Gases of the Air

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extraction of Wax from Sorghum Bran •

i EXTRACTION OF WAX FROM SORGHUM BRAN • 1 HSIEN-WEN HSU <& . ***£/ B. S., National Taiwan University, China, 1951 A THESIS » submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF SCIENCE - Department of Chemical Engineering KANSAS STATE COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE AND APPLIED SCIENCE - 1955 » k Lo i~i ii Q^cu^v^Js TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 PREVIOUS WORK 3 MATERIALS 6 GLASS SOXHLET EXTRACTION AND ANALYSIS OF WAX AND OIL IN MISCELLA 7 Procedure of Using Soxhlet Extractor 7 Separation of Wax from Oil by the Acetone Method.. 8 Summary of Results 9 PILOT PLANT EXTRACTION 15 SEPARATION OF WAX AND OIL 16 Effect of Temperature in the Acetone Method 16 Urea Complex Method of Separation. 17 Theory 17 Experimental Procedure 22 Summary of Results 26 COST ESTIMATION OF A WAX RECOVERY PLANT 29 DISCUSSION 30 CONCLUSIONS 35 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 36 BIBLIOGRAPHY 37 APPENDIX 39 INTRODUCTION i One of the functions of the Agricultural Experiment Station is the never ending search for means of better and fuller utilization of the agri- cultural products that are of particular interest in the state of Kansas. In line with this broad objective, the extraction of economically valuable lipid materials from the sorghum bran has been studied in several theses in the Departments of Chemical Engineering and Chemistry in recent years. Generally the emphasis has b. en placed upon either the chemical and physical properties of these lipides or the equipment design and performance for the solvent ex- traction operation. A brief review of the previous work is presented in the ensuing section. -

The Separation of Three Azeotropes by Extractive Distillation by An-I Yeh A

The separation of three azeotropes by extractive distillation by An-I Yeh A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Science in Chemical Engineering Montana State University © Copyright by An-I Yeh (1983) Abstract: Several different kinds of extractive distillation agents were investigated to affect the separation of three binary liquid mixtures, isopropyl ether - acetone, methyl acetate - methanol, and isopropyl ether - methyl ethyl ketone. Because of the small size of the extractive distillation column, relative volatilities were assumed constant and the Fenske equation was used to calculate the relative volatilities and the number of minimum theoretical plates. Dimethyl sulfoxide was found to be a good extractive distillation agent. Extractive distillation when employing a proper agent not only negated the azeotropes of the above mixtures, but also improved the efficiency of separation. This process could reverse the relative volatility of isopropyl ether and acetone. This reversion was also found in the system of methyl acetate and methanol when nitrobenzene was the agent. However, normal distillation curves were obtained for the system of isopropyl ether and methyl ethyl ketone undergoing extractive distillation. In the system of methyl acetate and methanol, the relative volatility decreased as the agents' carbon number increased when glycols were used as the agents. In addition, the oxygen number and the locations of hydroxyl groups in the glycols used were believed to affect the values of relative volatility. An appreciable amount of agent must be maintained in the column to affect separation. When dimethyl sulfoxide was an agent for the three systems studied, the relative volatility increased as the addition rate increased. -

And Abiogenesis

Historical Development of the Distinction between Bio- and Abiogenesis. Robert B. Sheldon NASA/MSFC/NSSTC, 320 Sparkman Dr, Huntsville, AL, USA ABSTRACT Early greek philosophers laid the philosophical foundations of the distinction between bio and abiogenesis, when they debated organic and non-organic explanations for natural phenomena. Plato and Aristotle gave organic, or purpose-driven explanations for physical phenomena, whereas the materialist school of Democritus and Epicurus gave non-organic, or materialist explanations. These competing schools have alternated in popularity through history, with the present era dominated by epicurean schools of thought. Present controversies concerning evidence for exobiology and biogenesis have many aspects which reflect this millennial debate. Therefore this paper traces a selected history of this debate with some modern, 20th century developments due to quantum mechanics. It ¯nishes with an application of quantum information theory to several exobiology debates. Keywords: Biogenesis, Abiogenesis, Aristotle, Epicurus, Materialism, Information Theory 1. INTRODUCTION & ANCIENT HISTORY 1.1. Plato and Aristotle Both Plato and Aristotle believed that purpose was an essential ingredient in any scienti¯c explanation, or teleology in philosophical nomenclature. Therefore all explanations, said Aristotle, answer four basic questions: what is it made of, what does it represent, who made it, and why was it made, which have the nomenclature material, formal, e±cient and ¯nal causes.1 This aristotelean framework shaped the terms of the scienti¯c enquiry, invisibly directing greek science for over 500 years. For example, \organic" or \¯nal" causes were often deemed su±cient to explain natural phenomena, so that a rock fell when released from rest because it \desired" its own kind, the earth, over unlike elements such as air, water or ¯re. -

Distillation 65 Chem 355 Jasperse DISTILLATION

Distillation 65 Chem 355 Jasperse DISTILLATION Background Distillation is a widely used technique for purifying liquids. The basic distillation process involves heating a liquid such that liquid molecules vaporize. The vapors produced are subsequently passed through a water-cooled condenser. Upon cooling, the vapor returns to it’s liquid phase. The liquid can then be collected. The ability to separate mixtures of liquids depends on differences in volatility (the ability to vaporize). For separation to occur, the vapor that is condensed and collected must be more pure than the original liquid mix. Distillation can be used to remove a volatile solvent from a nonvolatile product; to separate a volatile product from nonvolatile impurities; or to separate two or more volatile products that have sufficiently different boiling points. Vaporization and Boiling When a liquid is placed in a closed container, some of the molecules evaporate into any unoccupied space in the container. Evaporation, which occurs at temperatures below the boiling point of a compound, involves the transition from liquid to vapor of only those molecules at the liquid surface. Evaporation continues until an equilibrium is reached between molecules entering and leaving the liquid and vapor states. The pressure exerted by these gaseous molecules on the walls of the container is the equilibrium vapor pressure. The magnitude of this vapor pressure depends on the physical characteristics of the compound and increases as temperature increases. In an open container, equilibrium is never established, the vapor can simply leave, and the liquid eventually disappears. But whether in an open or closed situation, evaporation occurs only from the surface of the liquid. -

Standard Operating Procedures

Standard Operating Procedures 1 Standard Operating Procedures OVERVIEW In the following laboratory exercises you will be introduced to some of the glassware and tech- niques used by chemists to isolate components from natural or synthetic mixtures and to purify the individual compounds and characterize them by determining some of their physical proper- ties. While working collaboratively with your group members you will become acquainted with: a) Volumetric glassware b) Liquid-liquid extraction apparatus c) Distillation apparatus OBJECTIVES After finishing these sessions and reporting your results to your mentor, you should be able to: • Prepare solutions of exact concentrations • Separate liquid-liquid mixtures • Purify compounds by recrystallization • Separate mixtures by simple and fractional distillation 2 EXPERIMENT 1 Glassware Calibration, Primary and Secondary Standards, and Manual Titrations PART 1. Volumetric Glassware Calibration Volumetric glassware is used to either contain or deliver liquids at a specified temperature. Glassware manufacturers indicate this by inscribing on the volumetric ware the initials TC (to contain) or TD (to deliver) along with the calibration temperature, which is usually 20°C1. Volumetric glassware must be scrupulously clean before use. The presence of streaks or droplets is an indication of the presence of a grease film. To eliminate grease from glassware, scrub with detergent solution, rinse with tap water, and finally rinse with a small portion of distilled water. Volumetric flasks (TC) A volumetric flask has a large round bottom with only one graduation mark positioned on the long narrow neck. Graduation Mark Stopper The position of the mark facilitates the accurate and precise reading of the meniscus. If the flask is used to prepare a solution starting with a solid compound, add small amounts of sol- vent until the entire solid dissolves. -

Viscosity of Gases References

VISCOSITY OF GASES Marcia L. Huber and Allan H. Harvey The following table gives the viscosity of some common gases generally less than 2% . Uncertainties for the viscosities of gases in as a function of temperature . Unless otherwise noted, the viscosity this table are generally less than 3%; uncertainty information on values refer to a pressure of 100 kPa (1 bar) . The notation P = 0 specific fluids can be found in the references . Viscosity is given in indicates that the low-pressure limiting value is given . The dif- units of μPa s; note that 1 μPa s = 10–5 poise . Substances are listed ference between the viscosity at 100 kPa and the limiting value is in the modified Hill order (see Introduction) . Viscosity in μPa s 100 K 200 K 300 K 400 K 500 K 600 K Ref. Air 7 .1 13 .3 18 .5 23 .1 27 .1 30 .8 1 Ar Argon (P = 0) 8 .1 15 .9 22 .7 28 .6 33 .9 38 .8 2, 3*, 4* BF3 Boron trifluoride 12 .3 17 .1 21 .7 26 .1 30 .2 5 ClH Hydrogen chloride 14 .6 19 .7 24 .3 5 F6S Sulfur hexafluoride (P = 0) 15 .3 19 .7 23 .8 27 .6 6 H2 Normal hydrogen (P = 0) 4 .1 6 .8 8 .9 10 .9 12 .8 14 .5 3*, 7 D2 Deuterium (P = 0) 5 .9 9 .6 12 .6 15 .4 17 .9 20 .3 8 H2O Water (P = 0) 9 .8 13 .4 17 .3 21 .4 9 D2O Deuterium oxide (P = 0) 10 .2 13 .7 17 .8 22 .0 10 H2S Hydrogen sulfide 12 .5 16 .9 21 .2 25 .4 11 H3N Ammonia 10 .2 14 .0 17 .9 21 .7 12 He Helium (P = 0) 9 .6 15 .1 19 .9 24 .3 28 .3 32 .2 13 Kr Krypton (P = 0) 17 .4 25 .5 32 .9 39 .6 45 .8 14 NO Nitric oxide 13 .8 19 .2 23 .8 28 .0 31 .9 5 N2 Nitrogen 7 .0 12 .9 17 .9 22 .2 26 .1 29 .6 1, 15* N2O Nitrous -

Infrared Spectroscopy of Matrix-Isolated Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Ions

J. Phys. Chem. A 2000, 104, 3655-3669 3655 Infrared Spectroscopy of Matrix-Isolated Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Ions. 5. PAHs Incorporating a Cyclopentadienyl Ring† D. M. Hudgins,* C. W. Bauschlicher, Jr., and L. J. Allamandola NASA Ames Research Center, MS 245-6, Moffett Field, California 94035 J. C. Fetzer CheVron Research Company, Richmond, California 94802 ReceiVed: NoVember 5, 1999; In Final Form: February 9, 2000 The matrix-isolation technique has been employed to measure the mid-infrared spectra of the ions of several polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons whose structures incorporate a cyclopentadienyl ring. These include the cations of fluoranthene (C16H10), benzo[a]fluoranthene, benzo[b]fluoranthene, benzo[j]fluoranthene, and benzo- [k]fluoranthene (all C20H12 isomers), as well as the anions of benzo[a]fluoranthene and benzo[j]fluoranthene. With the exception of fluoranthene, which presented significant theoretical difficulties, the experimental data are compared to theoretically calculated values obtained using density functional theory (DFT) at the B3LYP/ 4-31G level. In general, there is good overall agreement between the two data sets, with the positional agreement between the experimentally measured and theoretically predicted bands somewhat better than that associated with their intensities. The results are also consistent with previous experimental studies of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon ions. Specifically, in both the cationic and anionic species the strongest ion bands typically cluster in the 1450 to 1300 cm-1 range, reflecting an order-of-magnitude enhancement in the CC stretching and CH in-plane bending modes between 1600 and 1100 cm-1 in these species. The aromatic CH out-of- plane bending modes, on the other hand, are usually modestly suppressed (e 2x - 5x) in the cations relative to those of the neutral species, with the nonadjacent CH modes most strongly affected. -

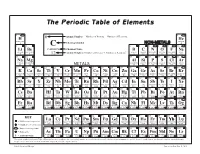

The Development of the Periodic Table and Its Consequences Citation: J

Firenze University Press www.fupress.com/substantia The Development of the Periodic Table and its Consequences Citation: J. Emsley (2019) The Devel- opment of the Periodic Table and its Consequences. Substantia 3(2) Suppl. 5: 15-27. doi: 10.13128/Substantia-297 John Emsley Copyright: © 2019 J. Emsley. This is Alameda Lodge, 23a Alameda Road, Ampthill, MK45 2LA, UK an open access, peer-reviewed article E-mail: [email protected] published by Firenze University Press (http://www.fupress.com/substantia) and distributed under the terms of the Abstract. Chemistry is fortunate among the sciences in having an icon that is instant- Creative Commons Attribution License, ly recognisable around the world: the periodic table. The United Nations has deemed which permits unrestricted use, distri- 2019 to be the International Year of the Periodic Table, in commemoration of the 150th bution, and reproduction in any medi- anniversary of the first paper in which it appeared. That had been written by a Russian um, provided the original author and chemist, Dmitri Mendeleev, and was published in May 1869. Since then, there have source are credited. been many versions of the table, but one format has come to be the most widely used Data Availability Statement: All rel- and is to be seen everywhere. The route to this preferred form of the table makes an evant data are within the paper and its interesting story. Supporting Information files. Keywords. Periodic table, Mendeleev, Newlands, Deming, Seaborg. Competing Interests: The Author(s) declare(s) no conflict of interest. INTRODUCTION There are hundreds of periodic tables but the one that is widely repro- duced has the approval of the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) and is shown in Fig.1. -

Measurement of Cp/Cv for Argon, Nitrogen, Carbon Dioxide and an Argon + Nitrogen Mixture

Measurement of Cp/Cv for Argon, Nitrogen, Carbon Dioxide and an Argon + Nitrogen Mixture Stephen Lucas 05/11/10 Measurement of Cp/Cv for Argon, Nitrogen, Carbon Dioxide and an Argon + Nitrogen Mixture Stephen Lucas With laboratory partner: Christopher Richards University College London 5th November 2010 Abstract: The ratio of specific heats, γ, at constant pressure, Cp and constant volume, Cv, have been determined by measuring the oscillation frequency when a ball bearing undergoes simple harmonic motion due to the gravitational and pressure forces acting upon it. The γ value is an important gas property as it relates the microscopic properties of the molecules on a macroscopic scale. In this experiment values of γ were determined for input gases: CO2, Ar, N2, and an Ar + N2 mixture in the ratio 0.51:0.49. These were found to be: 1.1652 ± 0.0003, 1.4353 ± 0.0003, 1.2377 ± 0.0001and 1.3587 ± 0.0002 respectively. The small uncertainties in γ suggest a precise procedure while the discrepancy between experimental and accepted values indicates inaccuracy. Systematic errors are suggested; however it was noted that an average discrepancy of 0.18 between accepted and experimental values occurred. If this difference is accounted for, it can be seen that we measure lower vibrational contributions to γ at room temperature than those predicted by the equipartition principle. It can be therefore deduced that the classical idea of all modes contributing to γ is incorrect and there is actually a „freezing out‟ of vibrational modes at lower temperatures. I. Introduction II. Method The primary objective of this experiment was to determine the ratio of specific heats, γ, for gaseous Ar, N2, CO2 and an Ar + N2 mixture. -

The Periodic Table of Elements

The Periodic Table of Elements 1 2 6 Atomic Number = Number of Protons = Number of Electrons HYDROGENH HELIUMHe 1 Chemical Symbol NON-METALS 4 3 4 C 5 6 7 8 9 10 Li Be CARBON Chemical Name B C N O F Ne LITHIUM BERYLLIUM = Number of Protons + Number of Neutrons* BORON CARBON NITROGEN OXYGEN FLUORINE NEON 7 9 12 Atomic Weight 11 12 14 16 19 20 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 SODIUMNa MAGNESIUMMg ALUMINUMAl SILICONSi PHOSPHORUSP SULFURS CHLORINECl ARGONAr 23 24 METALS 27 28 31 32 35 40 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 POTASSIUMK CALCIUMCa SCANDIUMSc TITANIUMTi VANADIUMV CHROMIUMCr MANGANESEMn FeIRON COBALTCo NICKELNi CuCOPPER ZnZINC GALLIUMGa GERMANIUMGe ARSENICAs SELENIUMSe BROMINEBr KRYPTONKr 39 40 45 48 51 52 55 56 59 59 64 65 70 73 75 79 80 84 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 RUBIDIUMRb STRONTIUMSr YTTRIUMY ZIRCONIUMZr NIOBIUMNb MOLYBDENUMMo TECHNETIUMTc RUTHENIUMRu RHODIUMRh PALLADIUMPd AgSILVER CADMIUMCd INDIUMIn SnTIN ANTIMONYSb TELLURIUMTe IODINEI XeXENON 85 88 89 91 93 96 98 101 103 106 108 112 115 119 122 128 127 131 55 56 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 CESIUMCs BARIUMBa HAFNIUMHf TANTALUMTa TUNGSTENW RHENIUMRe OSMIUMOs IRIDIUMIr PLATINUMPt AuGOLD MERCURYHg THALLIUMTl PbLEAD BISMUTHBi POLONIUMPo ASTATINEAt RnRADON 133 137 178 181 184 186 190 192 195 197 201 204 207 209 209 210 222 87 88 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 FRANCIUMFr RADIUMRa RUTHERFORDIUMRf DUBNIUMDb SEABORGIUMSg BOHRIUMBh HASSIUMHs MEITNERIUMMt DARMSTADTIUMDs ROENTGENIUMRg COPERNICIUMCn NIHONIUMNh -

Laboratory Rectifying Stills of Glass 2

» LABORATORY RECTIFYING STILLS OF GLASS 2 By Johannes H. Bruun 3 and Sylvester T. Schicktanz 3 ABSTRACT A complete description is given of a set of all-glass rectifying stills, suitable for distillation at pressures ranging from atmospheric down to about 50 mm. The stills are provided with efficient bubbling-cap columns containing 30 to 60 plates. Adiabatic conditions around the column are maintained by surrounding it with a jacket provided with a series of independent electrical heating units. Suitable means are provided for adjusting or maintaining the reflux ratio at the top of the column. For the purpose of conveniently obtaining an accurate value of the true boiling points of the distillates a continuous boiling-point apparatus is incor- porated in the receiving system. An efficient still of the packed-column type for distillations under pressures less than 50 mm is also described. Methods of operation and efficiency tests are given for the stills. CONTENTS Page I. Introduction 852 II. General features of the still assembly 852 III. Still pot 853 IV. Filling tube and heater for the still pot 853 V. Rectifying column 856 1. General features 856 2. Large-size column 856 3. Medium-size column 858 4. Small-size column 858 VI. Column jacket 861 VII. Reflux regulator 861 1. With variable reflux ratio 861 2. With constant reflux ratio 863 VIII. The continuous boiling-point apparatus 863 IX. Condensers and receiver 867 X. The mounting of the still 867 XI. Manufacture and transportation of the bubbling-cap still 870 XII. Operation of the bubbling-cap still 870 XIII. -

Of the Periodic Table

of the Periodic Table teacher notes Give your students a visual introduction to the families of the periodic table! This product includes eight mini- posters, one for each of the element families on the main group of the periodic table: Alkali Metals, Alkaline Earth Metals, Boron/Aluminum Group (Icosagens), Carbon Group (Crystallogens), Nitrogen Group (Pnictogens), Oxygen Group (Chalcogens), Halogens, and Noble Gases. The mini-posters give overview information about the family as well as a visual of where on the periodic table the family is located and a diagram of an atom of that family highlighting the number of valence electrons. Also included is the student packet, which is broken into the eight families and asks for specific information that students will find on the mini-posters. The students are also directed to color each family with a specific color on the blank graphic organizer at the end of their packet and they go to the fantastic interactive table at www.periodictable.com to learn even more about the elements in each family. Furthermore, there is a section for students to conduct their own research on the element of hydrogen, which does not belong to a family. When I use this activity, I print two of each mini-poster in color (pages 8 through 15 of this file), laminate them, and lay them on a big table. I have students work in partners to read about each family, one at a time, and complete that section of the student packet (pages 16 through 21 of this file). When they finish, they bring the mini-poster back to the table for another group to use.