegel Chair, Dept. of Near Eastern Languages and Civilization University of Washington Book review: Martinez, Florentino Garcia. The Dead Sea Scrolls Translated: The Qumran Texts in English. Wilfred G. E. Watson, trans. Leiden: E.}. Brill, 1994. First Published in: Digest of Middle Eastern Studies 4/4 (1995), 78-85. ~ ) j"a{{1995 ~ ~ 'Roo(~aT/{{%anllscn'pts the more cumbersome scholarly sigla of the officinl publicntion. While the author admits that the lack of notes potentinlly could prevent the student from grasping "the literary, historical, and theological problems" (p. xxviii) which the scrolls present, the benefits ofthis volume to the interested reader will outweigh by far he Dead Sea Scrolls Translated: any drawbacks. Other English versions ofthe seroUspale in compar- The Qumran Texts in English ison (cf. the now out.of-date Gaster [1956] and the incomplete T Vermes [1995J,the latter ofwhich translates only 70 manuscripts). This book has many positive attributes. The line numbering Florentino Garcia Martinez informs the reader exactly where words appear in the texts. In addition, we may thank Martinez for keeping restorations to a Translated by Wilfred G. E. Watson minimum, despite the fragmentary nature of many of the scrolls. Excessive restoration of any ancient text almost always leads to a Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1994,lxvii, 513 pages. $80 cloth misunderstanding of that text. Compare, for example, the recent (ISBN 90-04-10088-1), $30 paperback (ISBN 90- edition ofsome ofthe seroUsby Eisenman and Wise(1992),wherein 04-100482), LCCN 94-017429. restorations appear far toofrequently and carry too much interpre- tive import. -

The Making of the Encyclopaedia Judaica and the Jewish Encyclopedia

THE MAKING OF THE ENCYCLOPAEDIA JUDAICA AND THE JEWISH ENCYCLOPEDIA David B. Levy, Ph. D., M.L.S. Description: The Jewish Encyclopedia and Encyclopaedia Judaica form a key place in most collections of Judaica. Both works state that they were brought into being to combat anti-Semitism. This presentation treats the reception history of both the JE and EJ by looking at the comments of their admirers and critics. It also assesses how both encyclopedias mark the application of social sciences and emphasis on Jewish history, as well as anthropology, archeology, and statistics. We will consider the differences between the JE and EJ, some of the controversies surrounding the making of the encyclopedias, and the particular political, ideological, and cultural perspectives of their contributing scholars. Introduction: David B. Levy (M.A., ’92; M.L.S., ’94; Ph. D., 2002) received a Ph. D. in Jewish studies with concentrations in Jewish philosophy, biblical The 1901-1906 Jewish Encyclopedia and archeology, and rabbinics on May 23, 2002, from the 1972 Encyclopaedia Judaica form an Baltimore Hebrew University. David has worked in important place in collections of Judaica. the Humanities Department of the Enoch Pratt Public Library since 1994. He authored the Enoch Both works were brought into being to Pratt Library Humanities annotated subject guide combat anti-Semitism, to enlighten the web pages in philosophy (24 categories), ancient and public of new discoveries, and to modern languages (Hebrew, Greek, Latin, French, Spanish, German), and religion. He is widely disseminate Jewish scholarship. Both published. encyclopedias seek to counter-act the lack of knowledge of their generations and wide spread assimilation. -

Genizah Fragments

To receive Genizah What’s in your suitcase? Fragments, to inquire What do rice, locks, rat traps, a potentially hazardous voyage about the Collection, coconut scraper, several ladles across the Indian Ocean. or to learn how to assist and four bed legs have in Elizabeth Lambourn’s with its preservation common? The foundations of a Abraham’s Luggage: a social life and study, please write Two Ronnies’ sketch? Maybe, of things in the Medieval Indian to Dr Ben Outhwaite, but they are all items that Ocean world mines this text, Head of the Genizah Abraham ben Yijū, the twelfth- and its wider context, as a study HOW YOU CAN HELP YOU HOW Research Unit, at century Jewish trader, packed in material culture. The book is Cambridge University for a journey back across the actually quite remarkable in the The Newsletter of the Taylor-Schechter Genizah Research Unit, Cambridge University Library No. 77 April 2019 Library, West Road, sea from his adopted home of detail it manages to extract Cambridge, CB3 9DR, Mangalore. Abraham, who was from a single Genizah the subject of Amitav Ghosh’s document, one that actually England. celebrated In an Antique Land, came to Elizabeth’s attention More fragments of early Torah scroll come to light made two lengthy sojourns on when she reviewed Mordechai takes on a life in the wider The Library can be the Malabar Coast, before Friedman and S. D. Goitein’s world of scholarship, reached by fax (01223) sailing back across the Indian India Traders for the journal informing areas of inquiry that 333160 or by telephone In 1959 the paleographer Ocean to Yemen for the last South Asian Studies. -

Intertextuality of Translations Into and From

Cultural and Religious Studies, September 2019, Vol. 7, No. 9, 477-482 doi: 10.17265/2328-2177/2019.09.002 D DAVID PUBLISHING Intertextuality of Translations Into and From Judaeo-Arabic as a Transformative Platform in Jewish-Arabic Universalism: The Case of Legal Monographs of the Late Geonim Neri Y. Ariel The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Israel In medieval times, translators of Judaeo-Arabic literature living in Islamic lands were fluent in Arabic as this was the lingua franca and, in many cases, their mother tongue. This is only rarely the case for the contemporary scholar. This creates enormous challenges for the modern translators of their works. However, this challenge is an opportunity to bridge cultural and historical gaps by increased accuracy the hallmark of modern scholarship. This interdisciplinary discourse establishes the co-religious Dasein. The research tools which demand knowledge not only of Jewish sources but rather of Islamic texts allow for greater appreciation of contacting influences. Rav Y. al-Barceloni of the 12th century, among others, translated into Hebrew several works of the Geonim with his own halakhic interpretations, interpolations, and expansions. When scholars come today to comprehend anew, these compilations they paradoxically are more reflective of the original text than scholars of the middle ages who were contemporaneous with these texts. Nonetheless insofar as the translations are into Hebrew, they produce insular affect on the cultural product, leaving it within the Jewish fold. This fact forces scholars who desire to communicate with the broader audience to publish their results in European languages. In mediaeval studies, this is not as often as one thinks. -

The Tiberian Tradition in Common Bibles from the Cairo Genizah

Cambridge Semitic Languages and Cultures Hornkohl and Khan (eds.) Studies in Semitic Vocalisation and Studies in Semitic Vocalisation Reading Traditions and Reading Traditions Aaron D. Hornkohl and Geoffrey Khan (eds.) EDITED BY AARON D. HORNKOHL AND GEOFFREY KHAN This volume brings together papers rela� ng to the pronuncia� on of Semi� c languages and the representa� on of their pronuncia� on in wri� en form. The papers focus on sources representa� ve of a period that stretches from late an� quity un� l the Middle Ages. A large propor� on of them concern reading tradi� ons of Biblical Hebrew, especially the vocalisa� on nota� on systems used to represent them. Also discussed are orthography and the wri� en representa� on of prosody. Beyond Biblical Hebrew, there are studies concerning Punic, Biblical Aramaic, Syriac, and Arabic, as well as post-biblical tradi� ons of Hebrew such as piyyuṭ and medieval Hebrew poetry. There were many parallels and interac� ons between these various language Studies in Semitic Vocalisation tradi� ons and the volume demonstrates that important insights can be gained from such a wide range of perspec� ves across diff erent historical periods. As with all Open Book publica� ons, this en� re book is available to read for free on the publisher’s website. Printed and digital edi� ons, together with supplementary digital material, can also be found here: www.openbookpublishers.com Cover image: Detail from a bilingual La� n-Punic inscrip� on at the theatre at Lepcis Magna, IRT 321 (accessed from h� ps://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Inscrip� on_Theatre_Lep� s_Magna_Libya.JPG). -

With Letters of Light: Studies in the Dead Sea Scrolls, Early Jewish

With Letters of Light rwa lç twytwab Ekstasis Religious Experience from Antiquity to the Middle Ages General Editor John R. Levison Editorial Board David Aune · Jan Bremmer · John Collins · Dyan Elliott Amy Hollywood · Sarah Iles Johnston · Gabor Klaniczay Paulo Nogueira · Christopher Rowland · Elliot R. Wolfson Volume 2 De Gruyter With Letters of Light rwa lç twytwab Studies in the Dead Sea Scrolls, Early Jewish Apocalypticism, Magic, and Mysticism in Honor of Rachel Elior rwayla ljr Edited by Daphna V. Arbel and Andrei A. Orlov De Gruyter ISBN 978-3-11-022201-2 e-ISBN 978-3-11-022202-9 ISSN 1865-8792 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data With letters of light : studies in the Dead Sea scrolls, early Jewish apocalypti- cism, magic and mysticism / Andrei A. Orlov, Daphna V. Arbel. p. cm. - (Ekstasis, religious experience from antiquity to the Middle Ages;v.2) Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: “This volume offers valuable insights into a wide range of scho- larly achievements in the study of the Dead Sea Scrolls, Jewish apocalypti- cism, magic, and mysticism from the Second Temple period to the later rabbinic and Hekhalot developments. The majority of articles included in the volume deal with Jewish and Christian apocalyptic and mystical texts constituting the core of experiential dimension of these religious traditions” - ECIP summary. ISBN 978-3-11-022201-2 (hardcover 23 x 15,5 : alk. paper) 1. Dead Sea scrolls. 2. Apocalyptic literature - History and criticism. 3. Jewish magic. 4. Mysticism - Judaism. 5. Messianism. 6. Bible. O.T. - Criticism, interpretation, etc. 7. Rabbinical literature - History and criticism. -

When Curator and Conservator Meet

krishnaveniv 22/11/08 14:23 CJSA_A_350143 (XML) Journal of the Society of Archivists Vol. 29, No. 1, April 2008, 41–56 When Curator and Conservator Meet: Some Issues Arising from the Preservation and Conservation of the Jacques Mosseri Genizah Collection at Cambridge University Library1 Rebecca Jefferson & Ngaio Vince-Dewerse Unearthed in Cairo in the early 20th century, the 7,000 fragments that constitute the Jacques Mosseri Genizah Collection are currently being conserved, digitised and catalogued at Cambridge University Library. This joint article, written by a curator and a conservator working on the Collection, provides a brief history of the manuscripts and an outline of the project. The difficulties created by pressures of time, funding, and provision of access are presented from both perspectives, followed by a more in-depth focus on the challenges posed by the treatment and housing of book structures in the collection. This unique approach serves to highlight potential tensions between conservation and curatorial concerns and the importance of working together to create satisfactory and ethical solutions. Introduction Jewish custom dictates that defective copies of the Bible must be stored and later buried.2 This process ensures that the written name of God is not destroyed but is allowed to degrade naturally. The place of storage (whether in a special chamber or underground) is known as a ‘genizah’.3 The synagogues of Old Cairo all had ‘genizot’ (plural), but, for reasons unknown, the Genizah in the Ben Ezra synagogue contained all manner of written material which was mostly left unburied and allowed to accumulate for over a thousand years.4 Correspondence to: Rebecca Jefferson (Curator), Ngaio Vince-Dewerse (Conservator), Cambridge University Library, Cambridge, UK. -

6. the Distinction Between Branches of Rabbinic Hebrew in Light of the Hebrew of the Late Midrash

Cambridge Semitic Languages and Cultures Heijmans Studies in Rabbinic Hebrew Studies in Rabbinic Hebrew Shai Heijmans (ed.) EDITED BY SHAI HEIJMANS This volume presents a collec� on of ar� cles centring on the language of the Mishnah and the Talmud — the most important Jewish texts (a� er the Bible), which were compiled in Pales� ne and Babylonia in the la� er centuries of Late An� quity. Despite the fact that Rabbinic Hebrew has been the subject of growing academic interest across the past Studies in Rabbinic Hebrew century, very li� le scholarship has been wri� en on it in English. Studies in Rabbinic Hebrew addresses this lacuna, with eight lucid but technically rigorous ar� cles wri� en in English by a range of experienced scholars, focusing on various aspects of Rabbinic Hebrew: its phonology, morphology, syntax, pragma� cs and lexicon. This volume is essen� al reading for students and scholars of Rabbinic studies alike, and appears in a new series, Studies in Semi� c Languages and Cultures, in collabora� on with the Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Cambridge. As with all Open Book publica� ons, this en� re book is available to read for free on the publisher’s website. Printed and digital edi� ons, together with supplementary digital material, can also be found here: www.openbookpublishers.com Cover image: A fragment from the Cairo Genizah, containing Mishnah Shabbat 9:7-11:2 with Babylonian vocalisati on (Cambridge University Library, T-S E1.47). Courtesy of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library. Cover design: Luca Baff a book 2 ebooke and OA edi� ons also available OPEN ACCESS OBP https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2020 Shai Heijmans. -

The Importance of the Geniza for Jewish History Author(S): Alexander Marx Source: Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research, Vol

The Importance of the Geniza for Jewish History Author(s): Alexander Marx Source: Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research, Vol. 16 (1946 - 1947), pp. 183-204 Published by: American Academy for Jewish Research Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3622270 Accessed: 26-07-2019 15:52 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms American Academy for Jewish Research is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research This content downloaded from 128.97.244.151 on Fri, 26 Jul 2019 15:52:50 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms THE IMPORTANCE OF THE GENIZA FOR JEWISH HISTORY ALEXANDER MARX Fifty years ago, in December 1896, Doctor Schechter went to Egypt and transferred the greater part of the treasures accumu- lated for more than a thousand years in the Cairo Geniza, some one hundred thousand fragments according to his estimate, to Cambridge, England. To mark the semicentennary of this epoch-making event in the history of Jewish scholarship, the American Academy for Jewish Research in December 1946 had arranged a symposium on THE IMPORTANCE OF THE GENIZA FOR JEWISH LEARNING of which the present paper was a part.