Palaeo-Philosophy: Archaic Ideas About Space and Time

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buy Generic Viagra

TTHHOUGHTTSS OOFF EETTHHEERRNNAALL WIISSDOOMM Chosen Thoughts of spiritual Teachers of the UNIVERSAL BROTHERHOOD OF LIGHT EEnnccyyccllooppeeddiiaa for QQuueessttiioonnss ccoonncceerrnniinngg DDaaiillyy LLiiffee eeBBooookk 11-- 1111 Understand Life and myself anew: clear Answers to Questions concerning Daily Life www.realpeacework-akademie.info/jena UN D E RS T A N D L IIFE A N D M Y S E L F A N E W : C L E A R A N S W E R S T O Q U E S T I O N S C O N C E R N I N G D A I L Y L I F E b PPuubblliisshheerr Loovvee(+)Wissddoomm(=)TTrruutthh UN D E R S T A N D L IIFE A N D M Y S E L F A N E W : C L E A R A N S W E R S T O Q U E S T I O N S C O N C E R N I N G D A I L Y L I F E eBook 01: Means to bring ‘on ’ Prenatal Education & Spiritual Electroplating eBook 02: A new Light on Prayer eBook 03: The Importance of having an High Ideal eBook 04: Master & Discipleship eBook 05: The Kingdom of God & His Righteousness eBook 06: The Two Principles – Masculine and Feminine eBook 07: Angels & the Tree of Life eBook 08: The Sublime Origin and Goal of Sexuality and the Sexual Force eBook 09: The hidden capacity of Human beings eBook 10: Being Member of a Family …and its different Connections with the world eBook 11: The Reasons behind Suffering eBook 12: The Cosmic meaning of Marriage eBook 42: Why we should accept Reincarnation eBook 13: Holidays eBook 43: A Servant of God eBook 14: Music and Creation eBook 44: Becoming a Spiritual Disciple eBook 15: The Quintessence of Christianity eBook 45: How to work for Peace in the World eBook 16: Purity as the -

Yalin Akcevin the Etruscans Space in Etruscan Sacred Architecture And

Yalin Akcevin The Etruscans Space in Etruscan Sacred Architecture and Its Implications on Use Abstract Space is no doubt an important subject for the Etruscan religion, whether in the inauguration of cities and sacred areas, or in the divination of omens through the Piacenza liver in divided spaces of a sacrificial liver. It is then understandable that in the architecture and layout of the temples and sacred places, the usage of space, bears specific meaning and importance to the use and sanctity of the temple. Exploring the relationship between architectural spaces, and religious and secular use of temple complexes can expand the role of the temple from simply the ritualistic. It can also be shown that temples were both monuments to gods and Etruscans, and that these places were living spaces reflecting the Etruscan sense of spatial relations and importance. I. Introduction The Etruscans, in their own rights, were people whose religion was omnipresent in their daily lives. From deciding upon the fate of battle to the inauguration of cities and sacred spaces, the Etruscans held a sense of religion close to themselves. The most prominent part of this religion however, given what is left from the Etruscans, is the emphasis on the use of space. The division and demarcation of physical space is seen in the orthogonal city plan of Marzabotto with cippus placed at prominent crossroads marking the cardinal directions, to the sixteen parts of the heaven and the sky on the Piacenza liver. Space had been used to divine from lighting, conduct augury from the flight of birds and haruspicy from the liver of sacrificial animals. -

Cosmos: a Spacetime Odyssey (2014) Episode Scripts Based On

Cosmos: A SpaceTime Odyssey (2014) Episode Scripts Based on Cosmos: A Personal Voyage by Carl Sagan, Ann Druyan & Steven Soter Directed by Brannon Braga, Bill Pope & Ann Druyan Presented by Neil deGrasse Tyson Composer(s) Alan Silvestri Country of origin United States Original language(s) English No. of episodes 13 (List of episodes) 1 - Standing Up in the Milky Way 2 - Some of the Things That Molecules Do 3 - When Knowledge Conquered Fear 4 - A Sky Full of Ghosts 5 - Hiding In The Light 6 - Deeper, Deeper, Deeper Still 7 - The Clean Room 8 - Sisters of the Sun 9 - The Lost Worlds of Planet Earth 10 - The Electric Boy 11 - The Immortals 12 - The World Set Free 13 - Unafraid Of The Dark 1 - Standing Up in the Milky Way The cosmos is all there is, or ever was, or ever will be. Come with me. A generation ago, the astronomer Carl Sagan stood here and launched hundreds of millions of us on a great adventure: the exploration of the universe revealed by science. It's time to get going again. We're about to begin a journey that will take us from the infinitesimal to the infinite, from the dawn of time to the distant future. We'll explore galaxies and suns and worlds, surf the gravity waves of space-time, encounter beings that live in fire and ice, explore the planets of stars that never die, discover atoms as massive as suns and universes smaller than atoms. Cosmos is also a story about us. It's the saga of how wandering bands of hunters and gatherers found their way to the stars, one adventure with many heroes. -

Transmission of Liver Divination from East to West

THE TRANSMISSION OF LIVER DMNATION FROM EAST TO WEST by MARy R. BACHVAROVA "The spread of hepatoscopy is one of the clearest examples of cultural contact in the orien talizing period. It must have been a case of East-West understanding on a relatively high, technical level. The mobility of migrant charismatics is the natural prerequisite for this diffusion, the international role of soughl-afler specialists, who were, as far as their art was concerned, nevertheless bound to their father-teachers. We cannot expect to find many archaeologically identifiable traces of such people, other than some excep tional instances."1 1. Introduction Walter Burkert's theory of freely moving craftsmen of verbal art and ritual tech nology bringing stories and magico-religious practices to the west in the orientaliz ing period (750-650 BCE) has caught the imagination of Classical scholars and been given great explanatory power in subsequent discussions of textual and cul turallinks across the Mediterranean. By simply referring to the theory as a given, Classical scholars have been able to avoid the questions of why and how, and to move directly to a discussion of the motifs or practices under consideration, using the Near Eastern sources to analyze Greek cultural artifacts. A re-examination of Burkert's theory as a whole and his interpretation of its component parts is certain lyoverdue. Key to Burkert's argument concerning the role of itinerant diviners transmit ting cultural features is the shared practice of liver divination. He argues, first, that parallels in the terminology of Greek and Akkadian hepatoscopy are evidence that the Greek hepatoscopic tradition was influenced directly by the Mesopotamian practice; secondly, he sees the bronze liver model found at Piacenza in Italy as directly related to the second-millennium Near Eastern liver models (he does not discuss the uninscribed terra cotta liver from Falerii Veteres); and finally, he argues that "migrant charismatics" brought the practice to the west. -

Hammond2009.Pdf (13.01Mb)

Postgraduate Programmes in the SCHOOL of HISTORY, CLASSICS and ARCHAEOLOGY The Iconography of the Etruscan Haruspex Supervisor: Name: Sarah Hammond Dr Robert Leighton 2009 SCHOOL of HISTORY, CLASSICS and ARCHAEOLOGY DECLARATION OF OWN WORK This dissertation has been composed by Sarah Hammond a candidate of the MSc Programme in MScR, Archaeology, run by the School of History, Classics and Archaeology at the University of Edinburgh. The work it represents is my own, unless otherwise explicitly cited and credited in appropriate academic convention. I confirm that all this work is my own except where indicated, and that I have: Clearly referenced/listed all sources as appropriate Referenced and put in inverted commas all quoted text of more than three words (from books, web, etc) Given the sources of all pictures, data etc. that are not my own Not made any use of the essay(s) of any other student(s) either past or present Not sought or used the help of any external professional agencies for the work Acknowledged in appropriate places any help that I have received from others (e.g. fellow students, technicians, statisticians, external sources) Complied with any other plagiarism criteria specified in the Course handbook I understand that any false claim for this work will be penalised in accordance with the University regulations Signature: Name (Please PRINT): SARAH HAMMOND Date: 22/06/2009 The Iconography of the Etruscan Haruspex by Sarah Naomi Hammond MSc by Research, Archaeology The University of Edinburgh 2009 Word count: 25,000 Abstract The religious rituals of the Etruscans incorporated several forms of divination including the practices of extispicy and hepatoscopy, the arts of divining through the examination of sacrificed animal entrails, and specifically the liver. -

Luce in Contesto. Rappresentazioni, Produzioni E Usi Della Luce Nello Spazio Antico / Light in Context

Light in Antiquity: Etruria and Greece in Comparison Laura Ambrosini Abstract This study discusses lighting devices in Etruria and the comparison with similar tools in Greece, focusing on social and cultural differences. Greeks did not use candlestick- holders; objects that have been improperly identified ascandelabra should more properly be classified as lamp/utensil stands. The Etruscans, on the other hand, preferred to use torchlight for illumination, and as a result, the candelabrum—an upright stand specifically designed to support candles — was developed in order to avoid burns to the hands, prevent fires or problems with smoke, and collect ash or melting substances. Otherwise they also used utensil stands similar to the Greek lamp holders, which were placed near the kylikeion at banquets. Kottaboi in Etruria were important utensils used in the context of banquets and symposia, while in Greece, they were interchangeable with lamp/utensil stands. Introduction Light in Etruria1 certainly had a great importance, as confirmed by the numerous gods connected with light in its various forms (the thunderbolt, the sun, the moon, the dawn, etc.).2 All the religious doctrines and practices concerning the thunderbolt, the light par excellence, are relevant in this concern. Tinia, the most important god of the Etruscan pantheon (the Greek Zeus), is often depicted with a thunderbolt. Sometimes also Menerva (the Greek Athena) uses the thunderbolt as weapon (fig. 1), which does not seem to be attested in Greece.3 Thesan was the Etruscan Goddess of the dawn identified with the Greek Eos; Cavtha is the name of the Etruscan god of the sun in the cult, while Usil is the sun as an appellative or mythological personality. -

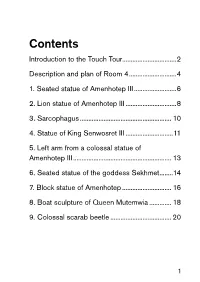

Contents Introduction to the Touch Tour

Contents Introduction to the Touch Tour................................2 Description and plan of Room 4 ............................4 1. Seated statue of Amenhotep III .........................6 2. Lion statue of Amenhotep III ..............................8 3. Sarcophagus ...................................................... 10 4. Statue of King Senwosret III ............................11 5. Left arm from a colossal statue of Amenhotep III .......................................................... 13 6. Seated statue of the goddess Sekhmet ........14 7. Block statue of Amenhotep ............................. 16 8. Boat sculpture of Queen Mutemwia ............. 18 9. Colossal scarab beetle .................................... 20 1 Introduction to the Touch Tour This tour of the Egyptian Sculpture Gallery is a specially designed Touch Tour for visitors with sight difficulties. This guide gives you information about nine highlight objects in Room 4 that you are able to explore by touch. The Touch Tour is also available to download as an audio guide from the Museum’s website: britishmuseum.org/egyptiantouchtour If you require assistance, please ask the staff on the Information Desk in the Great Court to accompany you to the start of the tour. The sculptures are arranged broadly chronologically, and if you follow the tour sequentially, you will work your way gradually from one end of the gallery to the other moving through time. Each sculpture on your tour has a Touch Tour symbol beside it and a number. 2 Some of the sculptures are very large so it may be possible only to feel part of them and/or you may have to move around the sculpture to feel more of it. If you have any questions or problems, do not hesitate to ask a member of staff. -

Biblical Cosmology: the Implications for Bible Translation

Journal of Translation, Volume 9, Number 2 (2013) 1 Biblical Cosmology: The Implications for Bible Translation John R. Roberts John Roberts is a Senior Linguistics Consultant with SIL International. He has a Ph.D. in Linguistics from University College London. From 1978 to 1998 John supervised the Amele language project in Papua New Guinea during which time translations of Genesis and the New Testament were completed. John has taught graduate level linguistics courses in the UK, USA, Sweden, S. Korea and W. Asia. He has published many articles in the domains of descriptive linguistics and Bible translation and several linguistics books. His current research interest is to understand Genesis 1–11 in an ancient Near East context. Abstract We show that the creation account in Genesis 1.1–2.3 refers to a worldview of the cosmos as the ancient Mesopotamians and ancient Egyptians understood it to be. These civilisations left behind documents, maps and iconography which describe the cosmological beliefs they had. The differences between the biblical cosmology and ancient Near East cosmologies are observed to be mainly theological in nature rather than cosmological. However, the biblical cosmology is conceptually different to a modern view of the cosmos in significant ways. We examine how a range of terms are translated in English Bible translations, including ḥōšeḵ, təhôm, rāqîᵃʿ, hammayim ʾăšer mēʿal lārāqîᵃʿ, and mayim mittaḥaṯ lā’āreṣ, and show that if the denotation of these terms is in accordance with a modern worldview then this results in a text that has incongruities and is incoherent in the nature of the cosmos it depicts. -

1 Name 2 Zeus in Myth

Zeus For other uses, see Zeus (disambiguation). Zeus (English pronunciation: /ˈzjuːs/[3] ZEWS); Ancient Greek Ζεύς Zeús, pronounced [zdeǔ̯s] in Classical Attic; Modern Greek: Δίας Días pronounced [ˈði.as]) is the god of sky and thunder and the ruler of the Olympians of Mount Olympus. The name Zeus is cognate with the first element of Roman Jupiter, and Zeus and Jupiter became closely identified with each other. Zeus is the child of Cronus and Rhea, and the youngest of his siblings. In most traditions he is married to Hera, although, at the oracle of Dodona, his consort The Chariot of Zeus, from an 1879 Stories from the Greek is Dione: according to the Iliad, he is the father of Tragedians by Alfred Church. Aphrodite by Dione.[4] He is known for his erotic es- capades. These resulted in many godly and heroic offspring, including Athena, Apollo, Artemis, Hermes, the Proto-Indo-European god of the daytime sky, also [10][11] Persephone (by Demeter), Dionysus, Perseus, Heracles, called *Dyeus ph2tēr (“Sky Father”). The god is Helen of Troy, Minos, and the Muses (by Mnemosyne); known under this name in the Rigveda (Vedic San- by Hera, he is usually said to have fathered Ares, Hebe skrit Dyaus/Dyaus Pita), Latin (compare Jupiter, from and Hephaestus.[5] Iuppiter, deriving from the Proto-Indo-European voca- [12] tive *dyeu-ph2tēr), deriving from the root *dyeu- As Walter Burkert points out in his book, Greek Religion, (“to shine”, and in its many derivatives, “sky, heaven, “Even the gods who are not his natural children address [10] [6] god”). -

Nature Is a Heraclitean Fire"

' • Studies in the Spirituality of Jesuits JAN 14199? "Nature Is a Heracliteari Fire" Reflections on Cosmology in an Ecological Age LIBRARY 'BK David S. Toolan, S.J. 23/5 November 1991 \J Pot t t->, THE SEMINAR ON JESUIT SPIRITUALITY A group of Jesuits appointed from their provinces in the United States. The Seminar studies topics pertaining to the spiritual doctrine and practice of Jesuits, especially American Jesuits, and communicates the results to the members of the provinces. This is done in the spirit of Vatican IPs recommendation to religious institutes to recapture the original in- spiration of their founders and to adapt it to the circumstances of modern times. The Seminar welcomes reactions or comments in regard to the material which it publishes. The Seminar focuses its direct attention on the life and work of the Jesuits of the United States. The issues treated may be common also to Jesuits of other regions, to other priests, religious, and laity, to both men and women. Hence the Studies, while meant especially for American Jesuits, are not exclusively for them. Others who may find them helpful are cordially welcome to read them. CURRENT MEMBERS OF THE SEMINAR John F. Baldovin, S.J., teaches both historical theology and liturgical theology at the Jesuit School of Theology at Berkeley, CA (1991). John B. Breslin, S.J., directs the Georgetown University Press and teaches English at Georgetown University in Washington, DC (1990). Michael L. Cook, S.J., teaches systematic theology at Gonzaga University in Spokane, WA (1991). Brian E. Daley, S.J., teaches hisorical theology at the Weston School of Theology in Cambridge, MA (1991). -

Eco-Theology: Aiga – the Household of Life

ECO-THEOLOGY: AIGA – THE HOUSEHOLD OF LIFE A PERSPECTIVE FROM LIVING MYTHS AND TRADITIONS OF SAMOA Ama’amalele Tofaeono ECO-THEOLOGY: AIGA – THE HOUSEHOLD OF LIFE A PERSPECTIVE FROM LIVING MYTHS AND TRADITIONS OF SAMOA World Mission Script 7 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or stored in a retrieval system, or trans- mitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the Erlanger Verlag für Mission und Ökumene. Die Deutsche Bibliothek – CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Tofaeono, Ama’amalele: Eco-theology: Aiga – the household of life : a perspective from living myths and traditions of Samoa / by Ama’amalele Tofaeono. – Erlangen : Erlanger Verl. für Mission und Ökumene, 2000 (World Mission Script ; 7) Zugl.: Neuendettelsau, Augustana-Hochsch., Diss., 2000 ISBN 3-87214-327-1 © 2000 Erlanger Verlag für Mission und Ökumene, Erlangen Layout: Andreas-Martin Selignow – www.selignow.de Printed by Freimund-Druckerei, Neuendettelsau CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................ 11 0. GENERAL INTRODUCTION ......................................................................... 13 0.1. Identification and Exposition of the Eco-Theological Problem ....................... 13 0.2. A Jewish Perspective .............................................................................................. 15 0.3. Thesis Statements ................................................................................................... -

Etruscan News 20

Volume 20 20th ANNIVERSARY ISSUE Winter 2018 XXIX Conference of Etruscan and of Giacomo Devoto and Luisa Banti, Italic Studies and where he eventually became Luisa L’Etruria delle necropoli Banti’s successor as Professor of Etruscan Studies at the University of rupestri Florence. Tuscania-Viterbo For twenty years he was the October 26-28, 2017 President of the National Institute of Reviewed by Sara Costantini Etruscan and Italic Studies, with me at his side as Vice President, and for ten From 26 to 28 October, the XXIX years he was head of the historic Conference of Etruscan and Italic Etruscan Academy of Cortona as its Studies, entitled “The Etruria of the Lucumo. He had long directed, along- Rock-Cut Tombs,” took place in side Massimo Pallottino, the Course of Tuscania and Viterbo. The many schol- Etruscology and Italic Antiquities of the ars who attended the meeting were able University for Foreigners of Perugia, to take stock of the new knowledge and and was for some years President of the the problems that have arisen, 45 years Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae after the first conference dedicated to Classicae (LIMC), for which he wrote interior Etruria. The first day’s activi- more than twenty entries. ties, which took place in the Rivellino Cortona, member of the Accademia dei Giovannangelo His activity as field archaeologist Theater “Veriano Luchetti” of Tuscania, Lincei and President of the National Camporeale included the uninterrupted direction, with excellent acoustics, had as their Institute of Etruscan and Italic Studies; 1933-2017 since 1980, of the excavation of the main theme the historical and archaeo- he died on July 1 of this year.