1403To 1707A.D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-16336-2 — Medieval Historical Writing Edited by Jennifer Jahner , Emily Steiner , Elizabeth M

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-16336-2 — Medieval Historical Writing Edited by Jennifer Jahner , Emily Steiner , Elizabeth M. Tyler Index More Information Index 1381 Rising. See Peasants’ Revolt Alcuin, 123, 159, 171 Alexander Minorita of Bremen, 66 Abbo of Fleury, 169 Alexander the Great (Alexander III), 123–4, Abbreviatio chronicarum (Matthew Paris), 230, 233 319, 324 Alfred of Beverley, Annales, 72, 73, 78 Abbreviationes chronicarum (Ralph de Alfred the Great, 105, 114, 151, 155, 159–60, 162–3, Diceto), 325 167, 171, 173, 174, 175, 176–7, 183, 190, 244, Abelard. See Peter Abelard 256, 307 Abingdon Apocalypse, 58 Allan, Alison, 98–9 Adam of Usk, 465, 467 Allen, Michael I., 56 Adam the Cellarer, 49 Alnwick, William, 205 Adomnán, Life of Columba, 301–2, 422 ‘Altitonantis’, 407–9 Ælfflæd, abbess of Whitby, 305 Ambrosius Aurelianus, 28, 33 Ælfric of Eynsham, 48, 152, 171, 180, 306, 423, Amis and Amiloun, 398 425, 426 Amphibalus, Saint, 325, 330 De oratione Moysi, 161 Amra Choluim Chille (Eulogy of St Lives of the Saints, 423 Columba), 287 Aelred of Rievaulx, 42–3, 47 An Dubhaltach Óg Mac Fhirbhisigh (Dudly De genealogia regum Anglorum, 325 Ferbisie or McCryushy), 291 Mirror of Charity, 42–3 anachronism, 418–19 Spiritual Friendship, 43 ancestral romances, 390, 391, 398 Aeneid (Virgil), 122 Andreas, 425 Æthelbald, 175, 178, 413 Andrew of Wyntoun, 230, 232, 237 Æthelred, 160, 163, 173, 182, 307, 311 Angevin England, 94, 390, 391, 392, 393 Æthelstan, 114, 148–9, 152, 162 Angles, 32, 103–4, 146, 304–5, 308, 315–16 Æthelthryth (Etheldrede), -

The Matter of Britain

THE MATTER OF BRITAIN: KING ARTHUR'S BATTLES I had rather myself be the historian of the Britons than nobody, although so many are to be found who might much more satisfactorily discharge the labour thus imposed on me; I humbly entreat my readers, whose ears I may offend by the inelegance of my words, that they will fulfil the wish of my seniors, and grant me the easy task of listening with candour to my history May, therefore, candour be shown where the inelegance of my words is insufficient, and may the truth of this history, which my rustic tongue has ventured, as a kind of plough, to trace out in furrows, lose none of its influence from that cause, in the ears of my hearers. For it is better to drink a wholesome draught of truth from a humble vessel, than poison mixed with honey from a golden goblet Nennius CONTENTS Chapter Introduction 1 The Kinship of the King 2 Arthur’s Battles 3 The River Glein 4 The River Dubglas 5 Bassas 6 Guinnion 7 Caledonian Wood 8 Loch Lomond 9 Portrush 10 Cwm Kerwyn 11 Caer Legion 12 Tribuit 13 Mount Agned 14 Mount Badon 15 Camlann Epilogue Appendices A Uther Pendragon B Arthwys, King of the Pennines C Arthur’s Pilgrimages D King Arthur’s Bones INTRODUCTION Cupbearer, fill these eager mead-horns, for I have a song to sing. Let us plunge helmet first into the Dark Ages, as the candle of Roman civilisation goes out over Europe, as an empire finally fell. The Britons, placid citizens after centuries of the Pax Romana, are suddenly assaulted on three sides; from the west the Irish, from the north the Picts & from across the North Sea the Anglo-Saxons. -

St Margaret of Scotland, Morgan Colman's

2021 VIII The Saxon Connection: St Margaret of Scotland, Morgan Colman’s Genealogies, and James VI & I’s Anglo-Scottish Union Project Joseph B. R. Massey Article: The Saxon Connection: St Margaret of Scotland, Morgan Colman’s Genealogies, and James VI & I’s Anglo-Scottish Union Project The Saxon Connection: St Margaret of Scotland, Morgan Colman’s Genealogies, and James VI & I’s Anglo-Scottish Union Project Joseph B.R. Massey MANCHESTER METROPOLITAN UNIVERSITY Abstract: James VI of Scotland’s succession to the English throne as James I in 1603 was usually justified by contemporaries on the grounds that James was Henry VII’s senior surviving descendant, making him the rightful hereditary claimant. Some works, however, argued that James also had the senior Saxon hereditary claim to the English throne due his descent from St Margaret of Scotland—making his hereditary claim superior to that of any English monarch from William the Conqueror onwards. Morgan Colman’s Arbor Regalis, a large and impressive genealogy, was a visual assertion of this argument, showing that James’s senior hereditary claims to the thrones of both England and Scotland went all the way back to the very foundations of the two kingdoms. This article argues that Colman’s genealogy could also be interpreted in support of James’s Anglo-Scottish union project, showing that the permanent union of England and Scotland as Great Britain was both historically legitimate and a justifiable outcome of James’s combined hereditary claims. Keywords: Jacobean; genealogies; Great Britain; hereditary right; succession n 24 March 1603, Queen Elizabeth I of England died and her Privy Council proclaimed that James VI, King of Scots, had succeeded as King of England. -

Scotland: Bruce 286

Scotland: Bruce 286 Scotland: Bruce Robert the Bruce “Robert I (1274 – 1329) the Bruce holds an honored place in Scottish history as the king (1306 – 1329) who resisted the English and freed Scotland from their rule. He hailed from the Bruce family, one of several who vied for the Scottish throne in the 1200s. His grandfather, also named Robert the Bruce, had been an unsuccessful claimant to the Scottish throne in 1290. Robert I Bruce became earl of Carrick in 1292 at the age of 18, later becoming lord of Annandale and of the Bruce territories in England when his father died in 1304. “In 1296, Robert pledged his loyalty to King Edward I of England, but the following year he joined the struggle for national independence. He fought at his father’s side when the latter tried to depose the Scottish king, John Baliol. Baliol’s fall opened the way for fierce political infighting. In 1306, Robert quarreled with and eventually murdered the Scottish patriot John Comyn, Lord of Badenoch, in their struggle for leadership. Robert claimed the throne and traveled to Scone where he was crowned king on March 27, 1306, in open defiance of King Edward. “A few months later the English defeated Robert’s forces at Methven. Robert fled to the west, taking refuge on the island of Rathlin off the coast of Ireland. Edward then confiscated Bruce property, punished Robert’s followers, and executed his three brothers. A legend has Robert learning courage and perseverance from a determined spider he watched during his exile. “Robert returned to Scotland in 1307 and won a victory at Loudon Hill. -

Converted by Filemerlin

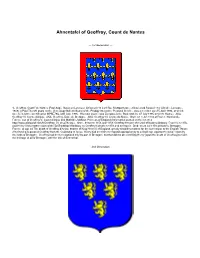

Ahnentafel of Geoffroy, Count de Nantes --- 1st Generation --- 1. Geoffroy, Count1 de Nantes (Paul Augé, Nouveau Larousse Universel (13 à 21 Rue Montparnasse et Boulevard Raspail 114: Librairie Larousse, 1948).) (Paul Theroff, posts on the Genealogy Bulletin Board of the Prodigy Interactive Personal Service, was a member as of 5 April 1994, at which time he held the identification MPSE79A, until July, 1996. His main source was Europaseische Stammtafeln, 07 July 1995 at 00:30 Hours.). AKA: Geoffroy VI, Comte d'Anjou. AKA: Geoffroy, Duke de Bretagne. AKA: Geoffroy VI, Comte du Maine. Born: on 3 Jun 1134 at Rouen, Normandie, France, son of Geoffroy V, Count d'Anjou and Mathilde=Mahaut, Princess of England (Information posted on the Internet, http://www.wikiwand.com/fr/Geoffroy_VI_d%27Anjou.). Note - between 1156 and 1158: Geoffroy became the Lord of Nantes (Brittany, France) in 1156, and Henry II his brother claimed the overlordship of Brittany on Geoffrey's death in 1158 and overran it. Died: on 26 Jul 1158 at Nantes, Bretagne, France, at age 24 The death of Geoffroy d'Anjou, brother of King Henry II of England, greatly simplifies matters for the succession to the English Throne. After having separated Geoffroy from the Countship of Anjou, Henry had sent him to respond appropriatetly to a challenge against the ducal crown by the lords of Bretagne. Geoffroy had been recognized only by part of Bretagne, but that did not prevent King Henry [upon the death of Geoffroy] to claim the heritage of all of Bretagne, with the title of Seneschal. --- 2nd Generation --- Coat of Arm associated with Geoffroy V, Comte d'Anjou. -

Agatha: Slavic Versus Salian Solutions -31

AGATHA: SLAVIC VERSUS SALIAN SOLUTIONS -31- AGATHA, MOTHER OF ST. MARGARET: THE SLAVIC VERSUS SALIAN SOLUTIONS – A CRITICAL OVERVIEW by William Humphreys, BA(Hons), MSI1 ABSTRACT The published evidence is reviewed and critically assessed regarding the ancestry of Agatha, mother of St. Margaret, Queen of Scotland. The debate continues, and although the solution remains in doubt, the author concludes that on balance the evidence is stronger for the Slavic ancestry rather than the Germanic (Salian) one. Foundations (2003) 1 (1): 31-43 © Copyright FMG As we enter the 21st century we are no nearer to identifying, or agreeing upon, the maternal ancestry of one of the most important characters in Scottish medieval history – St. Margaret, wife of King Malcolm III (d.1093). The dynastic usurpation and post- invasion trauma of 1066 dictated that St. Margaret’s maternal origins were of secondary importance to English Chroniclers until the marriage of her daughter Edith-Matilda to Henry I in 1100. The debate as to the maternal ancestry of St. Margaret is now becoming more relevant as the known pool of descendants grows ever larger and align themselves, as do many writers, to one of two basic, generic solutions – Slavic or Salian. The last six years have seen a re-igniting of the debate with seven major articles being published2. Historiographers may already look back at the flurry of articles in the late 1930s/early 1950s as a sub-conscious attempt by the writers of the time to align with or distance themselves from Germany. Several (Fest, 1938; Moriarty, 1952) sought to establish Agatha as an otherwise unknown daughter of St. -

Euriskodata Rare Book Series

Jsl THE ANTIQUITIES OF AEEAN. *. / f?m Finfcal's and Bruce's Cave. THE ANTIQUITIES OF ARRAN: Skekjj of fyt EMBRACING AN ACCOUNT OP THE SUDEEYJAE UNDER THE NOESEMEN, BY JOHN M'ARTHUR ' Enquire, I pray thee, of the former age, and prepare thyself to the search of their fathers : for we are but of yesterday." JOB viii. 8, 9. ames acr, n. GLASGOW: THOMAS MUKRAY AND SON. EDINBURGH: PATON AND RITCHIE. LONDON: ARTHUR HALL, VIRTUE AND co. 1861. PREFATORY NOTE. WHILST spending a few days in Arran, the attention of the Author was drawn to the numerous pre-historic monuments scattered over the Island. The present small Work embraces an account of these in- teresting remains, prepared chiefly from careful personal observation. The concluding Part contains a description of the monu- ments of a later period the chapels and castles of the Island to which a few brief historical notices have been appended. Should the persual of these pages induce a more thorough investigation into these stone-records of the ancient history of Arran, the object of the Author shall have been amply attained. The Author begs here gratefully to acknowledge the kind- ness and assistance rendered him by JOHN BUCHANAN, Esq. of Glasgow; JAMES NAPIEE, Esq., F.C.S., &c., Killin; the Rev. COLIN F. CAMPBELL of Kilbride, and the Rev. CHARLES STEWART, Kilmorie Arran. 4 RADNOB TERBACE, GLASGOW, June, 1861. 2058000 CONTENTS. Page PREFATORY NOTE, 5 i|u Stair* CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION, .... ..... 11 " II. BARROWS AND CAIRNS, ....... 18 " III. CROMLECHS, .......... 37 IV. STANDING STONES, ........ 42 " V. STONE CIRCLES, ........ -

Clan Dunbar 2014 Tour of Scotland in August 14-26, 2014: Journal of Lyle Dunbar

Clan Dunbar 2014 Tour of Scotland in August 14-26, 2014: Journal of Lyle Dunbar Introduction The Clan Dunbar 2014 Tour of Scotland from August 14-26, 2014, was organized for Clan Dunbar members with the primary objective to visit sites associated with the Dunbar family history in Scotland. This Clan Dunbar 2014 Tour of Scotland focused on Dunbar family history at sites in southeast Scotland around Dunbar town and Dunbar Castle, and in the northern highlands and Moray. Lyle Dunbar, a Clan Dunbar member from San Diego, CA, participated in both the 2014 tour, as well as a previous Clan Dunbar 2009 Tour of Scotland, which focused on the Dunbar family history in the southern border regions of Scotland, the northern border regions of England, the Isle of Mann, and the areas in southeast Scotland around the town of Dunbar and Dunbar Castle. The research from the 2009 trip was included in Lyle Dunbar’s book entitled House of Dunbar- The Rise and Fall of a Scottish Noble Family, Part I-The Earls of Dunbar, recently published in May, 2014. Part I documented the early Dunbar family history associated with the Earls of Dunbar from the founding of the earldom in 1072, through the forfeiture of the earldom forced by King James I of Scotland in 1435. Lyle Dunbar is in the process of completing a second installment of the book entitled House of Dunbar- The Rise and Fall of a Scottish Noble Family, Part II- After the Fall, which will document the history of the Dunbar family in Scotland after the fall of the earldom of Dunbar in 1435, through the mid-1700s, when many Scots, including his ancestors, left Scotland for America. -

St Kentigern

St. Kentigern St. Kentigern, was born c. 518. According to the Life of Saint Mungo written by the monk, Jocelin of Furness, in about 1185, Mungo’s mother was Princess Theneva, the daughter of King Loth (Lleuddun), who ruled in the area of, what is today, East Lothian. Theneva became pregnant - accounts vary as to whether she was raped by, or had an illicit relationship with, Owain mab Urien, her cousin, who was King of North Rheged (now part of Galloway). Her father, who was furious at his daughter’s pregnancy outside of marriage, had her thrown from the heights of Traprain Law. Tradition has it that, believing her to be a witch, local people cast her adrift on the River Forth in a coracle without oars, where she drifted upstream before coming ashore at Culross in Fife. It was here that her son, Kentigern, was born. Kentigern was given the name Mungo, meaning something similar to ‘dear one’, by St. Serf, who ran a monastery at Culross, and who took both Theneva and her son into his care. St. Serf went on to supervise Mungo’s upbringing. At the age of 25, Mungo began his missionary work on the banks of the River Clyde, where he built a church close to the Molendinar Burn. The site of his early church formed part of Glasgow Cathedral. Mungo worked on the banks of the River Clyde for 13 years, living an austere monastic life and making many converts by his holy example and preaching. However, a strong anti-Christian movement headed by King Morken of Strathclyde drove him out. -

The Church in Sixteenth-Century Glasgow

Servants to St. Mungo: The Church in Sixteenth-Century Glasgow by Daniel MacLeod A Thesis presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Daniel MacLeod, May, 2013 ABSTRACT SERVANTS TO ST MUNGO: THE CHURCH IN SIXTEENTH-CENTURY GLASGOW Daniel MacLeod Advisors: University of Guelph, 2013 Dr. Elizabeth Ewan Dr. Peter Goddard This thesis investigates religious life in Glasgow, Scotland in the sixteenth century. As the first full length study of the town’s Christian community in this period, this thesis makes use of the extant Church documents to examine how Glaswegians experienced Christianity during the century in which religious change was experienced by many communities in Western Europe. This project includes research from both before and after 1560, the year of the Reformation Parliament in Scotland, and therefore eschews traditional divisions used in studies of this kind that tend to view 1560 as a major rupture for Scotland’s religious community. Instead, this study reveals the complex relationships between continuity and change in Glasgow, showing a vibrant Christian community in the early part of the century and a changed but similarly vibrant community at the century’s end. This project attempts to understand Glasgow’s religious community holistically. It investigates the institutional structures of the Church through its priests and bishops as well as the popular devotions of its parishioners. It includes examinations of the sacraments, Church discipline, excommunication and religious ritual, among other Christian phenomena. The dissertation follows many of these elements from their medieval Catholic roots through to their Reformed Protestant derivations in the latter part of the century, showing considerable links between the traditions. -

2734 VOL. VIII, No. 10 NEWSLETTER the JOURNAL of the LONDON NUMISMATIC CLUB HONORARY EDITOR Peter A

ISSN 0950 - 2734 VOL. VIII, No. 10 NEWSLETTER THE JOURNAL OF THE LONDON NUMISMATIC CLUB HONORARY EDITOR Peter A. Clayton EDITORIAL 3 CLUB TALKS From Gothic to Roman: Letter Forms on the Tudor Coinage, by Toni Sawyer 5 Scottish Mints, by Michael Anderson 23 Members' Own Evening 45 Mudlarking on the Thames, by Nigel Mills 50 Patriotics and Store Cards: The Tokens of the American 1 Civil War, by David Powell 64 London Coffee-house Tokens, by Robert Thompson 79 Some Thoughts on the Copies of the Coinage of Carausius and Allectus, by Hugh Williamson 86 Roman Coins: A Window on the Past, by Ian Franklin 93 AUCTION RESULTS, by Anthony Gilbert 102 BOOK REVIEWS 104 Coinage and Currency in London John Kent The Token Collectors Companion John Whitmore 2 EDITORIAL The Club, once again, has been fortunate in having a series of excellent speakers this past year, many of whom kindly supplied scripts for publication in the Club's Newsletter. This is not as straightforward as it may seems for the Editor still has to edit those scripts from the spoken to the written word, and then to type them all into the computer (unless, occasionally, a disc and a hard copy printout is supplied by the speaker). If contributors of reviews, notes, etc, could also supply their material on disc, it would be much appreciated and, not least, probably save a lot of errors in transmission. David Berry, our Speaker Finder, has provided a very varied menu for our ten meetings in the year (January and August being the months when there is no meeting). -

Traditions of King Duncan I Benjamin T

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 25 | Issue 1 Article 8 1990 From Senchus to histore: Traditions of King Duncan I Benjamin T. Hudson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hudson, Benjamin T. (1990) "From Senchus to histore: Traditions of King Duncan I," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 25: Iss. 1. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol25/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Benjamin T. Hudson From Senchus to histore: Traditions of King Duncan I The kings of Scotland prior to the reign of Malcolm III, popularly known as Malcolm Carunore (Malcolm "Bighead") have rarely been con sidered in connection with Scottish historical literature. Macbeth, largely due to Shakespeare's drama, has been the exception. For the medieval period alone, Nora Chadwick's examination of the Macbeth legend showed that a number of literary traditions, both native and foreign, can be detected in later medieval literature. 1 Macbeth was not alone in hav ing a variety of legends cluster about his memory; his historical and liter ary contemporary Duncan earned his share of legends too. This can be seen in a comparison of the accounts about Duncan preserved in historical literature, such as the Chroniea Gentis Seotorum of John of Fordun and the Original Chronicle of Scotland by Andrew of Wyntoun.2 Such a com- INora Chadwick, "The Story of Macbeth," Scottish Gaelic Studies (1949), 187-221; 7 (1951), 1-25.