Untitled, Undated Fragment of Newspaper Article Describes the Cellars One Hundred Years Later

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To the William Howard Taft Papers. Volume 1

THE L I 13 R A R Y 0 F CO 0.: G R 1 ~ ~ ~ • P R I ~ ~ I I) I ~ \J T ~' PAP E R ~ J N 1) E X ~ E R IE S INDEX TO THE William Howard Taft Papers LIBRARY OF CONGRESS • PRESIDENTS' PAPERS INDEX SERIES INDEX TO THE William Ho-ward Taft Papers VOLUME 1 INTRODUCTION AND PRESIDENTIAL PERIOD SUBJECT TITLES MANUSCRIPT DIVISION • REFERENCE DEPARTMENT LIBRARY OF CONGRESS WASHINGTON : 1972 Library of Congress 'Cataloging in Publication Data United States. Library of Congress. Manuscript Division. Index to the William Howard Taft papers. (Its Presidents' papers index series) 1. Taft, William Howard, Pres. U.S., 1857-1930. Manuscripts-Indexes. I. Title. II. Series. Z6616.T18U6 016.97391'2'0924 70-608096 ISBN 0-8444-0028-9 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price $24 per set. Sold in'sets only. Stock Number 3003-0010 Preface THIS INDEX to the William Howard Taft Papers is a direct result of the wish of the Congress and the President, as expressed by Public Law 85-147 approved August 16, 1957, and amended by Public Laws 87-263 approved September 21, 1961, and 88-299 approved April 27, 1964, to arrange, index, and microfilm the papers of the Presidents in the Library of Congress in order "to preserve their contents against destruction by war or other calamity," to make the Presidential Papers more "readily available for study and research," and to inspire informed patriotism. Presidents whose papers are in the Library are: George Washington James K. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NFS Form 10-900 . 10244018 (Rev. 8-86) United States Department of the Interior tj National Park Service uu National Register of Historic Places JUN 2 91990 Registration Form NATIONAL REGISTER This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for Individual properties or districts. See Instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each Item by marking "x" In the appropriate box or by entering the requested Information. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, styles, materials, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategorles listed In the Instructions. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-9QOa). Type all entries, 1. Name of Property^ ""*"" historic name jpringland 2, Location _3550 Tilden Street N.W, street & number Washington not for publleatlon N/A city, town .__* vicinity ~WI statepistrict of Columbia code D.C. county N/A code DC 001 Zipped* 200.1.6 3. Classification Ownership of Property Category of Property Number of Resources within Property X private " building(s) Contributing Noncontributing public-local c district 1 1 buildings public-State site .____ sites n public-Federal c structure ____ structures I I object ____ objects 1 1 Total Name of related multiple property listing: Number of contributing resources previously _________N/A___________ listed in the National Register 0 4. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this LE] nomination EU request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Rlaces and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

The INDIAN CHIEFS of PENNSYLVANIA by C

WENNAWOODS PUBLISHING Quality Reprints---Rare Books---Historical Artwork Dedicated to the preservation of books and artwork relating to 17th and 18th century life on America’s Eastern Frontier SPRING & SUMMER ’99 CATALOG #8 Dear Wennawoods Publishing Customers, We hope everyone will enjoy our Spring‘99 catalog. Four new titles are introduced in this catalog. The Lenape and Their Legends, the 11th title in our Great Pennsylvania Frontier Series, is a classic on Lenape or Delaware Indian history. Originally published in 1885 by Daniel Brinton, this numbered title is limited to 1,000 copies and contains the original translation of the Walum Olum, the Lenape’s ancient migration story. Anyone who is a student of Eastern Frontier history will need to own this scarce and hard to find book. Our second release is David Zeisberger’s History of the Indians of the Northern American Indians of Ohio, New York and Pennsylvania in 18th Century America. Seldom does a book come along that contains such an outstanding collection of notes on Eastern Frontier Indian history. Zeisberger, a missionary in the wilderness among the Indians of the East for over 60 years, gives us some of the most intimate details we know today. Two new titles in our paperback Pennsylvania History and Legends Series are: TE-A-O-GA: Annals of a Valley by Elsie Murray and Journal of Samuel Maclay by John F. Meginness; two excellent short stories about two vital areas of significance in Pennsylvania Indian history. Other books released in last 6 months are 1) 30,000 Miles With John Heckewelder or Travels Among the Indians of Pennsylvania, New York, Ohio in the 18th Century, 2) Early Western Journals, 3) A Pennsylvania Bison Hunt, and 4) Luke Swetland’s Captivity. -

Brief Genealogies of the Tyler, Taft, Wood, Bates

: v- ; %LERy TiS^WeODg^'^. :-:| ; - >¦ ¦ \;;;:S:-;f; ¦¦¦¦¦:'^hUM^i ANCESTORS OF NEWELL TJLER and! WIFE. ;c6MPILED .NEWELL TYLER—1 '¦ BY• • 88a. ,-< .-'7 m ¦ ' :: - : I«aj3s.: ;/ . , ;':i. Worcester, _"¦..." ~; Tyi.br |^r. Phinted by'' ' & No. 442 K£ain Strut. ; I '¦ V •¦' -: -' ";V8B'2. _ •.. COAT OF ARMS OF THE TYLER FAMILY ANDOVER BRANCH. — Translation of Motto For God, for Country, for Friends. InBx6b»nge -Amer. Ant. Soo. 25 Jl 190/ Brief History of the Tyler Families IN AMERICA. The Tylers are not numerous in England, though they have been there for several centuries. The name hast been traced inthe English records as far back as . The records published by the Brit ish Government are in several of our American^ Colleges, at Cambridge, Providence, Amherst, etc. There are six or seven immigrant families in the United States; those in Virginia and Maryland may be from one family, a question that cannot be settled at ihis late dayi William and Elizabeth Tyler arrived in Virginia in 1620, John and Thomas in 1635, al] from Lon don, England. Job Tyler came to Massachusetts in 1635, an(^ settled in Andover. Thomas Tyler came from Budleigh, Devonshire, England, and settled in Boston. William Tyler came from London in 1787, and settled in Boston. William Tyler came from Wiltshire, England, to New Jersey. , His descendants reside in Salem in that State. The name of the immigrant, Tyler, to Connecti cut cannot be ascertained. The late Rev. William Tyler of Auburndale, Mass., left a large manuscript record of the various 3 4 Tyler families, to which the compiler of this work is indebted for the foregoing sketches. -

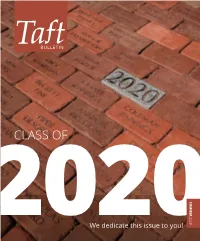

CLASS of SUMMER 2020 We Dedicate This Issue to You! SUMMER 2020

SUMMER 2020 We dedicate this issue to you! CLASS OF SUMMER 2020 INSIDE DEPARTMENTS 3 On Main Hall 12 Around the Pond Taft honored the Class of 32 In Print 2020 with a special online 56 Annual Fund Report Commencement tribute 59 Class Notes that included video well- AZIR/SHUTTERSTOCK.COM 102 wishes from faculty, the Milestones head of school, and alumni, as well as a photo montage of our graduating seniors. On MAIN HALL A WORD FROM HEAD Facing Complex Challenges OF SCHOOL WILLY MACMULLEN ’78 IT’S BEEN A SPRING LIKE NO OTHER, AND IT FEELS AS SUMMER 2020 ON THE COVER IF TAFT IS LODGED IN A MOMENT IN OUR NATION’S Volume 90, Number 3 We dedicate this issue to the HISTORY WHEN WE ARE FACING TWO MASSIVE AND Class of 2020, who prevailed EDITOR through months of remote learning, COMPLEX CHALLENGES—ONE OF THOSE HINGE Linda Hedman Beyus social distancing, and being away MOMENTS WHERE GREAT CHANGES ARE SWINGING from campus during the spring ON AN AXIS. THE FIRST IS THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC, DIRECTOR OF MARKETING AND COMMUNICATIONS months of the pandemic. The Kaitlin Thomas Orfitelli PERHAPS THE GREATEST HEALTH CHALLENGE WE HAVE CLASS OF tradition of honoring the newest KNOWN IN OVER A CENTURY. THE SECOND IS OUR class of graduates continues, with ASSISTANT DIRECTOR OF MARKETING AND COMMUNICATIONS bricks of each graduate’s name NATIONAL RECKONING WITH STRUCTURAL RACISM Debra Meyers placed on the school’s paths. SUMMER AND THE KILLING OF BLACK PEOPLE BY POLICE. THEY PHOTOGRAPHY 2020 ROBERT FALCETTI ARE DISTINCT AND YET CONNECTED, AND TAFT WILL BE We dedicate this issue to you! Robert Falcetti CHANGED BY BOTH. -

Wine List Intro.Docx

Supplement to Wine & Gastronomy Catalogues This book list, together with my Wine & Gastronomy Catalogues (1996-2002) represents, to the best of my reconstructive ability, the complete collection built over a roughly twenty-year period ending in 1982. The Wine & Gastronomy Catalogues had been drawn from books that suffered fire and water torture in 1979. The present list also includes books acquired before and after that event, while we were living in Italy, and before I reluctantly rejected the idea of rebuilding the collection. A few of these later acquisitions were offered for sale in the catalogues, but most of them remain in my possession. They are identified here with the note “[**++].” The following additional identifiers are used in this list: [**ici] – “incomplete cataloguing information” available – “short title” detail at best. All of these books were lost or discarded. [**sold] – books sold prior to the Wine & Gastronomy series, including from my Catalogue 1, issued March 1990. [**kept] – includes bibliographies, reference books, and books on coffee, tea and chocolate, and a few others which escaped inclusion in the catalogues. All items not otherwise identified were lost or discarded. The list includes a number of wine maps, but there were a few others for which there wasn’t enough information available to justify inclusion. To the list of wine bibliographies consulted for the Wine & Gastronomy catalogues, I would like to add the extensive German bibliography by Renate Schoene, first published in 1978 as Bibliographie zur Geschichte des Weines (Mannheim, 1976), followed by three supplements (1978, 1982, 1984), and the second edition (München, 1988). -

President Peary Wants No Honors by Police

21. SUGAR. 96 Degree U. S. WEATHER BUREAU, September Last 2i Hours' Rainfall, trace. ESTABLISHED JULY 2, 1858. Test Centrifugals 4.23V'ac. Per Ton, $34.70. Temperature, Max. 82; Min. 73. Weather, fair. 'r 88 Analysis Beets, Us. 8V'i Per Ton, $89.40. VOL. L., NO. 8462. HONOLULU, HAWAII TERRITORY, WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 22, 1909. PRICE FIVE CENTS. MEYER 1 IS COLONISTS HEBE AY YET FIHE LOOKS PRESIDENT By CHRISTMAS BIT QUEER STRONGER BE SOLD AS i CORPORATION TAX IS First Party of Immigrants Will Police Think Blaze in Harbor Sail From Europe Next v Saloon May Have Been Month. : DF OLD Incendiary. THE 1ST EQUITABLE Before Christmas the first installment The Harbor Saloon, on Queen street, of the Portuguese immigrants, got to- caught fire last night under circum- gether by Special Immigration Agent stances which point strongly to incen- A. J. Campbell, will arrive here. The Ordinance Sidetracked diarism. The police are not at all sat- Viscount Sone May Retire From Korea AH Thinks American Ships Board of Immigration has received ad- isfied with the look of things, and vices from Campbell that he has com- for Consideration Night Watchman Larsen has been plac- Should Be Models pleted negotiations for the chartering ed under arrest. He is now held at the Minnesota in Mourning Peary Wants of a ship, and that the vessel will sail police station on suspicion. for World. on or about October 15. Later. The Harbor lost its license some time No Honors Yet. This is taken to mean that Campbell ago, and since then has not been occu- has collected his first party of colonists, pied. -

Proposal for Local Historic Districts in Mendon

PROPOSAL FOR LOCAL HISTORIC DISTRICTS IN THE TOWN OF MENDON 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ITEM PAGE SUMMARY 3 INTRODUCTION 4 METHODOLOGY 5 SIGNIFICANCE 7 (a) Historical Relevance 8 (b) Taft Homestead District 12 (c) Current Relevance 13 BOUNDARY DESCRIPTION (S) 14 RECOMMENDATION FOR BY-LAW 15 BY-LAW 16 APPENDIX 1: Photographs 24 APPENDIX 2: Listed Structures in proposed Local Historic Districts 58 APPENDIX 3: Maps 61 2 SUMMARY In 2015 Mendon’s Historic Commission approached the Mendon Board of Selectmen to discuss initiating the process to establish a local historic district. In 2016 the Board of Selectmen subsequently appointed a study committee to investigate the feasibility and desire of establishing a local historic district in the Town. The Study Committee is comprised of the following participants: Michael Goddard, Historic Commission (Study Committee Chair) Lynne Roberts, Resident and Realtor Janice Muldoon-Moors, Resident Tom Merolli, Resident and Historic Commission Special thanks go to the following individuals and committees assisting with this study: Bill Ambrosino, Chair Mendon Planning Board Anne Mazar, Chair Mendon Community Preservation Committee Kim Newman, Town Administrator Mendon Board of Selectmen Mendon Historic Commission Lawney Tinio, Resident and former Study Committee member Christopher Skelly, Mass Historic Commission Richard Grady, Resident & Local Historian John Trainor, Resident & Local Historian Photography courtesy of Neil Larson 2002 The Committee recommends the Town vote to approve the establishment of two districts, The Mendon Center District and the Taft Homestead District. The proposed districts are comprised of a total of 50 structures. Our public hearing for is tentatively scheduled for 04/27/2017 with the town meeting vote targeted for our Annual Town Meeting 05/05/2017. -

The Family Bible Preservation Project Has Compiled a List of Family Bible Records Associated with Persons by the Following Surname

The Family Bible Preservation Project's - Family Bible Surname Index - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Page Forward to see each Bible entry THE FAMILY BIBLE PRESERVATION PROJECT HAS COMPILED A LIST OF FAMILY BIBLE RECORDS ASSOCIATED WITH PERSONS BY THE FOLLOWING SURNAME: TAFT Scroll Forward, page by page, to review each bible below. Also be sure and see the very last page to see other possible sources. For more information about the Project contact: EMAIL: [email protected] Or please visit the following web site: LINK: THE FAMILY BIBLE INDEX Copyright - The Family Bible Preservation Project The Family Bible Preservation Project's - Family Bible Surname Index - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Page Forward to see each Bible entry SURNAME: TAFT UNDER THIS SURNAME - A FAMILY BIBLE RECORD EXISTS ASSOCIATED WITH THE FOLLOWING FAMILY/PERSON: FAMILY OF: TAFT, ARCHIBALD (1804-XXXX) SPOUSE: LYDIA MARIA ROOD MORE INFORMATION CAN BE FOUND IN RELATION TO THIS BIBLE - AT THE FOLLOWING SOURCE: SOURCE: ONLINE INDEX: D.A.R. BIBLE RECORD DATABASE FILE/RECD: BIBLE DESCRIPTION: ARCHIBALD TAFT (BORN 1804) AND WIFE, LYDIA MARIA ROOD (BORN 1807) NOTE: - BOOK TITLE: NEW JERSEY DAR GRC REPORT ; S1 V337 : BIBLE RECORDS [BK. 2] / EAGLE ROCK CHAPTER THE FOLLOWING INTERNET HYPERLINKS CAN BE HELPFUL IN FINDING MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THIS FAMILY BIBLE: LINK: CLICK HERE TO ACCESS LINK LINK: CLICK HERE TO ACCESS LINK GROUP CODE: 02 Copyright - The Family Bible Preservation Project The Family Bible -

Ohio's First Ladies

From Frontierswoman to Flapper: Ohio’s First Ladies It is remarkable that Ohio is the home of seven First Ladies who were born or lived in the state. Their lives spanned from the colonial days of the United States to ushering in the Jazz Age of the 20th Century. Anna Harrison was born in New Jersey before the American Revolution, but her family settled in the Northwest Territory that became the state of Ohio. Anna’s Ohio was a wilderness, and she belongs to a class of rugged American women; the frontierswoman. The last two First Ladies were Florence Harding and Helen Taft. They were born in Ohio in 1860 and 1861 respectively. Their generation of women ushered in the Jazz Age, Prohibition and the Roaring 20s – the “new breed” of flappers with new opportunities for women. These seven women were unique and lively individuals, and their husbands had the good fortune to meet and marry them in Ohio. Anna Symmes Harrison (1775 – 1864) Anna Symmes was born in New Jersey on July 25, 1775. She was the second daughter born to John Cleves and Anna Symmes. Her widowed father served as a Continental Army Colonel during the American Revolution. He took both of his daughters to live with their maternal grandparents on Long Island, New York. Due to her family’s wealth and prestige, Anna was given an excellent education - rare for a girl at the time. Her education would serve her well for the life she was to lead as a frontierswoman, military wife and mother. Anna moved with her family to the Northwest Territory in 1794. -

Wigwam Hill & Mendon Town Forest

Page 1 of 60 This history is dedicated to the memory of Shirley Smith whose drive and commitment to the project has made the Town Forest, as it is today, possible. Early Years-Mendon is Born The town was incorporated in 1667 (2 dates are shown on the seal). In September 1662, after the deed was signed with the Native American chief, "Great John"* the pioneers entered this part of what is now southern Worcester County. An earlier, unofficial, settlement occurred here in the 1640s, by pioneers from Roxbury. In 1662, Squinshepauke Plantation was started at the Netmocke Settlement and Plantation or Netmocke Plantation as shown on the town’s seal. It was incorporated as the town of Mendon in 1667. It was named after the town of Mendham, Suffolk, England and bore that name until changed, intentionally or accidentally, by the General Court at the time of the town’s incorporation. The settlers were ambitious and set about clearing the roads that would mark settlement patterns throughout the town’s history. *Mendon still possesses this deed which is kept in a safe at the town hall. Page 2 of 60 The Mendon Town Forest Story A Google earth satellite map of the Town Forest shows the bulk of the heavily forested area and adjacent properties. It is located off Millville Road in the south-western corner of Mendon near the Millville & Uxbridge town lines. A neighboring property and popular tourist attraction is Southwick’s Zoo. The fire tower, indicated on the map, is the highest point on Wigwam Hill. -

Legislative Hearing Committee On

H.R. 37, H.R. 640 and H.R. 1000 LEGISLATIVE HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON NATIONAL PARKS, RECREATION, AND PUBLIC LANDS OF THE COMMITTEE ON RESOURCES U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION April 26, 2001 Serial No. 107-21 Printed for the use of the Committee on Resources ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.access.gpo.gov/congress/house or Committee address: http://resourcescommittee.house.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 71-929 PS WASHINGTON : 2002 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 15:32 Jan 11, 2002 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 71929.TXT HRESOUR1 PsN: HRESOUR1 COMMITTEE ON RESOURCES JAMES V. HANSEN, Utah, Chairman NICK J. RAHALL II, West Virginia, Ranking Democrat Member Don Young, Alaska, George Miller, California Vice Chairman Edward J. Markey, Massachusetts W.J. ‘‘Billy’’ Tauzin, Louisiana Dale E. Kildee, Michigan Jim Saxton, New Jersey Peter A. DeFazio, Oregon Elton Gallegly, California Eni F.H. Faleomavaega, American Samoa John J. Duncan, Jr., Tennessee Neil Abercrombie, Hawaii Joel Hefley, Colorado Solomon P. Ortiz, Texas Wayne T. Gilchrest, Maryland Frank Pallone, Jr., New Jersey Ken Calvert, California Calvin M. Dooley, California Scott McInnis, Colorado Robert A. Underwood, Guam Richard W. Pombo, California Adam Smith, Washington Barbara Cubin, Wyoming Donna M. Christensen, Virgin Islands George Radanovich, California Ron Kind, Wisconsin Walter B.