Air Masses and Weather Fronts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Comparison of Precipitation from Maritime and Continental Air

254 BULLETIN AMERICAN METEOROLOGICAL SOCIETY A Comparison of Precipitation from Maritime and Continental Air GEORGE S. BENTON 1 and ROBERT T. BLACKBURN 2 OR many decades, knowledge of atmospheric These 123 periods of precipitation for 1946 were F movements of water vapor has lagged behind grouped as indicated below. Classifications for other phases of meteorological information. In which precipitation was necessarily from maritime recent years, however, the accumulation of upper- air are marked with an asterisk; classifications for air data has stimulated hydrometeorological re- which precipitation was necessarily from contin- search. One interesting problem considered has ental air are marked with a double asterisk. For been the source of precipitation classified accord- all other classifications, precipitation may have ing to air mass. occurred either from maritime or continental air, In 1937 Holzman [2] advanced the hypothesis depending upon the individual circumstances. that the great majority of precipitation comes from maritime air masses. Although meteorologists I. Cold front have generally been willing to accept this hypothe- A. Pre-frontal precipitation sis on the basis of their qualitative familiarity with *1. MT present throughout tropo- atmospheric phenomena, little has been done to sphere determine quantitatively the percentage of pre- **2. cP present throughout tropo- cipitation which can actually be traced to maritime sphere air. Certainly the precipitation from continental 3. MT overriding cP in warm sec- air masses must be measurable and must vary in tor importance from region to region. B. Post-frontal precipitation In the course of an analysis of the role of the 1. MT overriding cP atmosphere in the hydrologic cycle [1], the au- *a. -

Air Masses and Fronts

CHAPTER 4 AIR MASSES AND FRONTS Temperature, in the form of heating and cooling, contrasts and produces a homogeneous mass of air. The plays a key roll in our atmosphere’s circulation. energy supplied to Earth’s surface from the Sun is Heating and cooling is also the key in the formation of distributed to the air mass by convection, radiation, and various air masses. These air masses, because of conduction. temperature contrast, ultimately result in the formation Another condition necessary for air mass formation of frontal systems. The air masses and frontal systems, is equilibrium between ground and air. This is however, could not move significantly without the established by a combination of the following interplay of low-pressure systems (cyclones). processes: (1) turbulent-convective transport of heat Some regions of Earth have weak pressure upward into the higher levels of the air; (2) cooling of gradients at times that allow for little air movement. air by radiation loss of heat; and (3) transport of heat by Therefore, the air lying over these regions eventually evaporation and condensation processes. takes on the certain characteristics of temperature and The fastest and most effective process involved in moisture normal to that region. Ultimately, air masses establishing equilibrium is the turbulent-convective with these specific characteristics (warm, cold, moist, transport of heat upwards. The slowest and least or dry) develop. Because of the existence of cyclones effective process is radiation. and other factors aloft, these air masses are eventually subject to some movement that forces them together. During radiation and turbulent-convective When these air masses are forced together, fronts processes, evaporation and condensation contribute in develop between them. -

WHAT IS METEOROLOGY? Meteorology Is the Science of Weather

WHAT IS METEOROLOGY? Meteorology is the science of weather. It is essentially an inter-disciplinary science because the atmosphere, land and ocean constitute an integrated system. The three basic aspects of meteorology are observation, understanding and prediction of weather. There are many kinds of routine meteorological observations. Some of them are made with simple instruments like the thermometer for measuring temperature or the anemometer for recording wind speed. The observing techniques have become increasingly complex in recent years and satellites have now made it possible to monitor the weather globally. Countries around the world exchange the weather observations through fast telecommunications channels. These are plotted on weather charts and analysed by professional meteorologists at forecasting centres. Weather forecasts are then made with the help of modern computers and supercomputers. Weather information and forecasts are of vital importance to many activities like agriculture, aviation, shipping, fisheries, tourism, defence, industrial projects, water management and disaster mitigation. Recent advances in satellite and computer technology have led to significant progress in meteorology. Our knowledge of the weather is, however, still incomplete. WHAT IS SYNOPTIC METEOROLOGY? Weather observations, taken on the ground or on ships, and in the upper atmosphere with the help of balloon soundings, represent the state of the atmosphere at a given time. When the data are plotted on a weather map, we get a synoptic view of the worlds weather. Hence day-to-day analysis and forecasting of weather has come to be known as synoptic meteorology. It is the study of the movement of low pressure areas, air masses, fronts, and other weather systems like depressions and tropical cyclones. -

Surface Cyclolysis in the North Pacific Ocean. Part I

748 MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW VOLUME 129 Surface Cyclolysis in the North Paci®c Ocean. Part I: A Synoptic Climatology JONATHAN E. MARTIN,RHETT D. GRAUMAN, AND NATHAN MARSILI Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences, University of WisconsinÐMadison, Madison, Wisconsin (Manuscript received 20 January 2000, in ®nal form 16 August 2000) ABSTRACT A continuous 11-yr sample of extratropical cyclones in the North Paci®c Ocean is used to construct a synoptic climatology of surface cyclolysis in the region. The analysis concentrates on the small population of all decaying cyclones that experience at least one 12-h period in which the sea level pressure increases by 9 hPa or more. Such periods are de®ned as threshold ®lling periods (TFPs). A subset of TFPs, referred to as rapid cyclolysis periods (RCPs), characterized by sea level pressure increases of at least 12 hPa in 12 h, is also considered. The geographical distribution, spectrum of decay rates, and the interannual variability in the number of TFP and RCP cyclones are presented. The Gulf of Alaska and Paci®c Northwest are found to be primary regions for moderate to rapid cyclolysis with a secondary frequency maximum in the Bering Sea. Moderate to rapid cyclolysis is found to be predominantly a cold season phenomena most likely to occur in a cyclone with an initially low sea level pressure minimum. The number of TFP±RCP cyclones in the North Paci®c basin in a given year is fairly well correlated with the phase of the El NinÄo±Southern Oscillation (ENSO) as measured by the multivariate ENSO index. -

Weather Forecasting and to the Measuring Weather Data, Instruments, and Science That Make Forecasting Accurate

Delta Science Reader WWeathereather ForecastingForecasting Delta Science Readers are nonfiction student books that provide science background and support the experiences of hands-on activities. Every Delta Science Reader has three main sections: Think About . , People in Science, and Did You Know? Be sure to preview the reader Overview Chart on page 4, the reader itself, and the teaching suggestions on the following pages. This information will help you determine how to plan your schedule for reader selections and activity sessions. Reading for information is a key literacy skill. Use the following ideas as appropriate for your teaching style and the needs of your students. The After Reading section includes an assessment and writing links. VERVIEW Students will O understand the main factors that cause The Delta Science Reader Weather weather and produce weather changes Forecasting introduces students to the learn about the various instruments for world of weather forecasting and to the measuring weather data, instruments, and science that make forecasting accurate. Students will explore identify some of the elements of severe the six main weather factors—temperature, weather, and distinguish between weather air pressure, wind, humidity, precipitation, and climate and cloudiness—as well as discover the discuss the function of nonfiction text difference between weather and climate. elements such as the table of contents, The book also contains a biographical headings, tables, captions, and glossary sketch of tornado expert Tetsuya Theodore Fujita and information about two other kinds interpret photographs and graphics— of weather scientists: climatologists and diagrams, illustrations, weather maps— hurricane hunters. Students will find out to answer questions how a weather satellite works and how complete a KWL chart to track new different types of winds get their names. -

Weather Charts Natural History Museum of Utah – Nature Unleashed Stefan Brems

Weather Charts Natural History Museum of Utah – Nature Unleashed Stefan Brems Across the world, many different charts of different formats are used by different governments. These charts can be anything from a simple prognostic chart, used to convey weather forecasts in a simple to read visual manner to the much more complex Wind and Temperature charts used by meteorologists and pilots to determine current and forecast weather conditions at high altitudes. When used properly these charts can be the key to accurately determining the weather conditions in the near future. This Write-Up will provide a brief introduction to several common types of charts. Prognostic Charts To the untrained eye, this chart looks like a strange piece of modern art that an angry mathematician scribbled numbers on. However, this chart is an extremely important resource when evaluating the movement of weather fronts and pressure areas. Fronts Depicted on the chart are weather front combined into four categories; Warm Fronts, Cold Fronts, Stationary Fronts and Occluded Fronts. Warm fronts are depicted by red line with red semi-circles covering one edge. The front movement is indicated by the direction the semi- circles are pointing. The front follows the Semi-Circles. Since the example above has the semi-circles on the top, the front would be indicated as moving up. Cold fronts are depicted as a blue line with blue triangles along one side. Like warm fronts, the direction in which the blue triangles are pointing dictates the direction of the cold front. Stationary fronts are frontal systems which have stalled and are no longer moving. -

History of Frontal Concepts Tn Meteorology

HISTORY OF FRONTAL CONCEPTS TN METEOROLOGY: THE ACCEPTANCE OF THE NORWEGIAN THEORY by Gardner Perry III Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June, 1961 Signature of'Author . ~ . ........ Department of Humangties, May 17, 1959 Certified by . v/ .-- '-- -T * ~ . ..... Thesis Supervisor Accepted by Chairman0 0 e 0 o mmite0 0 Chairman, Departmental Committee on Theses II ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The research for and the development of this thesis could not have been nearly as complete as it is without the assistance of innumerable persons; to any that I may have momentarily forgotten, my sincerest apologies. Conversations with Professors Giorgio de Santilw lana and Huston Smith provided many helpful and stimulat- ing thoughts. Professor Frederick Sanders injected thought pro- voking and clarifying comments at precisely the correct moments. This contribution has proven invaluable. The personnel of the following libraries were most cooperative with my many requests for assistance: Human- ities Library (M.I.T.), Science Library (M.I.T.), Engineer- ing Library (M.I.T.), Gordon MacKay Library (Harvard), and the Weather Bureau Library (Suitland, Md.). Also, the American Meteorological Society and Mr. David Ludlum were helpful in suggesting sources of material. In getting through the myriad of minor technical details Professor Roy Lamson and Mrs. Blender were indis-. pensable. And finally, whatever typing that I could not find time to do my wife, Mary, has willingly done. ABSTRACT The frontal concept, as developed by the Norwegian Meteorologists, is the foundation of modern synoptic mete- orology. The Norwegian theory, when presented, was rapidly accepted by the world's meteorologists, even though its several precursors had been rejected or Ignored. -

Extratropical Cyclones and Anticyclones

© Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC. NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION Courtesy of Jeff Schmaltz, the MODIS Rapid Response Team at NASA GSFC/NASA Extratropical Cyclones 10 and Anticyclones CHAPTER OUTLINE INTRODUCTION A TIME AND PLACE OF TRAGEDY A LiFE CYCLE OF GROWTH AND DEATH DAY 1: BIRTH OF AN EXTRATROPICAL CYCLONE ■■ Typical Extratropical Cyclone Paths DaY 2: WiTH THE FI TZ ■■ Portrait of the Cyclone as a Young Adult ■■ Cyclones and Fronts: On the Ground ■■ Cyclones and Fronts: In the Sky ■■ Back with the Fitz: A Fateful Course Correction ■■ Cyclones and Jet Streams 298 9781284027372_CH10_0298.indd 298 8/10/13 5:00 PM © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC. NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION Introduction 299 DaY 3: THE MaTURE CYCLONE ■■ Bittersweet Badge of Adulthood: The Occlusion Process ■■ Hurricane West Wind ■■ One of the Worst . ■■ “Nosedive” DaY 4 (AND BEYOND): DEATH ■■ The Cyclone ■■ The Fitzgerald ■■ The Sailors THE EXTRATROPICAL ANTICYCLONE HIGH PRESSURE, HiGH HEAT: THE DEADLY EUROPEAN HEAT WaVE OF 2003 PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER ■■ Summary ■■ Key Terms ■■ Review Questions ■■ Observation Activities AFTER COMPLETING THIS CHAPTER, YOU SHOULD BE ABLE TO: • Describe the different life-cycle stages in the Norwegian model of the extratropical cyclone, identifying the stages when the cyclone possesses cold, warm, and occluded fronts and life-threatening conditions • Explain the relationship between a surface cyclone and winds at the jet-stream level and how the two interact to intensify the cyclone • Differentiate between extratropical cyclones and anticyclones in terms of their birthplaces, life cycles, relationships to air masses and jet-stream winds, threats to life and property, and their appearance on satellite images INTRODUCTION What do you see in the diagram to the right: a vase or two faces? This classic psychology experiment exploits our amazing ability to recognize visual patterns. -

NWS Unified Surface Analysis Manual

Unified Surface Analysis Manual Weather Prediction Center Ocean Prediction Center National Hurricane Center Honolulu Forecast Office November 21, 2013 Table of Contents Chapter 1: Surface Analysis – Its History at the Analysis Centers…………….3 Chapter 2: Datasets available for creation of the Unified Analysis………...…..5 Chapter 3: The Unified Surface Analysis and related features.……….……….19 Chapter 4: Creation/Merging of the Unified Surface Analysis………….……..24 Chapter 5: Bibliography………………………………………………….…….30 Appendix A: Unified Graphics Legend showing Ocean Center symbols.….…33 2 Chapter 1: Surface Analysis – Its History at the Analysis Centers 1. INTRODUCTION Since 1942, surface analyses produced by several different offices within the U.S. Weather Bureau (USWB) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA’s) National Weather Service (NWS) were generally based on the Norwegian Cyclone Model (Bjerknes 1919) over land, and in recent decades, the Shapiro-Keyser Model over the mid-latitudes of the ocean. The graphic below shows a typical evolution according to both models of cyclone development. Conceptual models of cyclone evolution showing lower-tropospheric (e.g., 850-hPa) geopotential height and fronts (top), and lower-tropospheric potential temperature (bottom). (a) Norwegian cyclone model: (I) incipient frontal cyclone, (II) and (III) narrowing warm sector, (IV) occlusion; (b) Shapiro–Keyser cyclone model: (I) incipient frontal cyclone, (II) frontal fracture, (III) frontal T-bone and bent-back front, (IV) frontal T-bone and warm seclusion. Panel (b) is adapted from Shapiro and Keyser (1990) , their FIG. 10.27 ) to enhance the zonal elongation of the cyclone and fronts and to reflect the continued existence of the frontal T-bone in stage IV. -

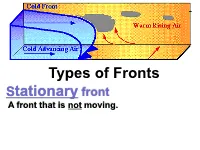

Types of Fronts Stationary Front a Front That Is Not Moving

Types of Fronts Stationary front A front that is not moving. Types of Fronts Cold front is a leading edge of colder air that is replacing warmer air. Types of Fronts Warm front is a leading edge of warmer air that is replacing cooler air. Types of Fronts Occluded front: When a cold front catches up to a warm front. Types of Fronts Dry Line Separates a moist air mass from a dry air mass. A.Cold Front is a transition zone from warm air to cold air. A cold front is defined as the transition zone where a cold air mass is replacing a warmer air mass. Cold fronts generally move from northwest to southeast. The air behind a cold front is noticeably colder and drier than the air ahead of it. When a cold front passes through, temperatures can drop more than 15 degrees within the first hour. The station east of the front reported a temperature of 55 degrees Fahrenheit while a short distance behind the front, the temperature decreased to 38 degrees. An abrupt temperature change over a short distance is a good indicator that a front is located somewhere in between. B. Warm Front. • A transition zone from cold air to warm air. • A warm front is defined as the transition zone where a warm air mass is replacing a cold air mass. Warm fronts generally move from southwest to northeast . The air behind a warm front is warmer and more moist than the air ahead of it. When a warm front passes through, the air becomes noticeably warmer and more humid than it was before. -

ESSENTIALS of METEOROLOGY (7Th Ed.) GLOSSARY

ESSENTIALS OF METEOROLOGY (7th ed.) GLOSSARY Chapter 1 Aerosols Tiny suspended solid particles (dust, smoke, etc.) or liquid droplets that enter the atmosphere from either natural or human (anthropogenic) sources, such as the burning of fossil fuels. Sulfur-containing fossil fuels, such as coal, produce sulfate aerosols. Air density The ratio of the mass of a substance to the volume occupied by it. Air density is usually expressed as g/cm3 or kg/m3. Also See Density. Air pressure The pressure exerted by the mass of air above a given point, usually expressed in millibars (mb), inches of (atmospheric mercury (Hg) or in hectopascals (hPa). pressure) Atmosphere The envelope of gases that surround a planet and are held to it by the planet's gravitational attraction. The earth's atmosphere is mainly nitrogen and oxygen. Carbon dioxide (CO2) A colorless, odorless gas whose concentration is about 0.039 percent (390 ppm) in a volume of air near sea level. It is a selective absorber of infrared radiation and, consequently, it is important in the earth's atmospheric greenhouse effect. Solid CO2 is called dry ice. Climate The accumulation of daily and seasonal weather events over a long period of time. Front The transition zone between two distinct air masses. Hurricane A tropical cyclone having winds in excess of 64 knots (74 mi/hr). Ionosphere An electrified region of the upper atmosphere where fairly large concentrations of ions and free electrons exist. Lapse rate The rate at which an atmospheric variable (usually temperature) decreases with height. (See Environmental lapse rate.) Mesosphere The atmospheric layer between the stratosphere and the thermosphere. -

275 Tor Bergeron's Uber Die

JULY,1931 MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW 275 The aooperative stations are nearer the c.rops, being gage: These are read at about 4 p. m. or 8 a. m. and the mostly in small towns, or even on farms, in some in- maximum and niininiuin temperature, set maximum stances, but they measure only rainfall and temperature temperature, and total rainfall entered on forms. Where once a day and have no self-recording instruments that are the details? How much sunshine, what was soil keep a continuous record. Thus, for these which are temperature, when did rain occur, how long were tempera- more directly applicable, many weather phases are not tures above or below a significant value, what was the available. relative humidity, rate of evaporation, etc.? The crop statistics are even more hazy and generalized, Even if the above questions were satisfactorily answered in addition to being relatively inaccessible. We can find how can we be sure that, we have everything we need? easily the estimated yield per acre or total acreage, for the Maybe we need leaf temperature, intensity of solar radia- most available data give these figures on a State unit tion, plant transpiration, moisture of tlie soil at different basis, but yields often vary widely in different parts of a depths, and many other details too numerous to mention. State. Loc,al, even in most places county, temperature and rainfall data are available, but what about correspond- CONCLUSION ing yield figures? They are to be had in some individual Are we doing everything possible to facilitate the study State publications, but a complete file for one State is OI crop production in its relation to the weather on a difficult to find outside the issuing office and then the large scale, or even in local areas? There have been some series is rarely carried back far enough to be of material beginnings.