Usable Pasts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moraimde315 Center Street (Rt

y A 24—MANCHESTER HERALD. Friday, April 13, 1990 LEGAL NOTICE DON’T KNOW Where to Is advertising expensive? TOWN OF BOLTON look next for a lob? How I cod CLEANING MISCELLANEOUS ■07 |j MISCELLANEOUS You'll be surprised now I CARS ZONING BOARD OF APPEALS about placing a “Situa 1SERVICES FOR SALE FOR SALE economical It Is to adver FOR SALE Notice is here by given that there will be a public hearing of the tion Wanted" ad In tise In Classified. 643-2711. classified? Zoning Board of >^peals, on Thursday, April 26, 1990 at 7 NO TIM E TO CLEAN. SAFES-New and used. DODGE - 1986. ’150’, 318 p.m. at the Bolton Town Hall, 222 Bolton Center Road, Bolton, Don't really like to END RO LLS Trade up or down. CIO, automatic, bed CT. A clean but hate to come f o o l ROOMMATES 27V4" width — 504 Liberal allowance for WANTED TO liner, tool box, 50K, 1. To hear appeal of Gary Jodoin, 23 Brian Drive for a rear home to a dirty house. I $5500. 742-8669. [ ^ W A N T E D 13" width — 2 for 504 clean safes In good Ibuy/ trade set-back variance for a porch. Coll us 1 We’re reaso condition. American 2. To hear appeal of MIton Hathaway, 40 Quarry Road for a nable and we do a good Newsprint and rolls can bs Graduating? House and picked up at the Manchester Security Corp. Of CT, WANTED: Antiques and special permit to excavate sand & gravel at 40 Quarry Road. -

G-Force 1500C Study Plans

The G‐Force 1500 Cruise Study Plans Design Profile G‐Force 1500C Design Overview G‐Force 1500C SPECIFICATIONS furls half the jib and winds in a reef or two in the main. Having the controls in the safety of the cockpit is ideal LOA 15.45 Metres especially if in the middle of the night offshore and of course BOA 7.90 Metres you need to have a good view of the sails from your winch station. DRAFT 0.550 Metres DISPLACEMENT 8000 Kilograms The decks are wide, clear and one level making walking around easy and safe, the trampolines fitted to the com- PAYLOAD 2600 Kilograms posite forebeam and all composite chainplates and stan- chions give very clean neat lines with no leaking fittings or BEAM TO LENGTH 14.5:1 bulky equipment on which to trip. MAST HEIGHT 19.30 Metres and grandchildren and it becomes clear our real require- ments are a little different now. Usher in the new G-Force FUEL CAPACITY 200 Litres 1500 “Cruise” design, this is definitely a better fit as she can WATER CAPACITY 500 Litres carry the extra cruising gear we need for that circumnaviga- tion, the toys we want and the comfortable accommodation HEADROOM 1900—1965 MM to have family and friends join us as and where they can. SAIL AREA (MAIN) 78 sqm CE compliance is optional with this design. European SAIL AREA (S/TACK JIB) 50 sqm owners and builders will require this. Displacement has been increased to carry the additional structural MOTORS 2 x 29-37hp Diesels requirements and provide good cruising payload. -

Chapter 10: the Alamo and Goliad

The Alamo and Goliad Why It Matters The Texans’ courageous defense of the Alamo cost Santa Anna high casualties and upset his plans. The Texas forces used the opportunity to enlist volunteers and gather supplies. The loss of friends and relatives at the Alamo and Goliad filled the Texans with determination. The Impact Today The site of the Alamo is now a shrine in honor of the defenders. People from all over the world visit the site to honor the memory of those who fought and died for the cause of Texan independence. The Alamo has become a symbol of courage in the face of overwhelming difficulties. 1836 ★ February 23, Santa Anna began siege of the Alamo ★ March 6, the Alamo fell ★ March 20, Fannin’s army surrendered to General Urrea ★ March 27, Texas troops executed at Goliad 1835 1836 1835 1836 • Halley’s Comet reappeared • Betsy Ross—at one time • Hans Christian Andersen published given credit by some first of 168 stories for making the first American flag—died 222 CHAPTER 10 The Alamo and Goliad Compare-Contrast Study Foldable Make this foldable to help you compare and contrast the Alamo and Goliad—two important turning points in Texas independence. Step 1 Fold a sheet of paper in half from side to side. Fold it so the left edge lays about 1 2 inch from the right edge. Step 2 Turn the paper and fold it into thirds. Step 3 Unfold and cut the top layer only along both folds. This will make three tabs. Step 4 Label as shown. -

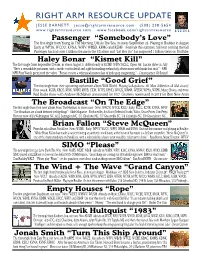

Right Arm Resource Update

RIGHT ARM RESOURCE UPDATE JESSE BARNETT [email protected] (508) 238-5654 www.rightarmresource.com www.facebook.com/rightarmresource 6/22/2016 Passenger “Somebody’s Love” The first single from Young As The Morning, Old As The Sea, in stores September 23 Playing in Boulder in August Early at WPYA, WCOO, KVNA, WFIV, WBSD, KFMG and KSMF Festivals this summer, full tour coming this fall Passenger has had over 1 billion streams in the US alone and “Let Her Go” has surpassed 1 billion views on YouTube Haley Bonar “Kismet Kill” The first single from Impossible Dream, in stores August 5 Added early at KCMP, WFIV, KCLC, Open Air Lucius dates in July “She’s a remarkable performer, with a terrific ear for detail and a gift for masking melancholy observations with hooks that stick.” - NPR NPR First Watch premiered the video “Bonar creates a whimsical masterclass of indie-pop songwriting.” - Consequence Of Sound Bastille “Good Grief” The first single from their upcoming sophomore album Wild World Playing Lollapalooza #1 Most Added on all AAA charts! First week: KGSR, KBCO, KINK, WXRV, KRVB, CIDR, WTTS, KPND, WNCS, WRNR, WZEW, WPYA, WXPK, Music Choice and more Red Rocks show with Andrew McMahon announced for 10/7 Grammy nominated in 2015 for Best New Artist The Broadcast “On The Edge” The first single from their new album From The Horizon, in stores now New: WNCW, WYCE, KSLU Early: KCLC, KDTR, KVNA, WFIV “The Broadcast are a band destined for big things” - Glide Magazine Produced by Jim Scott (Tedeschi Trucks, Wilco, Grace Potter, Tom Petty) On tour now: 6/23 Wilmington NC, 6/25 Lexington NC, 7/1 Charlotte NC, 7/7 Greenville SC, 7/8 Columbia SC, 7/9 Greensboro NC.. -

Nopa,Μ~E.: Sorqali:~

Complimentary b i Fall 1 A Election coverage interviews with Audrey Mclaughlin Sheila Copps . ~. All-p~rty coverage of; Employm·ent Debt_ ·Healthcare refgrf::p·olicy En vi roJ1m:e1tt NAFTA Violen.ee: ' Abori.ginal Self Gov$rn·ment Social Pr9gr~ms Childcare Culture Humart Rights Agric·ullure Fisheri>es Abortion New Rl~p:ro· Also in thls Technologies::· issue:· .lmmigt.J:ltign .·ME!nopa,µ~e.: Sorqali:~. ··>·victory for:. Rape•·,crtslt· ·c··•· •.·.··.··•k··.·c· w·· e!n·tres .. u·c Uu' page 2 Fa/11993 Editor: Joan Riggs Womenspeak Managing Editor: Caitlin McMorran-Frost Editing and production staff: Catherine Browning, Saira Fitzgerald, Valerie Mclennon, Michelle Simms, Lynne Tyler, Viviane Weitzner. Dear Woman/st leadership of the Conservative Who helped with this issue: Lucy Chapman, Lyse party to make a difference. Blanchard, Noelle-Domenique Willems, Michelle Lemay, Laura Kim Campbell's clinching of Defence minister Campbell's McFarlane, Joanne Steven, Donna Truesdale. Alex Keir, Jane From Inside Out the Tory crown is not a victory new policy of zero incidence Vock, and Anne, Leah, Daniel, & Matthew Haynes. by Patricia Ellen for women in Canada. I do not has not changed anything for Cresswell agree that Campbell's win will victims of harassment and Special thanks to the people who have financially give women more courage to discrimination who have assisted us with this issue: Roberta Hill, Lil & Tim Tyler, have high expectations. grievances with the Canadian Campbell's win will not help Barbara Chapman, Lucy Chapman, Claire Fellows, Lucy Dear Womanist: Armed Forces. Fellows, Ted Riggs. women and girls to realize they I joined the (RCAF) Canadian can be winners too, in any field. -

N.I.Il`Minskii and the Christianization of the Chuvash

Durham E-Theses Narodnost` and Obshchechelovechnost` in 19th century Russian missionary work: N.I.Il`minskii and the Christianization of the Chuvash KOLOSOVA, ALISON,RUTH How to cite: KOLOSOVA, ALISON,RUTH (2016) Narodnost` and Obshchechelovechnost` in 19th century Russian missionary work: N.I.Il`minskii and the Christianization of the Chuvash, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/11403/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 1 Narodnost` and Obshchechelovechnost` in 19th century Russian missionary work: N.I.Il`minskii and the Christianization of the Chuvash PhD Thesis submitted by Alison Ruth Kolosova Material Abstract Nikolai Il`minskii, a specialist in Arabic and the Turkic languages which he taught at the Kazan Theological Academy and Kazan University from the 1840s to 1860s, became in 1872 the Director of the Kazan Teachers‟ Seminary where the first teachers were trained for native- language schools among the Turkic and Finnic peoples of the Volga-Urals and Siberia. -

The Power of Heritage to the People

How history Make the ARTS your BUSINESS becomes heritage Milestones in the national heritage programme The power of heritage to the people New poetry by Keorapetse Kgositsile, Interview with Sonwabile Mancotywa Barbara Schreiner and Frank Meintjies The Work of Art in a Changing Light: focus on Pitika Ntuli Exclusive book excerpt from Robert Sobukwe, in a class of his own ARTivist Magazine by Thami ka Plaatjie Issue 1 Vol. 1 2013 ISSN 2307-6577 01 heritage edition 9 772307 657003 Vusithemba Ndima He lectured at UNISA and joined DACST in 1997. He soon rose to Chief Director of Heritage. He was appointed DDG of Heritage and Archives in 2013 at DAC (Department of editorial Arts and Culture). Adv. Sonwabile Mancotywa He studied Law at the University of Transkei elcome to the Artivist. An artivist according to and was a student activist, became the Wikipedia is a portmanteau word combining youngest MEC in Arts and Culture. He was “art” and “activist”. appointed the first CEO of the National W Heritage Council. In It’s Bigger Than Hip Hop by M.K. Asante. Jr Asante writes that the artivist “merges commitment to freedom and Thami Ka Plaatjie justice with the pen, the lens, the brush, the voice, the body He is a political activist and leader, an and the imagination. The artivist knows that to make an academic, a historian and a writer. He is a observation is to have an obligation.” former history lecturer and registrar at Vista University. He was deputy chairperson of the SABC Board. He heads the Pan African In the South African context this also means that we cannot Foundation. -

Easter As an Ecumenical Conundrum

Easter as an Ecumenical Conundrum Michael Straus* Questo sicuro e gaudïoso regno frequente in gente antica e in novella, viso e amore avea tutto ad un segno. O trina luce che ‘n unica stella scintillando a lor vista, sì li appaga! 1 guarda qua giuso a la nostra procella! This article examines the Easter festival from an ecumenical point of view, focusing on the Patristic period and the so-called “Easter Controversies” in the Early Church concerning the date on which the Resurrection should be observed, as a means of assessing both the validity of the resolution of such controversies and the possibly continuing impact of that resolution on the Church today. I will divide this examination into four parts. First, I will consider what guidance we have from the Scriptures as to how, if at all, the Church is to celebrate the Resurrection. Second, I will focus on the Easter Controversies, and in particular the quartodeciman position, in the context of the Council of Nicaea and Nicaea’s resulting decision concerning the need for a uniform date on which to celebrate Easter. Third, I will note the disputes that remained within the Church concerning the observance of Easter after Nicaea, notwithstanding the attempt at reaching full unity on this issue. Finally, I will attempt to gauge whether any failure to reach unity on the question of when to observe the Resurrection has any continuing impact on the Church today. I. The Easter Festival from a New Testament Point of View This is not the place for an extended treatment of worship practices in the New Testament, let alone for how such practices might be informed by Old Testament practices. -

Designing Sails Since 1969

SAILRITE SAIL KITS Designing sails since 1969. Catalina 30 Tall Rig Mainsail Kit by Frederick Leroy Carter F 31R Screecher Kit by Patrick Pettengill Capri 18 Main & Jib Sail Kits by Brent Stiles “ We built this sail ourselves!” Custom Lateen Main Kit by Steve Daigle -Karen Larson Building your own sail is a very rewarding and satisfying Each kit comes with the sail design data and a set of instructions experience. Not only is there a real sense of accomplishment, and illustrations that have been perfected from over 40 years of but the skills developed in the process will make you a more self- experience and feedback. Sail panels are pre-cut, labeled and reliant sailor. Sailrite makes the process very easy and affordable numbered for easy assembly. Panel overlap and hemming lines from start to finish by providing sail kits that include materials come plotted on each panel and double-sided tape is included used by professional sailmakers at up to 50% less the cost! to adhere panels together prior to sewing to ensure that draft and shape are maintained during construction. Batten pockets, Sailrite uses state-of-the-art design programs and hardware to windows, draft stripes, reef points, and other details will also prepare each kit. Sail panels and corner reinforcements are all come plotted on the appropriate panels if required for your sail. computer-cut and seaming lines are drawn along the edges. Draft, twist, and entry and exit curves are all carefully calculated, controlled, and positioned for each sail to maximize performance. Getting Started All materials are carefully selected by our sail designers to Getting started is easy and Sailrite’s expert staff is available toll best suit your application and only high quality sailcloths and free every working day to answer questions and help guide you laminates from Bainbridge, Challenge, Contender and others who through the ordering and construction process. -

April 2021 SW

Through the Study Window Peru Community Church 12 Elm Street Peru, NY 12972 April 2021 Page 1 From the Pastor’s Pen Rev. Peggi Eller “Rejoice and Be Glad! Yours is the Kingdom of God!” The Easter Story never changes in its most basic outline: Jesus died. The women came to the tomb. The tomb was empty. There was much rejoicing. The details of the story are highly dependent on us. Where do we focus our Upcoming Worship minds? In the past year, over a half-million new tombs were opened and Opportunities sealed in the US because of the COVID-19 pandemic. We have all experienced - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - too much death, isolation, fear, and loneliness. How can we rejoice? We 4/1 - Holy Thursday could choose to stand still in the grief because this has certainly been a grief- Zoom Worship at 6pm filled year. But the tomb where Jesus was laid was empty. At first Mary Celebrate the weeps that Jesus is gone, but then she sees that there is reason to rejoice. Last Supper Jesus invites them to go forward, leading his disciples to the next chapter of - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - the story. 4/2 - Good Friday 6pm Service of Easter is a time to rejoice. It is the time to rejoice about the stories of Shadows & Darkness in resurrection that have occurred all around us: the emergence of new life the Sanctuary & Zoom coming from the ground, the changes in patterns of life, the gift of time, the Masks & social interruption of busy calendars and the joy of newness. The Easter narrative never changes in its basic outline, but the stories, the memories, the distancing in effect happenings and the lessons-learned provide the specific details of the - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - reasons to rejoice for each of us each year. -

The Falcon, Volume 89, Issue 1 Sep. 27, 2106

theFalcon Volume 89, Issue 1 Quincy University Tuesday, September 27, 2016 CAMPUS PARKING QU’s David Jacob is in the minor leagues; read more about his success Beware the signs; park with caution DOMINIC MILES STAFF WRITER Students have been faced with a de- - page 12 cline of parking around Quincy Univer- sity’s campus. These no parking zones are on Chestnut, between the streets of 18th Soccer team travels to and 20th and Lind, between 20th and Germany; may be only 22nd street. trip many will take The “No QU Student Parking” signs went up in the middle of last school year, with the hope that students would abide by these signs. Both QU Security and the Quincy Police Department now enforce these signs and charge students $15 for being parked in a spot. Cars are parked along Chestnut Street between 18th and 20th Streets. Quincy aldermen complained on behalf of residents, as the school year Michael Nielson said. “It didn’t cross my unpaid parking tickets. If this continues started with too many students parking in mind that I could get a ticket from park- to happen, security will have to take even front of houses. ing alongside the curb just like everyone more measures than simply giving out “We’ve been working with our al- e l s e .” tickets. dermen to find a balance between being Nielson received a ticket for parking “Any car that continues to park in the - page 10 good neighbors and our own parking parallel on Lind facing east between 20th no parking zones without a QU sticker is needs,” Sam Lathrop, head of QU security, and 22nd. -

Journals 2015.Pdf

『国際言語文化』創刊号巻頭言 京都外国語大学国際言語文化学会 会長 京都外国語大学・京都外国語短期大学 学長 松田 武 2013 年早春,学校法人京都外国語大学における研究活動の中核をなす組織として,「京 都外国語大学国際言語文化学会」が設立されました。会員の皆様,関係の皆様には学会設 立に際しましてさまざまな方面からご支援・ご協力賜りましたことにあらためて厚くお礼 申し上げます。 設立から約二年が経過しましたが,この学会の設立はたいへん意義深いものだったと実 感しております。広く学術・教育・社会の発展に貢献するのはもちろんのことですが,未 来社会を担う大学院生をはじめとした若手研究者の育成もさまざまな活動を通して活発に なってまいりました。また,京都外国語大学内の各種研究会を本学会の研究活動の中に組 み入れることで,刺激し合い,触発し合うといった一層の相乗効果も生まれています。研 究活動は基本的には孤独であり,常に自分との闘いではありますが,学会活動を通して新 しい出会いや発見が生まれ,異分野に触れることによって互いの多様性を認め合い,さら に研究の幅が広がるものと期待しています。 本誌は,この学会の会員,京都外国語大学・京都外国語短期大学に勤務するすべての教 職員,本学園の学生や本学を卒業したすべての若手研究者が研鑽し,研究成果を公表する 機会を提供することを目的としています。本誌の刊行をもって会員の研究活動を共有でき, 会員の研究成果の一部を今後のさらなる発展につなげられることを大変嬉しく思います。 最後になりましたが,本学会,および,本誌には「国際言語文化」が含まれています。 これは,京都外国語大学の建学の精神が「言語を通して世界の平和を」であることと関連 があります。この建学の精神を実現すべく,グローバルな視点からみた言語と文化に関す る優れた論考が本誌から多数発信され,各研究・教育分野での学術的な議論を誘発するき っかけとなればと願っております。 国際言語文化 創刊号 目次 研究論文 アラモ砦事件再考・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・牛島 万 ・・・1 カンタン・メイヤスーの思弁的唯物論・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・影浦 亮平 ・・・19 クリステーロの乱の展開と軍事社会史における士気の問題・・・・・・・古畑 正富 ・・・31 ブラジルにおける民主主義と政治指導者のカリスマ性・・・・・・・・・住田 育法 ・・・43 研究ノート 視覚障害をもつ留学生受け入れの課題 -京都外国語大学における授業外支援の取り組み-・・・・・・・・・・北川 幸子 ・・・57 辻野 美穂子 古澤 純 ラボラトリー方式の体験学習を取り入れた日本語クラスの試み・・・・・・・小松 麻美・・・67 第二言語習得の認知プロセスからみた協働学習の効果 -平和を題材にした日本語授業での協働学習の実践―・・・・・・・・中西 久実子 ・・・81 国際言語文化創刊号(2015 年 3 月) International Language and Culture First issue アラモ砦事件再考 牛島万 Contents Articles A Critical Study of the Fall of the Alamo・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・Takashi USHIJIMA 要旨 En este artículo, se trata del período desde la inmigración de los anglosajones a Texas hasta la Speculative materialism of Quentin Meillassoux・・・・・・・・・・・・・Ryohei