Download PDF Version

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teaching Standards- Based Creativity in the Arts

Teaching Standards-based Creativity in the Arts Issued by Office of Academic Standards South Carolina Department of Education Jim Rex State Superintendent of Education 2007 1 Table of Contents CONTRIBUTORS ................................................................................. 3 WHY CREATIVITY? ............................................................................. 5 CULTIVATING CREATIVITY IN ARTS EDUCATION: MYTHS, MISCONCEPTIONS, AND PRACTICAL PROCEDURES………………………..7 DANCE: .......................................................................................... 100 GRADES PREK-K ............................................................................... 101 GRADES 1-2 .................................................................................... 111 GRADES 3-5 .................................................................................... 122 GRADES 6-8 .................................................................................... 139 GRADES 9-12 .................................................................................. 162 GRADES 9-12 ADVANCED .................................................................... 186 DANCE CREATIVITY RESOURCE LIST ........................................................ 208 MUSIC ............................................................................................ 213 MUSIC: GENERAL ............................................................................. 214 GRADES PREK-K .............................................................................. -

NEO-Orientalisms UGLY WOMEN and the PARISIAN

NEO-ORIENTALISMs UGLY WOMEN AND THE PARISIAN AVANT-GARDE, 1905 - 1908 By ELIZABETH GAIL KIRK B.F.A., University of Manitoba, 1982 B.A., University of Manitoba, 1983 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of Fine Arts) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA . October 1988 <£> Elizabeth Gail Kirk, 1988 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Fine Arts The University of British Columbia 1956 Main Mall Vancouver, Canada V6T 1Y3 Date October, 1988 DE-6(3/81) ABSTRACT The Neo-Orientalism of Matisse's The Blue Nude (Souvenir of Biskra), and Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, both of 1907, exists in the similarity of the extreme distortion of the female form and defines the different meanings attached to these "ugly" women relative to distinctive notions of erotic and exotic imagery. To understand Neo-Orientalism, that is, 19th century Orientalist concepts which were filtered through Primitivism in the 20th century, the racial, sexual and class antagonisms of the period, which not only influenced attitudes towards erotic and exotic imagery, but also defined and categorized humanity, must be considered in their historical context. -

Guide to the Michigan Dance Archives: Harriet Berg Papers UP001608

Guide to the Michigan Dance Archives: Harriet Berg Papers UP001608 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on June 11, 2018. English Describing Archives: A Content Standard Walter P. Reuther Library 5401 Cass Avenue Detroit, MI 48202 URL: https://reuther.wayne.edu Guide to the Michigan Dance Archives: Harriet Berg Papers UP001608 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 History ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement ................................................................................................................................................... 6 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 6 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 7 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 7 Collection Inventory ...................................................................................................................................... -

The Experience Theater Choreographed by Pina Bausch

Revista Brasileira de Estudos da Presença ISSN: 2237-2660 Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul Pereira, Sayonara O Teatro da Experiência coreografado por Pina Bausch Revista Brasileira de Estudos da Presença, vol. 8, núm. 3, 2018, Julho-Setembro, pp. 487-521 Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul DOI: 10.1590/2237-266076215 Disponível em: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=463556259005 Como citar este artigo Número completo Sistema de Informação Científica Redalyc Mais informações do artigo Rede de Revistas Científicas da América Latina e do Caribe, Espanha e Portugal Site da revista em redalyc.org Sem fins lucrativos acadêmica projeto, desenvolvido no âmbito da iniciativa acesso aberto E‐ISSN 2237‐2660 The Experience Theater choreographed by Pina Bausch Sayonara Pereira Universidade de São Paulo – USP, São Paulo/SP, Brazil ABSTRACT – The Experience Theater choreographed by Pina Bausch – A theater where the spectator is involved in all senses, offering welcoming conditions. In the work of Pina Bausch, everyday body behavior is not just a matter of style; her dance develops content with a proper writing, inviting the spectator to experience a poetic reality. For this purpose, the article initially presents a historical line of Tanztheater, its attributes and interrelationships, closing with the specific characteristics of four works of the choreographer, created in the period comprising the initial two decades (1974-1989) of her fruitful production, and which were watched live by the author of the text. Keywords: Tanztheater. Pina Bausch. Experience Theater. Choreographies. RÉSUMÉ – Le Théâtre de l’Expérience chorégraphié par Pina Bausch – Un théâtre où le spectateur est impliqué dans tous vos sens, en offrant des conditions d’accueil. -

"The Dance of the Future"

Chap 1 Isadora Duncan THE DANCER OF THE FUTURE I HE MOVEMENT OF WAVES, of winds, of the earth is ever in the T same lasting harmony. V·le do not stand on the beach and inquire of th€ E>t:ea:n what was its movement in the past and what will be its movement in the future. We realize that the movement peculiar to its nature is eternal to its nature. The movement of the free animals and birds remains always in correspondence to their nature, the necessities and wants of that nature, and its correspond ence to the earth nature. It is only when you put free animals under ~~restr iction s that the"y lose the power-or moving lnlla rr'n o~y with nature, and adopt a movement expressive of the restncflons placed about thel!l. · . ------~- ,. So it has been with civili zed man. The movements of the savage, who lived in freedom in constant touch with Nature, were unrestricted, natural and beautiful. Only the movements of the r:ilkeJ..J22.9.y_ca~ be p:rfectl): 12_a~al. Man, arrived at the end of civilization, will have to return to nakedness, not to tl1e uncon scious nakedness of the savage, but to the conscious and acknow ledged nakedness of the mature Man,· whose body will be th~ harmonious expression of his spiritual being And the movements of tl1is Man will be natural and beautiful like those of the free animals. The movement of the universe concentrating in an individual becomes what is termed the will; for example, tl1e movement of the earth, being the concentration of surrounding· forces, gives to the earth its individuality, its will of movement. -

Edition 31 Berliner Festspiele 2021

Ed. 31 '21 Die Editionsreihe der Berliner Festspiele erscheint bis zu sechsmal jährlich und präsentiert Originaltexte und Kunstpositionen. Bislang erschienen: Edition 1 Hanns Zischler, Großer Bahnhof (2012) Christiane Baumgartner, Nachtfahrt (2009) Edition 2 Mark Z. Danielewski, Only Revolutions Journals (2002 – 2004) Jorinde Voigt, Symphonic Area (2009) Edition 3 Marcel van Eeden, The Photographer (1945 – 1947), (2011 – 2012) Edition 4 Mark Greif, Thoreau Trailer Park (2012) Christian Riis Ruggaber, Contemplatio I–VII: The Act of Noting and Recording (2009 – 2010) Edition 5 David Foster Wallace, Kirche, nicht von Menschenhand erbaut (1999) Brigitte Waldach, Flashfiction (2012) Edition 6 Peter Kurzeck, Angehalten die Zeit (2013) Hans Könings, Spaziergang im Wald (2012) Edition 7 Botho Strauß, Kleists Traum vom Prinzen Homburg (1972) Yehudit Sasportas, SHICHECHA (2012) Edition 8 Phil Collins, my heart’s in my hand, and my hand is pierced, and my hand’s in the bag, and the bag is shut, and my heart is caught (2013) Edition 9 Strawalde, Nebengekritzle (2013) Edition 10 David Lynch, The Factory Photographs (1986–2000) Georg Klein, Der Wanderer (2014) Edition 11 Mark Lammert, Dimiter Gotscheff – Fünf Sitzungen / Five Sessions (2013) Edition 12 Tobias Rüther, Bowierise (2014) Esther Friedman, No Idiot (1976–1979) Edition 13 Michelangelo Antonioni, Zwei Telegramme (1983) Vuk D. Karadžić, Persona (2013) Edition 14 Patrick Ness, Every Age I Ever Was (2014) Clemens Krauss, Metabolizing History (2011 – 2014) Edition 15 Herta Müller, Pepita (2015) Edition 16 Tacita Dean, Event for a Stage (2015) Edition 17 Angélica Liddell, Via Lucis (2015) Edition 18 Karl Ove Knausgård, Die Rückseite des Gesichts (2014) Thomas Wågström, Nackar / Necks (2014) Edition 31 Berliner Festspiele 2021 Angela Rosenberg Pragmatiker auf heißem Boden Gerhart von Westerman, Kunstmanager und erster Intendant der Berliner Festwochen. -

Humanities (World Focus) Course Outline

Guiding Document: Humanities Course Outline Humanities (World Focus) Course Outline The Humanities To study humanities is to look at humankind’s cultural legacy-the sum total of the significant ideas and achievements handed down from generation to generation. They are not frivolous social ornaments, but rather integral forms of a culture’s values, ambitions and beliefs. UNIT ONE-ENLIGHTENMENT AND COMPARATIVE GOVERNMENTS (18th Century) HISTORY: Types of Governments/Economies, Scientific Revolution, The Philosophes, The Enlightenment and Enlightenment Thinkers (Hobbes, Locke, Montesquieu, Voltaire, Jefferson, Smith, Beccaria, Rousseau, Franklin, Wollstonecraft, Hidalgo, Bolivar), Comparing Documents (English Bill of Rights, A Declaration of the Rights of Man, Declaration of Independence, US Bill of Rights), French Revolution, French Revolution Film, Congress of Vienna, American Revolution, Latin American Revolutions, Napoleonic Wars, Waterloo Film LITERATURE: Lord of the Flies by William Golding (summer readng), Julius Caesar by Shakespeare (thematic connection), Julius Caesar Film, Neoclassicism (Denis Diderot’s Encyclopedie excerpt, Alexander Pope’s “Essay on Man”), Satire (Oliver Goldsmith’s Citizen of the World excerpt, Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels excerpt), Birth of Modern Novel (Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe excerpt), Musician Bios PHILOSOPHY: Rene Descartes (father of philosophy--prior to time period), Philosophes ARCHITECTURE: Rococo, Neoclassical (Jacques-Germain Soufflot’s Pantheon, Jean- Francois Chalgrin’s Arch de Triomphe) -

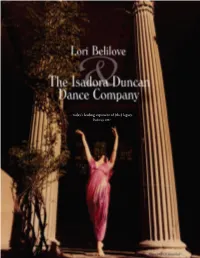

Today's Leading Exponent of (The) Legacy

... today’s leading exponent of (the) legacy. Backstage 2007 THE DANCER OF THE FUTURE will be one whose body and soul have grown so harmoniously together that the natural language of that soul will have become the movement of the human body. The dancer will not belong to a nation but to all humanity. She will not dance in the form of nymph, nor fairy, nor coquette, but in the form of woman in her greatest and purest expression. From all parts of her body shall shine radiant intelligence, bringing to the world the message of the aspirations of thousands of women. She shall dance the freedom of women – with the highest intelligence in the freest body. What speaks to me is that Isadora Duncan was inspired foremost by a passion for life, for living soulfully in the moment. ISADORA DUNCAN LORI BELILOVE Table of Contents History, Vision, and Overview 6 The Three Wings of the Isadora Duncan Dance Foundation I. The Performing Company 8 II. The School 12 ISADORA DUNCAN DANCE FOUNDATION is a 501(C)(3) non-profit organization III. The Historical Archive 16 recognized by the New York State Charities Bureau. Who Was Isadora Duncan? 18 141 West 26th Street, 3rd Floor New York, NY 10001-6800 Who is Lori Belilove? 26 212-691-5040 www.isadoraduncan.org An Interview 28 © All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced without the written permission of the Isadora Duncan Dance Foundation. Conceived by James Richard Belilove. Prepared and compiled by Chantal D’Aulnis. Interviews with Lori Belilove based on published articles in Smithsonian, Dance Magazine, The New Yorker, Dance Teacher Now, Dancer Magazine, Brazil Associated Press, and Dance Australia. -

![[Aleister] Crowley](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2560/aleister-crowley-1712560.webp)

[Aleister] Crowley

A REEVALUATION OF TI-IE LITERARY WORKS OF EDWARD ALEXANDER [ALEISTER] CROWLEY A Thesis Presented to The School of Graduate Studies Drake University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Charles Nicholas Serra II April 1991 A REEVALUATION OF THE LITERARY WORKS OF EDWARD ALEXANDER [ALEISTER] CROWLEY by Charles Nicholas Serra Il Approved by Committee: ~~.;.,. Dean of the School of Graduate Studies Dedicated to four instrumental people: For Aleister Crowley, who quested after "the light that never shone on land or sea"; for B. H. who provided patronage and patience; for Grace Eckley, who managed to nurse me through; and for L. L., "my Gitana, my Saliya," who has all the answers I lack, now in the ineffable. Unpublished Copyright. all rights reserved. 1991 1 A REEVALVATION OF THE LITERARY WORKS OF EDWARD ALEXANDER [ALEISTER] CROWLEY Table of Contents Page Abstract ., . ............. ..... ... .......... u Section One: Yeats and the Golden Dawn . Section Two: Augoeides, Maturity and Mysticism. ...... .. ..... 17 Section Three: Literary Decline, the War Years 36 Works Consulted. ...... ...... .. ........................... 44 Notes. .......... ....... ............ 49 Textual Appendix. ......................................... IA 11 A REEVALVAnON OF THE LITERARY WORKS OF EDWARD ALEXANDER [ALEISTER] CROWLEY Abstract For the last fifty years the poetry and prose of Edward Alexander [Aleister] Crowley (1875-1947) has been systematically ignored by scholars and critics on the narrow grounds that it deals with the occult sciences, is pornographic, or simply because detractors did not agree with Crowley's personal philosophy or life. Since the mid 1970's, however, academics have become increasingly interested in the mystical and occult content of William Butler Yeats's poetry, praising it for the same characteristics which have always been labeled "defects" in Crowley's work. -

Eckert & Kaun · Antiquariat Plantage 13 · 28215 Bremen (Ladengeschäft

Eckert & Kaun · Antiquariat Plantage 13 · 28215 Bremen (Ladengeschäft: Richtweg 4 – 28195 Bremen) Telefon 0421-72204 · Fax 0421-70 76 58 EMail: [email protected] UID/VAT-Nr. DE 261521379 Geschäftszeiten: Montag bis Freitag 11 – 18 Uhr Samstag 11 – 15 Uhr Mitglied im Verband deutscher Antiquare e.V. Umschlag vorne: Moholy-Nagy, Nr. 802 Umschlag hinten: Anonym, Nr. 1162 KATALOG 16 Winter 2013/14 Ältere Literatur 1 – 177 Literatur und illustrierte Bücher 178 – 871 Kunst und Kunstgeschichte 872 – 1061 Fotografie 1062 – 1206 Varia 1207 – 1271 Lieferbedingungen Das Angebot ist freibleibend. Es besteht kein Lieferzwang. Die Preise verstehen sich in EURO inclusive der gesetzlichen Mehrwertsteuer. Der Versand erfolgt auf Kosten des Bestellers. Die Rechnung ist zahlbar rein netto nach Er halt. Bei begründeten Beanstandungen wird jede Lieferung zurück genommen, jedoch nicht später als 8 Tage nach Empfang. Eigentumsvor behalt nach § 455 BGB. Erfüllungsort und Gerichtsstand unter ausdrücklichem Einbezug des Mahnverfahrens ist für beide Teile Bremen. Lieferung an unbekannte Besteller gegen Vorausrech nung oder durch Nachnahme. Widerrufsrecht: Sie können Ihre Vertragserklärung inner - halb von einem Monat ohne Angaben von Gründen in Textform (Brief, e-mail etc.) oder durch Rücksendung der Sache widerrufen. Die Frist beginnt frühestens mit Erhalt dieser Belehrung. Zur Wahrung der Widerrufsfrist genügt die rechtzeitige Absendung des Widerrufs oder der Sache. Widerruf ist zur richten an: Eckert & Kaun GbR, Plantage 13, 28215 Bremen Bankverbindungen Sparkasse in Bremen Kto.-Nr. 1068170 BLZ 290 501 01 IBAN BIC DE88 2905 0101 0001 0681 70 SBREDE22 Postbank Hamburg Kto.-Nr. 5288 73-207 BLZ 200 100 20 IBAN BIC DE87 2001 0020 0528 8732 07 PBNKDEFF 3 ÄLTERE LITERATUR selben von Ferdinand Delbrück. -

La Danse Contemporaine En France Dans Les Années 1970

13-Annexe-VI:comite-histoire 30/05/07 17:55 Page 221 ANNEXE VI La danse contemporaine en France dans les années 1970 LES POINTS DE FRAGILITÉ La danse ne dispose pas d’institutions publiques autonomes Alors qu’existe déjà sur le territoire un réseau de centres dramatiques natio - naux, de maisons de la culture, de centres d’action culturelle dirigés presque exclusivement par des hommes de théâtre, alors que se constitue, conformément au plan de Marcel Landowski 1, un maillage du territoire en ce qui concerne les institutions musicales de diffusion et de formation (orchestres et conservatoires), les rares institutions de formation ou de dif - fusion chorégraphiques sont des entités insérées dans des théâtres lyriques 2 ou des conservatoires de musique dont aucun n’est dirigé par un danseur et qui n’ont ni budget autonome ni indépendance administrative. Ce domaine artistique n’a pas d’existence administrative propre Cette faiblesse du réseau institutionnel explique sans doute en partie le fait que le ministère de la Culture, au cours de l’individuation progressive des secteurs artistiques qui marque son évolution depuis 1959, n’ait pas éprou- vé le besoin de créer pour la danse de structure administrative spécifique. À la direction de la Musique, de l’Art lyrique et de la Danse (D MALD ), deux personnes seulement sont chargées – entre autres responsabilités – de l’en - 1. Nommé premier directeur de la Musique, de l’Art lyrique et de la Danse par André Bettencourt en décembre 1970, Marcel Landowski avait été auparavant chef du service de la musique (de 1966 à 1969), service rattaché à la direction générale des Arts et Lettres, puis chef du service de la musique, de l’art lyrique et de la danse (le terme n’apparaît qu’en 1969), service rattaché à la nou - velle direction des Spectacles, de la Musique et des Lettres 2. -

Susanne Linke- Curriculum Vitae

Susanne Linke- Curriculum vitae 1944 born on June 19th in Lüneburg 1953-55 weekly visits to Medau gymnastics for children with Ruth Pinzler in Berlin 1960-63 1-2x per week dance gymnastics with Ruth Grau in Hofheim/Ts near Frankfurt/Main 1963 first meeting with the solo dance legend Dore Hoyer for the „Walpurgis Nacht“ rehearsals for the opening of the new theater in Frankfurt 1964-67 first study of dance with Mary Wigman in the Rheinbabenallee 34, Berlin- Dahlem 1967 first public dance appearance at the Academy of the Arts Berlin as a student in the piece „Countdown für Orpheus“ as a collective work by the group Motion, directed by Hellmut Fricke-Gottschild, Manfred Fischbeck und Gitta Herrmann 1967-70 second course of study at the Folkwang-Hochschule dance department in Essen, directed by Prof. Hans Züllig 1970-73 dancer at the Folkwang Tanzstudio/FTS, artistic director: Pina Bausch. First choreographic experiments „Mono“, „Trio“, „Habe die Ehre... zum Ball“ 1973-74 dancer at Rotterdams Dans Center, directed by Inneken Sleuter 1974-75 return to the Folkwang dance department without a position. 3 choreographies with dancers are created with dancers from the Folkwang masterclass: „Danse funèbre“ won the 3rd jury prize of the „Ballet Pour Demain“ in choreografic competition in Bagnolet, Paris. „Puppe“ won the 2nd jury prize at the 7th internationalen choreografic competition in cologne. „Trop tard“ won the 2nd jury prize at the „Festival Estival de Paris“ 1975 creation of the choreography „L´histoire obscure“ as a further development of „Habe die Ehre...“ 1975-78 gifted support for choreography, together with Reinhild Hoffmann at the Folkwang-Hochschule für Tanz, directed by Prof.