BASELINE COMMUNITY HEALTH DATA Alaska Pipeline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Helicopter-Supported Commercial Recreation Activities in Alaska

HELICOPTER-SUPPORTED COMMERCIAL RECREATION ACTIVITIES IN ALASKA Prepared for Alaska Quiet Rights Coalition Prepared by Nancy Welch Rodman, Welch & Associates and Robert Loeffler, Opus Consulting Funded by a grant from Alaska Conservation Foundation October 2006 Helicopter-Supported Commercial Recreation Activities in Alaska Helicopter-Supported Commercial Recreation Activities in Alaska TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary.................................................................................................................. ES-1 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................1-1 1.1. Purpose of this report...............................................................................................1-1 1.2. What is not covered by this report ...........................................................................1-1 2. Laws, Regulations and Policies..........................................................................................2-1 2.1. Legal Authority to Regulate.....................................................................................2-1 2.2. Strategies to Regulate Impacts.................................................................................2-5 2.3. Limitations on Authorities, Permit Terms, and Strategies.......................................2-7 2.4. Summary..................................................................................................................2-8 3. Types and Consumers of Helicopter-Supported -

(Asos) Implementation Plan

AUTOMATED SURFACE OBSERVING SYSTEM (ASOS) IMPLEMENTATION PLAN VAISALA CEILOMETER - CL31 November 14, 2008 U.S. Department of Commerce National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Weather Service / Office of Operational Systems/Observing Systems Branch National Weather Service / Office of Science and Technology/Development Branch Table of Contents Section Page Executive Summary............................................................................ iii 1.0 Introduction ............................................................................... 1 1.1 Background.......................................................................... 1 1.2 Purpose................................................................................. 2 1.3 Scope.................................................................................... 2 1.4 Applicable Documents......................................................... 2 1.5 Points of Contact.................................................................. 4 2.0 Pre-Operational Implementation Activities ............................ 6 3.0 Operational Implementation Planning Activities ................... 6 3.1 Planning/Decision Activities ............................................... 7 3.2 Logistic Support Activities .................................................. 11 3.3 Configuration Management (CM) Activities....................... 12 3.4 Operational Support Activities ............................................ 12 4.0 Operational Implementation (OI) Activities ......................... -

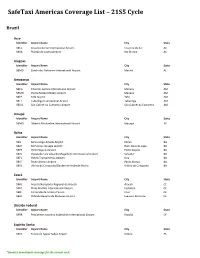

Safetaxi Americas Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle

SafeTaxi Americas Coverage List – 21S5 Cycle Brazil Acre Identifier Airport Name City State SBCZ Cruzeiro do Sul International Airport Cruzeiro do Sul AC SBRB Plácido de Castro Airport Rio Branco AC Alagoas Identifier Airport Name City State SBMO Zumbi dos Palmares International Airport Maceió AL Amazonas Identifier Airport Name City State SBEG Eduardo Gomes International Airport Manaus AM SBMN Ponta Pelada Military Airport Manaus AM SBTF Tefé Airport Tefé AM SBTT Tabatinga International Airport Tabatinga AM SBUA São Gabriel da Cachoeira Airport São Gabriel da Cachoeira AM Amapá Identifier Airport Name City State SBMQ Alberto Alcolumbre International Airport Macapá AP Bahia Identifier Airport Name City State SBIL Bahia-Jorge Amado Airport Ilhéus BA SBLP Bom Jesus da Lapa Airport Bom Jesus da Lapa BA SBPS Porto Seguro Airport Porto Seguro BA SBSV Deputado Luís Eduardo Magalhães International Airport Salvador BA SBTC Hotéis Transamérica Airport Una BA SBUF Paulo Afonso Airport Paulo Afonso BA SBVC Vitória da Conquista/Glauber de Andrade Rocha Vitória da Conquista BA Ceará Identifier Airport Name City State SBAC Aracati/Aeroporto Regional de Aracati Aracati CE SBFZ Pinto Martins International Airport Fortaleza CE SBJE Comandante Ariston Pessoa Cruz CE SBJU Orlando Bezerra de Menezes Airport Juazeiro do Norte CE Distrito Federal Identifier Airport Name City State SBBR Presidente Juscelino Kubitschek International Airport Brasília DF Espírito Santo Identifier Airport Name City State SBVT Eurico de Aguiar Salles Airport Vitória ES *Denotes -

Seward Historic Preservation Plan

City of Seward City Council Louis Bencardino - Mayor Margaret Anderson Marianna Keil David Crane Jerry King Darrell Deeter Bruce Siemenski Ronald A. Garzini, City Manager Seward Historic Preservation Commissioners Doug Capra Donna Kowalski Virginia Darling Faye Mulholland Jeanne Galvano Dan Seavey Glenn Hart Shannon Skibeness Mike Wiley Project Historian - Anne Castellina Community Development Department Kerry Martin, Director Rachel James - Planning Assistant Contracted assistance by: Margaret Branson Tim Sczawinski Madelyn Walker Funded by: The City of Seward and the Alaska Office of History and Archaeology Recommended by: Seward Historic Preservation Commission Resolution 96-02 Seward Planning and Zoning Commission Resolution 96-11 Adopted by: Seward City Council Resolution 96-133 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction......................................................................................................................................1 Purpose of the Plan ..............................................................................................................1 Method .................................................................................................................................2 Goals for Historic Preservation............................................................................................3 Community History and Character ..................................................................................................4 Community Resources...................................................................................................................20 -

FY22 Capital CC Meeting 9.Xlsx

CED Conference Committee Motion Sheet Department of Commerce, Community and Economic Development Capital Budget Indicates language H or S Indicates structure change Number Program Project Title House Fund Fund Position Senate Fund Fund Position Notes Version Change Code Source Change Change Code Source Change Adopted TOTAL 0.0 0 95,135.0 0 1 (Unassigned) Community Block Grants 6,000.0 1002 Fed Rcpts S 60.0 1003 GF/Match S 2 (Unassigned) National Petroleum Reserve - Alaska Impact Grant 9,100.0 1063 NPR Fund S Program 3 (Unassigned) AMCO Enforcement Case Management and 100.0 1004 Gen Fund S Investigations Report Writing System 100.0 1005 GF/Prgm S 4 (Unassigned) Alaska Energy Authority - Alaska Cargo and Cold 21,000.0 1002 Fed Rcpts S Storage 5 (Unassigned) Alaska Energy Authority - Alternative Energy and Energy 5,000.0 1002 Fed Rcpts S Efficiency Programs 6 (Unassigned) Alaska Energy Authority - Bulk Fuel Upgrades 7,500.0 1002 Fed Rcpts S 5,500.0 1140 AIDEA Div S 7 (Unassigned) Alaska Energy Authority - Rural Power Systems 12,500.0 1002 Fed Rcpts S Upgrades 5,000.0 1140 AIDEA Div S 8 (Unassigned) West Susitna Road Access 8,500.0 1002 Fed Rcpts S 9 Grants to Named Recipients (AS Inter-Island Ferry Authority 250.0 1004 Gen Fund S 37.05.316) CC Meeting 9 - 6/12/21 Page 1 CED Conference Committee Motion Sheet Department of Commerce, Community and Economic Development Capital Budget Indicates language H or S Indicates structure change Number Program Project Title House Fund Fund Position Senate Fund Fund Position Notes Version Change Code Source Change Change Code Source Change Adopted 10 Grants to Named Recipients (AS Matanuska-Susitna Borough- Arctic Winter Games 1,000.0 1004 Gen Fund CC: Modify to move from Grants to Named S 37.05.316) Recipeints to Grants to Municipalities. -

2030 Comprehensive Plan Seward, Alaska

2030 COMPREHENSIVE PLAN UPDATE VOLUME II CITY OF SEWARD Adopted: May 30, 2017 prepared by: PDC Engineers 2030 COMPREHENSIVE PLAN SEWARD, ALASKA Prepared For: The City of Seward, Alaska Prepared By: PDC Engineers Anchorage, Alaska Adopted By the City Council of the City of Seward May 30, 2017 by Resolution 2017-028 Adopted By the Kenai Peninsula Borough Assembly August 15, 2017 by Ordinance 2017-18 Introduced by: Mayor, Carpenter Date: 07/1 8/1 7 Hearing: 08/15/ 17 Action: Enacted as Amended Vote: 9 Yes, 0 No, 0 Absent KENAI PENINSULA BOROUGH ORDINANCE 2017-18 AN ORDINANCE AMENDING KPB 2.56.050 TO ADOPT VOLUMES I AND II OF THE SEWARD 2030 COMPREHENSIVE PLAN UPDATE AS THE OFFICIAL COMPREHENSIVE PLAN FOR THAT PORTION OF THE BOROUGH WITHIN THE BOUNDARIES OF THE CITY OF SEWARD WHEREAS, the Kenai Peninsula Borough provides for planning on an areawide basis in accordance with AS 29.40; and WHEREAS, m accordance with KPB 21.01.025(E), cities requesting extensive comprehensive plan amendments may recommend to the Kenai Peninsula Borough Planning Commission a change to the comprehensive plan; and WHEREAS, with the completion of Volumes I and II of the Seward 2030 Comprehensive Plan, the City of Seward has prepared extensive comprehensive plan amendments for that area of the borough within the boundaries of the City of Seward; and WHEREAS, over the last two years the City of Seward Planning and Zoning Commission has held thirteen ( 13) public work sessions and meetings working on the updates; and WHEREAS, throughout the update process, members of -

Alaska LNG, Docket No. PF14-21-000, Draft Resource Report

DOCKET NO. PF14-21-000 DRAFT RESOURCE REPORT NO. 5 SOCIOECONOMICS PUBLIC VERSION Document Number: USAKE-PT-SRREG-00-0005 DOCKET NO. PF14-21-000 DOC NO: USAI-EX-SRREG-00-0005 DRAFT RESOURCE REPORT NO. 5 DATE: FEBRUARY 2, 2015 ALASKA LNG SOCIOECONOMICS REVISION: 0 PROJECT PUBLIC VERSION SUMMARY OF FILING INFORMATION RESOURCE REPORT No. 5 SUMMARY OF FILING INFORMATION Filing Requirement Found in Section 1. For major aboveground facilities and major pipeline projects that require an EIS, describe 5.2 and 5.3 existing socioeconomic conditions within the project area. (18 C.F.R. § 380.12(g)(1)) 2. For major aboveground facilities, quantify impact on employment, housing, local government services, local tax revenues, transportation, and other relevant factors within 5.4 through 5.9 the project area. (18 C.F.R. § 380.12(g)(2-6)) Additional Information Often Missing and Resulting in Data Requests Evaluate the impact of any substantial immigration of people on governmental facilities 5.4 and services and describe plans to reduce the impact on local infrastructure. Describe on-site manpower requirements, including the number of construction personnel who currently reside within the impact area, would commute daily to the site from outside 5.4 the impact area, or would relocate temporarily within the impact area. Estimate total worker payroll and material purchases during construction and operation. 5.4 Determine whether existing housing within the impact area is sufficient to meet the needs 5.4 of the additional population. Describe the number and types of residences and businesses that would be displaced by the project, procedures to be used to acquire these properties and types and amounts of TBD relocation assistance payments. -

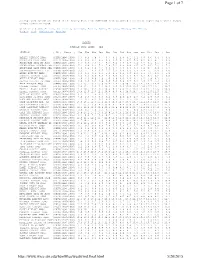

Page 1 of 7 5/20/2015

Page 1 of 7 Average wind speeds are based on the hourly data from 1996-2006 from automated stations at reporting airports (ASOS) unless otherwise noted. Click on a State: Arizona , California , Colorado , Hawaii , Idaho , Montana , Nevada , New Mexico , Oregon , Utah , Washington , Wyoming ALASKA AVERAGE WIND SPEED - MPH STATION | ID | Years | Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec | Ann AMBLER AIRPORT AWOS |PAFM|1996-2006| 6.7 8.5 7.9 7.7 6.7 5.3 4.8 5.1 6.1 6.8 6.6 6.4 | 6.5 ANAKTUVUK PASS AWOS |PAKP|1996-2006| 8.9 9.0 9.1 8.6 8.6 8.5 8.1 8.5 7.6 8.2 9.3 9.1 | 8.6 ANCHORAGE INTL AP ASOS |PANC|1996-2006| 6.7 6.0 7.5 7.7 8.7 8.2 7.8 6.8 7.1 6.6 6.1 6.1 | 7.1 ANCHORAGE-ELMENDORF AFB |PAED|1996-2006| 7.3 6.9 8.1 7.6 7.8 7.2 6.8 6.4 6.5 6.7 6.5 7.2 | 7.1 ANCHORAGE-LAKE HOOD SEA |PALH|1996-2006| 4.9 4.2 5.8 5.7 6.6 6.3 5.8 4.8 5.3 5.2 4.7 4.4 | 5.3 ANCHORAGE-MERRILL FLD |PAMR|1996-2006| 3.2 3.1 4.4 4.7 5.5 5.2 4.8 4.0 3.9 3.8 3.1 2.9 | 4.0 ANIAK AIRPORT AWOS |PANI|1996-2006| 4.9 6.6 6.5 6.4 5.6 4.5 4.2 4.0 4.6 5.5 5.5 4.1 | 5.1 ANNETTE AIRPORT ASOS |PANT|1996-2006| 9.2 8.2 8.9 7.8 7.4 7.0 6.2 6.4 7.2 8.3 8.6 9.8 | 8.0 ANVIK AIRPORT AWOS |PANV|1996-2006| 7.6 7.3 6.9 5.9 5.0 3.9 4.0 4.4 4.7 5.2 5.9 6.3 | 5.5 ARCTIC VILLAGE AP AWOS |PARC|1996-2006| 2.8 2.8 4.2 4.9 5.8 7.0 6.9 6.7 5.2 4.0 2.7 3.3 | 4.6 ATKA AIRPORT AWOS |PAAK|2000-2006| 15.1 15.1 13.1 15.0 13.4 12.4 11.9 10.7 13.5 14.5 14.7 14.4 | 13.7 BARROW AIRPORT ASOS |PABR|1996-2006| 12.2 13.1 12.4 12.1 12.4 11.5 12.6 12.5 12.6 14.0 13.7 13.1 | 12.7 BARTER ISLAND AIRPORT |PABA|1996-2006| -

Seward Alaska

2017 community services directory health, recreation & community organizations seward alaska Seward Prevention Coalition wellness | education | advocacy | support Table of Contents Emergency Services 1-3 Health Services 3-6 Community Resources 6-11 Community Service Organizations 11-12 Recreation 12-14 Education 14-16 Parent & Youth Resources 16-19 Fellowships 19-20 Tourism, Information & Media 21-22 Transportation & Housing 22-23 Alaska Resources 23-24 Facebook Listings 25 Emergency Services IN CASE OF EMERGENCY DIAL 911 LAW ENFORCEMENT Alaska State Troopers .............................................................. 224-3346 201 Third Avenue, Suite 202 Soldotna Dispatch ................................................................907-262-4453 www.dps.state.ak.us/ast Seward Police Department ...................................................... 224-3338 410 Adams Street / P.O. Box 167 www.cityofseward.us FIRE SERVICES Bear Creek Volunteer Fire & Emergency Medical Services 224-3345 13105 Seward Hwy, Mile 5.5 www.kpb.us/service-areas/bcfsa Moose Pass Volunteer Fire Co. 491-5776 Moose Pass, www.moosepassfire.com Seward Volunteer Fire Department 224-3445 316 Fourth Avenue, www.cityofseward.us MEDICAL SERVICES Providence Emergency Clinic 224-2846 417 First Avenue, P.O. Box 365 www.alaska.providence.org/locations/p/psmcc Seward Community Health Center ...... 224-2273 417 First Avenue, www.sewardhealthcenter.org Seward Volunteer Ambulance Corps ... 224-3987 200 D Street, P.O. Box 1136 www.sewardambulance.com 1 ANIMAL CONTROL Alaska SeaLife Center Rescue & Rehabilitation Hotline ......................................888-774-7325 Report stranded marine mammals and birds: www.alaskasealife.org/stranding_guidelines Pet Poison Helpline ...........................................................855-764-7661 www.petpoisonhelpline.com Seward Animal Shelter ............................................................ 224-7495 412 Sixth Avenue, P.O. Box 167 www.petfinder.com/shelters/AK10 Seward Animal Clinic ............................................................. -

Appendix H Draft Plan of Development

DOCKET NO. CP17-___-000 DOC NO: USAI-PE-SRREG-00- RESOURCE REPORT NO. 8 000008-000 ALASKA LNG APPENDIX H – DRAFT PLAN OF DATE: APRIL 14, 2017 PROJECT DEVELOPMENT REVISION: 0 PUBLIC APPENDIX H DRAFT PLAN OF DEVELOPMENT DRAFT PLAN OF DEVELOPMENT AKLNG-6020-REG-PLN-DOC-00029 AKLNG-6020-REG-PLN-DOC-00029 PLAN OF DEVELOPMENT 4-APR-17 REVISION: 0 PUBLIC PAGE 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................. 5 1.1 PROJECT OVERVIEW ............................................................................................................. 5 1.2 SUMMARY OF PROJECT REGULATORY FRAMEWORK ................................................................ 8 1.3 DOCUMENT ORGANIZATION AND REVISION .............................................................................. 8 2.0 PROJECT PURPOSE AND DESCRIPTION ................................................................................... 9 2.1 EXPECTED PUBLIC BENEFITS ............................................................................................... 10 2.2 PROJECT DESCRIPTION ....................................................................................................... 10 2.2.1 Overview .............................................................................................................. 10 2.3 COMMODITY AND PURPOSE ................................................................................................. 12 3.0 PROJECT LOCATION AND LAND REQUIREMENTS -

Chapter 3 2 Land Management Policies for Each Management Unit 3 4 Introduction

1 Chapter 3 2 Land Management Policies for Each Management Unit 3 4 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 1 5 Organization of Chapter ...................................................................................................... 2 6 Land Use Designations ....................................................................................................... 2 7 Map 3: Planning Area and Regions ............................................................................. 3 8 Designations Used in This Plan .......................................................................................... 5 9 Explanation of Habitat Designations .................................................................................. 9 10 Explanation of Oil and Gas Designation .......................................................................... 10 11 Resources and Uses and Management Intent .................................................................... 10 12 Duration and Flexibility of Plan ....................................................................................... 11 13 Glossary ............................................................................................................................ 12 14 Plan Structure .......................................................................................................................... 12 15 Plan Regions .................................................................................................................... -

2004-2006 STIP Phases

2004-2006 STIP National Highway System draft DRAFT STIP Req'd Funding >6 Need ID Highway Location Project Description/Funding Source Phse Apprn FFY 04 FFY 05 FFY 06 FFY 07 FFY 08 FFY 09FFY 10 years 10547 Alaska MP 1222 to 1235 Rehabilitation - (Border West) 2 500.0 410.0 Leveling and resurfacing. 4 9,000.0 Federal IM 0.0 0.0 467.0 382.9 8,406.0 0.0 State 0.0 0.0 33.0 27.1 594.0 0.0 Other Project Total 0.0 0.0 500.0 410.0 9,000.0 0.0 0.0 10548 Alaska MP 1256 to 1270 Rehab - Lakeview - Northway Jct. 2 560.0 Leveling and Resurfacing. 4 Federal IM 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 509.4 State 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 50.6 Other Project Total 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 560.0 7,000.0 6088 Alaska MP 1270 to 1314 Rehabilitation - Northway Junction to Tok 2 150.0 Relevel, resurface and install WIM - Northway Junction to Tok. 4 7,770.0 Federal IM 0.0 140.1 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 State 0.0 9.9 7,770.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Other Project Total 0.0 150.0 7,770.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 7367 Alaska MP 1308 - Tok Weigh Station 2 200.0 New weighing system facility to facilitate simultaneous axle group and gross weight indications for truck weight enforcement.