School of Graduate Studies Colorado State University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Captain Arthur Rostron

CAPTAIN ARTHUR ROSTRON CARPATHIA Created by: Jonathon Wild Campaign Director – Maelstrom www.maelstromdesign.co.uk CONTENTS 1 CAPTAIN ARTHUR ROSTRON………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….………3-6 CUNARD LINE…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………7-8 CAPTAIN ARTHUR ROSTRON CONT…….….……………………………………………………………………………………………………….8-9 RMS CARPATHIA…………………………………………………….…………………………………………………………………………………….9-10 SINKING OF THE RMS TITANIC………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…11-17 CAPTAIN ARTHUR ROSTRON CONT…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….18-23 R.M.S CARPATHIA – Copyright shipwreckworld.com 2 CAPTAIN ARTHUR ROSTRON Sir Arthur Henry Rostron, KBE, RD, RND, was a seafaring officer working for the Cunard Line. Up until 1912, he was an unknown person apart from in nautical circles and was a British sailor that had served in the British Merchant Navy and the Royal Naval Reserve for many years. However, his name is now part of the grand legacy of the Titanic story. The Titanic needs no introduction, it is possibly the most known single word used that can bring up memories of the sinking of the ship for the relatives, it will reveal a story that is still known and discussed to this day. And yet, Captain Rostron had no connections with the ship, or the White Star Line before 1912. On the night of 14th/15th April 1912, because of his selfless actions, he would be best remembered as the Captain of the RMS Carpathia who rescued many hundreds of people from the sinking of the RMS Titanic, after it collided with an iceberg in the middle of the North Atlantic Ocean. Image Copyright 9gag.com Rostron was born in Bolton on the 14th May 1869 in the town of Bolton. His birthplace was at Bank Cottage, Sharples to parents James and Nancy Rostron. -

Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses

Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. ABSTRACT THE ORIGIN, DEVELOPMENT, AND HISTORY OF THE NORWEGIAN SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH FROM THE 1840s TO 1887 by Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Adviser: Jerry Moon ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: THE ORIGIN, DEVELOPMENT, AND HISTORY OF THE NORWEGIAN SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH FROM THE 1840s TO 1887 Name of researcher: Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Name and degree of faculty adviser: Jerry Moon, Ph.D. Date completed: July 2010 This dissertation reconstructs chronologically the history of the Seventh-day Adventist Church in Norway from the Haugian Pietist revival in the early 1800s to the establishment of the first Seventh-day Adventist Conference in Norway in 1887. The present study has been based as far as possible on primary sources such as protocols, letters, legal documents, and articles in journals, magazines, and newspapers from the nineteenth century. A contextual-comparative approach was employed to evaluate the objectivity of a given source. Secondary sources have also been consulted for interpretation and as corroborating evidence, especially when no primary sources were available. The study concludes that the Pietist revival ignited by the Norwegian Lutheran lay preacher, Hans Nielsen Hauge (1771-1824), represented the culmination of the sixteenth- century Reformation in Norway, and the forerunner of the Adventist movement in that country. -

The Origin, Development, and History of the Norwegian Seventh-Day Adventist Church from the 1840S to 1889" (2010)

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 2010 The Origin, Development, and History of the Norwegian Seventh- day Adventist Church from the 1840s to 1889 Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Snorrason, Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik, "The Origin, Development, and History of the Norwegian Seventh-day Adventist Church from the 1840s to 1889" (2010). Dissertations. 144. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/144 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. ABSTRACT THE ORIGIN, DEVELOPMENT, AND HISTORY OF THE NORWEGIAN SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH FROM THE 1840s TO 1887 by Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Adviser: Jerry Moon ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: THE ORIGIN, DEVELOPMENT, AND HISTORY OF THE NORWEGIAN SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH FROM THE 1840s TO 1887 Name of researcher: Bjorgvin Martin Hjelvik Snorrason Name and degree of faculty adviser: Jerry Moon, Ph.D. Date completed: July 2010 This dissertation reconstructs chronologically the history of the Seventh-day Adventist Church in Norway from the Haugian Pietist revival in the early 1800s to the establishment of the first Seventh-day Adventist Conference in Norway in 1887. -

Ghosts of the Abyss. Titanic’S Bow As Seen from Mir II

A Dive to the titAnic Only a handful of craft can transport people to the deepest ocean realms, and I, as a maritime archaeologist, have been fortunate enough to dive in several of these deep submergence vehicles, also known as submersibles. My most exciting dive was to the wreck of the Titanic, which lies two and a half miles beneath the surface. The grand ocean liner sank in the early morning of April 15, 1912, after striking an iceberg, with a loss of more than 1,500 lives. In the fall of 2001, I was invited to take part in a Titanic expedition headed by James Cameron, director of the 1997 film Titanic. The goal of the expedition was to film the vessel’s remains using deep submersibles on which were mounted powerful lights and a unique high-definition 3D video camera. Cameron then produced a 3D IMAX documentary film, Ghosts of the Abyss. Titanic’s bow as seen from Mir II 8 dig www.digonsite.com Dig1105_Deep_DrDigRedo.indd 8 3/16/11 10:52 AM A Dive To The TiTAbynic John D. Broadwater t’s early morning on September 10, 2001, and I am aboard the 122-foot-long Russian research vessel Akademik Mstislav Keldysh. It is equipped with two submersibles, I Mir I and Mir II, both capable of descending 20,000 feet. The Mirs are 26 feet long, weigh more than 18 tons, and can carry three people—a pilot and two scientists or observers. I am participating in this expedition as a representative of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). -

Coordination Failure and the Sinking of Titanic

The Sinking of the Unsinkable Titanic: Mental Inertia and Coordination Failures Fu-Lai Tony Yu Department of Economics and Finance Hong Kong Shue Yan University Abstract This study investigates the sinking of the Titanic from the theory of human agency derived from Austrian economics, interpretation sociology and organizational theories. Unlike most arguments in organizational and management sciences, this study offers a subjectivist perspective of mental inertia to understand the Titanic disaster. Specifically, this study will argue that the fall of the Titanic was mainly due to a series of coordination and judgment failures that occurred simultaneously. Such systematic failures were manifested in the misinterpretations of the incoming events, as a result of mental inertia, by all parties concerned in the fatal accident, including lookouts, telegram officers, the Captain, lifeboat crewmen, architects, engineers, senior management people and owners of the ship. This study concludes that no matter how successful the past is, we should not take experience for granted entirely. Given the uncertain future, high alertness to potential dangers and crises will allow us to avoid iceberg mines in the sea and arrived onshore safely. Keywords: The R.M.S. Titanic; Maritime disaster; Coordination failure; Mental inertia; Judgmental error; Austrian and organizational economics 1. The Titanic Disaster So this is the ship they say is unsinkable. It is unsinkable. God himself could not sink this ship. From Butler (1998: 39) [The] Titanic… will stand as a monument and warning to human presumption. The Bishop of Winchester, Southampton, 1912 Although the sinking of the Royal Mail Steamer Titanic (thereafter as the Titanic) is not the largest loss of life in maritime history1, it is the most famous one2. -

Geographical List of Public Sculpture-1

GEOGRAPHICAL LIST OF SELECTED PERMANENTLY DISPLAYED MAJOR WORKS BY DANIEL CHESTER FRENCH ♦ The following works have been included: Publicly accessible sculpture in parks, public gardens, squares, cemeteries Sculpture that is part of a building’s architecture, or is featured on the exterior of a building, or on the accessible grounds of a building State City Specific Location Title of Work Date CALIFORNIA San Francisco Golden Gate Park, Intersection of John F. THOMAS STARR KING, bronze statue 1888-92 Kennedy and Music Concourse Drives DC Washington Gallaudet College, Kendall Green THOMAS GALLAUDET MEMORIAL; bronze 1885-89 group DC Washington President’s Park, (“The Ellipse”), Executive *FRANCIS DAVIS MILLET AND MAJOR 1912-13 Avenue and Ellipse Drive, at northwest ARCHIBALD BUTT MEMORIAL, marble junction fountain reliefs DC Washington Dupont Circle *ADMIRAL SAMUEL FRANCIS DUPONT 1917-21 MEMORIAL (SEA, WIND and SKY), marble fountain reliefs DC Washington Lincoln Memorial, Lincoln Memorial Circle *ABRAHAM LINCOLN, marble statue 1911-22 NW DC Washington President’s Park South *FIRST DIVISION MEMORIAL (VICTORY), 1921-24 bronze statue GEORGIA Atlanta Norfolk Southern Corporation Plaza, 1200 *SAMUEL SPENCER, bronze statue 1909-10 Peachtree Street NE GEORGIA Savannah Chippewa Square GOVERNOR JAMES EDWARD 1907-10 OGLETHORPE, bronze statue ILLINOIS Chicago Garfield Park Conservatory INDIAN CORN (WOMAN AND BULL), bronze 1893? group !1 State City Specific Location Title of Work Date ILLINOIS Chicago Washington Park, 51st Street and Dr. GENERAL GEORGE WASHINGTON, bronze 1903-04 Martin Luther King Jr. Drive, equestrian replica ILLINOIS Chicago Jackson Park THE REPUBLIC, gilded bronze statue 1915-18 ILLINOIS Chicago East Erie Street Victory (First Division Memorial); bronze 1921-24 reproduction ILLINOIS Danville In front of Federal Courthouse on Vermilion DANVILLE, ILLINOIS FOUNTAIN, by Paul 1913-15 Street Manship designed by D.C. -

Halifax, Nova Scotia and the Maritimes Have to Offer”

Quoted by Bob: “As with snowflakes, no two sightseeing tours are ever exactly the same, there's a personal touch added to each trip. Our tours are not of the "cookie cutter" variety - we're "home-made" and unique! All our tours will give you the very best sightseeing Halifax, Nova Scotia and the Maritimes have to offer”. That is the truth. There is no way that we could have planned this trip on our own. Bob made us feel very comfortable as passengers, the sightseeing was amazing, the meals and lodgings were great. Bob’s knowledge of area history, his personal stories and insights and great sense of humor left never a dull moment. We had so much fun it should have been illegal. In short Sheri and I both say “Bob’s our Uncle” and would not hesitate to hire or recommend Blue Diamond Tours in the future. The photograph above - Blue Diamond Tours is operated by THAT GUY in the tie. Day Zero – The Grand Arrival - July 4th 2012 The first leg of our flight was to depart Grande Prairie to Calgary at 7:00 am. The time shift from Chetwynd to Halifax is 4 hours and 3 hours from Grande Prairie. Our flight was delayed by about a ½ hour. That being said when we departed in Calgary the final boarding call for Halifax was being announced. No time to grab a bite or Pee – Just run. The flight to Halifax (4 ½ Hours) was mostly uneventful. Using a bathroom on a plane is slightly nicer than using an outhouse on the prairies – it smells better and lacks flies. -

Alaska to Nova Scotia

DESTINATION VenTure in OswegO, NY, wiTh sTill disTanCe to gO to compleTe This epeiC jOurney. AlaskaBY TONY FLEMINGto Nova Scotia They Tell iT like iT is in The Cayman islands. Part 2 – From the Panama Canal to nova SCotia mother oF a Sea trial the heart of the first major American city after ICW at Moorehead City south of Cape Fear in how about Some more intro Say three lineS so many weeks spent in remote places. North Carolina just as dawn was breaking. The total The Intra Coastal Waterway (ICW) runs all ICW alternates between narrow canal sections the way from Miami in Florida to Norfolk in with open areas so extensive that land is bare- ollowing our transit of the Panama Canal, of the night we picked up something on the Virginia and provides a slow, but protected, in- ly visible on the horizon. But, even in these Venture headed northeast through the port propeller. We backed down to get rid of it land route for much of the Eastern Seaboard. inland seas, the dredged channel zigzags ran- FCaribbean Sea to Grand Cayman Island but nothing surfaced and we could still feel a We were running a few days late on our sched- domly across the featureless water and may 600 miles away. The weather was rough on tremor on the port shaft. ule so we headed once more out into the open only be 50 yards wide with depths as little as this 60-hour leg and we encountered many We pulled into Bight Marina in Key West, Atlantic through the lock at Cape Canaveral 2 ft just beyond it. -

History of the Jews

II ADVERTISEMENTS Should be in Every Jewish Home AN EPOCH-MAKING WORK COVERING A PERIOD OF ABOUT FOUR THOUSAND YEARS PROF. HE1NRICH GRAETZ'S HISTORY OF THE JEWS THE MOST AUTHORITATIVE AND COMPREHENSIVE HISTORY OF THE JEWS IN THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE HANDSOMELY AND DURABLY BOUND IN SIX VOLUMES Contains more than 4000 pages, a Copious Index of more than 8000 Subjects, and a Number of Good Sized Colored Maps. SOME ENTHUSIASTIC APPRECIATIONS DIFFICULT TASK PERFORMED WITH CONSUMMATE SKILL "Graetz's 'Geschichte der Juden1 has superseded all former works of its kind, and has been translated into English, Russian and Hebrew, and partly into Yiddish and French. That some of these translations have been edited three or four times—a very rare occurrence in Jewish literature—are in themselves proofs of the worth of the work. The material for Jewish history being so varied, the sources so scattered in the literatures of all nations, made the presentation of this history a very difficult undertaking, and it cannot be denied that Graetz performed his task with consummate skill."—The Jewish Encyclopedia. GREATEST AUTHORITY ON SUBJECT "Professor Graetz is the historiographer par excellence of the Jews. His work, at present the authority upon the subject of Jewish History, bids fair to hold its pre-eminent position for some time, perhaps decades."—Preface to Index Volume. MOST DESIRABLE TEXT-BOOK "If one desires to study the history of the Jewish people under the direction of a scholar and pleasant writer who is in sympathy with his subject, because he is himself a Jew, he should resort to the volumes of Graetz."—"Review ofRevitvit (New York). -

Saving the Survivors Transferring to Steam Passenger Ships When He Joined the White Star Line in 1880

www.BretwaldaBooks.com @Bretwaldabooks bretwaldabooks.blogspot.co.uk/ Bretwalda Books on Facebook First Published 2020 Text Copyright © Rupert Matthews 2020 Rupert Matthews asserts his moral rights to be regarded as the author of this book. All rights reserved. No reproduction of any part of this publication is permitted without the prior written permission of the publisher: Bretwalda Books Unit 8, Fir Tree Close, Epsom, Surrey KT17 3LD [email protected] www.BretwaldaBooks.com ISBN 978-1-909698-63-5 Historian Rupert Matthews is an established public speaker, school visitor, history consultant and author of non-fiction books, magazine articles and newspaper columns. His work has been translated into 28 languages (including Sioux). Looking for a speaker who will engage your audience with an amusing, interesting and informative talk? Whatever the size or make up of your audience, Rupert is an ideal speaker to make your event as memorable as possible. Rupert’s talks are lively, informative and fun. They are carefully tailored to suit audiences of all backgrounds, ages and tastes. Rupert has spoken successfully to WI, Probus, Round Table, Rotary, U3A and social groups of all kinds as well as to lecture groups, library talks and educational establishments.All talks come in standard 20 minute, 40 minute and 60 minute versions, plus questions afterwards, but most can be made to suit any time slot you have available. 3 History Talks The History of Apples : King Arthur – Myth or Reality? : The History of Buttons : The Escape of Charles II - an oak tree, a smuggling boat and more close escapes than you would believe. -

Titanic Lessons.Indd

Lee AWA Review Titanic - Lessons for Emergency Communica- tions 2012 Bartholomew Lee Author She went to a freezing North Atlantic grave a hundred years ago, April 15, 1912, hav- By Bartholomew ing slit her hull open on an iceberg she couldn’t Lee, K6VK, Fellow avoid. Her story resonates across time: loss of of the California life, criminal arrogance, heroic wireless opera- Historical Radio tors, and her band playing on a sinking deck, Society, copyright serenading the survivors, the dying and the dead 2012 (no claim to as they themselves faced their own cold wet images) but any demise. The S.S. Titanic is the ship of legend.1 reasonable use The dedication to duty of the Marconi wire- may be made of less operators, Jack Phillips and Harold Bride, this note, respect- is both documented and itself legendary.2 Phil- ing its authorship lips stuck to his key even after Captain Edward and integrity, in Smith relieved him and Bride of duty as the ship furtherance of bet- sank. Phillips’ SOS and CQD signals brought the ter emergency com- rescue ships, in particular the S.S. Carpathia. munications. Phillips died of exposure in a lifeboat; Bride Plese see the survived.3 author description This note will present some of the Marconi at the end of the wireless messages of April 14. Any kind of work article, Wireless -- under stress is challenging. In particular stress its Evolution from degrades communications, even when effective Mysterious Won- communications can mean life or death. Art der to Weapon of Botterel4 once summed it up: “Stress makes you War, 1902 to 1905, stupid.” The only protection is training. -

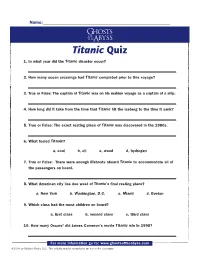

Ghosts of the Abyss: Titanic Quiz

Name:_______________________________________________________________ Titanic Quiz 1. In what year did the Titanic disaster occur? 2. How many ocean crossings had Titanic completed prior to this voyage? 3. True or False: The captain of Titanic was on his maiden voyage as a captain of a ship. 4. How long did it take from the time that Titanic hit the iceberg to the time it sank? 5. True or False: The exact resting place of Titanic was discovered in the 1980s. 6. What fueled Titanic? a. coal b. oil c. wood d. hydrogen 7. True or False: There were enough lifeboats aboard Titanic to accommodate all of the passengers on board. 8. What American city lies due west of Titanic’s final resting place? a. New York b. Washington, D.C. c. Miami d. Boston 9. Which class had the most children on board? a. first class b. second class c. third class 10. How many Oscars® did James Cameron’s movie Titanic win in 1998? For more information go to: www.ghostsoftheabyss.com ©2004 by Walden Media, LLC. This activity may be reproduced for use in the classroom. Titanic Quiz Answers 1. In what year did the Titanic disaster occur? 1912 2. How many ocean crossings had Titanic completed prior to this voyage? None: Titanic was on her maiden voyage. 3. True or False: The captain of Titanic was on his maiden voyage as a captain of a ship. False. After 38 years of service to the White Star Line, it was to be Captain Edward Smith’s final voyage. 4. How long did it take from the time that Titanic hit the iceberg to the time it sank? Titanic struck the iceberg at 11:40 PM on April 15 and sank approximately 2 hours and forty minutes later, at 2:20 AM on April 16.