FOLKSONG RESEARCII and NATIONAL IDENTITY in WEST GERMANY, Ig4g-Ig7o

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Savage and Brown Final Except Pp

Toward a New Comparative Musicology Patrick E. Savage and Steven Brown omparative musicology is the academic discipline devoted to the comparative C study of music. It looks at music (broadly defined) in all of its forms across all cultures throughout time, including related phenomena in language, dance, and animal communication. As with its sister discipline of comparative linguistics, comparative musicology seeks to classify the musics of the world into stylistic families, describe the geographic distribution of these styles, elucidate universal trends in musics across cultures, and understand the causes and mechanisms shaping the biological and cultural evolution of music. While most definitions of comparative musicology put forward over the years have been limited to the study of folk and/or non-Western musics (Merriam 1977), we envision this field as an inclusive discipline devoted to the comparative study of all music, just as the name implies. The intellectual and political history of comparative musicology and its modern- day successor, ethnomusicology, is too complex to review here. It has been detailed in a number of key publications—most notably by Merriam (1964, 1977, 1982) and Nettl (2005; Nettl and Bohlman 1991)—and succinctly summarized by Toner (2007). Comparative musicology flourished during the first half of the twentieth century, and was predicated on the notion that the cross-cultural analysis of musics could shed light on fundamental questions about human evolution. But after World War II—and in large part because of it—a new field called ethnomusicology emerged in the United States based on Toward a New Comparative Musicology the paradigms of cultural anthropology. -

What Are the Great Discoveries of Your Field?

International Journal of Education & the Arts Editors Christine Marmé Thompson S. Alex Ruthmann Pennsylvania State University University of Massachusetts Lowell Eeva Anttila William J. Doan Theatre Academy Helsinki Pennsylvania State University http://www.ijea.org/ ISS1: 1529-8094 Volume 14 Special Issue 1.3 January 30, 2013 What $re the *reat 'iscoveries of <our )ield? Bruno Nettl University of Illinois, USA Citation: Nettl, B. (2013). What are the great discoveries of your field? International Journal of Education & the Arts, 14(SI 1.3). Retrieved [date] from http://www.ijea.org/v14si1/. IJEA Vol. 14 Special Issue 1.3 - http://www.ijea.org/v14si1/ 2 Introduction Ethnomusicology, the field in which I've spent most of my life, is an unpronounceable interdisciplinary field whose denizens have trouble agreeing on its definition. I'll just call it the study of the world’s musical cultures from a comparative perspective, and the study of all music from the perspective of anthropology. Now, I have frequently found myself surrounded by colleagues in other fields who wanted me to explain what I'm all about, and so I have tried frequently, and really without much success, to find the right way to do this. Again, not long go, at a dinner, a distinguished physicist and music lover, trying, I think, to wrap his mind around what I was doing, asked me, "What are the great discoveries of your field?" I don't think he was being frivolous, but he saw his field as punctuated by Newton, Einstein, Bardeen, and he wondered whether we had a similar set of paradigms, or perhaps of sacred figures. -

Book Reviews

Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, Vol. 42(3), 279–280 Summer 2006 Published online in Wiley Interscience (www.interscience.wiley.com). DOI 10.1002 /jhbs.20173 © 2006 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. BOOK REVIEWS D. Brett King and Michael Wertheimer. Max Wertheimer and Gestalt Theory. New Brunswick, NJ, and London: Transaction Publishers, 2005. 438 pp. $49.95. ISBN: 0- 7658-0258-9. To review this long-awaited volume is a delicate task. Full disclosure up front: I have known and liked Michael Wertheimer for more than 30 years, since I first began my own work on the history of Gestalt theory. I was privileged to work with the Max Wertheimer papers in the mid-1970s, when they were still stored in Michael Wertheimer’s home in Boulder, Colorado. At that time, Michael Wertheimer already planned to write a biography of his father. The finished book, written with the help of D. Brett King, can only be called a labor of love. This is a fascinating, comprehensive, generally well-written, and, above all, warm- hearted volume. The authors make every effort to give both the person and his creation their due. As might be expected, Wertheimer’s family life gets detailed attention. The authors make judicious use of an extended interview with Max Wertheimer’s former wife and Michael Wertheimer’s mother, Anni Wertheimer Hornbostel, and other family documents, including a newspaper “published” by the Wertheimer children. And Michael Wertheimer contributes his own memories of his father, helping to make him come alive on the page. Max Wertheimer’s -

American Experimental Music in West Germany from the Zero Hour To

Beal_Text 12/12/05 5:50 PM Page 8 one The American Occupation and Agents of Reeducation 1945-1950 henry cowell and the office of war information Between the end of World War I and the advent of the Third Reich, many American composers—George Antheil, Marc Blitzstein, Ruth Crawford, Conlon Nancarrow, Roger Sessions, Adolph Weiss, and others (most notably, Aaron Copland, Virgil Thomson, and Roy Harris, who studied with Nadia Boulanger in France)—contributed to American music’s pres- ence on the European continent. As one of the most adventurous com- posers of his generation, Henry Cowell (1897–1965) toured Europe several times before 1933. Traveling to the continent in early June 1923, Cowell played some of his own works in a concert on the ship, and visiting Germany that fall he performed his new piano works in Berlin, Leipzig, and Munich. His compositions, which pioneered the use of chromatic forearm and fist clusters and inside-the-piano (“string piano”) techniques, were “extremely well received and reviewed in Berlin,” a city that, according to the com- poser, “had heard a little more modern music than Leipzig,” where a hos- tile audience started a fistfight on stage.1 A Leipzig critic gave his review a futuristic slant, comparing Cowell’s music to the noisy grind of modern cities; another simply called it noise. Reporting on Cowell’s Berlin concert, Hugo Leichtentritt considered him “the only American representative of musical modernism.” Many writers praised Cowell’s keyboard talents while questioning the music’s quality.2 Such reviews established the tone 8 Beal_Text 12/12/05 5:50 PM Page 9 for the German reception of unconventional American music—usually performed by the composers themselves—that challenged definitions of western art music as well as stylistic conventions and aesthetic boundaries of taste and technique. -

Kurt Lewin and Experimental Psychology in the Interwar Period

'55#466'21 @744)1%71%"#5("#0'5!"#5 2!6243&')2523&'#F4D3&')DG !& ( ) E @7#4)'1 921 11 #4)'1B #4 4 5'"#16"#4 70 2)"6E 1'9#45'6 6@7#4)'1C 42$D4D 1E #1"4'() #46@ #4#(1"#4 &')2523&'5!(7)6 6 C 42$D'!&#)#")#B & 76!&6#4C PD 42$D4D 84%#1#11 QD 42$D4D'6!&#))D 5& #46#'"'%60SD'QIPR Forward I would like to express my gratitude to Professor Dr. Jürgen Renn, Director of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, who supported my pre-doctoral research from the early ideation, through all of its ups and downs until the final line of the disputatio at the Humboldt University of Berlin. Beyond that, the Institute enabled my research project by granting me a PhD scholarship and providing a fruitful work environment, while the well-organized MPIWG library offered me the opportunity to assemble the majority of the material for this book. I am obliged to Professor Dr. Mitchell Ash for his commentaries and insights from his vast knowledge in the history of psychology, as well as for being part of my PhD committee de- spite the geographical distance. I would like to also thank Dr. Alexandre Métraux for advising me on questions related to Lewin’s philosophy of science. Moreover, I am highly indebted to Dr. Massimilano Badino for his scholarly advice, but even more so for his friendship and moral support whenever I needed it. In addition to that, he en- couraged and prepared me to present my work in a variety of international conferences. -

Appendix V; Revised 2/28/06

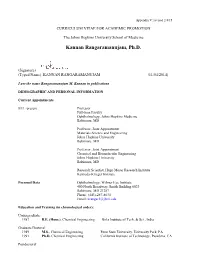

Appendix V; revised 2/4/15 CURRICULUM VITAE FOR ACADEMIC PROMOTION The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Kannan Rangaramanujam, Ph.D. (Signature) (Typed Name) KANNAN RANGARAMANUJAM (11/04/2014) I use the name Rangaramanujam M. Kannan in publications DEMOGRAPHIC AND PERSONAL INFORMATION Current Appointments 8/11 -present Professor Full-time Faculty Ophthalmology, Johns Hopkins Medicine Baltimore, MD Professor, Joint Appointment Materials Science and Engineering Johns Hopkins University Baltimore, MD Professor, Joint Appointment Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering Johns Hopkins University Baltimore, MD Research Scientist, Hugo Moser Research Institute Kennedy-Krieger Institute Personal Data Ophthalmology, Wilmer Eye Institute 400 North Broadway, Smith Building 6023 Baltimore, MD 21287 Phone: (443)-287-8634 Email: [email protected] Education and Training (in chronological order): Undergraduate: 1987 B.E. (Hons.), Chemical Engineering Birla Institute of Tech. & Sci., India Graduate/Doctoral: 1989 M.S., Chemical Engineering Penn State University, University Park, PA 1991 Ph.D. Chemical Engineering California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA Postdoctoral: 8/94 – 7/95 Fellow Chemistry/Chem. Engg. University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN Professional Experience (in chronological order, earliest first) 8/95 - 7/97 Senior Research Engineer, 3M Corporate Research, St. Paul, MN 8/97 - 5/03 Assistant Professor, Chemical Engineering, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI 5/02 - 7/11 Assistant Professor, Biomedical Engineering, Wayne -

City Research Online

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by City Research Online City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Lee, D. ORCID: 0000-0002-5768-9262 (2019). Hornbostel-Sachs Classification of Musical Instruments. Knowledge Organization, 47(1), pp. 72-91. This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/22554/ Link to published version: Copyright and reuse: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] Hornbostel-Sachs Classification of Musical Instruments Abstract This paper discusses the Hornbostel-Sachs Classification of Musical Instruments. This classification system was originally designed for musical instruments and books about instruments, and was first published in German in 1914. Hornbostel-Sachs has dominated organological discourse and practice since its creation, and this article analyses the scheme’s context, background, versions and impact. The position of Hornbostel-Sachs in the history and development of instrument classification is explored. This is followed by a detailed analysis of the mechanics of the scheme, including its decimal notation, the influential broad categories of the scheme, its warrant, and its typographical layout. The version history of the scheme is outlined and the relationships between versions is visualised, including its translations, the introduction of the electrophones category, and the Musical Instruments Museums Online (MIMO) version designed for a digital environment. -

Robert Lehman Papers

Robert Lehman papers Finding aid prepared by Larry Weimer The Robert Lehman Collection Archival Project was generously funded by the Robert Lehman Foundation, Inc. This finding aid was generated using Archivists' Toolkit on September 24, 2014 Robert Lehman Collection The Metropolitan Museum of Art 1000 Fifth Avenue New York, NY, 10028 [email protected] Robert Lehman papers Table of Contents Summary Information .......................................................................................................3 Biographical/Historical note................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents note...................................................................................................34 Arrangement note.............................................................................................................. 36 Administrative Information ............................................................................................ 37 Related Materials ............................................................................................................ 39 Controlled Access Headings............................................................................................. 41 Bibliography...................................................................................................................... 40 Collection Inventory..........................................................................................................43 Series I. General -

Econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Weiss, Frank Dietmar; Heitger, Bernhard; Jüttemeier, Karl-Heinz; Kirkpatrick, Grant; Klepper, Gernot Book — Digitized Version Trade policy in West Germany Kieler Studien, No. 217 Provided in Cooperation with: Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW) Suggested Citation: Weiss, Frank Dietmar; Heitger, Bernhard; Jüttemeier, Karl-Heinz; Kirkpatrick, Grant; Klepper, Gernot (1988) : Trade policy in West Germany, Kieler Studien, No. 217, ISBN 3163454275, Mohr, Tübingen This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/374 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Kieler Studien Institut fiir Weltwirtschaft an der Universitat Kiel Herausgegeben von Herbert Giersch 217 Frank D.Weiss et al. -

This Is a Title

Computational Music Archiving as Physical Culture Theory Prof. Dr. Rolf Bader Institute of Systematic Musicology University of Hamburg Neue Rabenstr. 13, 20354 Hamburg, Germany [email protected] ABSTRACT: The framework of the Computational Music and Sound Archive (COMSAR) is discussed. The aim is to analyze and sort musical pieces of music from all over the world with computational tools. Its analysis is based on Music Information Retrieval (MIR) tools, the sorting algorithms used are Hidden- Markov models and self-organazing Kohonen maps (SOM). Different kinds of systematizations like taxonomies, self-organazing systems as well as bottom-up methods with physiological motivation are discussed, next to the basic signal- processing algorithms. Further implementations include musical instrument ge- ometries with their radiation characteristics as measured by microphone arrays, as well as the vibrational reconstruction of these instruments using physical model- ing. Practically the aim is a search engine for music which is based on musical pa- rameters like pitch, rhythm, tonality, form or timbre using methods close to neu- ronal and physiological mechanisms. Still the concept also suggests a culture the- ory based on physical mechanisms and parameters, and therefore omits specula- tion and theoretical overload. instruments54 as a detailed basis for such a 2 BACKGROUND classification. This classification system still 2.1 KINDS OF MUSIC SYSTEMS holds today and is only enlarged by electronic The aim of Systematic Musicology, right from musical instruments, whos development started the start around 1900, is the seek for universals in the second half of the 19th and was very prominent in the second half of the 20th in music, for rules, relations, systems or 51 interactions holding for all musical styles of all century . -

Wir Werden Wieder Wer 1945–1960

WIR WERDEN WIEDER WER, WESTZONEN UND BUNDESREPUBLIK, 1945–1960 BESATZUNGSHERRSCHAFT UND NACHKRIEGSNOT IV. WIR WERDEN WIEDER WER WESTZONEN UND BUNDESREPUBLIK 1945–1960 Besatzungsherrschaft und Nachkriegsnot Bei Kriegsende herrschte in Deutschland ein auch die individuellen Lebenshoffnungen und schier unbeschreibliches Chaos. Die Zentren die kollektive Moral der Deutschen. der Großstädte waren Trümmerwüsten. Die Über die Organisation ihrer Besatzungsherr- Menschen hausten in Kellern und Notunter- schaft hatten sich die Alliierten bereits 1943 auf künften, der Verkehr stand still. Die Lebens- der Konferenz von Teheran und im Frühjahr Vom 17. Juli bis zum 2. August 1945 tag- sches Verhandlungsziel war die Sicherheit vor Winston Churchill, Harry Truman und Josef Stalin mittel wurden knapp. Die Ordnungsmächte 1945 auf der Konferenz von Jalta geeinigt. Am te in Potsdam eine letzte Gipfelkonferenz der Deutschland, das zweite Ziel lautete: Repara- (v. l. n. r.) auf der Potsda- von gestern, Partei, Staat und Wehrmacht, 5. Juni 1945 gaben die Oberbefehlshaber der »Großen Drei«. Delegationsleiter waren der tionen von Deutschland. Mit der Übergabe mer Konferenz 1945 waren von der Bildfläche verschwunden. Für vier Siegermächte in Berlin mit drei Proklama- neue amerikanische Präsident Truman (1945– der deutschen Gebiete östlich der Oder-Neiße- Millionen von KZ-Häftlingen, Zwangsver- tionen den Beginn der Besatzungsherrschaft 1953), der sowjetische Generalissimus J. W. Linie an die prosowjetisch ausgerichtete polni- schleppten und ausländischen Kriegsgefan- über Deutschland förmlich und völkerrechtlich Stalin (Parteichef von Ende der Zwanziger- sche Regierung und der Ausweisung der dor- genen hatte mit dem Kriegsende die Stunde verbindlich bekannt: Sie erklärten die Über- jahre bis 1953) und der britische Premiermi- tigen deutschen Bevölkerung hatte die Sowje- der Befreiung geschlagen. -

Linked Adrenoleukodystrophy: Pathology, Pathophysiology, Diagnostic Testing, Newborn Screening and Therapies

Received: 21 May 2019 | Accepted: 21 November 2019 DOI: 10.1002/jdn.10003 RESEARCH ARTICLE X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy: Pathology, pathophysiology, diagnostic testing, newborn screening and therapies Bela R. Turk1 | Christiane Theda2 | Ali Fatemi1 | Ann B. Moser1 1Hugo W Moser Research Institute, Kennedy Krieger Institute, Baltimore, MD, USA 2Neonatal Services, Royal Women's Hospital, Murdoch Children's Research Institute and University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia Correspondence Ann B. Moser, Hugo W Moser Research Abstract Institute, Kennedy Krieger Institute, 707 N. Adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD) is a rare X-linked disease caused by a mutation of Broadway, Baltimore, MD, USA. the peroxisomal ABCD1 gene. This review summarizes our current understanding Email: [email protected] of the pathogenic cell- and tissue-specific roles of lipid species in the context of Funding information experimental therapeutic strategies and provides an overview of critical historical Equipment and partial salary support for AM and AF was provided by the developments, therapeutic trials and the advent of newborn screening in the USA. In Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities ALD, very long-chain fatty acid (VLCFA) chain length-dependent dysregulation of Research Centers at the Kennedy endoplasmic reticulum stress and mitochondrial radical generating systems inducing Krieger Institute and Johns Hopkins University, Grant/Award Number: NICHD cell death pathways has been shown, providing the rationale for therapeutic moiety- U54HD079123 specific