The Morning After a Night to Remember: the Lesson of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ghosts of the Abyss. Titanic’S Bow As Seen from Mir II

A Dive to the titAnic Only a handful of craft can transport people to the deepest ocean realms, and I, as a maritime archaeologist, have been fortunate enough to dive in several of these deep submergence vehicles, also known as submersibles. My most exciting dive was to the wreck of the Titanic, which lies two and a half miles beneath the surface. The grand ocean liner sank in the early morning of April 15, 1912, after striking an iceberg, with a loss of more than 1,500 lives. In the fall of 2001, I was invited to take part in a Titanic expedition headed by James Cameron, director of the 1997 film Titanic. The goal of the expedition was to film the vessel’s remains using deep submersibles on which were mounted powerful lights and a unique high-definition 3D video camera. Cameron then produced a 3D IMAX documentary film, Ghosts of the Abyss. Titanic’s bow as seen from Mir II 8 dig www.digonsite.com Dig1105_Deep_DrDigRedo.indd 8 3/16/11 10:52 AM A Dive To The TiTAbynic John D. Broadwater t’s early morning on September 10, 2001, and I am aboard the 122-foot-long Russian research vessel Akademik Mstislav Keldysh. It is equipped with two submersibles, I Mir I and Mir II, both capable of descending 20,000 feet. The Mirs are 26 feet long, weigh more than 18 tons, and can carry three people—a pilot and two scientists or observers. I am participating in this expedition as a representative of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). -

Download Issue

WILSON QUARTERLY SPRING I979 WOODROW WILSON INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR SCHOLARS Smitlisonian Institution Bt~tidi~tgWashington D.C. WOODROW WILSON INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR SCHOLARS Director, James H. Billington Deputy Director, George R. Packard THE WILSON QUARTERLY Editor: Peter Braestrup Managing Editor: Anna Marie Torres Associate Editor (Periodicals): Philip S. Cook Associate Editor (Essays): Cullen Murphy Associate Editor (Books): Lois Decker O'Neill Contributing Editors: Nicholas Burke, Michael Glennon, Suzanne deLesseps, Gustav Magrinat, Martin Miszerak, Joseph S. Murchison, Stuart Rohrer, Raphael Sagalyn, Carol Simons Copy Editor: Bradley B. Rymph Production Assistant: Nancy B. Joyner Administrative Assistant: James Gregory Sherr Production Typists: Jacqueline Levine, Frances Tompkins Research Assistants: David L. Aasen, Bruce Carlson, Don L. Ford, Matthew Kiene, Karen M. Kopf, Mary McNeil, Finn Murphy, James J. O'Hara, Dena J. Pearson Librarian: Zdenek David Art Director: Elizabeth Dixon Business Manager: William M. Dunn Circulation Coordinator: William H. Mello Editorial Advisers: Prosser Gifford, Abraham Lowenthal, Richard Seamon, S. Frederick Starr Published in Jamiarv, April, July, and October by the Woodrow Wilson Interna- tional Center for Scholars, Smithsonian Institution Building, Washington, D.C. 20560. Copyright @ 1979 by the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. THE WILSON QUARTERLY is a registered trademark. Subscriptions: oneyear, $12; two vears, $21; three years, $30. Foreign subscriptions: oneyear, $14; two ?ears, $25; three years, $36. Foreign subscriptions ainnail: one year, $24; two vears, $45; three years, $66. Lifetime subscription (domestic only): $150. Single copies and back issues mailed u on request: $4; outside U.S. and possessions, $6.50. Second-class postage paidat Washington, D.C., and additional mailing offices. -

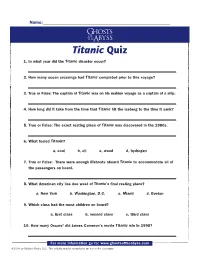

Ghosts of the Abyss: Titanic Quiz

Name:_______________________________________________________________ Titanic Quiz 1. In what year did the Titanic disaster occur? 2. How many ocean crossings had Titanic completed prior to this voyage? 3. True or False: The captain of Titanic was on his maiden voyage as a captain of a ship. 4. How long did it take from the time that Titanic hit the iceberg to the time it sank? 5. True or False: The exact resting place of Titanic was discovered in the 1980s. 6. What fueled Titanic? a. coal b. oil c. wood d. hydrogen 7. True or False: There were enough lifeboats aboard Titanic to accommodate all of the passengers on board. 8. What American city lies due west of Titanic’s final resting place? a. New York b. Washington, D.C. c. Miami d. Boston 9. Which class had the most children on board? a. first class b. second class c. third class 10. How many Oscars® did James Cameron’s movie Titanic win in 1998? For more information go to: www.ghostsoftheabyss.com ©2004 by Walden Media, LLC. This activity may be reproduced for use in the classroom. Titanic Quiz Answers 1. In what year did the Titanic disaster occur? 1912 2. How many ocean crossings had Titanic completed prior to this voyage? None: Titanic was on her maiden voyage. 3. True or False: The captain of Titanic was on his maiden voyage as a captain of a ship. False. After 38 years of service to the White Star Line, it was to be Captain Edward Smith’s final voyage. 4. How long did it take from the time that Titanic hit the iceberg to the time it sank? Titanic struck the iceberg at 11:40 PM on April 15 and sank approximately 2 hours and forty minutes later, at 2:20 AM on April 16. -

Title Sub-Title Author

Title Sub-Title Author Call #1 Call #2 Call #3 "A" Is For Alibi A Kinsey Millhone Mystery Grafton, Sue FMY GRA "B" Is For Burglar Grafton, Sue FMY GRA "C" Is For Corpse A Kinsey Millhone Mystery Grafton, Sue FMY GRA "D" Is For Deadbeat A Kinsey Millhone Mystery Grafton, Sue FMY GRA "E" Is For Evidence A Kinsey Millhone Mystery Grafton, Sue FMY GRA "F" Is For Fugitive Grafton, Sue FMY GRA "G" Is For Gumshoe A Kinsey Millhone Mystery Grafton, Sue FMY GRA "H" Is For Homicide Grafton, Sue FMY GRA "I" Is For Innocent Grafton, Sue FMY GRA "J" Is For Judgement Grafton, Sue FMY GRA "K" Is For Killer Grafton, Sue FMY GRA "L" Is For Lawless Grafton, Sue FMY GRA "M" Is For Malice Grafton, Sue FMY GRA "N" Is For Noose Grafton, Sue FMY GRA "O" Is For Outlaw Grafton, Sue FMY GRA "S" Is For Silence Grafton, Sue F GRA 10-lb Penalty Francis, Dick F FRA 10 Best Questions For Living With Alzheimer's, The The Script You Need To Take Control Of Bonner,Your Health Dede 616 .831 Bon 10 Best Things About My Dad, The Loomis, Christine E/F Loo 10 Drowsy Dinosaurs Auger, Wendy Frood E/F AUG 10 Fat Turkeys Johnston, Tony E/F Joh 10 For Dinner Bogart, Jo Ellen E/F BOG 10 Little Rubber Ducks Carle, Eric E/F Car 10 Trick-or-treaters A Halloween Counting Book Schulman, Janet [E] Sch 10% Happier How I Tamed The Voice In My Head, ReducedHarris, Stress Dan Without Losing158 My Edge,.1 And FoundHAR Self-Help That Actually Works : A True Story 10,000 Dreams Interpreted What's in a Dream Miller, Gustavus Hindman 135 3 MIL 10:04 Lerner, Ben F LER 100 Amazing Magic Tricks Good, Arthur I/793 .8 GOO 100 Colorful Granny Squares To Crochet [dozens Of Mix And Match Combos AndMorgan, Fabulous Leonie Projects] 746 .432 MOR 100 Hikers 100 Hikes From Tobermory to Kilimanjaro Camani, Andrew 796 51 CAM 100 Mistakes That Changed History Backfires And Blunders That Collapsed Empires,Fawcett, Crashed Bill Economies,909 And AlteredFAW The Course Of Our World 100 Most Important Women Of The 20th Century. -

Exploring the Deep : the Titanic Expeditions Ebook

EXPLORING THE DEEP : THE TITANIC EXPEDITIONS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK James Cameron | 252 pages | 04 Jun 2013 | Insight Editions | 9781608871223 | English | San Rafael, United States Exploring the Deep : The Titanic Expeditions PDF Book Bookmark this article. Farewell, Titanic: Her Final Legacy. Institutional Investor. Lynch, Don New Research. He had been so focused on the task that the achievement of reaching 13, feet only hit him when he regained contact with his crew during the ascent. The first camp has argued that artefacts from around the wreck should be recovered and conserved, while the latter camp argues that the entire wreck site should have been left undisturbed as a mass grave. They are capable of reaching ocean depths of 20, feet 6,m. Analysis by Henrietta Mann and Bhavleen Kaur, both of Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia , in conjunction with other scientists and researchers of the University of Seville in Spain, has determined that the wreck of Titanic will not exist by and that preservation of Titanic is impossible. In late August , the groups vying to purchase the 5, relics included one by museums in England and Northern Ireland, with assistance from James Cameron and some financial support from National Geographic. Visit the Titanic. Navy and operated by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution under charter agreement for the American ocean research community. With the submersible still resting on its metal launching platform, one end of the platform slowly rose from the dock and we slid backward into the sea. This was essentially a drillship with sonar equipment and cameras attached to the end of the drilling pipe. -

6 Large Temple of Abu Simbel, Egypt, Built

Large temple of Abu Simbel, Egypt, built ca. 1264 –1244 BCE, reconstructed 1960 –1968 CE. Photograph of re-inauguration day, September 22, 1968, by Torgny Säve-Söderbergh. 6 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/GREY_a_00094 by guest on 01 October 2021 Integrities: The Salvage of Abu Simbel LUCIA ALLAIS In 1965, British architectural historian and technologY enthusiast ReYner Banham Wrote a letter to a preserVationist Who had asked him to interVene against the demolition of the Reliance Building in Chicago. “The daY You find me speaking up for the preserVation of anY building WhatsoeVer,” Banham Wrote, “send floWers, the neXt stage Will be the general paralYsis of the insane.” Banham refused to engage in What he called “idiotic preserVationist panics” for fear of being subjected to similar requests from “eVerY crackpot period group and broken-doWn countrY-house oWner in England.” 1 But he could also haVe aimed his sarcasm at preserVationists With much more cos - mopolitan tastes. In 1965, after all, Le Corbusier’s Villa SaVoYe Was declared a national historic monument in France, thanks in part to an international adVocacY campaign bY modernist architects and historians, including Siegfried Giedion. 2 The mid-1960s constitutes something of a historical turn - ing point, When a WaVe of ferVor sWept up architects and architectural histo - rians of eVerY allegiance across Europe and North America, and transformed architectural preserVation from a fringe moVement into a mainstream political cause. A feW dates serVe to eVidence this shift. In 1963, architects (including Philip Johnson) joined urban actiVists (including Jane Jacobs) to protest the demolition of NeW York’s Penn Station. -

Hofstra University Film Library Holdings

Hofstra University Film Library Holdings TITLE PUBLICATION INFORMATION NUMBER DATE LANG 1-800-INDIA Mitra Films and Thirteen/WNET New York producer, Anna Cater director, Safina Uberoi. VD-1181 c2006. eng 1 giant leap Palm Pictures. VD-825 2001 und 1 on 1 V-5489 c2002. eng 3 films by Louis Malle Nouvelles Editions de Films written and directed by Louis Malle. VD-1340 2006 fre produced by Argosy Pictures Corporation, a Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer picture [presented by] 3 godfathers John Ford and Merian C. Cooper produced by John Ford and Merian C. Cooper screenplay VD-1348 [2006] eng by Laurence Stallings and Frank S. Nugent directed by John Ford. Lions Gate Films, Inc. producer, Robert Altman writer, Robert Altman director, Robert 3 women VD-1333 [2004] eng Altman. Filmocom Productions with participation of the Russian Federation Ministry of Culture and financial support of the Hubert Balls Fund of the International Filmfestival Rotterdam 4 VD-1704 2006 rus produced by Yelena Yatsura concept and story by Vladimir Sorokin, Ilya Khrzhanovsky screenplay by Vladimir Sorokin directed by Ilya Khrzhanovsky. a film by Kartemquin Educational Films CPB producer/director, Maria Finitzo co- 5 girls V-5767 2001 eng producer/editor, David E. Simpson. / una produzione Cineriz ideato e dirètto da Federico Fellini prodotto da Angelo Rizzoli 8 1/2 soggètto, Federico Fellini, Ennio Flaiano scenegiatura, Federico Fellini, Tullio Pinelli, Ennio V-554 c1987. ita Flaiano, Brunello Rondi. / una produzione Cineriz ideato e dirètto da Federico Fellini prodotto da Angelo Rizzoli 8 1/2 soggètto, Federico Fellini, Ennio Flaiano scenegiatura, Federico Fellini, Tullio Pinelli, Ennio V-554 c1987. -

Themed Topic Booklist on the Titanic by Maryelizabeth Melillo for Grades

1 Ballard, R. D. (1988). Exploring the Titanic. New York: Scholastic. Exploring The Titanic by Robert D. Ballard begins with an account of Dr. Ballard's dream to locate the Titanic. Throughout the book, it provides a detailed description of the history of “the Unsinkable Ship,” its design, the eloquence of its stately rooms, its splendor, and the events of the night the ship sank. In addition to the story of the Titanic, the story of its discovery is unveiled and overshadowed by the hour it was found, which was close to the actual sinking time of this vessel. The pictures of its brilliance and its wreckage provide perspective on the events of the Titanic's magnificent birth followed by a tragic demise. This realistic chronicle of events demonstrates the importance of this find and its history. This book is good for English Language Learners because it provides an account of this ship’s story both historically and visually. The pictures help the student understand today’s discovery of the Titanic and its historical yet tragic existence and maiden voyage. WIDA Proficiency Level: Bridging Reading Level: 6.7 Lexile Measure: 980L DRA: 40 GRL: Q Language: English Available format: paperback and hardcover ISBN paperback: 0-590-41952-8 ISBN hardcover: 0-590-41953-6 Teacher Resources: www.labroda.com/exploring-the-titanic-robert-ballard-lessons.htm http://www.slj.com/search-results/?q=titanic#_ 2 Ballard, R. D., Archbold, R., & Marschall, K. (1998). Ghost liners: Exploring the world's greatest lost ships. Boston: Little, Brown. Ghost Liners Exploring the world's greatest lost ships by Robert D. -

1 Lazuli Bunting Manuscript Review History Manuscript

1 LAZULI BUNTING MANUSCRIPT REVIEW HISTORY MANUSCRIPT (ROUND 1) Abstract One hundred years after its sinking, the Titanic holds many in its thrall. If not quite a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma, it continues to captivate consumers worldwide. This paper explores RMS Titanic from a cultural branding perspective, arguing that “the unfathomable brand” can be fruitfully examined through the ambiguous lens of literary criticism. Although brand ambiguity is often regarded as something to be avoided, this article demonstrates that ambiguity is a multi-faceted construct, five aspects of which are discernible in the brand debris field surrounding the totemic vessel. Combining empirical research and archival investigation, the article contends that ambiguity is a strength, rather than a weakness, of iconic brands like Titanic. This document is part of a JCR Manuscript Review History. It should be used for educational purposes only. 2 In my own dreams of the Titanic, I am a disembodied robotic eye, gliding like a wayward star through the adits of its wrecked Atlantean cathedral, or through a porthole oculus, taking account of tilted apses and saloons, wandering their marble stairs and passageways. —Ciaran Carson, The Star Factory Paul Tillich (1952), the eminent theologian, defines maturity as an ability to tolerate ambiguity. If this is correct, then branding probably qualifies as a mature marketing practice. The early certainties of branding, encapsulated in Rosser Reeves’ (1961) USP, are gradually giving way to cultural and critical perspectives that are more oceanic, more polysemic, more amorphous than before (Bengtsson and Ostberg 2006; Beverland 2009; Kates and Goh 2003; Puntoni, Schroeder, and Ritson 2010). -

Braynards Story: Titanic Postcards Ebook Free Download

BRAYNARDS STORY: TITANIC POSTCARDS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Frank O. Braynard | 6 pages | 28 Mar 2003 | Dover Publications Inc. | 9780486256115 | English | New York, United States Story of the 'TITANIC' in 24 Postcards - Titanic Historical Society, Inc. Whether you are looking for a postcard for kids or adults, we have something for everyone. You can easily search by style, color, and size for the ideal postcard design. Gift Ideas. All 36 Best Sellers Specials 1. Availability In stock at Mighty Ape 8 Available from supplier Secret Garden: 20 Postcards Johanna Basford. In stock - ships today. Due Nov 3rd. Magnum Photos: Postcards. Pantone Postcards Postcard Box. Available - Usually ships in days. Star Wars Frames: Postcards. Agrandir les images. Vendeur AbeBooks depuis 29 mai Evaluation du vendeur. Poser une question au libraire. Titre : Story of the "Titanic" Postcards : Etat du livre : Comme neuf. Items may be returned only if the item is not accurately described. About this Item: Hastings House Pub. Condition: Very Good. Good dust jacket. Seller Inventory S25D More information about this seller Contact this seller 6. Published by Dover Publications. About this Item: Dover Publications. Seller Inventory J14J More information about this seller Contact this seller 7. A copy that has been read but remains intact. May contain markings such as bookplates, stamps, limited notes and highlighting, or a few light stains. Seller Inventory D11B More information about this seller Contact this seller 8. Condition: Fair. A readable copy. All pages are intact, and the cover is intact. Pages can include considerable notes-in pen or highlighter-but the notes cannot obscure the text. -

Waterways Film List

Water/Ways Film List This film resource list was assembled to help you research and develop programming around the themes of the WATER/WAYS exhibition. Work with your local library, a movie theater, campus/community film clubs to host films and film discussions in conjunction with the exhibition. This list is not meant to be exhaustive or even all-encompassing – it will simply get you started. A quick search of the library card catalogue or internet will reveal numerous titles and lists compiled by experts, special interest groups and film buffs. Host series specific to your region or introduce new themes to your community. All titles are available on DVD unless otherwise specified. See children’s book list for some of the favorite animated short films. Many popular films have blogs, on-line talks, discussion ideas and classroom curriculum associated with the titles. Host sites should check with their state humanities council for recent Council- funded or produced documentaries on regional issues. 20,000 Leagues under the Sea. 1954. Adventure, Drama, Family. Not Rated. 127 minutes. Based on the 1870 classic science fiction novel by Jules Verne, this is the story of the fictional Captain Nemo (James Mason) and his submarine, Nautilus, and an epic undersea exploration. The oceans during the late 1860’s are no longer safe; many ships have been lost. Sailors have returned to port with stories of a vicious narwhal (a giant whale with a long horn) which sinks their ships. A naturalist, Professor Pierre Aronnax (Paul Lukas), his assistant, Conseil (Peter Lorre), and a professional whaler, Ned Land (Kirk Douglas), join an US expedition which attempts to unravel the mystery. -

Titanic Teacher Notes for Education Kit Tales of Titanic

TALES OF TITANIC MELBOURNE MUSEUM TEACHER NOTES 1 Tales of Titanic Education Kit, Melbourne Museum http://museumvictoria.com.au/titanic TABLE OF CONTENTS TALES OF TITANIC TEACHER NOTES .........................................3 Th ese education materials were Titanic: Th e Artefact Exhibition fl oor plan & Gallery descriptions ...........5 developed for teachers and students How to make the most of learning in museums ......................................6 visiting Titanic: Th e Artefact Exhibition at Melbourne Museum 2010. Conceptual learning framework for Tales of Titanic education kit ..........7 Learning focus and links to curriculum frameworks .............................12 Cover image: Maiden Voyage by Ted Walker Web links and other resources ..............................................................19 © Premier Exhibitions, Inc TITANIC INTEGRATED ................................................................23 Acknowledgements CSI Titanic: who died and how? ..........................................................24 Th e VELS On-site Education Activities “Iceberg right ahead”: using quotes from the Titanic ...........................27 and Tales of Titanic Education Kit Titanic online and interactive activities ................................................31 were researched and developed by Titanic: recovery and conservation .......................................................32 Jen Anderson, Pip Kelly and Liz Suda. Titanic photo and image analysis: using pictures to read the past .........36 Italian language activities