Alaska LNG, Docket No. PF14-21-000, Draft Resource Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KODY LOTNISK ICAO Niniejsze Zestawienie Zawiera 8372 Kody Lotnisk

KODY LOTNISK ICAO Niniejsze zestawienie zawiera 8372 kody lotnisk. Zestawienie uszeregowano: Kod ICAO = Nazwa portu lotniczego = Lokalizacja portu lotniczego AGAF=Afutara Airport=Afutara AGAR=Ulawa Airport=Arona, Ulawa Island AGAT=Uru Harbour=Atoifi, Malaita AGBA=Barakoma Airport=Barakoma AGBT=Batuna Airport=Batuna AGEV=Geva Airport=Geva AGGA=Auki Airport=Auki AGGB=Bellona/Anua Airport=Bellona/Anua AGGC=Choiseul Bay Airport=Choiseul Bay, Taro Island AGGD=Mbambanakira Airport=Mbambanakira AGGE=Balalae Airport=Shortland Island AGGF=Fera/Maringe Airport=Fera Island, Santa Isabel Island AGGG=Honiara FIR=Honiara, Guadalcanal AGGH=Honiara International Airport=Honiara, Guadalcanal AGGI=Babanakira Airport=Babanakira AGGJ=Avu Avu Airport=Avu Avu AGGK=Kirakira Airport=Kirakira AGGL=Santa Cruz/Graciosa Bay/Luova Airport=Santa Cruz/Graciosa Bay/Luova, Santa Cruz Island AGGM=Munda Airport=Munda, New Georgia Island AGGN=Nusatupe Airport=Gizo Island AGGO=Mono Airport=Mono Island AGGP=Marau Sound Airport=Marau Sound AGGQ=Ontong Java Airport=Ontong Java AGGR=Rennell/Tingoa Airport=Rennell/Tingoa, Rennell Island AGGS=Seghe Airport=Seghe AGGT=Santa Anna Airport=Santa Anna AGGU=Marau Airport=Marau AGGV=Suavanao Airport=Suavanao AGGY=Yandina Airport=Yandina AGIN=Isuna Heliport=Isuna AGKG=Kaghau Airport=Kaghau AGKU=Kukudu Airport=Kukudu AGOK=Gatokae Aerodrome=Gatokae AGRC=Ringi Cove Airport=Ringi Cove AGRM=Ramata Airport=Ramata ANYN=Nauru International Airport=Yaren (ICAO code formerly ANAU) AYBK=Buka Airport=Buka AYCH=Chimbu Airport=Kundiawa AYDU=Daru Airport=Daru -

Country IATA ICAO Airport Name Location Served 남극 남극 TNM SCRM Teniente R. Marsh Airport Villa Las Estrellas, Antarctica 남아메리카-남동부 아르헨티나 MDZ SAME Gov

Continent Country IATA ICAO Airport name Location served 남극 남극 TNM SCRM Teniente R. Marsh Airport Villa Las Estrellas, Antarctica 남아메리카-남동부 아르헨티나 MDZ SAME Gov. Francisco Gabrielli International Airport (El Plumerillo) Mendoza, Argentina 남아메리카-남동부 아르헨티나 FMA SARF Formosa International Airport (El Pucú Airport) Formosa, Argentina 남아메리카-남동부 아르헨티나 RSA SAZR Santa Rosa Airport Santa Rosa, Argentina 남아메리카-남동부 아르헨티나 COC SAAC Concordia Airport (Comodoro Pierrestegui Airport) Concordia, Entre Ríos, Argentina 남아메리카-남동부 아르헨티나 GHU SAAG Gualeguaychú Airport Gualeguaychú, Entre Ríos, Argentina 남아메리카-남동부 아르헨티나 JNI SAAJ Junín Airport Junín, Buenos Aires, Argentina 남아메리카-남동부 아르헨티나 MGI SAAK Martín García Island Airport Buenos Aires Province, Argentina 남아메리카-남동부 아르헨티나 PRA SAAP General Justo José de Urquiza Airport Paraná, Entre Ríos, Argentina 남아메리카-남동부 아르헨티나 ROS SAAR Rosario - Islas Malvinas International Airport Rosario, Argentina 남아메리카-남동부 아르헨티나 AEP SABE Jorge Newbery Airpark Buenos Aires, Argentina 남아메리카-남동부 아르헨티나 LCM SACC La Cumbre Airport La Cumbre, Córdoba, Argentina 남아메리카-남동부 아르헨티나 COR SACO Ingeniero Ambrosio L.V. Taravella International Airport (Pajas Blancas) Córdoba, Córdoba, Argentina 남아메리카-남동부 아르헨티나 DOT SADD Don Torcuato International Airport (closed) Buenos Aires, Argentina 남아메리카-남동부 아르헨티나 FDO SADF San Fernando Airport San Fernando, Buenos Aires, Argentina 남아메리카-남동부 아르헨티나 LPG SADL La Plata City International Airport La Plata, Buenos Aires, Argentina 남아메리카-남동부 아르헨티나 EZE SAEZ Ministro Pistarini International Airport Ezeiza (near Buenos Aires), Argentina 남아메리카-남동부 아르헨티나 HOS SAHC Chos Malal Airport (Oscar Reguera Airport) Chos Malal, Neuquén, Argentina 남아메리카-남동부 아르헨티나 GNR SAHR Dr. Arturo Umberto Illia Airport General Roca, Río Negro, Argentina 남아메리카-남동부 아르헨티나 APZ SAHZ Zapala Airport Zapala, Neuquén, Argentina 남아메리카-남동부 아르헨티나 LGS SAMM Comodoro D. -

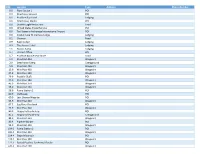

MM Location Type Address Phone Number 0.0 Flow Station 1 POI 0.0

MM Location Type Address Phone Number 0.0 Flow Station 1 POI 0.0 Deadhorse Airport POI 0.0 Prudhoe Bay Hotel Lodging 0.0 Deadhorse, Alaska POI 0.0 Double Eagle Restaurant Food 0.0 United States Postal Service POI 0.0 Ted Stevens Anchorage International Airport POI 0.0 Iniakuk Lake Wilderness Lodge Lodging 0.1 Chevron Food 0.9 Eagle Lodge Lodging 0.9 The Aurora Hotel Lodging 1.6 Brooks Camp Lodging 1.7 US Post Office POI 1.7 Prudhoe Bay General Store Food 1.9 Mile Post 414 Waypoint 2.9 Deadhorse Camp Campground 5.9 Mile Post 410 Waypoint 15.9 Mile Post 400 Waypoint 25.9 Mile Post 390 Waypoint 29.9 Franklin Bluffs POI 35.9 Mile Post 380 Waypoint 45.9 Mile Post 370 Waypoint 55.9 Mile Post 360 Waypoint 56.6 Pump Station 2 POI 60.9 Outhouse POI 60.9 Last Chance Wayside POI 65.9 Mile Post 350 Waypoint 67.7 Sag River Overlook POI 75.9 Mile Post 340 Waypoint 80.9 Happy Valley Airstrip POI 81.2 Happy Valley Airstrip Campground 85.9 Mile Post 330 Waypoint 89.4 Pipeline Border POI 95.9 Mile Post 320 Waypoint 104.6 Pump Station 3 POI 106.4 Mile Post 310 Waypoint 114.4 Slope Mountain POI 116.4 Mile Post 300 Waypoint 121.7 Buried Pipeline for Animal Border POI 126.4 Mile Post 290 Waypoint 126.7 Pipeline Border POI 131.6 Toolik Lake POI 131.6 Toolik Field Station POI 136.4 Mile Post 280 Waypoint 140.0 Summit: 3,074 ft Summit 141.1 Galbraith Campground Turnoff POI 141.5 Galbraith Lake Airport POI 142.1 Galbraith Lake POI 142.7 Galbraith Lake Campground Campground 145.0 Galbraith Bridge POI 146.4 Mile Post 270 Waypoint 147.3 Pump Station 4 POI 154.3 Raised -

BASELINE COMMUNITY HEALTH DATA Alaska Pipeline

Alaska Pipeline Project Baseline Community Health Data December, 2012 BASELINE COMMUNITY HEALTH DATA Alaska Pipeline Project December 2012 Prepared for the State of Alaska Health Impact Assessment Program Department of Health and Social Services Prepared by: NewFields Companies Alaska Pipeline Project Baseline Community Health Data December, 2012 NewFields Companies LLC State of Alaska HIA Program Printed Name: Scott Phillips, MD Printed Name: Paul J. Anderson, MD Title: Managing Partner Title: Program Manager Date Date: ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: With special thanks to the North Slope Borough Health Department for the use of their Baseline Community Health Analysis, Draft 2012, and the Alaska Native Epidemiology Center, Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium for the use of the data summaries and graphics in the Regional Health Profile for the Arctic Slope Region (April 2009), the Alaska Native Health Status Report (August 2009), and the Interior Regional Health Profile (2011). Alaska Pipeline Project Baseline Community Health Data December, 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW .............................................................................................1 1.1 OVERVIEW ....................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1.1 Organizing Baseline Health Data ............................................................................................... 1 2.0 PLACE AND PEOPLE .................................................................................................................3 -

Alaska Pipeline Project Resource Report No

Alaska Pipeline Project Resource Report No. 1 Preliminary Draft USAG-UR-SGREG-000002 ALASKA PIPELINE PROJECT USAG-UR-SGREG-000002 PRELIMINARY DRAFT RESOURCE REPORT 1 APRIL 2011 PAGE 1-I Introduction TransCanada Alaska Company, LLC and Foothills Pipe Lines, Ltd., working cooperatively with ExxonMobil, are collectively progressing the Alaska Pipeline Project1. The goal of APP is to treat, transport, and deliver gas from the North Slope of Alaska to markets in North America. This preliminary draft resource report pertains only to that portion of the Project in Alaska. Unless the context otherwise requires, references in the resource reports to APP refer only to the Alaska portion of the project. The pipelines, Gas Treatment Plant, and associated facilities described in this document are based on the estimated volumes of gas from projected customer commitments. If final volumes are significantly different, the design will be adjusted as needed. The location information, facility descriptions, resource impact data, construction methods, and mitigation measures presented in this report are preliminary and subject to change. APP is currently conducting engineering studies, environmental resource surveys, agency consultations, and stakeholder outreach efforts to further refine and define the details of the project. In particular, the route through the following areas is being more closely analyzed: • Alaska’s North Slope, including the Prudhoe Bay Unit Area; • The AtigunPass through the Brooks Range; • The Yukon River crossing; • The City of Fairbanks, including residential and commercial development, and proximity to Eielson Air Force Base; • The Delta Junction area, including waterbody crossings and residential development; • Multiple locations between Delta Junction and the Alaska-Yukon border, including fault crossings; and • The Upper Tanana region near Tetlin.