Langley, Cr (2017)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Communion Tokens of the Established Church of Scotland -Sixteenth, Seventeenth, and Eighteenth Centuries

V. COMMUNION TOKENS OF THE ESTABLISHED CHURCH OF SCOTLAND -SIXTEENTH, SEVENTEENTH, AND EIGHTEENTH CENTURIES. BY ALEXANDER J. S. BROOK, F.S.A. SCOT. o morn Ther s e familiawa e r objec Scotlann i t d fro e Reformatiomth n down to half a century ago than the Communion token, but its origin cannot be attributed to Scotland, nor was it a post-Reformation institution. e antiquitTh d universalitan y e toke th e unquestionable f ar no y . From very early times it is probable that a token, or something akin uses aln wa di l , toath-bounoit d secret societies. They will be found to have been used by the Greeks and Romans, whose tesserae were freely utilise r identifyinfo d gbeed ha thos no ewh initiated inte Eleusiniath o d othean n r kindred mysteries n thii d s an , s easilwa yy mannepavewa r thei e fo dth rr introduction e intth o Christian Church, where they wer e purposeth use r f excludinfo do e g the uninitiated and preventing the entrance of spies into the religious gatherings which were onl yselece opeth o tnt few. Afte persecutioe th r n cease whicho dt measurea n e i ,b y , ma thei e us r attributed, they would naturally continu e use b o distinguist do t e h between those who had a right to be present at meetings and those who had not. Tokens are unquestionably an old Catholic tradition, and their use Churce on t confiner countryy o no h an s o t wa d. -

Survey of Scottish Witchcraft Database Documentation and Description

1 Survey of Scottish Witchcraft Database Documentation and Description Contents of this Document I. Database Description (pp. 2-14) A. Description B. Database field types C. Miscellaneous database information D. Entity Models 1. Overview 2. Case attributes 3. Trial attributes II. List of tables and fields (pp. 15-29) III. Data Value Descriptions (pp. 30-41) IV. Database Provenance (pp. 42-54) A. Descriptions of sources used B. Full bibliography of primary, printed primary and secondary sources V. Methodology (pp. 55-58) VI. Appendices (pp. 59-78) A. Modernised/Standardised Last Names B. Modernised/Standardised First Names C. Parish List – all parishes in seventeenth century Scotland D. Burgh List – Royal burghs in 1707 E. Presbytery List – Presbyteries used in the database F. County List – Counties used in the database G. Copyright and citation protocol 2 Database Documents I. DATABASE DESCRIPTION A. DESCRIPTION (in text form) DESCRIPTION OF SURVEY OF SCOTTISH WITCHCRAFT DATABASE INTRODUCTION The following document is a description and guide to the layout and design of the ‘Survey of Scottish Witchcraft’ database. It is divided into two sections. In the first section appropriate terms and concepts are defined in order to afford accuracy and precision in the discussion of complicated relationships encompassed by the database. This includes relationships between accused witches and their accusers, different accused witches, people and prosecutorial processes, and cultural elements of witchcraft belief and the processes through which they were documented. The second section is a general description of how the database is organised. Please see the document ‘Description of Database Fields’ for a full discussion of every field in the database, including its meaning, use and relationships to other fields and/or tables. -

Scottish Witchcraft Survey Database Documentation and Description File

1 Survey of Scottish Witchcraft Database Documentation and Description Contents of this Document I. Database Description (pp. 2-14) A. Description B. Database field types C. Miscellaneous database information D. Entity Models 1. Overview 2. Case attributes 3. Trial attributes II. List of tables and fields (pp. 15-29) III. Data Value Descriptions (pp. 30-41) IV. Database Provenance (pp. 42-54) A. Descriptions of sources used B. Full bibliography of primary, printed primary and secondary sources V. Methodology (pp. 55-58) VI. Appendices (pp. 59-78) A. Modernised/Standardised Last Names B. Modernised/Standardised First Names C. Parish List – all parishes in seventeenth century Scotland D. Burgh List – Royal burghs in 1707 E. Presbytery List – Presbyteries used in the database F. County List – Counties used in the database G. Copyright and citation protocol 2 Database Documents I. DATABASE DESCRIPTION A. DESCRIPTION (in text form) DESCRIPTION OF SURVEY OF SCOTTISH WITCHCRAFT DATABASE INTRODUCTION The following document is a description and guide to the layout and design of the ‘Survey of Scottish Witchcraft’ database. It is divided into two sections. In the first section appropriate terms and concepts are defined in order to afford accuracy and precision in the discussion of complicated relationships encompassed by the database. This includes relationships between accused witches and their accusers, different accused witches, people and prosecutorial processes, and cultural elements of witchcraft belief and the processes through which they were documented. The second section is a general description of how the database is organised. Please see the document ‘Description of Database Fields’ for a full discussion of every field in the database, including its meaning, use and relationships to other fields and/or tables. -

D Unpender N E W S

Dunpender Community Council D UNPENDER N E W S The newsleer of Dunpender Community Council Autumn 2015 Gala Day 2015 Gala Day on 13 June was a great from Despicable Me. The Pretty but to name a few the committee success. It stayed dry and calm Mudders also managed a bit would particularly like to thank and the turnout from the village more walking after their morning those who placed an advert in the was excellent. This year’s parade exertions. Queen Lorel, her Con- programme, donated prizes, sup- was much larger than usual and sort Oliver and her court per- plied beer (Crown & Kitchen), many thanks are due to the driv- formed the traditional ceremony burgers (Linton Butchers), ice ers of the old cars that added beautifully, with the new Queen cream (Ian’s Confectionery), flow- considerable length to the parade being crowned by former Gala ers (Ruth from Sweetpeas, Marc’s and of course to the superb floats Queen Katie Bath, confirming Lo- and Stewart Stenhouse) ice to that embraced this year’s ‘Films’ rel as East Linton’s new Gala cool the drinks and rolls for the theme with Harry Potter (Beavers, Queen for the coming year. On a burgers (Co-op) and those who Cubs and Scouts), Paddington practical note, the new Gala Com- carefully checked the accounts (Rainbows and Brownies), 101 mittee not only ensured Gala (Dicksons). It was a delight to see Dalmations (Playgroup) all repre- Week went ahead as always but East Linton Gala supported by so sented in addition to the tradition- that its events were well attended many residents, making it a truly al Queen’s Float. -

University of Bradford Ethesis

Over the ditch and far away. Investigating Broxmouth and the landscape of South-East Scotland during the later prehistoric period. Item Type Thesis Authors Reader, Rachael Rights <a rel="license" href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/3.0/"><img alt="Creative Commons License" style="border-width:0" src="http://i.creativecommons.org/l/by- nc-nd/3.0/88x31.png" /></a><br />The University of Bradford theses are licenced under a <a rel="license" href="http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/">Creative Commons Licence</a>. Download date 01/10/2021 01:57:24 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10454/7347 University of Bradford eThesis This thesis is hosted in Bradford Scholars – The University of Bradford Open Access repository. Visit the repository for full metadata or to contact the repository team. Reader R (2012) Over the ditch and far away: Investigating Broxmouth and the landscape of South-East Scotland during the later prehistoric period. PhD Thesis. University of Bradford. © University of Bradford. This work is licenced for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence. Unique_N Name Parish NMRS_Number 1 Bara 1 Garvald and Bara NT56NE 90 2 Bara 2 Garvald and Bara NT57SE 149 3 Bara 3 Garvald and Bara NT57SE 92 4 Bara Wood Garvald and Bara NT56NE 23 5 Beanston 1 Prestonkirk NT57NW 107 6 Beanston 2 Prestonkirk NT57NE 98 7 Beanston Mains 1 Prestonkirk NT57NE 96 8 Beanston Mains 2 Prestonkirk NT57NE 97 9 Bell Craig Spott NT67SE 14 10 Belton Brae Dunbar NT67NW 58 11 Birks Plantation Whittingehame NT67SW 101 12 Black Castle Garvald -

War Memorial

Whitekirk War Memorial A search to identify the men named on the war memorial in St Mary’s Churchyard Whitekirk Whitekirk History Group February 2014 Introduction In September 1920, an unveiling and All sectors of society suffered losses in the dedication ceremony was held in the war, from Lord George Binning, heir to the graveyard of St Mary’s Church, Whitekirk, Earl of Haddington, to ploughmen, for the newly erected war memorial. labourers and foresters. Nearly half of those Designed by the architect Sir Robert who lost their lives were aged 20 or Lorimer, and built of stone from the younger. Doddington Quarry, the memorial listed the names of men from the parish of All of the fallen had enlisted in the army, Whitekirk and Tyninghame who had fallen although one later transferred to the Royal in service of their country during the First Flying Corps. Two served in overseas World War. regiments, having emigrated to Canada and to New Zealand prior to the outbreak of Two years earlier, Mr James Dow Stewart, war, where they enlisted in the forces of headmaster of the village school, had those countries. Four families lost two sons, prepared a hand drawn Roll of Honour while the Thomson family from Lochhouses listing the one hundred and thirty-seven was celebrated in the local press for having men of the parish who had served their six sons serving at the same time. country during the war. With twenty-nine men named on the war memorial and a The longest serving was James Nelson, who further three missing in action named on enlisted in September 1914. -

Agricultural Parishes 874

886 SEERAD Agricultural Parishes 874 880 891 870 878 Parish Code Parish Name Parish Code Parish Name Parish Code Parish Name Parish Code Parish Name Parish Code Parish Name Parish Code Parish Name Parish Code Parish Name Parish Code Parish Name Parish Code Parish Name 889 879 1 Aberdeen 38 Aboyne and Glentanar 75 Gartly 112 Fern 149 Killarow and Kilmeny 186 Mauchline 223 Ordiquhill 260 Langton 297 Dornock 2 Belhelvie 39 Birse 76 Glass 113 Glenisla 150 Kilchoman 187 Muirkirk 224 Alvah 261 Longformacus 298 Caerlaverock 877 3 Drumoak 40 Cluny 77 Huntly 114 Kingoldrum 151 Kildalton and Oa 188 New Cumnock 225 Banff 262 Polwarth 299 Dalton 888 882 4 Dyce 41 Coull 78 Rhynie 115 Kirriemuir 152 Campbeltown 189 Ochiltree 226 Boyndie 263 Swinton 300 Dumfries 885 5 Echt 42 Crathie and Braemar 79 Auchterless 116 Lintrathen 153 Gigha and Cara 190 Old Cumnock 227 Gamrie 264 Whitsome 301 Lochmaben 887 881 6 Fintray 43 Glenmuick Tullich & Glengairn 80 Fyvie 117 Ruthven 154 Kilcalmonell 191 Sorn 228 Rathven 265 Channelkirk 302 Mouswald 884 7 Kinellar 44 Kincardine O'Neil 81 King Edward 118 Tannadice 155 Killean and Kilchenzie 192 Stair 229 Cullen 266 Earlston 303 Ruthwell 883 8 Newhills 45 Logie Coldstone 82 Monquhitter 119 Auchterhouse 156 Saddell and Skipness 193 Ballantrae 230 Deskford 267 Gordon 304 Torthorwald 83 Turriff 157 Southend 194 Barr 268 Hume 305 Holywood 869 9 New Machar 46 Lumphanan 120 Dundee 231 Fordyce 890 10 Old Machar 47 Midmar 84 Brechin 121 Fowlis Easter 158 Craignish 195 Colmonell 232 Aberlour 269 Lauder 306 Kirkmahoe 11 Peterculter -

Listed Boxes June 2020

id name statutory_address location country county county_code historic_county_code district locality locality_code grade source source_current_id source_legacy_id listed lat lon 200351684 Rhynd Village, K3 Telephone Kiosk Rhynd Scotland Perth and Kinross S12000024 PRT Perth and Kinross Rhynd S13003071 A sc 351684 LB17718 11/10/1989 56.365295 -3.364286 200355822 Hazlehead Park, K6 Telephone Kiosk Aberdeen Scotland Aberdeen City S12000033 ABN Aberdeen City Aberdeen S13002844 B sc 355822 LB20670 23/06/1989 57.140121 -2.173955 200345974 Auchenblae High Street, K6 Telephone Kiosk Fordoun Scotland Aberdeenshire S12000034 KNC Aberdeenshire Fordoun S13002866 B sc 345974 LB13002 18/06/1992 56.899669 -2.450264 200356007 Broomhill Road, K6 Telephone Kiosk Aberdeen Scotland Aberdeenshire S12000034 ABN Aberdeenshire Aberdeen S13002845 B sc 356007 LB20825 15/12/1992 57.128291 -2.128195 200333965 Crathie, K6 Telephone Kiosk at Crathie Parish Church Crathie and Braemar Scotland Aberdeenshire S12000034 ABN Aberdeenshire Crathie And Braemar S13002862 B sc 333965 LB2991 23/06/1989 57.039976 -3.214547 200357309 High Street, K6 Telephone Kiosk Adjacent to Diack's Shop Banchory Scotland Aberdeenshire S12000034 KNC Aberdeenshire Banchory S13002863 B sc 357309 LB21873 18/06/1992 57.051343 -2.502458 200337997 Johnshaven, Main Street and Station Brae, K6 Telephone Kiosk Benholm Scotland Aberdeenshire S12000034 KNC Aberdeenshire Benholm S13002866 B sc 337997 LB6419 18/06/1992 56.794559 -2.336976 200353211 Luthermuir, Main Street, K6 Telephone Kiosk Marykirk Scotland -

Torness Nuclear Power Station Off-Site Emergency Plan: Outline Planning Zone (OPZ)

Torness Nuclear Power Station Off-Site Emergency Plan: Outline Planning Zone (OPZ) Torness Nuclear Power Station Outline Planning Zone Plan (OPZ) Prepared by East Lothian Council1 Great Britain has well developed emergency response arrangements and there is no change in radiological risk, which remains extremely low. Great Britain has benefitted from over 60 years of clean and safe nuclear power. REPPIR 2019, updated legislation in 2019, and along with other changes introduced Outline Planning Zones (OPZ), to plan for less likely but more severe emergencies, including unforeseen events. For civil nuclear sites, like Torness Nuclear Power Station, the OPZ has been pre-set at 30km, by regulation 9(1)(a) and schedule 5 of REPPIR-19. OPZ planning is lighter touch than for Detailed Emergency Planning Zones (DEPZ), and does not require capabilities to be in place ready to deploy as is the case for the DEPZ. This plan is an overview of the area between the 3km DEPZ and the boundary of the 30km OPZ, detailing the population in this area and in particular the most vulnerable. This plan further improves the already significant emergency response planning in place for Torness Nuclear Power Station. This plan should be read in conjunction with the East Lothian Council (ELC), Torness Nuclear Emergency Response plan which describes the detailed arrangements made for responding to off-site nuclear emergencies. This plan can be found on Resilience Direct and for public consumption on the ELC website with hard copies available at local libraries. 1 Any changes to this plan should be sent to [email protected] 1 Version 1.0 Torness OPZ plan released 2nd November 2020. -

New Series, Volume 9, 2008

NEW SERIES, VOLUME 9, 2008 DISCOVERY AND EXCAVATION IN SCOTLAND A’ LORG AGUS A’ CLADHACH AN ALBAINN NEW SERIES, VOLUME 9 2008 Editor Paula Milburn Archaeology Scotland Archaeology Scotland Archaeology Scotland is a voluntary membership organisation, which works to secure the archaeological heritage of Scotland for its people through education, promotion and support: t education, both formal and informal, concerning Scotland’s archaeological heritage t promotion of the conservation, management, understanding and enjoyment of, and access to, Scotland’s archaeological heritage t support through the provision of advice, guidance, resources and information related to archaeology in Scotland. Our vision Archaeology Scotland is a key centre of knowledge and expertise for Scottish archaeology, providing support and education for those interested and involved in archaeology, and promoting Scotland’s archaeological heritage for the benefit of all. Membership of Archaeology Scotland Membership is open to all individuals, local societies and organisations with an interest in Scottish archaeology. Membership benefits and services include access to a network of archaeological information on Scotland and the UK, four newsletters a year, the annual edition of the journal Discovery and excavation in Scotland, and the opportunity to attend Archaeology Scotland’s annual Summer School and the Archaeological Research in Progress conference. Further information and an application form may be obtained from Archaeology Scotland: Email [email protected] Website www.archaeologyscotland.org.uk. A’ lorg agus a’ cladhach an Albainn, the Gaelic translation of Discovery and excavation in Scotland, was supplied by Margaret MacIver, Lecturer in Gaelic & Education, and Professor Colm O’Boyle, Emeritus Professor, both at the Celtic, School of Language and Literature, University of Aberdeen. -

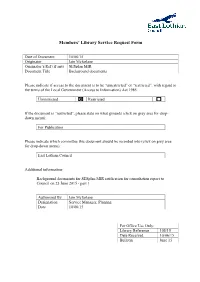

Members' Library Service Request Form

Members’ Library Service Request Form Date of Document 10/06/15 Originator Iain Mcfarlane Originator’s Ref (if any) SESplan MIR Document Title Background documents Please indicate if access to the document is to be “unrestricted” or “restricted”, with regard to the terms of the Local Government (Access to Information) Act 1985. Unrestricted Restricted If the document is “restricted”, please state on what grounds (click on grey area for drop- down menu): For Publication Please indicate which committee this document should be recorded into (click on grey area for drop-down menu): East Lothian Council Additional information: Background documents for SESplan MIR ratification for consultation report to Council on 23 June 2015 - part 1 Authorised By Iain Mcfarlane Designation Service Manager, Plannng Date 10/06/15 For Office Use Only: Library Reference 105/15 Date Received 10/06/15 Bulletin June 15 SESplan Spatial Strategy - Technical Note SESplan Spatial Strategy - Technical Note Contents 1 Background and Context 3 2 The SDP and Climate Change 4 3 The SDP and Placemaking 7 4 The Green Belt 10 5 The SESplan Audit 13 6 Considerations for MIR2 74 Appendices 1 Strategic Flood Risk Assessment 85 2 Accessibility Analysis 116 Spatial Strategy - Technical Note SESplan 3 Background and Context 1 1 Background and Context 1.1 This is one of a series of Technical Notes, prepared to provide background evidence in support of the second SESplan Main Issues Report (MIR2). This Technical Note sets out the methodology for identifying the options for the spatial strategy across Edinburgh and South East Scotland over the period to 2037. -

Local Development Plan2016

proposed local development plan 2016 draft environmental report CONTENTS NON-TECHNICAL SUMMARY 1 INTRODUCTION & BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 The Need for Strategic Environmental Assessment ............................................................................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 The Development Planning Regime .................................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 1.3 The Process for Preparing the LDP ...................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 1.4 Form & Content of the LDP ............................................................................................................................................................................................................... 11 1.5 The Key Facts Relating to the LDP ..................................................................................................................................................................................................... 13 1.6 SEA Activities to Date .......................................................................................................................................................................................................................