Toward a Theory of Olympic Lnternationalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Rtet^R Sunning Ijyralb LEAGUE CALLS PARLEY on REICH REARMAMENT

jfAlt( l 1 , 1 ^ OAOLV GOtOULATION The Men’s chorus « f the Second H i* weekly bridge and eetbeck AVtM AOM Emanuel Lutheran church Sunday FstechBl et O. 8. W( Ooagregatloaal church win prepare p ^ y of the Hencheeter Green at 7 o’clock. This chorus is cloeely tor tha month ef Fsbrnary, IMS ABOUT TOWM and servo the monthly parish sup Community club will take place to SCHUBERT SINGERS connected with the Beethoven Glee Pinochle Tonight per tomorrow night at 6:30 at the morrow night at 8 o’clock. Novelty Club In that the present director of PAPER HANGING u , v s HPnit****""*"** Trib* No. S8, I. O. church.- They will also provide a door prizea will be awarded and the the Beethovens, G. Albert Pearson, AT MASONIC TEMPLE 83.60 A ROOM. \ 5,486 Fair ahd esUer tonight; RntnrOny ‘m IL. will tiold It! regular meeting IKeJIYIlALtCo musical program to follow the meal. usual caah prises given the winners HERE W SUNDAY organized and directed the Schu I Alsa Curry WUIpaqMr. Member et the Andft ooMer with rain beginning Sntardnj • « llidcer ban tomorrow evening at 8:00 P. M. •rMANCHF.StFP/’OHN.'w The fee is pUtced s o ' that whole In each section. The gamea will ha berts last year. Bnraan ef (Jlrealattona an rtet^r Sunning IJyralb oe Bight. 'Ife rd o e k . famUles will feel able to attend. followed by a aocial time during — All Men Invited! — There Is a close bond of friend A. K A N E H L 3 TO 6 SPECIALS which refreshmenta wlU be served ship between these two organiza Palaler .ml Daeormtor U Owing to tbe poatponemwt of tba Admission 25e. -

INTERPOL À LYON Une Collaboration Inédite, Un Impact Sur La Ville, Un Avenir Incertain

Institut d'Études Politiques de Lyon INTERPOL À LYON Une collaboration inédite, un impact sur la ville, un avenir incertain Christophe RAMAMONJY-RATRIMO Mémoire de séminaire, Histoire politique des XIXe et XXe siècles Sous la direction de Bruno BENOÎT Soutenu le 7 septembre 2010 Jury composé de Bruno BENOÎT, professeur d’Histoire et Gilles VERGNON, maître de conférences en Histoire à l’IEP de Lyon Table des matières Remerciements . 5 Avant-propos . 6 Introduction . 8 Livre I : Lyon, capitale mondiale de la police . 14 Chapitre 1 : Une histoire française . 14 A. Les sources de l’accord . 14 B. Le contentieux opposant l’Eglise de scientologie à Interpol . 15 C. La loi informatique et liberté . 16 Chapitre 2 : Un déménagement nécessaire . 19 A. « Une bonne blague » . 20 B. Lyon capitale de la filature . 25 C. Fonctionnement de l’organisation : le secrétariat, le siège d’Interpol ? . 30 Chapitre 3 : Le parti architectural . 34 A. Une intégration nécessaire dans l’environnement de la cité internationale . 34 B. Lyon inaugure Mitterrand . 36 C. Interpol dans sa forteresse de verre . 39 Livre II : Un inpact sur la ville et la région . 42 Chapitre 1 : « Une valeur d’entraînement considérable » . 42 A. Une ouverture sur le monde . 42 B. Des retombées économiques . 43 C. Un nouveau regard sur la ville . 44 Chapitre 2 : une crédibilité pour la ville . 45 A. Le 1er centre de décisions . 45 B. Des organismes internationaux . 45 C. Des organismes de recherche . 46 Chapitre 3 : Un lycée mis sur orbite . 47 A. Un retour à la tradition . 48 B. Un concours d’architecte mémorable . -

Gilbert Molinier Lorsqu'alain Badiou Se Fait Historien : Heidegger, La

Texto ! Textes et cultures, vol. XXIV, n°3 (2019) Gilbert Molinier Lorsqu’Alain Badiou se fait historien : Heidegger, la Deuxième Guerre mondiale, et coetera « [L]e spectacle que m’a offert l’université a contribué à m’exorciser complètement, à me délivrer d’une catharsis qui s’est achevée à la Sorbonne quand j’ai vu mes collègues, tous ces singes qui lisaient Heidegger et le citaient en allemand. »1 Vladimir Jankélévitch Résumé. — Cette étude traite d’une dénégation collective. Situant ses recherches au niveau et dans la lignée des prestigieux penseurs de la question de l’Être, Parménide, Aristote, Malebranche…, Alain Badiou rencontre Martin Heidegger. Or, celui-ci est soupçonné d’avoir été et/ou d’avoir toujours été un nazi inconditionnel. Souhaitant effacer une telle tache, Alain Badiou affirme, d’une part : « [Il] n’y a absolument pas besoin de chercher dans sa philosophie des preuves qu’il était nazi, puisqu’il était nazi, voilà ! […] » ; d’autre part et en même temps, il infirme : « C’est bien plutôt dans ce qu’il a fait, ce qu’il a dit, etc. » Cet « etc. » contient donc « ce qu’il a pensé, ce qu’il a écrit » . C’est sur une telle dénégation collective que s’appuient encore l’enseignement et la recherche universitaires dans de nombreux pays, en particulier en France. Or, une dénégation si marquée ne va pas sans produire des effets négatifs. Resümee. — Ursprung der folgenden Bemerkungen ist eine kollektive Verneinung. Alain Badiou, der es liebt, seine Forschungen auf die Ebene und in Übereinstimmung mit den angesehenen Denkern zur Frage des Seins, Parménides, Aristoteles, Malebranche… zu stellen, trifft einen gewissen Martin Heidegger. -

Die Charlottenburger

Dieter Schenk Die Führerschule der NS-Sicherheitspolizei und die „Charlottenburger“ im Bundeskriminalamt „Reichskristallnacht“ bezeichnete den reichsweiten Pogrom gegen Juden vor siebzig Jahren am 9./10. November 1938. Die Herkunft des Begriffs ist nicht geklärt. Die Auslösung erfolgte durch eine Hetzrede Goebbels nach Zustimmung Hitlers. Die offizielle Propaganda begründete die Massaker mit der Ermordung des Diplomaten Ernst vom Rath in Paris durch den siebzehnjährigen Juden Herschel Grünspan. In einem barbarischen Terrorakt setzten SA- und NSDAP-Mitglieder Synagogen in Brand, zerstörten etwa 7000 Geschäfte jüdischer Einzelhändler und verwüsteten Wohnungen der Juden. Sie töten nach offiziellen Angaben insgesamt 91 Personen. Die Zahl derer, die infolge von Leid und Schrecken umkamen, ist nicht bekannt. An den Aktionen beteiligten sich auch Angehörige der HJ und weiterer SS-Organisationen. Der Mob nutzte die Chance zu Plünderungen. Die Gestapo organisierte die Verschleppung von etwa 26 000 jüdischer Männer und Jugendlicher in die KZ Buchenwald, Dachau und Sachsenhausen. Viele von ihnen kamen dort infolge körperlicher und psychischer Schikanen oder durch Medikamentenentzug ums Leben. Anderen wurde der Verzicht auf Eigentum abgezwungen. Die Masse der Inhaftierten kam erst nach Auswanderungserklärungen frei. Als „Sühneleistung“ wurde den Juden der Betrag von einer Milliarde Reichsmark auferlegt. ****** Die NS-Täter, auf die ich noch näher eingehen will, begannen ihren Lehrgang an der Führerschule der Sicherheitspolizei in Charlottenburg am 12. Oktober 1938, also knapp vier Wochen vor der Reichspogromnacht. Ob sie daran beteiligt waren oder wie sie darauf reagierten, ist nicht überliefert. Dass sie Mitleid oder Bedauern empfanden, wird man wohl ausschließen können. ****** Ursprünglich war das 1927 errichtete Polizeiinstitut Charlottenburg eine Ausbildungs- und Forschungsstätte der preußischen Polizei neben der Höheren Polizeischule in Eiche. -

THE BUNDESKRIMINALAMT the PROFILE Published by The

THE BUNDESKRIMINALAMT THE PROFILE Published by the BUNDESKRIMINALAMT Public Relations 65173 Wiesbaden Conception and Layout: KARIUS & PARTNER GMBH Gerlinger Straße 77, 71229 Leonberg Text: Bundeskriminalamt Printed by: DPS GmbH, Bad Homburg Full reproduction only with the written permission of the Bundeskriminalamt. 2 Contents Welcome to the Bundeskriminalamt 5 How we view our Tasks 6 Our Mandate 6 The Bundeskriminalamt as a Central Agency 8 The Investigation 10 International Functions 11 Protection Tasks and Prevention 12 Administrative Functions 12 Our Staff 13 Information available on the Internet 13 Our Organisation 13 The Divisions of the Bundeskriminalamt 14 Division IK, International Coordination 14 Division ST, State Security 16 Division SO, Serious and Organised Crime 18 Division SG, Protection Division 20 Division ZD, Central CID Services 20 Division KI, Institute of Law Enforcement Studies and Training 22 Division KT, Forensic Science Institute 24 Division IT, Information Technology 26 Division ZV, Central and Administrative Affairs 26 History of the Bundeskriminalamt 27 Status 01/2008 3 4 WELCOME TO THE BUNDESKRIMINALAMT! The Bundeskriminalamt dates back to March 1951. At the world. It poses a great challenge to security agen- that point in time, the ”Law on the Establishment of cies at national and international level and makes it a Federal Criminal Police Office” came into force. A necessary to review our own organisation and the short time afterwards the ”Criminal Police Office for interaction with other agencies of the security archi- the British Zone” in Hamburg became the Bundes- tecture. kriminalamt (Federal Criminal Police Office), abbre- viated BKA. Legislators thus acted on the authority The resulting new organisation of the state security granted by the German Constitution to set up central division of the Bundeskriminalamt distinctly strength- agencies at Federal level for police information and ens our investigative potential in the fight against communications as well as for criminal police work. -

Eddie Steele (Norwood)

© www.boxinghistory.org.uk - all rights reserved This page has been brought to you by www.boxinghistory.org.uk Click on the image above to visit our site Eddie Steele (Norwood) Active: 1928-1938 Weight classes fought in: Recorded fights: 62 contests (won: 39 lost: 17 drew: 5 other: 1) Fight Record 1928 Oct 22 Frank Berwick (Birmingham) LPTS(4) Crystal Palace, Sydenham Source: Boxing 23/10/1928 page 235 (Heavyweight competition - semi-final) Oct 22 Steve Taylor (Hinckley) WPTS(4) Crystal Palace, Sydenham Source: Boxing 23/10/1928 page 235 (Heavyweight competition - 1st series) Nov 15 Pat Logue (Belfast) WKO2(6) Premierland, Whitechapel Source: Boxing 20/11/1928 page 292 Referee: Jack Hart Dec 3 Steve Taylor (Hinckley) WKO3(10) Crystal Palace, Sydenham Source: Boxing 04/12/1928 pages 329 and 328 Promoter: JT Hulls Dec 10 Charlie Groom (Marylebone) WPTS(10) Crystal Palace, Sydenham Source: Boxing 12/12/1928 pages 345 and 344 Attendance: 4000 1929 Jan 23 Battling Sullivan (Preston) NC8(15) Baths Hall, Ipswich Source: Boxing 30/01/1929 page 454 Referee: Jack Hart Promoter: Ben Cooper & N Shaw Feb 21 Bob Carvill (Bridlington) DRAW(6) Crystal Palace, Sydenham Source: Boxing 27/02/1929 pages 509 and 508 Carvill was Northern Area Heavyweight Champion 1932-33. May 20 Reggie Meen (Desborough) WPTS(12) Crystal Palace, Sydenham Source: Boxing 22/05/1929 page 683 Meen was British Heavyweight Champion 1931-32. Jun 18 Reggie Meen (Desborough) LKO2(15) Junior Training Hall, Leicester Source: Boxing 26/06/1929 page 21 Referee: Ben Green(Leeds) Sep 23 Abe Lipschitz (USA) WPTS(4) New York City USA Source: Vic Hardwicke (Boxing Historian) Nov 4 Andy Smulley (USA) WPTS(6) Philadelphia USA Source: South Wales Echo Dec Andy Shulley (USA) WPTS(6) Philadelphia USA Source: Vic Hardwicke (Boxing Historian) Dec 9 Bill Darling (USA) LPTS(4) New York City USA Source: Vic Hardwicke (Boxing Historian) 1930 Mar 5 Dave Forbes (Glasgow) LDSQ7(10) Stadium Club, Holborn Source: Boxing 12/03/1930 page 577 Forbes boxed for the Scottish Heavyweight Title 1929. -

Local Dentist President of Elected Medical Ass'n NAAGP Hoi Meet Sunda1

mmMg . cH#lW«* V/J- EDICAL ASSOCIATION MEETS HERE JUNE COVERING HOME OWNED EVANSVILLE fi HOME OPERATED AND ADJOINING TERRITORY THE EVANSVILLE ARGUS VOL. 1—NO. 1 EVANSVILLE, INDIANA, SATURDAY, JUNE 25, 1938 5c PER COPY JAMES SWAIN Six Colored Train Prominent Doctor Celebrates 25th Year As Principal • * Employes Are Hurt Local Dentist Elected NAAGP Hoi FACES ELECTRIC In Wreck Disaster Is Honored 1 CHAIR JULY 1 Colored Porters Assisted In President of Medical Ass'n By Outpost Meet Sunda Saving Many Passengers Dr. William F. Dendy, presi lectures on surgery, diagnoses, Rev. M. R. Dixon, president James Swain, 17-year-aid lad, MILES CITY, Mont.—(ANP)— dent of the Indiana State Medi dentistry, X-Ray treatments and Dr. A. H. Wilson, vice com is to be electrocuted July 1 for mander of the local} chapter of of the local N. A. A. C- P. an! Six colored employes of the Chi cal, Dental and Pharmaceutical other subjects of a medical na nounces the regular meeting o\ the murder of Christian Breden- cago, Milwaukee and St. Paul rail Association, announces that the ture. the American Legion, was re kamp, local groceryman. Swain road suffered injuries (extent of quested by Mr. William Hyland, this organization at the Com--* fifteenth annual session of the As a grand climax to the munity Center Sunday, June 26, in company with James Alex which was not immediately de association will be held in the Commander of the local Funk- termined), last Sunday night when meet the local committee has at 5 p. m. The other officers of ander, a youth of 16 years, went Community Center Building, planned a dance to be given in houser Post of the American to Bredenkamp's Grocery, cor the Olympian, crack Milwaukee Legion, to write an article on his this organization include:»'A. -

Zustände Wie Fru¨Her Bei Schmeling

Schwa¨bische Zeitung Freitag, 19. Juni 2009 / Nr. 138 Sport Schwimmen Box-WM: Wladimir Klitschko – Chagaaev Sport am Wochenende Lurz und Maurer Boxen holen die ersten Titel WM im Schwergewicht (WBO, IBF) auf Schalke Zusta¨nde wie fru¨her bei Schmeling (Sa.): Waldimir Klitschko – Ruslan Chagaev LINDAU (sid) - Thomas Lurz (Würz- Rudern burg) und Angela Maurer (Mainz) ha- GELSENKIRCHEN (dpa) — Es ist das Haye, dem zwar eine große Klappe, Weltcup in München (bis So.) ben zum Auftakt der deutschen Meis- gro¨ßte Box-Spektakel seit Max aber auch ein Glaskinn nachgesagt Schwimmen terschaften im Freiwasserschwimmen Schmelings Zeiten: 60 000 Zuschau- wird. Haye hatte den Kampf wegen Deutsche Freiwasser-Meisterschaften in Lindau die Titel über die olympische Zehn-Ki- er in der Veltins-Arena und Millio- einer Trainingsverletzung 17 Tage vor (bis So.) lometer-Distanz gewonnen. Lurz, nen Zuschauer in mehr als 100 La¨n- dem ersten Gong abgesagt. Nach- Volleyball Bronzemedaillengewinner in Peking, dern werden die Schwergewichts- dem „Russen-Riese“ Walujew als Er- Europaliga, Gruppe B in Bremen: Deutschland – siegte nach 1:57:37,24 Stunden im weltmeisterschaft zwischen dem satzkandidat abgewunken hatte, Griechenland (Sa., 19.30/So., 16.00) 18,6 Grad warmen Bodensee vor Ukrainer Wladimir Klitschko und nahm Chagaev die Offerte Klitschkos dem letztjährigen Europacup-Gewin- dem Usbeken Ruslan Chagaev am an. ner Christian Reichert (Wiesbaden Samstag (22 Uhr/RTL) verfolgen. Wo tut sich was? :57:41,11). Beide können mit einem „Ordentlich Pru¨gel“ Ticket für die Weltmeisterschaften in Einen größeren Zuschauerauflauf Treffen der Fußballmeister in Neufra Rom (17. Juli bis 2. August) rechnen. beim Boxen hat es in Deutschland seit Als „ein Highlight“ stuft Trainer Im Waldstadion in Neufra/Donau findet mor- Titelverteidiger Toni Franz aus Leipzig 70 Jahren nicht gegeben. -

Fight Record Ben Foord (South Africa)

© www.boxinghistory.org.uk - all rights reserved This page has been brought to you by www.boxinghistory.org.uk Click on the image above to visit our site Ben Foord (South Africa) Active: 1932-1940 Weight classes fought in: Recorded fights: 58 contests (won: 40 lost: 15 drew: 3) Fight Record 1932 Jun 14 Billy Miller (South Africa) WKO3 Durban South Africa Source: Vic Hardwicke (Boxing Historian) Jul 9 Dick Manz (South Africa) WKO1 Johannesburg South Africa Source: Vic Hardwicke (Boxing Historian) Jul 23 Jack Grayling (South Africa) WKO2 Johannesburg South Africa Source: Vic Hardwicke (Boxing Historian) Aug 20 Jack Vaney (South Africa) WKO1 Brakpan South Africa Source: Vic Hardwicke (Boxing Historian) Sep 3 Johnny Squires (South Africa) LPTS(6) Johannesburg South Africa Source: Vic Hardwicke (Boxing Historian) Oct 8 Bill Horn (South Africa) WPTS(8) Johannesburg South Africa Source: Vic Hardwicke (Boxing Historian) Nov 5 Ben Ousthuizen (South Africa) WRSF2 Durban South Africa Source: Vic Hardwicke (Boxing Historian) Nov 12 Bill Horn (South Africa) DRAW(6) Johannesburg South Africa Source: Vic Hardwicke (Boxing Historian) Dec 2 Dave Carstens (South Africa) DRAW(8) Johannesburg South Africa Source: Vic Hardwicke (Boxing Historian) Dec 17 Alec Storbeck (South Africa) WKO5 Johannesburg South Africa Source: Vic Hardwicke (Boxing Historian) 1933 Feb 4 Clyde Chastain (South Africa) WPTS(10) Johannesburg South Africa Source: Vic Hardwicke (Boxing Historian) Apr 8 Clyde Chastain (South Africa) WPTS(10) Durban South Africa Source: Vic Hardwicke (Boxing Historian) May 29 Vincent Parille (Argentina) WPTS(8) Royal Albert Hall, Kensington Source: Boxing 31/05/1933 page 8 Jul 12 Charlie Smith (Deptford) WPTS(10) Stadium, White City Source: Boxing 19/07/1933 page 7 Referee: Patsy Fox Oct 23 Tom Tucker (Bamber Bridge) WRSF1(12) Crystal Palace, Sydenham Source: Boxing 24/10/1933 page 16 Tucker was Northern Area Heavyweight Champion 1929. -

Jänner Zeitung Ausgabe Inhalt SVB 2.1.1942, S.4

Jänner Zeitung Ausgabe Inhalt SVB 2.1.1942, S.4 Weltmeister Bradl fand in Steinbach am Neujahrstage mit Hans Marx (Thüringen) einen ernsthaften Gegner; Gleichheit der beiden; Inoffizieller Schanzenrekord von Bradl am Vortag; Eishockey: Stockholm schlug Riessersee 2:0; Fußball: Schweiz verlor gegen Portugal in Lissabon mit 3:0 und gegen Spanien mit 2:3; Berlin schlug Krakauer Stadtmannschaft mit 3:1; 3.1.1942, S.6 Die Absage der diesjährigen Skilauf- Veranstaltungen; Amtliche Verfügung des Reichsportführers hatte folgenden Wortlaut: Skier und Skigeräte sind an die Wehrmacht abzugeben, Alle Veranstaltungen werden abgesagt. HJ-betreffend werden von der Reichsjugendführung bekanntgegeben; Hans Hintermeier: bestieg die Westwand der Großen Zinne; 4-20.1.fehlen! 21.1.1942 23.1.1942, S.5 Erstdurchkletterung im Winter: Uitz und Faistauer auf die direkte Südwand des Vorderen Fieberhorns; Eislauf des BSDM an Stelle des Skilaufes: Eislauf statt Skier; Friedl Matschl mit Kursen; Tischtennis-Meisterschaften der RSG Salzburg wurde beendet; Wegrostek siegte im Einzel; Wegrostek und Ablinger gewannen das Doppel; 24.1.1942, S.8 DAF-Sportgautagung der Orts-und Betriebssportwarte und Übungswarte des Sportamtes der NS-Gemeinschaft Kraft durch Freude; Resch und Stegemann sprechen; Reichsiegerwettbewerb der HJ im Eisschnelllauf am Zeller See: Westdeutscher Doppelerfolg; Rudi Geuer und Helmut Winter siegten; Kunstlauf-Gaumeisterschaften ist der Eislaufplatz in Nonntal heute geschlossen; Salzburger Eisschützen im Markt Pongau zu Gast; Pongauer siegten 2:0; Tischtennis-Vergleichskampf: -

![1934-10-03 [P A-16]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3122/1934-10-03-p-a-16-4503122.webp)

1934-10-03 [P A-16]

Lasky and Hamas Will Trade Punches for Shot at Baer AGGRESSIVE ART Struts Mat Stuff Tomorrow DOGS They “Were Off” at Laurel Yesterday FAVOREDJO WIN Offer to ***** Spurns $35,000 Races, Fashion Show and 'Meet Schmeling Rather Dance to Mark Dedication exceptional Than Leave U. S. of Parkway October 27. cigars BY SPARROW McGAXX. COMMEMORATE the exten- YORK, October 3 — Art sion of bridle paths and park- Lasky and Steve Hamas TO ways from the District of Co- NEWsignal the opening of the lumbia into .Maryland along indoor boxing season at Rock Creek, the Maryland Parkway ***** Madison Square Garden Friday Meadow brook horse and hound show evening with the avowed intention and races will be held October 27 at distinctive of earning the right to meet Cham- the new horse show grounds south of the out- pion Max Baer. They are the Meadowbrook Riding Academy on flavors standing heavyweight contenders and the East-West highway. the winner will be conceded an edge Plans for the show were outlined others who have designs on the today by officials of the Maryland- over BOB (BIBBER) McCOY, Californian s crown. Naiional Capital Park and Planning Bold Bostonian and New England heavyweight favorite, who tackles Steve still is in the field, who are the Max Schmeling Znoski in prelim to the Marshall-Shikat feature of Promoter Joe Turner's Commission, building at the hands of despite a setback first indoor show of the season at the Auditorium. grounds as part of the park develop- o** last February. The Steve Hamas ment in Montgomery County. -

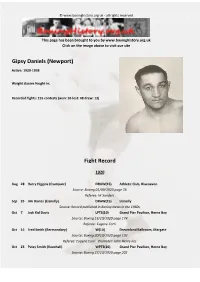

Fight Record Gipsy Daniels (Newport)

© www.boxinghistory.org.uk - all rights reserved This page has been brought to you by www.boxinghistory.org.uk Click on the image above to visit our site Gipsy Daniels (Newport) Active: 1920-1938 Weight classes fought in: Recorded fights: 155 contests (won: 95 lost: 48 drew: 12) Fight Record 1920 Aug 28 Harry Higgins (Cwmparc) DRAW(15) Athletic Club, Blaenavon Source: Boxing 01/09/1920 page 78 Referee: W Sanders Sep 25 Jim Davies (Llanelly) DRAW(15) Llanelly Source: Record published in Boxing News in the 1960s Oct 7 Jack Kid Davis LPTS(10) Grand Pier Pavilion, Herne Bay Source: Boxing 13/10/1920 page 174 Referee: Eugene Corri Oct 16 Fred Smith (Bermondsey) W(10) Dreamland Ballroom, Margate Source: Boxing 20/10/1920 page 192 Referee: Eugene Corri Promoter: John Henry Iles Oct 23 Patsy Smith (Vauxhall) WPTS(10) Grand Pier Pavilion, Herne Bay Source: Boxing 27/10/1920 page 202 Oct 30 Bill Johnson (Drury Lane) WKO3(10) Dreamland Ballroom, Margate Source: Boxing 03/11/1920 page 222 Referee: Eugene Corri Nov 15 Harry Franks (Hackney) WPTS(15) Skating Rink, Clapton Source: Boxing 17/11/1920 page 249 Referee: HW Keen Nov 26 Joe Davis (Hoxton) WPTS(10) Royal Albert Hall, Kensington Source: Boxing 01/12/1920 pages 288 and 289 Referee: HW Keen 1921 Feb 24 Rene DeVos (Belgium) LPTS(20) The Ring, Blackfriars Source: Boxing 02/03/1921 page 42 Match made at 11st 6lbs Referee: Ted Broadribb Apr 2 Ivor Powell (New Tredegar) WRTD5(15) Drill Hall, Pontypool Source: Boxing 06/04/1921 pages 125 and 126 Promoter: D W Davies(Blaenavon) Apr 5 Eddie Feathers