Final Final Version for Lightningsource V6 November 14

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4Th October 2019 Turing House Friends MENSA PUZZLE Date for Your Diary – Year 7 Families! a Factory Recycles Paper Cups for Use in Its Canteen

Headteacher’s Update 4th October 2019 Turing House Friends MENSA PUZZLE Date for your diary – Year 7 Families! A factory recycles paper cups for use in its canteen. Seven used cups are needed to make each new cup. If there are 2,251 used cups, how many new cups can possibly be made? Last week’s answer: Wales. The initial of the name matches the third letter of the Country. Congratulations Welcome to the Turing House family - Matthew Turner was born on Thursday 26th. Congratulations Mr & Mrs Turner! Forthcoming Events Fixtures th 17 October – Sixth Form Open Evening 6pm – 8pm th 07 Oct, 2019 Y7/8 Football Teddington 18 October – INSET day th 19 October – CoderDojo 08 Oct, 2019 Y9 Netball Twickenham School th 24 October – Year 7 Family Bingo (Hampton) 08 Oct, 2019 Y10/11 Netball Twickenham School th st 28 Oct – 1 Nov – half term week 09 Oct, 2019 Y8 Rugby Union Richmond Thames School th 7 Nov – Y9 Parents’ Evening 09 Oct, 2019 Y7 Rugby Union Twickenham School turinghouseschool.org.uk Turing House School [email protected] Headteacher’s Update Turing House School 4th October 2019 World on Fire! The History of Bushy Park by Georgia Bools Peter Bowker’s emotionally gripping and resonant new Camp Griffiss was a US military base during and after BBC drama World on Fire begun on Sunday at 9pm on World War Two. Constructed within the grounds BBC1. The programme follows the intertwining fates of of Bushy Park in London, it served as the European ordinary people from Britain, Poland, France and Headquarters for the United States Air Army Germany during the first year of the Second World War Forces from July 1942 to December 1944. -

HAMPTON WICK the Thames Landscape Strategy Review 2 2 7

REACH 05 HAMPTON WICK The Thames Landscape Strategy Review 2 2 7 Landscape Character Reach No. 5 HAMPTON WICK 4.05.1 Overview 1994-2012 • Part redevelopment of the former Power Station site - refl ecting the pattern of the Kingston and Teddington reaches, where blocks of 5 storeys have been introduced into the river landscape. • A re-built Teddington School • Redevelopment of the former British Aerospace site next to the towpath, where the river end of the site is now a sports complex and community centre (The Hawker Centre). • Felling of a row of poplar trees on the former power station site adjacent to Canbury Gardens caused much controversy. • TLS funding bid to the Heritage Lottery Fund for enhancements to Canbury Gardens • Landscaping around Half Mile Tree has much improved the entrance to Kingston. • Construction of an upper path for cyclists and walkers between Teddington and Half Mile Tree • New visitor moorings as part of the Teddington Gateway project have enlivened the towpath route • Illegal moorings are increasingly a problem between Half Mile Tree and Teddington. • Half Mile Tree Enhancements 2007 • Timber-yards and boat-yards in Hampton Wick, the Power Station and British Aerospace in Kingston have disappeared and the riverside is more densely built up. LANDSCAPE CHARACTER 4.05.2 The Hampton Wick Reach curves from Kingston Railway Bridge to Teddington Lock. The reach is characterised by residential areas interspersed with recreation grounds. Yet despite tall apartment blocks at various locations on both banks dating from the last 30 years of the 20th century, the reach remains remarkably green and well-treed. -

GUNNERSBURY PARK Options Appraisal

GUNNERSBURY PARK Options Appraisal Report By Jura Consultants and LDN Architects June 2009 LDN Architects 16 Dublin Street Edinburgh EH1 3RE 0131 556 8631 JURA CONSULTANTS www.ldn.co.uk 7 Straiton View Straiton Business Park Loanhead Midlothian Edinburgh Montagu Evans LLP EH20 9QZ Clarges House 6-12 Clarges Street TEL. 0131 440 6750 London, W1J 8HB FAX. 0131 440 6751 [email protected] 020 7493 4002 www.jura-consultants.co.uk www.montagu-evans.co.uk CONTENTS Section Page Executive Summary i. 1. Introduction 1. 2. Background 5. 3. Strategic Context 17. 4. Development of Options and Scenarios 31. 5. Appraisal of Development Scenarios 43. 6. Options Development 73. 7. Enabling Development 87. 8. Preferred Option 99. 9. Conclusions and Recommendations 103. Appendix A Stakeholder Consultations Appendix B Training Opportunities Appendix C Gunnersbury Park Covenant Appendix D Other Stakeholder Organisations Appendix E Market Appraisal Appendix F Conservation Management Plan The Future of Gunnersbury Park Consultation to be conducted in the Summer of 2009 refers to Options 1, 2, 3 and 4. These options relate to the options presented in this report as follows: Report Section 6 Description Consultation Option A Minimum Intervention Option 1 Option B Mixed Use Development Option 2 Option C Restoration and Upgrading Option 4 Option D Destination Development Option 3 Executive Summary EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Introduction A study team led by Jura Consultants with LDN Architects and Montagu Evans was commissioned by Ealing and Hounslow Borough Councils to carry out an options appraisal for Gunnersbury Park. Gunnersbury Park is situated within the London Borough of Hounslow and is unique in being jointly owned by Ealing and Hounslow. -

N11 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

N11 bus time schedule & line map N11 Liverpool Street - Ealing Broadway View In Website Mode The N11 bus line (Liverpool Street - Ealing Broadway) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Ealing Broadway: 12:21 AM - 4:51 AM (2) Liverpool Street: 12:15 AM - 11:45 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest N11 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next N11 bus arriving. Direction: Ealing Broadway N11 bus Time Schedule 81 stops Ealing Broadway Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:21 AM - 4:51 AM Monday 12:21 AM - 4:51 AM Liverpool Street Station (L) 192 Bishopsgate, London Tuesday 12:21 AM - 4:51 AM Wormwood Street (Y) Wednesday 12:21 AM - 4:51 AM 99 Bishopsgate, London Thursday 12:21 AM - 4:51 AM Old Broad Street (LL) Friday 12:21 AM - 4:51 AM 5 Old Broad Street, London Saturday 12:21 AM - 4:51 AM Bank Station / Queen Victoria Street 1 Poultry, London St Paul's Churchyard (SH) Old Change Court, London N11 bus Info Direction: Ealing Broadway St Paul's Cathedral (SJ) Stops: 81 10 Saint Paul's Church Yard, London Trip Duration: 83 min Line Summary: Liverpool Street Station (L), City Thameslink Stn / Ludgate Circus (F) Wormwood Street (Y), Old Broad Street (LL), Bank 65 Ludgate Hill, London Station / Queen Victoria Street, St Paul's Churchyard (SH), St Paul's Cathedral (SJ), City Thameslink Stn / Shoe Lane (H) Ludgate Circus (F), Shoe Lane (H), Fetter Lane (W), Fleet Street, London Chancery Lane (W), The Royal Courts Of Justice (P), Aldwych / Drury Lane (R), Savoy Street (U), Bedford Fetter Lane (W) Street -

Buses from Strawberry Hill

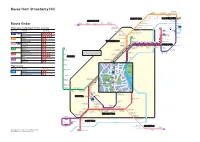

Buses from Strawberry Hill Hammersmith Stamford Brook Hammersmith Grove Gunnersbury Bus Garage for Hammersmith & City line Turnham Green Ravenscourt Church Park Kew Bridge for Steam Museum 24 hour Brentford Watermans Arts Centre HAMMERSMITH 33 service BRENTFORD Hammersmith 267 Brentford Half Acre Bus Station for District and Piccadilly lines HOUNSLOW Syon Park Hounslow Hounslow Whitton Whitton Road River Thames Bus Station Treaty Centre Hounslow Church Admiral Nelson Isleworth Busch Corner 24 hour Route finder 281 service West Middlesex University Hospital Castelnau Isleworth War Memorial N22 Twickenham Barnes continues to Rugby Ground R68 Bridge Day buses including 24-hour services Isleworth Library Kew Piccadilly Retail Park Circus Bus route Towards Bus stops London Road Ivy Bridge Barnes Whitton Road Mortlake Red Lion Chudleigh Road London Road Hill View Road 24 hour service ,sl ,sm ,sn ,sp ,sz 33 Fulwell London Road Whitton Road R70 Richmond Whitton Road Manor Circus ,se ,sf ,sh ,sj ,sk Heatham House for North Sheen Hammersmith 290 Twickenham Barnes Fulwell ,gb ,sc Twickenham Rugby Tavern Richmond 267 Lower Mortlake Road Hammersmith ,ga ,sd TWICKENHAM Richmond Road Richmond Road Richmond Road Richmond Twickenham Lebanon Court Crown Road Cresswell Road 24 hour Police Station 281 service Hounslow ,ga ,sd Twickenham RICHMOND Barnes Common Tolworth ,gb ,sc King Street Richmond Road Richmond Road Richmond Orleans Park School St Stephen’s George Street Twickenham Church Richmond 290 Sheen Road Staines ,gb ,sc Staines York Street East Sheen 290 Bus Station Heath Road Sheen Lane for Copthall Gardens Mortlake Twickenham ,ga ,sd The yellow tinted area includes every Sheen Road bus stop up to about one-and-a-half Cross Deep Queens Road for miles from Strawberry Hill. -

29 Newgate and Westminster 1820

678 December 14th 1819-December 31st 1820: Newgate, Cato Street, and the Trial of Queen Caroline 1820: Newgate Diary, the 1820 Westminster Election, Byron’s ballad My Boy Hobby, O, the execution of the Cato Street Conspirators, and the Trial of Queen Caroline December 14th 1819-December 31st 1820 Edited from B.L.Add.Mss. 56540 and 56541. In the notes, “I.G.” indicates assistance from Ian Gilmour, to whom I’m grateful. In 1819 Hobhouse contested the parliamentary seat of Westminster, which had become vacant on the suicide of Romilly. He stood as a radical, supported by his father and by Burdett, but was defeated on March 3rd by George Lamb. Riots followed, and a breach opened between him and the Holland House Whigs. Westminster was an unusual constituency. It extended from Temple Bar to Hyde Park, from Oxford Street to the Thames, and three-quarters of its voters were middle-class: shopkeepers, skilled artisans, printers, tailors, and so on. It was the only constituency in the country in which each of its 17,000 rate-paying householders had the vote, which fact made it a headache to any administration, Whig or Tory, which was based upon, and served, as all administrations were and did, the landed gentry. At Westminster, candidates had to stand on the hustings and speak deferentially to people whom they’d normally expect to speak deferentially to them . At this time Hobhouse wrote several pamphlets, and an anonymous reply to a sarcastic speech of Canning’s, written by him and some of his friends in the Rota Club, attracted attention. -

Lancaster House Venue Hire

Lancaster House Venue Hire “I have come from my house to your palace” —Queen Victoria Steeped in political history, discover magnificent Lancaster House with fabulous Louis XIV style interiors, stunning art collection, beautiful terrace and garden. Situated adjacent to Buckingham Palace, this historic house provides an impressive setting and first-class facilities for your event, reception, conference or other special occasion. The Grand Hall and Staircase On entering the house through the portico, the Grand Hall opens up to reveal a sweeping staircase and balustrade, in an echo of the Palace of Versailles. Both features are part of architect’s Benjamin Wyatt’s original design. Over the past two centuries numerous high-profile occasions have taken place here, from society banquets to international summits and receptions. With its ornate ceiling, marble walls and beautiful frescoes, the Grand Hall is a wonderful location to hold receptions, with a capacity of 200 available to experience the splendour of Lancaster House. To enquire about booking the Grand Hall and other fine rooms contact the team on +44 (0)20 7008 2711 from 0800–1700 Monday to Friday or email lancasterhouse. [email protected]. The Long Gallery More than 35 metres in length, the Long Gallery dominates the whole of the east side of the house. With 18 windows and a large ornate skylight, the room is filled with natural light. Winston Churchill gave a Coronation Banquet for the newly crowned Queen Elizabeth II here in June 1953. Long Gallery maximum capacities Reception Boardroom Theatre-style Seated meal 350 60* 200 150 *plus a further 120 people seated beside and behind table The Music Room With windows opening onto a balcony and recesses flanked by Corinthian columns, the music room is the wonderful venue for meetings, press briefings or formal dinners. -

Dtd Final Proof 5 August 2016

BOROUGH OF TWICKENHAM LOCAL HISTORY SOCIETY Paper Number 97 Down The Drain The Long And Difficult Transition from Night Soil Men to Public Sewage Treatment Schemes: Local Democracy stretched to its limits in Hampton Wick, Teddington, Twickenham (with Whitton) and Hampton 1863-99 Ray Elmitt © Borough of Twickenham Local History Society 2016 ISBN: 978-0-903341-96-7 Price £10 Contents PREFACE 5 INTRODUCTION 6 1. HAMPTON WICK 12 Origins 13 Hampton Wick in 1863 15 Drainage of Hampton Wick 17 The Threat of the Thames Conservators 20 Impasse 25 Attempts to Create Joint Action 26 The Baton Passes 27 A Solution Emerges 28 The Latest Drainage Committee Struggles 30 Preparations Are Made 34 Trial by Local Government Board 37 Action at Last 40 An Unexpected End 43 Postscript 45 2. TEDDINGTON 49 Origins 49 A Local Board Is Formed 50 A Sewerage Scheme Is Proposed 52 Details of the Scheme 54 Applying for the Loan Sanction 57 Tenders and Contracts 60 Work Is Underway 62 The Issue of Private Roads 65 The Contractual Wrangle 67 A New Contractor Is Engaged 70 The Arbitration Award 71 The Outcome 78 The Sewage Works Site 79 Postscript 79 2 3. TWICKENHAM 83 Prologue 83 Introduction 85 The Formation of a Local Board 85 Renewed Efforts 90 Back to Basics 98 Resignation 100 Action at Last 103 The New Disposal System 107 The Final Stages 111 Epilogue 112 4. HAMPTON 117 Introduction 117 Hampton Debates The Formation of a Local Board 117 Life Under the Kingston Rural Sanitary Authority 120 A Local Board Is Formed 124 Early Years of Hampton Local Board 125 The First Public Inquiry 126 A Revised Scheme Is Approved 129 Implementing the Drainage Scheme 135 Postscript 141 5. -

E Historic Maps and Plans

E Historic Maps and Plans Contains 12 Pages Map 1a: 1771 ‘Plan of the Royal Manor of Richmond’ by Burrell and Richardson. Map 1b: Extract of 1771 ‘Plan of the Royal Manor of Richmond’ by Burrell and Richardson. Map 2. 1837 ‘Royal Gardens, View’ Map 3. 1861-1871 1st Edition Ordnance Survey map Map 4. c.1794 ‘A Plan of Richmond and Kew Gardens’ Map 5. 1844 ‘Sketch plan of the ground attached to the proposed Palm House at Kew and also for the Pleasure Ground - showing the manner in which a National Arboretum may be formed without materially altering the general features’ by Nesfield. Map 6. ‘Royal Botanic Gardens: The dates and extent of successive additions to the Royal Gardens from their foundation in 1760 (9 acres) to the present time (288 acres)’ Illustration 1. 1763 ‘A View of the Lake and Island, with the Orangerie, the Temples of Eolus and Bellona, and the House of Confucius’ by William Marlow Illustration 2. ‘A Perspective View of the Palace from the Northside of the Lake, the Green House and the Temple of Arethusa, in the Royal Gardens at Kew’ by William Woollett Illustration 3. c.1750 ‘A view of the Palace from the Lawn in the Royal Gardens at Kew’ by James Roberts Illustration 4. Great Palm House, Kew Gardens Illustration 5. Undated ‘Kew Palace and Gardens’ May 2018 Proof of Evidence: Historic Environment Kew Curve-PoE_Apps_Final_05-18-AC Chris Blandford Associates Map 1a: 1771 ‘Plan of the Royal Manor of Richmond’ by Burrell and Richardson. Image courtesy of RBGK Archive is plan shows the two royal gardens st before gsta died in 1 and aer eorge had inherited ichmond Kew ardens have been completed by gsta and in ichmond apability rown has relandscaped the park for eorge e high walls of ove ane are still in place dividing the two gardens May 2018 Appendix E AppE-L.indd MAP 1a 1 Map 1b: Extract of 1771 ‘Plan of the Royal Manor of Richmond’ by Burrell and Richardson. -

St James Conservation Area Audit

ST JAMES’S 17 CONSERVATION AREA AUDIT AREA CONSERVATION Document Title: St James Conservation Area Audit Status: Adopted Supplementary Planning Guidance Document ID No.: 2471 This report is based on a draft prepared by B D P. Following a consultation programme undertaken by the council it was adopted as Supplementary Planning Guidance by the Cabinet Member for City Development on 27 November 2002. Published December 2002 © Westminster City Council Department of Planning & Transportation, Development Planning Services, City Hall, 64 Victoria Street, London SW1E 6QP www.westminster.gov.uk PREFACE Since the designation of the first conservation areas in 1967 the City Council has undertaken a comprehensive programme of conservation area designation, extensions and policy development. There are now 53 conservation areas in Westminster, covering 76% of the City. These conservation areas are the subject of detailed policies in the Unitary Development Plan and in Supplementary Planning Guidance. In addition to the basic activity of designation and the formulation of general policy, the City Council is required to undertake conservation area appraisals and to devise local policies in order to protect the unique character of each area. Although this process was first undertaken with the various designation reports, more recent national guidance (as found in Planning Policy Guidance Note 15 and the English Heritage Conservation Area Practice and Conservation Area Appraisal documents) requires detailed appraisals of each conservation area in the form of formally approved and published documents. This enhanced process involves the review of original designation procedures and boundaries; analysis of historical development; identification of all listed buildings and those unlisted buildings making a positive contribution to an area; and the identification and description of key townscape features, including street patterns, trees, open spaces and building types. -

D-Day Marshalling and Embarkation Areas

SECOND WORLD WAR - D-Day Marshalling and Embarkation Areas 1. Operation Overlord From April 1944, the east-coast, the south and west coastal areas of England and parts of south Wales were divided into a number of concentration areas known as Marshalling Areas (MAs). One or more MAs served an Embarkation Area (EA). Preliminary planning as regards to the layout of each area had been worked out the previous year, such as exercise 'Harlequin' – carried out within the Sussex District and Central Sussex Sub- District during August and September 1943. By mid-March 1944, the Overlord Marshalling & Concentration Area plans were being finalised, this was called the 'Sausage Plan' on account of the shape given to the MA boundaries when identified on a map. Command Responsibilities Eastern Command was required to provide concentration areas for all troops passing through Tilbury and London Docks. This included an infantry division plus accumulated residues totalling 104,000 troops. Felixstowe and Tilbury Docks were each to be allocated one reinforcement holding unit of 1,600 troops and one reinforcement group of three units of 4,800 troops within the concentration area. Southern Command's primary responsibility was to provide concentration areas for US Forces by direct arrangement with SOS ETOUSA. This was in addition to two British armoured brigades located in the Bournemouth /Poole Area, and 21 Army Group. One reinforcement holding unit was also required to be accommodated in each of the Portsmouth and Southampton MAs. British Airborne Forces required tented accommodation for 800 (all ranks) at certain airfields within the command from which the forces would operate. -

Hampton Village Consultation Material

Hampton Village INTRODUCTION TO VILLAGE PLANNING GUIDANCE FOR HAMPTON What is Village Planning Guidance? How can I get involved? London Borough of Richmond upon Thames (LBRuT) wants residents and businesses to help prepare ‘Village Planning There will be two different stages of engagement and consultation Guidance’ for the Hampton Village area. This will be a before the guidance is adopted. document that the Council considers when deciding on planning During February and March residents and businesses are being asked applications. Village Planning Guidance can: about their vision for the future of their area, thinking about: • Help to identify what the ‘local character’ of your area is and • the local character what features need to be retained. • heritage assets • Help protect and enhance the local character of your area, • improvement opportunities for specific sites or areas particularly if it is not a designated ‘Conservation Area’. • other planning policy or general village plan issues • Establish key design principles that new development should respond to. Draft guidance will be developed over the summer based on your views and a formal (statutory) consultation carried out in late The boundary has been based on the Village Plan area to reflect summer/autumn 2016 before adoption later in the year. the views of where people live, as well as practical considerations to support the local interpretation of planning policy. How does Village Planning Guidance work? How does the ‘Village Planning Guidance’ relate to Village Plans? The Village Planning Guidance will become a formal planning policy ‘Supplementary Planning Document’ (SPD) which The Planning Guidance builds on the ‘Village Plans’ which were the Council will take account of when deciding on planning developed from the 2010 ‘All in One’ survey results, and from ongoing applications, so it will influence developers and householders consultation, including through the engagement events currently in preparing plans and designs.