Me Chalet School and the Lintons 1934 11

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REFERENCE DOCUMENT Containing the Annual Financial Report Fiscal Year 2016 PROFILE

REFERENCE DOCUMENT containing the Annual Financial Report Fiscal Year 2016 PROFILE The Lagardère group is a global leader in content publishing, production, broadcasting and distribution, whose powerful brands leverage its virtual and physical networks to attract and enjoy qualifi ed audiences. The Group’s business model relies on creating a lasting and exclusive relationship between the content it offers and its customers. It is structured around four business divisions: • Books and e-Books: Lagardère Publishing • Travel Essentials, Duty Free & Fashion, and Foodservice: Lagardère Travel Retail • Press, Audiovisual (Radio, Television, Audiovisual Production), Digital and Advertising Sales Brokerage: Lagardère Active • Sponsorship, Content, Consulting, Events, Athletes, Stadiums, Shows, Venues and Artists: Lagardère Sports and Entertainment 1945: at the end of World 1986: Hachette regains 26 March 2003: War II, Marcel Chassagny founds control of Europe 1. Arnaud Lagardère is appointed Matra (Mécanique Aviation Managing Partner of TRAction), a company focused 10 February 1988: Lagardère SCA. on the defence industry. Matra is privatised. 2004: the Group acquires 1963: Jean-Luc Lagardère 30 December 1992: a portion of Vivendi Universal becomes Chief Executive Publishing’s French and following the failure of French Offi cer of Matra, which Spanish assets. television channel La Cinq, has diversifi ed into aerospace Hachette is merged into Matra and automobiles. to form Matra-Hachette, 2007: the Group reorganises and Lagardère Groupe, a French around four major institutional 1974: Sylvain Floirat asks partnership limited by shares, brands: Lagardère Publishing, Jean-Luc Lagardère to head is created as the umbrella Lagardère Services (which the Europe 1 radio network. company for the entire became Lagardère Travel Retail ensemble. -

'Pinkoes Traitors'

‘PINKOES AND TRAITORS’ The BBC and the nation, 1974–1987 JEAN SEATON PROFILE BOOKS First published in Great Britain in !#$% by Pro&le Books Ltd ' Holford Yard Bevin Way London ()$* +,- www.pro lebooks.com Copyright © Jean Seaton !#$% The right of Jean Seaton to be identi&ed as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright Designs and Patents Act $++/. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN +4/ $ /566/ 545 6 eISBN +4/ $ /546% +$6 ' All reasonable e7orts have been made to obtain copyright permissions where required. Any omissions and errors of attribution are unintentional and will, if noti&ed in writing to the publisher, be corrected in future printings. Text design by [email protected] Typeset in Dante by MacGuru Ltd [email protected] Printed and bound in Britain by Clays, Bungay, Su7olk The paper this book is printed on is certi&ed by the © $++6 Forest Stewardship Council A.C. (FSC). It is ancient-forest friendly. The printer holds FSC chain of custody SGS-COC-!#6$ CONTENTS List of illustrations ix Timeline xvi Introduction $ " Mrs Thatcher and the BBC: the Conservative Athene $5 -

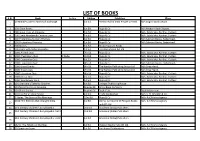

List of Books S.N

LIST OF BOOKS S.N. Book Author Edition Publisher Place 10 Minute Guide to Microsoft Exchange. 1st Ed. Prentic-Hall of India Private Limited. M/s English Book Depot 1 2 100 Great Books. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s Modern Book Depote, 3 100 Great Lives of Antiquity. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 4 100 Great Nineteenth Century Lives. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 5 100 Pretentious Nursery Rhymes. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s Sabnam Books, Badambadi, 6 100 Pretentious Proverbs. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s Sabnam Books, Badambadi, 7 100 Stories. 1st Ed. Better Yourself Books 8 100 Years with Nobel Laureates. 1st Ed. I K International Pvt Ltd 9 1000 Animal Quiz. 7th Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 10 1000 Chemistery Quiz. C Dube 3rd Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 11 1000 Economics Quiz. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 12 1000 Economics Quiz. 4th Ed. Rupa & Co M/s Sabnam Books, Badambadi, 13 1000 Great Events. 6th Ed. The Hamlyn Publishing Group Ltd. M/s Dreamland, 14 1000 Great Lives. 7th Ed. The Hamlyn Publishing Group Ltd. M/s Dreamland, 15 1000 Literature Quiz. 4th Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 16 1000 Orissa Quiz. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 17 1000 Wordpower Quiz. 1st Ed. Rupa & Co M/s. Sabdaloka, Ranihat, Cuttack 18 101 Grandma's Tales for Children. 1st Ed. Dhingra Publishing House 19 101 Moral Stories of Grandpa. -

Ull History Centre: Papers of Alan Plater

Hull History Centre: Papers of Alan Plater U DPR Papers of Alan Plater 1936-2012 Accession number: 1999/16, 2004/23, 2013/07, 2013/08, 2015/13 Biographical Background: Alan Frederick Plater was born in Jarrow in April 1935, the son of Herbert and Isabella Plater. He grew up in the Hull area, and was educated at Pickering Road Junior School and Kingston High School, Hull. He then studied architecture at King's College, Newcastle upon Tyne, becoming an Associate of the Royal Institute of British Architects in 1959 (since lapsed). He worked for a short time in the profession, before becoming a full-time writer in 1960. His subsequent career has been extremely wide-ranging and remarkably successful, both in terms of his own original work, and his adaptations of literary works. He has written extensively for radio, television, films and the theatre, and for the daily and weekly press, including The Guardian, Punch, Listener, and New Statesman. His writing credits exceed 250 in number, and include: - Theatre: 'A Smashing Day'; 'Close the Coalhouse Door'; 'Trinity Tales'; 'The Fosdyke Saga' - Film: 'The Virgin and the Gypsy'; 'It Shouldn't Happen to a Vet'; 'Priest of Love' - Television: 'Z Cars'; 'The Beiderbecke Affair'; 'Barchester Chronicles'; 'The Fortunes of War'; 'A Very British Coup'; and, 'Campion' - Radio: 'Ted's Cathedral'; 'Tolpuddle'; 'The Journal of Vasilije Bogdanovic' - Books: 'The Beiderbecke Trilogy'; 'Misterioso'; 'Doggin' Around' He received numerous awards, most notably the BAFTA Writer's Award in 1988. He was made an Honorary D.Litt. of the University of Hull in 1985, and was made a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 1985. -

20Entrepreneurial Journalism

Journalism: New Challenges Edited by: Karen Fowler-Watt and Stuart Allan Journalism: New Challenges Edited by: Karen Fowler-Watt and Stuart Allan Published by: Centre for Journalism & Communication Research Bournemouth University ISBN: 978-1-910042-01-4 [paperback] ISBN: 978-1-910042-00-7 [ebook-PDF] ISBN: 978-1-910042-02-1 [ebook-epub] http://microsites.bournemouth.ac.uk/cjcr/ Copyright © 2013 Acknowledgements Table of contents Introduction Karen Fowler-Watt and Stuart Allan Section One: New Directions in Journalism 1 A Perfect Storm 1 Stephen Jukes 2 The Future of Newspapers in a Digital Age 19 Shelley Thompson 3 International News Agencies: Global Eyes 35 that Never Blink Phil MacGregor 4 Impartiality in the News 64 Sue Wallace 5 Current Affairs Radio: Realigning News and 79 Comment Hugh Chignell 6 Radio Interviews: A Changing Art 98 Ceri Thomas 7 The Changing Landscape of Magazine 114 Journalism Emma Scattergood 8 Live Blogging and Social Media Curation 123 Einar Thorsen 9 Online News Audiences: The Challenges 146 of Web Metrics An Nguyen ii Table of contents 10 The Camera as Witness: The Changing 162 Nature of Photojournalism Stuart Allan and Caitlin Patrick Section Two: The Changing Nature of News Reporting 11 Truth and the Tabloids 183 Adam Lee – Potter 12 Irreverence and Independence? The Press 192 post–Leveson Sandra Laville 13 Editorial Leadership in the Newsroom 201 Karen Fowler-Watt and Andrew Wilson 14 Investigative Journalism: Secrets, Salience 220 and Storytelling Kevin Marsh 15 Journalists and their Sources: The Twin 241 Challenges of Diversity and Verification Jamie Matthews 16 News and Public Relations: A Dangerous 258 Relationship Kevin Moloney, Dan Jackson and David McQueen 17 Political Reporting: Enlightening Citizens 281 or Undermining Democracy? Darren G. -

A Writer's Calendar

A WRITER’S CALENDAR Compiled by J. L. Herrera for my mother and with special thanks to Rose Brown, Peter Jones, Eve Masterman, Yvonne Stadler, Marie-France Sagot, Jo Cauffman, Tom Errey and Gianni Ferrara INTRODUCTION I began the original calendar simply as a present for my mother, thinking it would be an easy matter to fill up 365 spaces. Instead it turned into an ongoing habit. Every time I did some tidying up out would flutter more grubby little notes to myself, written on the backs of envelopes, bank withdrawal forms, anything, and containing yet more names and dates. It seemed, then, a small step from filling in blank squares to letting myself run wild with the myriad little interesting snippets picked up in my hunting and adding the occasional opinion or memory. The beginning and the end were obvious enough. The trouble was the middle; the book was like a concertina — infinitely expandable. And I found, so much fun had the exercise become, that I was reluctant to say to myself, no more. Understandably, I’ve been dependent on other people’s memories and record- keeping and have learnt that even the weightiest of tomes do not always agree on such basic ‘facts’ as people’s birthdays. So my apologies for the discrepancies which may have crept in. In the meantime — Many Happy Returns! Jennie Herrera 1995 2 A Writer’s Calendar January 1st: Ouida J. D. Salinger Maria Edgeworth E. M. Forster Camara Laye Iain Crichton Smith Larry King Sembene Ousmane Jean Ure John Fuller January 2nd: Isaac Asimov Henry Kingsley Jean Little Peter Redgrove Gerhard Amanshauser * * * * * Is prolific writing good writing? Carter Brown? Barbara Cartland? Ursula Bloom? Enid Blyton? Not necessarily, but it does tend to be clear, simple, lucid, overlapping, and sometimes repetitive. -

Independent Television Producers in England

Negotiating Dependence: Independent Television Producers in England Karl Rawstrone A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of the West of England, Bristol for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Arts and Creative Industries, University of the West of England, Bristol November 2020 77,900 words. Abstract The thesis analyses the independent television production sector focusing on the role of the producer. At its centre are four in-depth case studies which investigate the practices and contexts of the independent television producer in four different production cultures. The sample consists of a small self-owned company, a medium- sized family-owned company, a broadcaster-owned company and an independent- corporate partnership. The thesis contextualises these case studies through a history of four critical conjunctures in which the concept of ‘independence’ was debated and shifted in meaning, allowing the term to be operationalised to different ends. It gives particular attention to the birth of Channel 4 in 1982 and the subsequent rapid growth of an independent ‘sector’. Throughout, the thesis explores the tensions between the political, economic and social aims of independent television production and how these impact on the role of the producer. The thesis employs an empirical methodology to investigate the independent television producer’s role. It uses qualitative data, principally original interviews with both employers and employees in the four companies, to provide a nuanced and detailed analysis of the complexities of the producer’s role. Rather than independence, the thesis uses network analysis to argue that a television producer’s role is characterised by sets of negotiated dependencies, through which professional agency is exercised and professional identity constructed and performed. -

The Transformative Energy of Children's Literature

Notes 1 Breaking Bounds: The Transformative Energy of Children’s Literature 1. I do not recognise Karin Lesnik-Oberstein’s insistence that the majority of academics who write about children’s literature are primarily concerned with finding the right book for the right child (Children’s Literature: New Approaches, 2004: 1–24). 2. Although publishing for children includes many innovative and important non- fictional works, my concern is specifically with narrative fictions for children. 3. See Rumer Godden’s entertaining ‘An Imaginary Correspondence’ featuring invented letters between Mr V. Andal, an American publisher working for the De Base Publishing Company, and Beatrix Potter for an entertaining insight into this process. The piece appeared in Horn Book Magazine 38 (August 1963), 197–206. 4. Peter Hunt raises questions about the regard accorded to Hughes’s writing for children suggesting that it derives more from the insecurity of children’s literature critics than the quality of the work: ‘It is almost as if, with no faith in their own judgements, such critics are glad to accept the acceptance of an accepted poet’ (2001: 79–81). 5. See Reynolds and Tucker, 1998; Trites, 2000 and Lunden, 2004. 6. Although writing in advance of Higonnet, Rose would have been familiar with many of the examples on which Pictures of Innocence is based. 7. By the time she reaches her conclusion, Rose has modified her position to empha- sise that ‘children’s literature is just one of the areas in which this fantasy is played out’ (138), undermining her claims that the child-audience is key to the work of children’s literature in culture. -

*^" •'•"Jsbfc''""^.' •'' '"'V^F' F'7"''^^?!CT

*^" •'•"JSBfc''""^.' •'' '"'V^f' f'7"''^^?!CT 1 AJR Information Volume XLV No. 1 January 1990 £3 (to non-members) Don't miss £4m needed to extend the Homes Back to the future P-3 AJR residential care appeal Sir Sigmund Sternberg visits Help us to meet the challenge Day Centre p. 8 he AJR together with CBF Residendal Care and Housing Association have risen to the challenge AJR Residential of the 1990s and beyond with the preparadon of a five year plan for extending and refurbishing Care Appeal - the homes, whose history now goes back more than thirty years. The plan provides for: How to T contribute . * 21 new sheltered accommodation units P-9 * 13 new rooms with toilet facilities * 102 rooms to be provided with toilet facilides * 15 rooms to offer nursing facilities The AJR through its AJR Charitable Trust has undertaken responsibility for mounnng the appeal to raise the funds for this project. Moreover, in order to permit an immediate start on the implementation of the plan the Trust has underwritten the first £500 000 of the cost. Thus work has already started on the first phase. Higher expectations Our homes offer sheltered accommodation, residendal care and full nursing care for about 250 people, a considerable number, but not enough to meet current needs. They have been shining examples of their kind, comparing favourably with others around the country. But higher standards are now expected, which means that new rooms must be built with private toilets and showers, and these facilities must be added to existing rooms. Residents are now older at the time of admission and average age in the homes has risen to 85. -

Milestonesofmannedflight World

' J/ILESTONES of JfANNED i^LIGHT With a short dash down the runway, the machine lifted into the air and was flying. It was only a flight of twelve seconds, and it was an uncertain, waiy. creeping sort offlight at best: but it was a realflight at last and not a glide. ORV1U.E VPRK.HT A DIRECT RESULT OF OnUle Wright's intrepid 12- second A flight on Kill Devil Hill in 1903. mankind, in the space of just nine decades, has developed the means to leave the boundaries of Earth, visit space and return. As a matter of routine, even- )ear millions of business people and tourists travel to the furthest -^ reaches of our planet within a matter of hours - some at twice the speed of sound. The progress has, quite simpl) . been astonishing. Having discovered the means of controlled flight in a powered, heavier-than-air machine, other uses than those of transpon were inevitable and research into the militan- potential of manned flight began almost immediatel>-. The subsequent effect of aviation on warfare has been nothing shon of revolutionary', and in most of the years since 1903 the leading technological innovations have resulted from militan- research programs. In Milestones of Manned Flight, aviation expen Mike .Spick has selected the -iO-plus events, both civil and militan-, which he considers to mark the most significant points of aviation histon-. Each one is illustrated, and where there have been significant related developments from that particular milestone, then these are featured too. From the intrepid and pioneering Wright brothers to the high-technology' gurus developing the F-22 Advanced Tactical Fighter, the histon' of manned flight is. -

Document De Référence 2016 Lagardère

DOCUMENT DE RÉFÉRENCE contenant un Rapport fi nancier annuel Exercice 2016 PROFIL Le groupe Lagardère est un des leaders mondiaux de l’édition, la production, la diffusion et la distribution de contenus dont les marques fortes génèrent et rencontrent des audiences qualifi ées grâce à ses réseaux virtuels et physiques. Son modèle repose sur la création d’une relation durable et exclusive entre ses contenus et les consommateurs. Il se structure autour de quatre branches d’activités : • Livre et Livre numérique : Lagardère Publishing • Travel Essentials, Duty Free & Fashion et Foodservice : Lagardère Travel Retail • Presse, Audiovisuel (Radio, TV, Production audiovisuelle), Digital et Régie publicitaire : Lagardère Active • Sponsoring, Contenus, Conseil, Événements, Athlètes, Stades, Spectacles, Salles et Artistes : Lagardère Sports and Entertainment 1945 : après la Libération, 1986 : reprise du contrôle 26 mars 2003 : Arnaud création par Marcel Chassagny d’Europe 1 par Hachette. Lagardère est nommé Gérant de la société Matra (Mécanique de Lagardère SCA. Aviation TRAction), spécialisée 10 février 1988 : dans le domaine militaire. privatisation de Matra. 2004 : acquisition d’une partie des actifs français et 1963 : Jean-Luc Lagardère 30 décembre 1992 : espagnols du groupe d’édition est nommé Directeur Général Vivendi Universal Publishing. après l’échec de La Cinq, de la société Matra dont les création de Matra Hachette activités se sont diversifi ées suite à la fusion-absorption 2007 : rebranding du Groupe dans l'aérospatiale et de Hachette par Matra, et autour de quatre grandes l'automobile. de Lagardère Groupe, société marques institutionnelles : faîtière de l’ensemble du Lagardère Publishing, 1974 : Sylvain Floirat confi e la Groupe qui adopte le statut Lagardère Services (devenue direction d’Europe 1 à Jean-Luc juridique de société en Lagardère Travel Retail en 2015), Lagardère. -

BA-Thesis the Emerge of a 2-Dimensional Global Society

BA-thesis Sociology The emerge of a 2-dimensional global society The exploitation of the social media, herd behaviour, moral panics and the 5th estate Muhammed Emin Kizilkaya Viðar Halldórsson January 2018 The emerge of a 2-dimensional global society The exploitation of the social media, herd behavior, moral panics and the 5th estate Muhammed Emin Kizilkaya Final project for BA-degree in Sociology Supervisor: Viðar Halldórsson 12 ECTS Faculty of Social Sciences of the University of Iceland January, 2018 2 Cohesion and fragmentation In the fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of BA in Sociology it is forbidden to copy this thesis without the author’s permission © Muhammed Emin Kizilkaya, 2018 3 Abstract We live in a 2-dimensional global society divided between the physical world and the virtual world both representing the social reality but constructed into different norms and standards, that each defines the contemporary post-modern information society that we all globally have become a part of. This thesis gives an abstract overview of the significant determination of the virtual world implying different perspectives on everything from micro to macro, from social to political, from mental to biological with the intention of broadening the attention on sudden societal transformation as a function of rapid technological processes. Excluding the virtual world when analysing the behaviour of individuals in all global societies increases the possibility of research bias as technology has become the society today. The new virtual world has become a more significant agent of change than the physical world and this new world should never be taken for granted.