VOLUME 2, 2006 Dream and Reality: Turn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

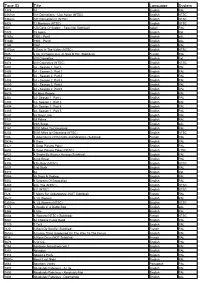

Tape ID Title Language Type System

Tape ID Title Language Type System 1361 10 English 4 PAL 1089D 10 Things I Hate About You (DVD) English 10 DVD 7326D 100 Women (DVD) English 9 DVD KD019 101 Dalmatians (Walt Disney) English 3 PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English 6 NTSC KD040 101 Dalmations (Live) English 3 PAL KD041 102 Dalmatians English 3 PAL 0665 12 Angry Men English 4 PAL 0044D 12 Angry Men (DVD) English 10 DVD 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English 3 NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian 4 PAL 6016 13 Conversations About One Thing (NTSC) English 1 NTSC 0189DN 13 Going On 30 (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 7080D 13 Going On 30 (DVD) English 9 DVD 0179DN 13 Moons (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 3050D 13th Warrior (DVD) English 10 DVD 6291 13th Warrior (NTSC) English 3 nTSC 5172D 1492 - Conquest Of Paradise (DVD) English 10 DVD 3165D 15 Minutes (DVD) English 10 DVD 6568 15 Minutes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 7122D 16 Years Of Alcohol (DVD) English 9 DVD 1078 18 Again English 4 Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English 4 pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English 4 pAL 1244 1941 English 4 PAL 0072DN 1Love (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0141DN 2 Days (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 3256D 2 Fast 2 Furious (DVD) English 10 DVD 5276D 2 Gs And A Key (DVD) English 4 DVD f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French 4 PAL X059D 20 30 40 (DVD) English 9 DVD 1304 200 Cigarettes English 4 Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 3172D 2001 - A Space Odyssey (DVD) English 10 DVD 3032D 2010 - The Year -

Westminsterresearch the Artist Biopic

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch The artist biopic: a historical analysis of narrative cinema, 1934- 2010 Bovey, D. This is an electronic version of a PhD thesis awarded by the University of Westminster. © Mr David Bovey, 2015. The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: ((http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] 1 THE ARTIST BIOPIC: A HISTORICAL ANALYSIS OF NARRATIVE CINEMA, 1934-2010 DAVID ALLAN BOVEY A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Westminster for the degree of Master of Philosophy December 2015 2 ABSTRACT The thesis provides an historical overview of the artist biopic that has emerged as a distinct sub-genre of the biopic as a whole, totalling some ninety films from Europe and America alone since the first talking artist biopic in 1934. Their making usually reflects a determination on the part of the director or star to see the artist as an alter-ego. Many of them were adaptations of successful literary works, which tempted financial backers by having a ready-made audience based on a pre-established reputation. The sub-genre’s development is explored via the grouping of films with associated themes and the use of case studies. -

Full Text (PDF)

Document generated on 09/28/2021 2:53 a.m. Séquences La revue de cinéma Vues d’ensemble Le cinéma québécois des années 90 Number 215, September–October 2001 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/48679ac See table of contents Publisher(s) La revue Séquences Inc. ISSN 0037-2412 (print) 1923-5100 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this note (2001). Vues d’ensemble. Séquences, (215), 51–60. Tous droits réservés © La revue Séquences Inc., 2000 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ À LA VERTICALE DE L'ÉTÉ D'une rare beauté, À la verticale de l'été, objet insolite s'il en est un dans le paysage cinématographique estival, marque le retour tant attendu de Trân Anh Hùng après Cyclo/Xich lo (1995) et L'Odeur de la papaye verte/Mui du du xanh (1993). Véritable esthète du cinéma, le réalisateur français d'origine vietnamienne confirme, avec ce troisième long métrage, son éton nant sens du cadre et du rythme. S'appuyant sur une trame narrative d'une grande simplicité (certes tantôt peu convaincante, tantôt trop elliptique), Trân Anh Hùng renoue avec le délicat lyrisme de sa première œuvre pour capter la douce A la verticale de l'été immobilité propre aux siestes de son gnifiques où le jaune des murs, le vert de la enfance et communiquer au spectateur la nature luxuriante, le bleu de l'eau, le blanc lancinante sensualité dont est empreint de la peau des femmes se répondent, sem l'été vietnamien. -

Camera Lucida Symphony, Among Others

Pianist REIKO UCHIDA enjoys an active career as a soloist and chamber musician. She performs Taiwanese-American violist CHE-YEN CHEN is the newly appointed Professor of Viola at regularly throughout the United States, Asia, and Europe, in venues including Suntory Hall, the University of California, Los Angeles Herb Alpert School of Music. He is a founding Avery Fisher Hall, Alice Tully Hall, the 92nd Street Y, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, member of the Formosa Quartet, recipient of the First-Prize and Amadeus Prize winner the Kennedy Center, and the White House. First prize winner of the Joanna Hodges Piano of the 10th London International String Quartet Competition. Since winning First-Prize Competition and Zinetti International Competition, she has appeared as a soloist with the in the 2003 Primrose Competition and “President Prize” in the Lionel Tertis Competition, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Santa Fe Symphony, Greenwich Symphony, and the Princeton Chen has been described by San Diego Union Tribune as an artist whose “most impressive camera lucida Symphony, among others. She made her New York solo debut in 2001 at Weill Hall under the aspect of his playing was his ability to find not just the subtle emotion, but the humanity Sam B. Ersan, Founding Sponsor auspices of the Abby Whiteside Foundation. As a chamber musician she has performed at the hidden in the music.” Having served as the principal violist of the San Diego Symphony for Chamber Music Concerts at UC San Diego Marlboro, Santa Fe, Tanglewood, and Spoleto Music Festivals; as guest artist with Camera eight seasons, he is the principal violist of the Mainly Mozart Festival Orchestra, and has Lucida, American Chamber Players, and the Borromeo, Talich, Daedalus, St. -

Tracing Noise: Writing In-Between Sound by Mitch Renaud Bachelor

Tracing Noise: Writing In-Between Sound by Mitch Renaud Bachelor of Music, University of Toronto, 2012 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies in the Department of French, the School of Music, and Cultural, Social, and Political Thought Mitch Renaud, 2015 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Tracing Noise: Writing In-Between Sound by Mitch Renaud Bachelor of Music, University of Toronto, 2012 Supervisory Committee Emile Fromet de Rosnay, Department of French and CSPT Supervisor Christopher Butterfield, School of Music Co-Supervisor Stephen Ross, Department of English and CSPT Outside Member iii Abstract Supervisory Committee Emile Fromet de Rosnay (Department of French and CSPT) Supervisor Christopher Butterfield (School of Music) Co-Supervisor Stephen Ross (Department of English and CSPT) Outside Member Noise is noisy. Its multiple definitions cover one another in such a way as to generate what they seek to describe. My thesis tracks the ways in which noise can be understood historically and theoretically. I begin with the Skandalkonzert that took place in Vienna in 1913. I then extend this historical example into a theoretical reading of the noise of Derrida’s Of Grammatology, arguing that sound and noise are the unheard of his text, and that Derrida’s thought allows us to hear sound studies differently. Writing on sound must listen to the noise of the motion of différance, acknowledge the failings, fading, and flailings of sonic discourse, and so keep in play the aporias that constitute the field of sound itself. -

Syllabus for a Given Week

Interdepartmental Graduate Seminar 653 Spring 2012 Christiane Hertel Department of History of Art E-mail: [email protected] Imke Meyer Department of German E-mail: [email protected] GSEM 653: Fractured Foundations: Empire’s Ends and Modernism’s Beginnings. The Case of Vienna 1900. Viennese Modernism emerged against the backdrop of a multi-ethnic and multi-national empire that was increasingly imperiled both by internal strife and by external political and military pressures. The fractured state of the Habsburg Empire is mirrored in the forms and contents of the culture of Vienna around 1900. While the strength and cohesion of the empire were diminishing, ever richer visual, literary, philosophical, and scientific cultures were developing. Art, architecture, theater, literature, philosophy, and psychoanalysis were grappling with the seismic shifts which constructions of gender, family, class, ethnic identity, and religious identity were undergoing as the Habsburg Empire began to crumble. The critical discussions of visual culture, literary works, and psychoanalytic texts (by artists and writers such as Freud, Hofmannsthal, Hoffmann, Klimt, Kokoschka, Loos, Musil, Schiele, Schnitzler, and Weininger) in this interdisciplinary seminar will be framed by theoretical readings on the history and concept of empire. Available for purchase at the Bryn Mawr College Bookshop: Peter Altenberg, Ashantee. Steven Beller, A Concise History of Austria. Hugo von Hofmannsthal, The Lord Chandos Letter. Robert Musil, The Confusions of Young Törless. Arthur Schnitzler, Lieutenant Gustl. Carl Schorske, Fin-de-siècle Vienna: Politics and Culture. All other readings will be made available on Blackboard, in photocopied form, or on our course reserve in Carpenter Library. An ARTstor folder for our seminar contains image groups for most seminar meetings (1/19, 2/16, 2/23, 3/1, 3/15, 4/5, 4/12). -

Zalman Shneour and Leonid Andreyev, David Vogel and Peter Altenberg Lilah Nethanel Bar-Ilan University

Hidden Contiguities: Zalman Shneour and Leonid Andreyev, David Vogel and Peter Altenberg Lilah Nethanel Bar-Ilan University abstract: The map of modern Jewish literature is made up of contiguous cultural environments. Rather than a map of territories, it is a map of stylistic and conceptual intersections. But these intersections often leave no trace in a translation, a quotation, a documented encounter, or an archived correspondence. We need to reconsider the mapping of modern Jewish literature: no longer as a defined surface divided into ter- ritories of literary activity and publishing but as a dynamic and often implicit set of contiguities. Unlike comparative research that looks for the essence of literary influ- ence in the exposure of a stylistic or thematic similarity between works, this article discusses two cases of “hidden contiguities” between modern Jewish literature and European literature. They occur in two distinct contact zones in which two European Jewish authors were at work: Zalman Shneour (Shklov, Belarus, 1887–New York, 1959), whose early work, on which this article focuses, was done in Tsarist Russia; and David Vogel (Podolia, Russia, 1891–Auschwitz, 1944), whose main work was done in Vienna after the First World War. rior to modern jewish nationalism becoming a pragmatic political organization, modern Jewish literature arose as an essentially nonsovereign literature. It embraced multinational contexts and was written in several languages. This literature developed Pin late nineteenth-century Europe on a dual basis: it expressed the immanent national founda- tions of a Jewish-national renaissance, as well as being deeply inspired by the host environment. It presents a fascinating case study for recent research on transnational cultures, since it escapes any stable borderline and instead manifests conflictual tendencies of disintegration and reinte- gration, enclosure and permeability, outreach and localism.1 1 Emily S. -

Tape ID Title Language System

Tape ID Title Language System 1375 10 English PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English NTSC 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian PAL 1078 18 Again English Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English pAL 1244 1941 English PAL 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English NTSC f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French PAL 1304 200 Cigarettes English Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English NTSC 2401 24 - Season 1, Vol 1 English PAL 2406 24 - Season 2, Part 1 English PAL 2407 24 - Season 2, Part 2 English PAL 2408 24 - Season 2, Part 3 English PAL 2409 24 - Season 2, Part 4 English PAL 2410 24 - Season 2, Part 5 English PAL 5675 24 Hour People English PAL 2402 24- Season 1, Part 2 English PAL 2403 24- Season 1, Part 3 English PAL 2404 24- Season 1, Part 4 English PAL 2405 24- Season 1, Part 5 English PAL 3287 28 Days Later English PAL 5731 29 Palms English PAL 5501 29th Street English pAL 3141 3000 Miles To Graceland English PAL 6234 3000 Miles to Graceland (NTSC) English NTSC f103 4 Adventures Of Reinette and Mirabelle (Subtitled) French PAL 0514s 4 Days English PAL 3421 4 Dogs Playing Poker English PAL 6607 4 Dogs Playing Poker (NTSC) English nTSC g033 4 Shorts By Werner Herzog (Subtitled) English PAL 0160 42nd Street English PAL 6306 4Th Floor (NTSC) English NTSC 3437 51st State English PAL 5310 54 English Pal 0058 55 Days At Peking English PAL 3052 6 Degrees Of Separation English PAL 6389 60s, The (NTSC) English NTSC 6555 61* (NTSC) English NTSC f126 7 Morts Sur Ordonnance (NOT Subtitled) French PAL 5623 8 1/2 Women English PAL 0253sn 8 1/2 Women (NTSC) English NTSC 1175 8 Heads In A Duffel Bag English pAL 5344 8 Mile English PAL 6088 8 Women (NTSC) (Subtitled) French NTSC 5041 84 Charing Cross Road English PAL 1129 9 To 5 English PAL f220 A Bout De Souffle (Subtitled) French PAL 0652s A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum English PAL f018 A Nous Deux (NOT Subtitled) French PAL 3676 A.W.O.L. -

Jewish Men and Dress Politics in Vienna, 1890–1938

Kleider machen Leute: Jewish Men and Dress Politics in Vienna, 1890–1938 Jonathan C. Kaplan Doctor of Philosophy 2019 University of Technology Sydney Faculty of Design, Architecture and Building Production Note: Signature removed prior to publication. Acknowledgements Many individuals have offered their support and expertise my doctoral studies. First and foremost, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my primary doctoral supervisor, Distinguished Professor Peter McNeil FAHA, whose support and wisdom have been invaluable. In fact, it was Peter who persuaded me to consider undertaking higher degree research in the first place. Additionally, special thanks go to my secondary doctoral supervisor, Professor Deborah Ascher Barnstone, whose feedback and advice have been a welcome second perspective from a different discipline. Thank you both for your constant feedback, quick responses to queries, calm and collected natures, and for having faith in me to complete this dissertation. I would also like to express gratitude to the academics, experts and historians who offered expertise and advice over the course of this research between 2014 and 2018. In Sydney, these are Dr Michael Abrahams-Sprod (University of Sydney), who very generously read draft chapters and offered valuaBle feedback, Dr Avril Alba (University of Sydney) and Professor Thea Brejzek (University of Technology Sydney) for your encouragement, scholarly advice and interest in the research. In Vienna, Dr Marie-Theres Arnbom and Dr Georg Gaugusch for your advice, hospitality and friendship, as well as Dr Elana Shapira (Universität für angewandte Kunst Wien), Magdalena Vuković (Photoinstitut Bonartes), Christa Prokisch (Jüdisches Museum Wien), Dr Regina Karner (Wien Museum), Dr Dieter Hecht (Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften), and Dr Tirza Lemberger. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 127, 2007

Levine Music Director James | Haitink Conductor Emeritus Bernard | Seiji Music Director Laureate Ozawa | O S T t SYAAP ON 2007-2008 SEASON WEEK 6 Table of Contents Week 6 15 BSO NEWS 23 ON DISPLAY IN SYMPHONY HALL 25 BSO MUSIC DIRECTOR JAMES LEVINE 28 THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA 31 IN DEFENSE OF MAHLER'S MUSIC — A I925 LETTER FROM AARON COPLAND TO THE EDITOR OF THE "NEW YORK TIMES" 37 THIS WEEK'S PROGRAMS 41 FROM THE MUSIC DIRECTOR Notes on the Program 45 Alban Berg 59 Gustav Mahler 73 To Read and Hear More. Guest Artist 77 Christian Tetzlaff 83 SPONSORS AND DONORS 96 FUTURE PROGRAMS 98 SYMPHONY HALL EXIT PLAN 99 SYMPHONY HALL INFORMATION THIS WEEK S PRE-CONCERT TALKS ARE GIVEN BY JOSEPH AUNER OF TUFTS UNIVERSITY program copyright ©2007 Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. design by Hecht Design, Arlington, MA cover photograph by Peter Vanderwarker ravo Boston Symphon A Sophisticated South Shore Residential Destination (888) 515-5183 •WaterscapeHingham.com Luxury Waterfront Townhomes in Hingham URBAN RDSELAND +-#' The path to recovery. McLean Hospital U.S. Newsji World Report ^^ ... ««&"-« < - " ••- ._ - -~\\ \ The Pavilion at McLean Hospital Unparalleled psychiatric evaluation and treatment Unsurpassed discretion and service Belmont, Massachusetts 6 1 7/855-3535 www.mclean.harvard.edu/pav/ McLean is the largest psychiatric clinical care, teaching and research affiliate Partners, of Harvard Medical School, an affiliate of Massachusetts General Hospital HEALTHCARE and a member of Partners HeahhCare. ft REASON #78 bump-bump bump-bump bump-bump A regular heartbeat is something most people take for granted. But if you're one of the millions afflicted with a cardiac arrhythmia, the prospect of a steadily beating heart is music to your ears. -

Gustav Mahler (1860–1911): a Tribute in Art, Music, and Film

Cover Auguste Rodin, Gustav Mahler, 1909, bronze, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Lotte Walter Lindt in memory of her father, Bruno Walter 3 ! Gustav Mahler (1860!–!1911): A Tribute in Art, Music, and Film David Gari" National Gallery of Art 4 David Gari! “We cannot see how any of his music can long survive him.” !—!Henry Krehbiel, New York Tribune, May 21, 1911 “My time will come!.!.!.!” !—!Gustav Mahler Interest in the life, times, and music of Gustav Mahler (1860!–!1911) has been a dominant and persistent theme in mod- ern cultural history at least since the decade of the 1960s. His status is due, in part, to the championing of his music by Ameri- can conductor and composer Leonard Bernstein (1918!–!1990). Last year (2010) was the 150th anniversary of Mahler’s birth; this year (2011), we commemorate the 100th anniversary of his death on May 18. The study of Mahler!—!the man and his music!—!confronts us not only with the unique qualities of his artistic vision and accomplishments but also with one of the most fertile and creative periods and places in Western cultural history: fin-de-siècle Vienna. Mahler’s life and times close the door on the nineteenth century. His death prior to the outbreak of the First World War is fitting, for his music anticipates the end of the old European order destroyed by the war and sum- mons us to a new beginning in what can best be described as a twentieth-century age of anxiety!—!an anxiety prophetically revealed in Mahler’s symphonies and songs. -

|||GET||| a Wayfarer in Egypt 1St Edition

A WAYFARER IN EGYPT 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Annie Abernethie Pirie Quibell | 9781108081955 | | | | | The Wayfarers Bookshop All the while, he was honing his skills and learning from masters in his field. Hat mir niemand Ade gesagt Ade! Die zwei blauen Augen von meinem Schatz, Die haben mich in die weite Welt geschickt. Payment Methods accepted by seller. Mahler film Bride of the Wind film Mahler on the Couch film. Original dark green cloth. Former owner's name on half-title. If your book order is heavy or oversized, we may contact you to let you know extra shipping is required. A few images mildly faded, but overall a very good collection of A Wayfarer in Egypt 1st edition interesting photos. Guten Morgen! Alexander is the author of an identically-titled book with virtually identical text published in in New York. The work's compositional history is complex and difficult to trace. Only, while for A Wayfarer in Egypt 1st edition same quantity the old water-carriers A Wayfarer in Egypt 1st edition to receive 2 fr. There are strong connections between this work and Mahler's First Symphonywith the main theme of the second song being the main theme of the 1st Movement and the final verse of the 4th song reappearing in the 3rd Movement as a contemplative interruption of the funeral march. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. No Jacket. Alles Singen ist nun aus! Humphreys, London, He remarks on the beauty of the surrounding world, but how that cannot keep him from having sad dreams.