The Penn/Cambridge Genizah Fragment Project: Issues in Description, Access, and Reunification

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toolkit for Genizah Scholars: a Practical Guide for Neophytes

EAJS SUMMER LABORATORY FOR YOUNG GENIZAH RESEARCHERS Institut für den Nahen und Mittleren Osten, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, München, 6–7 September 2017 Toolkit for Genizah Scholars: A Practical Guide for Neophytes Compiled by Gregor Schwarb (SOAS, University of London) A) Introductory articles, general overviews, guides and basic reference works: Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2nd edition, vol. 16, cols. 1333–42 [http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/genizah- cairo]. Stefan REIF et al., “Cairo Geniza”, in The Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World, vol. 1, ed . N. Stillman, Leiden: Brill, 2010, pp. 534–555. Nehemya ALLONY, The Jewish Library in the Middle Ages: Book Lists from the Cairo Genizah, ed. Miriam FRENKEL and Haggai BEN-SHAMMAI with the participation of Moshe SOKOLOW, Jerusalem: Ben-Zvi Institute, 2006 [Hebrew]. An update of JLMA, which will include additional book lists and inventories from the Cairo Genizah, is currently being prepared. Haggai BEN-SHAMMAI, “Is “The Cairo Genizah” a Proper Name or a Generic Noun? On the Relationship between the Genizot of the Ben Ezra and the Dār Simḥa Synagogues”, in “From a Sacred Source”: Genizah Studies in Honour of Professor Stefan C. Reif, ed. Ben Outhwaite and Siam Bhayro, Leiden: Brill, 2011, pp. 43–52. Rabbi Mark GLICKMAN, Sacred Treasure: The Cairo Genizah. The Amazing Discoveries of Forgotten Jewish History in an Egyptian Synagogue Attic, Woodstock: Jewish Lights Publishing, 2011. Adina HOFFMAN and Peter COLE, Sacred Trash: The Lost and Found World of the Cairo Geniza, New York: Nextbook, Schocken, 2010. Simon HOPKINS, “The Discovery of the Cairo Geniza”, in Bibliophilia Africana IV (Cape Town 1981). -

1 Between Egypt and Yemen in the Cairo Genizah Amir Ashur Center

Between Egypt and Yemen in the Cairo Genizah Amir Ashur Center for the Study of Conversion and Inter-religious Encounters, Ben Gurion University, the Interdisciplinary Center for the Broader Application of Genizah Research, University of Haifa, and the Department of Hebrew Culture, Tel Aviv University [email protected] Ben Outhwaite University of Cambridge [email protected] Abstract A study of two documents from the Cairo Genizah, a vast repository of medieval Jewish writings recovered from a synagogue in Fusṭāṭ, Egypt, one hundred years ago, shows the importance of this archive for the history of medieval Yemen and, in particular, for the role that Yemen played in the Indian Ocean trade as both a commercial and administrative hub. The first document is a letter from Aden to Fusṭāṭ, dated 1133 CE, explaining the Aden Jewish community’s failure to raise funds to send to the heads of the Palestinian Gaonate in Egypt. It signals the decline of that venerable institution and the increasing independence of the Yemeni Jews. The second text is a legal document, produced by an Egyptian Jewish trader who intended to travel to Yemen, but who wished to ensure his wife was provided for in his absence. Both documents show the close ties between the Egyptian and Yemeni Jewish communities and the increasing commercial importance of Yemen to Egyptian traders. Keywords Cairo Genizah, history, India trade, al-Ǧuwwa, Hebrew, Judaeo- Arabic, marriage, Jewish leadership, legal contract, Aden, Fusṭāṭ. 1. Introduction The discovery of a vast store of manuscripts and early printed material in the Ben Ezra Synagogue in Fusṭāṭ at the end of the nineteenth century revolutionised the academic study of Judaism and provided a wealth of primary sources for the scrutiny of the Mediterranean world at large in the High Middle Ages and Early Modern period. -

1 I. Introduction: the Following Essay Is Offered to the Dear Reader to Help

I. Introduction: The power point presentation offers a number of specific examples from Jewish Law, Jewish history, Biblical Exegesis, etc. to illustrate research strategies, techniques, and methodologies. The student can better learn how to conduct research using: (1) online catalogs of Judaica, (2) Judaica databases (i.e. Bar Ilan Responsa, Otzar HaHokmah, RAMBI , etc.], (3) digitized archival historical collections of Judaica (i.e. Cairo Geniza, JNUL illuminated Ketuboth, JTSA Wedding poems, etc.), (4) ebooks (i.e. HebrewBooks.org) and eReference Encyclopedias (i.e., Encyclopedia Talmudit via Bar Ilan, EJ, and JE), (5) Judaica websites (e.g., WebShas), (5) and some key print sources. The following essay is offered to the dear reader to help better understand the great gains we make as librarians by entering the online digital age, however at the same time still keeping in mind what we dare not loose in risking to liquidate the importance of our print collections and the types of Jewish learning innately and traditionally associate with the print medium. The paradox of this positioning on the vestibule of the cyber digital information age/revolution is formulated by my allusion to continental philosophies characterization of “The Question Concerning Technology” (Die Frage ueber Teknologie) in the phrase from Holderlin‟s poem, Patmos, cited by Heidegger: Wo die Gefahr ist wachst das Retende Auch!, Where the danger is there is also the saving power. II. Going Digital and Throwing out the print books? Critique of Cushing Academy’s liquidating print sources in the library and going automated totally digital online: Cushing Academy, a New England prep school, is one of the first schools in the country to abandon its books. -

The Formation of the Talmud

Ari Bergmann The Formation of the Talmud Scholarship and Politics in Yitzhak Isaac Halevy’s Dorot Harishonim ISBN 978-3-11-070945-2 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-070983-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-070996-4 ISSN 2199-6962 DOI https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110709834 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number: 2020950085 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2021 Ari Bergmann, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston. The book is published open access at www.degruyter.com. Cover image: Portrait of Isaac HaLevy, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Isaac_halevi_portrait. png, „Isaac halevi portrait“, edited, https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ legalcode. Typesetting: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com Chapter 1 Y.I. Halevy: The Traditionalist in a Time of Change 1.1 Introduction Yitzhak Isaac Halevy’s life exemplifies the multifaceted experiences and challenges of eastern and central European Orthodoxy and traditionalism in the nineteenth century.1 Born into a prominent traditional rabbinic family, Halevy took up the family’s mantle to become a noted rabbinic scholar and author early in life. -

1 Attention All Lubavitchers of Chabad

ATTENTION ALL LUBAVITCHERS OF CHABAD AND JEWS EVERYWHERE!!!! The Rebbe is dead! The prophecy states that after seven generations when the Rebbe dies (he being the seventh) we would know who our Messiah is. For this reason I send you this OPEN EPISTLE!1 My Hebrew name is Nahum Khazinov and I am of Russian Jewish descent from both parents. My father is a Kohen and my mother is a Kohen which makes me of this same lineage of our high priests (Kohen ha-Gadowl) that goes all the way back to Aaron the brother of Moses from the tribe of Levi even as it is written: "For thus says the Lord: David shall never lack a man to sit on the throne of the house of Israel, and the Levitical priests shall never lack a man in my presence to offer burnt offerings, to burn cereal offerings, and to make sacrifices for ever" (Jeremiah 33:17-18). This, my letter to you, may it be in the sight and presence of my God and yours, in the presence of the Holiest Lord and in His Holy Name and His Most Ineffable Name of Names, Ha Shem, let this, my letter, be my sacrifice and my burnt offerings, may it be even like burnt cereal offerings for the sufferings of my people, who suffer not knowing where to look or which way to turn for our Messiah, whose Presence is about to be known throughout the entire world, from this time forth and forever more---the zeal of the Lord of Hosts shall do this. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Links in a chain: Early modern Yiddish historiography in the northern Netherlands (1743-1812) Wallet, B.T. Publication date 2012 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Wallet, B. T. (2012). Links in a chain: Early modern Yiddish historiography in the northern Netherlands (1743-1812). General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:29 Sep 2021 LINKS IN A CHAIN A IN LINKS UITNODIGING tot het bijwonen van de LINKS IN A CHAIN publieke verdediging van mijn proefschrift Early modern Yiddish historiography from the northern Netherlands, 1743-1812 LINKS IN A CHAIN Early modern Yiddish historiography from the northern the northern Yiddish historiography from Early modern Early modern Yiddish historiography in the northern Netherlands, 1743-1812 op vrijdag 2 maart 2012 om 11.00 uur in de Aula van de Universiteit van Amsterdam, Singel 411. -

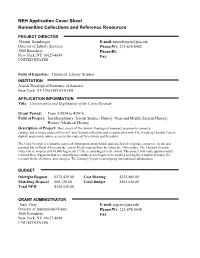

NEH Application Cover Sheet Humanities Collections and Reference Resources

NEH Application Cover Sheet Humanities Collections and Reference Resources PROJECT DIRECTOR Naomi Steinberger E-mail:[email protected] Director of Library Services Phone(W): 212-678-8982 3080 Broadway Phone(H): New York, NY 10027-4649 Fax: UNITED STATES Field of Expertise: Technical: Library Science INSTITUTION Jewish Theological Seminary of America New York, NY UNITED STATES APPLICATION INFORMATION Title: Conservation and Digitization of the Cairo Genizah Grant Period: From 5/2014 to 4/2016 Field of Project: Interdisciplinary: Jewish Studies; History: Near and Middle Eastern History; History: Medieval History Description of Project: The Library of The Jewish Theological Seminary proposes to conserve, catalog, and re-house material from its Cairo Genizah collection and, in partnership with The Friedberg Genizah Project, digitize and provide online access to this material for scholars and the public. The Cairo Genizah is a valuable source of information about Jewish and non-Jewish religious, economic, social, and personal life in North Africa and the eastern Mediterranean from the 9th to the 19th century. The Library's Genizah collection is comprised of 43,000 fragments ??? the second-largest in the world. This project will make approximately 6,000 of these fragments that are currently unreadable or too fragile to be handled and digitized widely available for research for the first time, and complete The Library???s part in an ongoing international collaboration. BUDGET Outright Request $272,429.00 Cost Sharing $222,469.00 Matching Request $68,120.00 Total Budget $563,018.00 Total NEH $340,549.00 GRANT ADMINISTRATOR Josie Gray E-mail:[email protected] Director of Institutional Grants Phone(W): 212-678-8048 3080 Broadway Fax: New York, NY 10027-4649 UNITED STATES The Library of The Jewish Theological Seminary Application to NEH Division of Preservation and Access, HCRR Program, July 2013 Implementation Grant for Conservation and Digitization of the Cairo Genizah 1. -

A Jewish Knight in Shining Armour: Messianic Narrative and Imagination in Ashkenazic Illuminated Manuscripts

A JEWISH KNIGHT IN SHINING ARMOUR: MESSIANIC NARRATIVE AND IMAGINATION IN ASHKENAZIC ILLUMINATED MANUSCRIPTS Sara Offenberg The artistic and textual evidence of thirteenth- and fourteenth-century Ashkenaz reveals an imagined reality from which we learn that some Jews imagined themselves as aristocrats and knights, despite the fact that the actuality of their everyday lives in medieval Ashkenaz was far from noble or chivalric.1 In recent years, the imagined identity of Jews portraying themselves as knights has received the attention of scholars, most recently Ivan G. Marcus, whose study focuses on the self-representation of Jews as knights, mainly in written sources.2 Marcus discusses the dissonance between actual Christian knights in the Middle Ages, whom he identifies with the crusaders, and the fact that Jews considered themselves knights. He explains that Jewish self-comparison to knights seems to have begun in the shared religious frenzy that started with Pope Urban II’s speech at Clermont on 27 November 1095, for an armed pilgrimage to Jerusalem, that later came to be called the First Crusade.3 This phenomenon, which began after the First Crusade, reached a climax during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries in Jewish written and artistic form. A number of Hebrew manuscripts contain scenes of knights. They portray characters of a noble and aristocratic nature, as shown in the research of Sarit Shalev-Eyni, who focused on the study of manuscripts made around the Lake Constance region in the fourteenth century.4 In this paper, I shall investigate the significance of warriors and knights illustrated in Hebrew manuscripts from thirteenth-century Ashkenaz with regard to the battle these warriors are symbolically fighting and the incongruity between art and reality, with a focus on Jewish imaginative ideas of the messiah. -

Martinez, Florentino Garcia. the Dead Sea Scrolls Translated: the Qumran Texts in English

Prof. Scott B. Noegel Chair, Dept. of Near Eastern Languages and Civilization University of Washington Book review: Martinez, Florentino Garcia. The Dead Sea Scrolls Translated: The Qumran Texts in English. Wilfred G. E. Watson, trans. Leiden: E.}. Brill, 1994. First Published in: Digest of Middle Eastern Studies 4/4 (1995), 78-85. ~ ) j"a{{1995 ~ ~ 'Roo(~aT/{{%anllscn'pts the more cumbersome scholarly sigla of the officinl publicntion. While the author admits that the lack of notes potentinlly could prevent the student from grasping "the literary, historical, and theological problems" (p. xxviii) which the scrolls present, the benefits ofthis volume to the interested reader will outweigh by far he Dead Sea Scrolls Translated: any drawbacks. Other English versions ofthe seroUspale in compar- The Qumran Texts in English ison (cf. the now out.of-date Gaster [1956] and the incomplete T Vermes [1995J,the latter ofwhich translates only 70 manuscripts). This book has many positive attributes. The line numbering Florentino Garcia Martinez informs the reader exactly where words appear in the texts. In addition, we may thank Martinez for keeping restorations to a Translated by Wilfred G. E. Watson minimum, despite the fragmentary nature of many of the scrolls. Excessive restoration of any ancient text almost always leads to a Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1994,lxvii, 513 pages. $80 cloth misunderstanding of that text. Compare, for example, the recent (ISBN 90-04-10088-1), $30 paperback (ISBN 90- edition ofsome ofthe seroUsby Eisenman and Wise(1992),wherein 04-100482), LCCN 94-017429. restorations appear far toofrequently and carry too much interpre- tive import. -

The Making of the Encyclopaedia Judaica and the Jewish Encyclopedia

THE MAKING OF THE ENCYCLOPAEDIA JUDAICA AND THE JEWISH ENCYCLOPEDIA David B. Levy, Ph. D., M.L.S. Description: The Jewish Encyclopedia and Encyclopaedia Judaica form a key place in most collections of Judaica. Both works state that they were brought into being to combat anti-Semitism. This presentation treats the reception history of both the JE and EJ by looking at the comments of their admirers and critics. It also assesses how both encyclopedias mark the application of social sciences and emphasis on Jewish history, as well as anthropology, archeology, and statistics. We will consider the differences between the JE and EJ, some of the controversies surrounding the making of the encyclopedias, and the particular political, ideological, and cultural perspectives of their contributing scholars. Introduction: David B. Levy (M.A., ’92; M.L.S., ’94; Ph. D., 2002) received a Ph. D. in Jewish studies with concentrations in Jewish philosophy, biblical The 1901-1906 Jewish Encyclopedia and archeology, and rabbinics on May 23, 2002, from the 1972 Encyclopaedia Judaica form an Baltimore Hebrew University. David has worked in important place in collections of Judaica. the Humanities Department of the Enoch Pratt Public Library since 1994. He authored the Enoch Both works were brought into being to Pratt Library Humanities annotated subject guide combat anti-Semitism, to enlighten the web pages in philosophy (24 categories), ancient and public of new discoveries, and to modern languages (Hebrew, Greek, Latin, French, Spanish, German), and religion. He is widely disseminate Jewish scholarship. Both published. encyclopedias seek to counter-act the lack of knowledge of their generations and wide spread assimilation. -

Nebuchadnezzar's Jewish Legions

Nebuchadnezzar’s Jewish Legions 21 Chapter 1 Nebuchadnezzar’s Jewish Legions: Sephardic Legends’ Journey from Biblical Polemic to Humanist History Adam G. Beaver Hebrew Antiquities There was no love lost between the Enlightened antiquarians Francisco Martínez Marina (1754–1833) and Juan Francisco de Masdeu (1744–1817).1 Though both were clerics – Martínez Marina was a canon of St Isidore in Madrid, and Masdeu a Jesuit – and voracious epigraphers, their lives and careers diverged in profound ways. Masdeu was an outsider in his profession: expelled from the Iberian Peninsula along with his fellow Jesuits in 1767, he spent most of the last fifty years of his life in Rome. There, substituting the descriptions and sketches forwarded by sympathetic amanuenses in Spain for the ancient remains he would never see firsthand, he continued to pursue his research in Iberian antiquities in open opposition to the state-sanctioned proj- ects conceived and carried out by the prestigious Real Academia de la Historia in Madrid. Martínez, in contrast, was the consummate insider, inhabiting the very centers of power denied to Masdeu: a member of the liberal parliament of 1820–23, he was also an early member, and eventually two-time president, of the Real Academia which Masdeu scorned. It was almost certainly as a staunch defender of the Real Academia’s massive research projects – especially its offi- cial catalogue of ancient Iberian inscriptions, which Masdeu proposed to better with his own inventory – that Martínez Marina acquired his palpable distaste for Masdeu, his methods, and his ideological commitments. 1 On Martínez Marina and Masdeu, see Roberto Mantelli, The Political, Religious and Historiographical Ideas of J.F. -

A Hebrew “Book Within Book” at Fisher Library, University of Sydney

Journal & Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales, vol. 152, part 2, 2019, pp. 160–187. ISSN 0035-9173/19/020160-28 A Hebrew “Book within Book” at Fisher Library, University of Sydney Gary A. Rendsburg Rutgers University Email: [email protected] Abstract This article presents the first Hebrew “book within book” to be found in Australia. Included within the binding of an early printed Hebrew book entitled Torat Moshe (Venice, 1601), housed at Rare Books and Special Collections, Fisher Library, University of Sydney, is a small parchment fragment containing only nineteen Hebrew letters (comprising four complete words and portions of three others). The article traces the path from discovery (first observed by Alan Crown in 1984) to identifi- cation (a medieval poem recited on the occasion of the circumcision ritual). The poem is known from only five other medieval manuscripts (London, Oxford, Erlangen, Jerusalem, New York), so that the small Sydney fragment is a crucial, albeit fragmentary, witness to a rarely attested and thus relatively unknown piece of medieval Jewish history and liturgy. Introduction older parchment fragment found within the uring the past several decades, research- book binding contains a text already known Ders in (mainly) European libraries to scholars, though naturally each witness have discovered the remnants of medieval thereto (even a fragmentary one) is precious manuscripts within the bindings and fly- in its own right. leaves of early printed books. The practice As with Latin and other European lan- of repurposing fragments of earlier manu- guages (English, French, German, Greek, scripts for the securing of bound books in etc.), so too with Hebrew.