The History and Poetry of the Scottish Borders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tweed Local Plan District Local Flood Risk Management Plan INTERIM REPORT

Tweed Local Flood Risk Management Plan 2016-2022: INTERIM REPORT Flood Risk Management (Scotland) Act 2009: Tweed Local Plan District Local Flood Risk Management Plan INTERIM REPORT Published by: Scottish Borders Council Lead Local Authority Tweed Local Plan District 01 March 2019 In partnership with: Tweed Local Flood Risk Management Plan 2016-2022: INTERIM REPORT Publication date: 1 March 2019 Terms and conditions Ownership: All intellectual property rights of the INTERIM REPORT Local Flood Risk Management Plan are owned by Scottish Borders Council, SEPA or its licensors. The INTERIM REPORT Local Flood Risk Management Plan cannot be used for or related to any commercial, business or other income generating purpose or activity, nor by value added resellers. You must not copy, assign, transfer, distribute, modify, create derived products or reverse engineer the INTERIM REPORT Local Flood Risk Management Plan in any way except where previously agreed with Scottish Borders Council or SEPA. Your use of the INTERIM REPORT Local Flood Risk Management Plan must not be detrimental to Scottish Borders Council or SEPA or other responsible authority, its activities or the environment. Warranties and Indemnities: All reasonable effort has been made to ensure that the INTERIM REPORT Local Flood Risk Management Plan is accurate for its intended purpose, no warranty is given by Scottish Borders Council or SEPA in this regard. Whilst all reasonable effort has been made to ensure that the INTERIM REPORT Local Flood Risk Management Plan are up to date, complete and accurate at the time of publication, no guarantee is given in this regard and ultimate responsibility lies with you to validate any information given. -

THE KINGS and QUEENS of BRITAIN, PART I (From Geoffrey of Monmouth’S Historia Regum Britanniae, Tr

THE KINGS AND QUEENS OF BRITAIN, PART I (from Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae, tr. Lewis Thorpe) See also Bill Cooper’s extended version (incorporating details given by Nennius’s history and old Welsh texts, and adding hypothesised dates for each monarch, as explained here). See also the various parallel versions of the Arthurian section. Aeneas │ Ascanius │ Silvius = Lavinia’s niece │ Corineus (in Cornwall) Brutus = Ignoge, dtr of Pandrasus │ ┌─────────────┴─┬───────────────┐ Gwendolen = Locrinus Kamber (in Wales) Albanactus (in Scotland) │ └Habren, by Estrildis Maddan ┌──┴──┐ Mempricius Malin │ Ebraucus │ 30 dtrs and 20 sons incl. Brutus Greenshield └Leil └Rud Hud Hudibras └Bladud │ Leir ┌────────────────┴┬──────────────┐ Goneril Regan Cordelia = Maglaurus of Albany = Henwinus of Cornwall = Aganippus of the Franks │ │ Marganus Cunedagius │ Rivallo ┌──┴──┐ Gurgustius (anon) │ │ Sisillius Jago │ Kimarcus │ Gorboduc = Judon ┌──┴──┐ Ferrex Porrex Cloten of Cornwall┐ Dunvallo Molmutius = Tonuuenna ┌──┴──┐ Belinus Brennius = dtr of Elsingius of Norway Gurguit Barbtruc┘ = dtr of Segnius of the Allobroges └Guithelin = Marcia Sisillius┘ ┌┴────┐ Kinarius Danius = Tanguesteaia Morvidus┘ ┌──────┬────┴─┬──────┬──────┐ Gorbonianus Archgallo Elidurus Ingenius Peredurus │ ┌──┴──┐ │ │ │ (anon) Marganus Enniaunus │ Idvallo Runo Gerennus Catellus┘ Millus┘ Porrex┘ Cherin┘ ┌─────┴─┬───────┐ Fulgenius Edadus Andragius Eliud┘ Cledaucus┘ Clotenus┘ Gurgintius┘ Merianus┘ Bledudo┘ Cap┘ Oenus┘ Sisillius┘ ┌──┴──┐ Bledgabred Archmail └Redon └Redechius -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Scots Pine Forest

Teacher information 1: The Scots Pine Forest What are native Caledonian pine forests? Native Caledonian pine forest contain Scots pine and a range of other trees, including junipers, birches, willows, and rowan and, in some areas, aspens. Many of the oldest trees in Scotland are found in native pinewoods. As the largest and longest lived tree in the Caledonian forest the Scots pine is a keystone species in the ecosystem, forming the backbone of which many other species depend. Scots pine trees over 200 years old are known as 'grannies', but they are young compared to one veteran pine in a remote part of Glen Loyne that was found to be over 550 years old. Native Caledonian pinewoods are more than just trees. They are home to a wide range of species that are found in similar habitat in Scandinavia and other parts of northern Europe and Russia. Despite this wide distribution, the Scots pine forests in Scotland are unique and distinct from those elsewhere because of the absence of any other native conifers. Native pinewoods have also provided a wide range of products that were used in everyday life in rural Scotland. Timber was used to build houses; berries, fungi and animals living in the pinewood provided food; and fir-candles were cut from the heart of old trees to provide early lighting. More recently, native pinewoods provided timber during the First and Second World Wars when imports to Britain were interrupted. How much native Caledonian pinewood is there in Britain? After the last Ice Age, Scotland’s ‘rainforest’ covered thousands of square kilometres in the Scottish Highlands. -

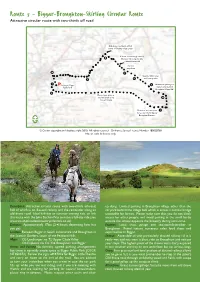

Biggar-Broughton-Skirling Circular Route Attractive Circular Route with Two-Thirds Off Road

Route 5 - Biggar-Broughton-Skirling Circular Route Attractive circular route with two-thirds off road Old drove road leads off NE corner of Skirling village green If drove road through trees is 8 blocked, ride along the side of the adjacent field Ford or jump burn 10 7 Beware rabbit holes 9 6 and loose ponies 1 PParking at Biggar 5 Alternative parking for Public Park trailers only behind Broughton Village Hall 2 Please leave gates as you find them along 4 disused railway Dismount and lead your 3 horse over the bridge by Broughton Brewery N © Crown copyright and database right 2010. All rights reserved. Ordnance Survey Licence Number 100020730 Not to scale. Indicative only. Description: Attractive circular route with two-thirds off-road, up dung. Limited parking in Broughton village other than the half of which is on disused railway and the remainder along an car park behind the village hall, which is across a narrow bridge old drove road. Ideal half-day or summer evening ride, or link unsuitable for lorries. Please make sure that you do not block this route with the John Buchan Way to make a full-day ride (see access for other people, and avoid parking in the small lay-by www.southofscotlandcountrysidetrails.co.uk). outside the school opposite the brewery during term-time. Distance: Approximately 17km (2-4 hours, depending how fast Facilities: Local shop, garage and tea-room/bistro/bar in you go). Broughton. Petrol station, numerous cafes, food shops and Location: Between Biggar in South Lanarkshire and Broughton in supermarket in Biggar. -

Nennius' Historia Brittonum

Nennius’ ‘Historia Brittonum’ Translated by Rev. W. Gunn & J. A. Giles For convenience, this text has been assembled and composed into this PDF document by Camelot On-line. Please visit us on-line at: http://www.heroofcamelot.com/ The Historia Brittonum Table of Contents Acknowledgements....................................................................................................................................4 Preface........................................................................................................................................................5 I. THE PROLOGUE..................................................................................................................................6 1.............................................................................................................................................................6 2.............................................................................................................................................................7 II. THE APOLOGY OF NENNIUS...........................................................................................................7 3.............................................................................................................................................................7 III. THE HISTORY ...................................................................................................................................8 4,5..........................................................................................................................................................8 -

LCSH Section W

W., D. (Fictitious character) William Kerr Scott Lake (N.C.) Waaddah Island (Wash.) USE D. W. (Fictitious character) William Kerr Scott Reservoir (N.C.) BT Islands—Washington (State) W.12 (Military aircraft) BT Reservoirs—North Carolina Waaddah Island (Wash.) USE Hansa Brandenburg W.12 (Military aircraft) W particles USE Waadah Island (Wash.) W.13 (Seaplane) USE W bosons Waag family USE Hansa Brandenburg W.13 (Seaplane) W-platform cars USE Waaga family W.29 (Military aircraft) USE General Motors W-cars Waag River (Slovakia) USE Hansa Brandenburg W.29 (Military aircraft) W. R. Holway Reservoir (Okla.) USE Váh River (Slovakia) W.A. Blount Building (Pensacola, Fla.) UF Chimney Rock Reservoir (Okla.) Waaga family (Not Subd Geog) UF Blount Building (Pensacola, Fla.) Holway Reservoir (Okla.) UF Vaaga family BT Office buildings—Florida BT Lakes—Oklahoma Waag family W Award Reservoirs—Oklahoma Waage family USE Prix W W. R. Motherwell Farmstead National Historic Park Waage family W.B. Umstead State Park (N.C.) (Sask.) USE Waaga family USE William B. Umstead State Park (N.C.) USE Motherwell Homestead National Historic Site Waahi, Lake (N.Z.) W bosons (Sask.) UF Lake Rotongaru (N.Z.) [QC793.5.B62-QC793.5.B629] W. R. Motherwell Stone House (Sask.) Lake Waahi (N.Z.) UF W particles UF Motherwell House (Sask.) Lake Wahi (N.Z.) BT Bosons Motherwell Stone House (Sask.) Rotongaru, Lake (N.Z.) W. Burling Cocks Memorial Race Course at Radnor BT Dwellings—Saskatchewan Wahi, Lake (N.Z.) Hunt (Malvern, Pa.) W.S. Payne Medical Arts Building (Pensacola, Fla.) BT Lakes—New Zealand UF Cocks Memorial Race Course at Radnor Hunt UF Medical Arts Building (Pensacola, Fla.) Waʻahila Ridge (Hawaii) (Malvern, Pa.) Payne Medical Arts Building (Pensacola, Fla.) BT Mountains—Hawaii BT Racetracks (Horse racing)—Pennsylvania BT Office buildings—Florida Waaihoek (KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa) W-cars W star algebras USE Waay Hoek (KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa : USE General Motors W-cars USE C*-algebras Farm) W. -

The Emergence of the Cumbrian Kingdom

The emergence and transformation of medieval Cumbria The Cumbrian kingdom is one of the more shadowy polities of early medieval northern Britain.1 Our understanding of the kingdom’s history is hampered by the patchiness of the source material, and the few texts that shed light on the region have proved difficult to interpret. A particular point of debate is the interpretation of the terms ‘Strathclyde’ and ‘Cumbria’, a matter that has periodically drawn comment since the 1960s. Some scholars propose that the terms were applied interchangeably to the same polity, which stretched from Clydesdale to the Lake District. Others argue that the terms applied to different territories: Strathclyde was focused on the Clyde Valley whereas Cumbria/Cumberland was located to the south of the Solway. The debate has significant implications for our understanding of the extent of the kingdom(s) of Strathclyde/Cumbria, which in turn affects our understanding of politics across tenth- and eleventh-century northern Britain. It is therefore worth revisiting the matter in this article, and I shall put forward an interpretation that escapes from the dichotomy that has influenced earlier scholarship. I shall argue that the polities known as ‘Strathclyde’ and ‘Cumbria’ were connected but not entirely synonymous: one evolved into the other. In my view, this terminological development was prompted by the expansion of the kingdom of Strathclyde beyond Clydesdale. This reassessment is timely because scholars have recently been considering the evolution of Cumbrian identity across a much longer time-period. In 1974 the counties of Cumberland and Westmorland were joined to Lancashire-North-of the-Sands and part of the West Riding of Yorkshire to create the larger county of Cumbria. -

Kingdom of Strathclyde from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Kingdom of Strathclyde From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Strathclyde (lit. "Strath of the Clyde"), originally Brythonic Ystrad Clud, was one of the early medieval kingdoms of the Kingdom of Strathclyde Celtic people called the Britons in the Hen Ogledd, the Teyrnas Ystrad Clut Brythonic-speaking parts of what is now southern Scotland and northern England. The kingdom developed during the ← 5th century–11th → post-Roman period. It is also known as Alt Clut, the Brythonic century name for Dumbarton Rock, the medieval capital of the region. It may have had its origins with the Damnonii people of Ptolemy's Geographia. The language of Strathclyde, and that of the Britons in surrounding areas under non-native rulership, is known as Cumbric, a dialect or language closely related to Old Welsh. Place-name and archaeological evidence points to some settlement by Norse or Norse–Gaels in the Viking Age, although to a lesser degree than in neighbouring Galloway. A small number of Anglian place-names show some limited settlement by incomers from Northumbria prior to the Norse settlement. Due to the series of language changes in the area, it is not possible to say whether any Goidelic settlement took place before Gaelic was introduced in the High Middle Ages. After the sack of Dumbarton Rock by a Viking army from Dublin in 870, the name Strathclyde comes into use, perhaps reflecting a move of the centre of the kingdom to Govan. In the same period, it was also referred to as Cumbria, and its inhabitants as Cumbrians. During the High Middle Ages, the area was conquered by the Kingdom of Alba, becoming part of The core of Strathclyde is the strath of the River Clyde. -

Aretha Franklin Soul '69 Mp3, Flac, Wma

Aretha Franklin Soul '69 mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Funk / Soul / Blues / Pop Album: Soul '69 Country: UK Released: 1969 Style: Rhythm & Blues, Soul MP3 version RAR size: 1484 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1496 mb WMA version RAR size: 1713 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 554 Other Formats: DXD MP3 MP1 APE RA DMF MMF Tracklist Hide Credits Ramblin' A1 3:07 Written-By – Maybelle Smith* Today I Sing The Blues A2 4:22 Written-By – Curtis Lewis River's Invitation A3 2:38 Written-By – Percy Mayfield Pitiful A4 3:01 Written-By – Charlie Singleton*, Rose Marie McCoy Crazy He Calls Me A5 3:24 Written-By – Bob Russell, Carl Sigman Bring It On Home To Me A6 3:39 Written-By – Sam Cooke Tracks Of My Tears B1 2:53 Written-By – Tarplin*, Robinson*, Moore* If You Gotta Make A Fool Of Somebody B2 3:06 Written-By – Rudy Clarke* Gentle On My Mind B3 2:26 Written-By – John Hartford So Long B4 4:33 Written-By – Melcher*, Harris*, Morgan* I'll Never Be Free B5 4:11 Written-By – Bernie Benjamin*, George Weiss* Elusive Butterfly B6 2:44 Written-By – Bob Lind Companies, etc. Recorded At – Atlantic Studios Manufactured By – Companhia Brasileira De Discos Credits Alto Saxophone – Frank Wess, George Dorsey Arranged By, Conductor – Arif Mardin Backing Vocals [Vocal Backgrounds] – Aretha Franklin, Evelyn Greene*, Wyline Ivy* Baritone Saxophone – Pepper Adams Bass – Jerry Jemmott (tracks: A2, B1), Ron Carter (tracks: A1, A3, A5, A6, B2, B6) Design [Album Design] – Loring Eutemey Drums – Bruno Carr (tracks: A1, A3, A5, A6, B2, B6), Grady Tate (tracks: B4, B5), -

Coastwise Sail

COflSTUJISE COASTWISE SAn. COASTWISE SAIL by JOHN ANDERSON Dedicated to the memory of the sailing ships of the West Country and the gallant seadogs who manned them. ' LONDON PERCIVAL MARSHALL & CO. LTD. , I FOREWORD O-DAY, the English sailing schooner is almost as dead as the dodo, and it is rather a doleful tale I T have to tell in these pages,-the story of the last days of sail in British waters. Twenty-five years ago or even less, our shores and our ports were literally alive with little sailing vessels engaged in our busy coasting trade, lovely sweet-lined topsail schooners, smart brigantines and stately barquentines; but old Father Time has dealt very hardly with them. What is the position to-day? Of all the great fleet that graced the British coasts in 1920, only two purely sailing vessels remain afloat in this year of grace 1947. These are the little topsail schooner Katie of Pad stow and the Irish three-masted topsail schooner Brook lands* of Cork. All the others have fallen by the way with the relentless passing of the years, or else they have been converted to cut-down auxiliary motor vessels, usually operating as motor ships rather than sailing vessels, and so the days of sail in the English coasting trade are "rapidly passing. No longer will one see a bunch of little schooners riding to their anchors in Falmouth Roads, and no longer will one see a fleet of wind-bound sailers sheltering off Holyhead. Yet these gallant little schooners of the West Country are not forgotten, and it is with the object of keeping their memory ever-green that this book is written. -

A Welsh Classical Dictionary

A WELSH CLASSICAL DICTIONARY DACHUN, saint of Bodmin. See s.n. Credan. He has been wrongly identified with an Irish saint Dagan in LBS II.281, 285. G.H.Doble seems to have been misled in the same way (The Saints of Cornwall, IV. 156). DAGAN or DANOG, abbot of Llancarfan. He appears as Danoc in one of the ‘Llancarfan Charters’ appended to the Life of St.Cadog (§62 in VSB p.130). Here he is a clerical witness with Sulien (presumably abbot) and king Morgan [ab Athrwys]. He appears as abbot of Llancarfan in five charters in the Book of Llandaf, where he is called Danoc abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 179c), and Dagan(us) abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 158, 175, 186b, 195). In these five charters he is contemporary with bishop Berthwyn and Ithel ap Morgan, king of Glywysing. He succeeded Sulien as abbot and was succeeded by Paul. See Trans.Cym., 1948 pp.291-2, (but ignore the dates), and compare Wendy Davies, LlCh p.55 where Danog and Dagan are distinguished. Wendy Davies dates the BLD charters c.A.D.722 to 740 (ibid., pp.102 - 114). DALLDAF ail CUNIN COF. (Legendary). He is included in the tale of ‘Culhwch and Olwen’ as one of the warriors of Arthur's Court: Dalldaf eil Kimin Cof (WM 460, RM 106). In a triad (TYP no.73) he is called Dalldaf eil Cunyn Cof, one of the ‘Three Peers’ of Arthur's Court. In another triad (TYP no.41) we are told that Fferlas (Grey Fetlock), the horse of Dalldaf eil Cunin Cof, was one of the ‘Three Lovers' Horses’ (or perhaps ‘Beloved Horses’).