A Case Study of Bhoje Landslide, Lamjung, Nepal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nutritional Status and Social Influences in Dalit and Brahmin Women and Children in Lamjung Using Mixed Methods

Nutritional status and social influences in Dalit and Brahmin women and children in Lamjung using mixed methods A. Objective and Specific Aims Objective: - To measure nutritional status, of women (18-44 years) and children under five (6-59 months), of Dalit and Brahmins by taking anthropometric measures in Lamjung district, Western Nepal - To conduct structured surveys and qualitative assessments of how underlying social and behavioral factors, e.g. availability, access and utilization of food, and childcare, influence nutritional status of Dalit and Brahmin women and their children Specific Aims: - To obtain the anthropometric measurements of height, weight and upper arm circumference to determine indicators of nutritional status including underweight, stunting and wasting among children under five; and to determine body mass index (BMI) among their mothers and stepmothers (if living in a same household) - To administer structured surveys to obtain household and socio-demographic information such as number of offspring and co-wives, caste status (Dalits or Brahmins), age of women and children, socio-economic status (SES) and food insecurity information - To conduct in-depth interviews of a subsample of Dalit and Brahmin women to understand how socio-cultural aspects in their lives affect food insecurity B. Background and significance It can be hypothesized that in Nepal, the social status of Dalit women– a collection of the untouchable castes – could contribute to having a lower nutritional status of themselves and their children, compared to maternal and child malnutrition among Brahmin castes (the highest ranked caste) residing in the same villages. This association between social status and malnutrition has been consistently found in developing nations (Gurung, 2010). -

Ibn 32Nd Board Meeting 3

IBN DISPATCH | YEAR: 3 | ISSUE: 10 | VOLUME: 34 | ASOJ 2075 (SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER 2018) 1 MONTHLY E-NEWSLETTER OF OIBN IBN DISPATCH YEAR: 3 | ISSUE: 10 | VOLUME: 34 | ASOJ 2075 (SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER 2018) IBN 32ND BOARD MEETING 3 HONGSHI ACHIEVES FINANCIAL CLOSURE 4 INTERACTION WITH GOVERNMENT OF 5 KARNALI PROVINCE GMR TO SIGN PPA WITH BANGLADESH SOON 9 OIBN INITIATES INTERACTIONS TO 10 FINALIZE KEY PROJECTS IN PROVINCES OICES 6 MOU SIGNED FOR CABLE CAR 11 OF PEOPLE’S REPRESENTATIVES 2 IBN DISPATCH | YEAR: 3 | ISSUE: 10 | VOLUME: 34 | ASOJ 2075 (SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER 2018) INVESTO GRAPH INVESTMENT COMMITMENTS THROUGH IBN Since establishment of IBN (US Dollars in Million) 2.4 200 TOTAL COMMITMENTS Industry: Solar Power Industry: Solid Waste Mgmt. Project: Dolma Fund Management Project: Dharan Waste to Energy Country: Nepal Country: Nepal Year: 2018 Year: 2017 140 5550 140 Industry: Hotel Industry: Cement Project: Japan Club International Project: Huaxin Country: Japan ENERGY Country: China Year: 2018 Year: 2015 369 Industry: Cement 4000 Project: Hongshivam Country: China Year: 2015 1600 Industry: Hydropower CEMENT Project: West Seti 400 Country: China Industry: Cement Year: 2015 Project: Reliance 1160 Country: India Year: 2014 Industry: Hydropower Project: Upper Karnali 1459 Country: India Year: 2014 550 1040 HOTEL Industry: Cement Industry: Hydropower Project: Dangote Project: Arun-3 Country: Nigeria Country: India 140 Year: 2013 Year: 2014 8 49 Industry: Solid Waste Mgmt. Project: KTM Solid Waste Mgmt. Industry: Solid Waste Mgmt. SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT (Package-II&III) Project: KTM Solid Waste Mgmt. Country: India+Nepal (Package-I) Year: 2014 Country: Finland+Nepal $Year: 2014 59 IBN DISPATCH | YEAR: 3 | ISSUE: 10 | VOLUME: 34 | ASOJ 2075 (SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER 2018) 3 IBN 32ND MEETING HELD 5550 KATHMANDU: The 32nd meeting of the Invest- expressed an unwillingness to develop the project. -

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

Women's Agency in Relation to Population and Environment in Rural

Women’s Agency in Relation to Population and Environment in Rural Nepal Narayani Tiwari Promotor Prof. Dr. A. Niehof Hoogleraar Sociologie van Consumenten en Huishoudens Co-promotor Dr. L.L. Price Universitair hoofddocent leerstoelgroep Sociologie van Consumenten en Huishoudens Promotiecommissie Prof. Dr. L.E. Visser Wageningen Universiteit Prof. Dr. I. Hutter Rijksuniversiteit Groningen Prof. Dr. D.R. Dahal Tri-bhuvan University, Kathmandu, Nepal Dr. Ir. M.Z. Zwarteveen Wageningen Universiteit Dit onderzoek is uitgevoerd binnen de onderzoeksschool Mansholt Graduate School of Social Science Women’s Agency in Relation to Population and Environment in Rural Nepal Narayani Tiwari Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor op gezag van de rector magnificus van Wageningen Universiteit, Prof. Dr. M.J. Kropff, in het openbaar te verdedigen op donderdag 4 oktober 2007, des ochtends om 11.00 uur in de Aula Women’s agency in relation to population and environment in rural Nepal / Narayani Tiwari. PhD Thesis, Wageningen University (2007). With references – With summaries in English and Dutch ISBN 978-90-8504-696-7 Subject headings: women, agency, population, environment, livelihood, food security, Gurung, Nepal. Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to the institutions and individuals who contributed to the successful completion of this research. I would like to thank Wageningen University and Research Centre (WUR) for granting me a Sandwich PhD fellowship that enabled me to embark on the PhD track. I would also like to acknowledge the generous financial support of the Neys-Van Hoogstraten Foundation (NHF) for the fieldwork and the thesis editing. Without the support of NHF the research could not have been carried out. -

ESMF – Appendix

Improving Climate Resilience of Vulnerable Communities and Ecosystems in the Gandaki River Basin, Nepal Annex 6 (b): Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) - Appendix 30 March 2020 Improving Climate Resilience of Vulnerable Communities and Ecosystems in the Gandaki River Basin, Nepal Appendix Appendix 1: ESMS Screening Report - Improving Climate Resilience of Vulnerable Communities and Ecosystems in the Gandaki River Basin Appendix 2: Rapid social baseline analysis – sample template outline Appendix 3: ESMS Screening questionnaire – template for screening of sub-projects Appendix 4: Procedures for accidental discovery of cultural resources (Chance find) Appendix 5: Stakeholder Consultation and Engagement Plan Appendix 6: Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) - Guidance Note Appendix 7: Social Impact Assessment (SIA) - Guidance Note Appendix 8: Developing and Monitoring an Environmental and Social Management Plan (ESMP) - Guidance Note Appendix 9: Pest Management Planning and Outline Pest Management Plan - Guidance Note Appendix 10: References Annex 6 (b): Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) 2 Appendix 1 ESMS Questionnaire & Screening Report – completed for GCF Funding Proposal Project Data The fields below are completed by the project proponent Project Title: Improving Climate Resilience of Vulnerable Communities and Ecosystems in the Gandaki River Basin Project proponent: IUCN Executing agency: IUCN in partnership with the Department of Soil Conservation and Watershed Management (Nepal) and -

Nepal's Constitution (Ii): the Expanding

NEPAL’S CONSTITUTION (II): THE EXPANDING POLITICAL MATRIX Asia Report N°234 – 27 August 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. THE REVOLUTIONARY SPLIT ................................................................................... 3 A. GROWING APART ......................................................................................................................... 5 B. THE END OF THE MAOIST ARMY .................................................................................................. 7 C. THE NEW MAOIST PARTY ............................................................................................................ 8 1. Short-term strategy ....................................................................................................................... 8 2. Organisation and strength .......................................................................................................... 10 3. The new party’s players ............................................................................................................. 11 D. REBUILDING THE ESTABLISHMENT PARTY ................................................................................. 12 1. Strategy and organisation .......................................................................................................... -

Climate Change Project Implementation in Lamjung

Climate Change Project Implementation in Lamjung: A Case of Hariyo Ban Project Dil B. Khatri Tikeshwari Joshi Bikash Adhikari Adam Pain CCRI case study 3 Climate Change Project Implementation in Lamjung: A Case of Hariyo Ban Project Dil B. Khatri, ForestAction Nepal Tikeshwari Joshi, Southasia Institute of Advanced Studies Bikash Adhikari, ForestAction Nepal Adam Pain, Danish Institute for International Studies Climate Change and Rural Institutions Research Project In collaboration with: Copyright © 2015 ForestAction Nepal Southasia Institute of Advanced Studies Published by ForestAction Nepal PO Box 12207, Kathmandu, Nepal Southasia Institute of Advanced Studies Baneshwor, Kathmandu, Nepal Photos: Bikash Adhikari Design and Layout: Sanjeeb Bir Bajracharya Suggested Citation: Khatri, D.B., Joshi, T., Adhikari, B. and Pain, A. 2015. Climate change project implementation in Lamjung: A case of Hariyo Ban Project. Case Study Report 3. Kathmandu: ForestAction Nepal and Southasia Institute of Advance Studies. The views expressed in this discussion paper are entirely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of ForestAction Nepal and SIAS. Table of Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 1 2. Socio-economic and disaster context of Lamjung district ....................................................... 2 3. Hariyo Ban project: problem framing and project design ...................................................... -

Vaccines from Bahrain, Which Are Under Probe, Are Chinese, Officials

WITHOUT F EAR OR FAVOUR Nepal’s largest selling English daily Vol XXIX No. 29 | 12 pages | Rs.5 O O Printed simultaneously in Kathmandu, Biratnagar, Bharatpur and Nepalgunj 34.4 C 2.5 C Friday, March 19, 2021 | 06-12-2077 Nepalgunj Jumla Vaccines from Bahrain, which are under probe, are Chinese, officials say Nepal’s drug regulator says it is consulting with foreign and health ministries, as the issue is not just technical but also concerns bilateral ties and diplomacy. ARJUN POUDEL Sinopharm’s BBIBP-CorV but not to KATHMANDU, MARCH 18 Sinovac’s CoronaVac. Nepal, however, has not rolled out A report on an investigation into Sinopharm vaccines yet. The Oxford- how 2,000 doses of Covid-19 vaccine AstraZeneca vaccine was the first to were brought to Nepal by a Bahraini get emergency use authorisation in prince was to be submitted on Nepal. The vaccine, manufactured by Thursday evening. the Serum Institute of India under the But officials on Thursday afternoon brand name of Covishield, is current- said that the vaccines were Chinese, ly being used in Nepal. not AstraZeneca as claimed before. Sheikh Mohamed Hamad Mohamed At least two officials at the Health al-Khalifa, the Bahraini prince, and Ministry, who did not wish to be his team landed in Kathmandu on named, said that the vaccines from Monday on an Everest mission. Bahrain are Chinese and developed The Nepali embassy in Bahrain on by Sinovac Biotech, for which Nepal Monday said in a statement that the has not granted emergency use prince’s team would be carrying 2,000 authorisation. -

ZSL National Red List of Nepal's Birds Volume 5

The Status of Nepal's Birds: The National Red List Series Volume 5 Published by: The Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London, NW1 4RY, UK Copyright: ©Zoological Society of London and Contributors 2016. All Rights reserved. The use and reproduction of any part of this publication is welcomed for non-commercial purposes only, provided that the source is acknowledged. ISBN: 978-0-900881-75-6 Citation: Inskipp C., Baral H. S., Phuyal S., Bhatt T. R., Khatiwada M., Inskipp, T, Khatiwada A., Gurung S., Singh P. B., Murray L., Poudyal L. and Amin R. (2016) The status of Nepal's Birds: The national red list series. Zoological Society of London, UK. Keywords: Nepal, biodiversity, threatened species, conservation, birds, Red List. Front Cover Back Cover Otus bakkamoena Aceros nipalensis A pair of Collared Scops Owls; owls are A pair of Rufous-necked Hornbills; species highly threatened especially by persecution Hodgson first described for science Raj Man Singh / Brian Hodgson and sadly now extinct in Nepal. Raj Man Singh / Brian Hodgson The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of participating organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of any participating organizations. Notes on front and back cover design: The watercolours reproduced on the covers and within this book are taken from the notebooks of Brian Houghton Hodgson (1800-1894). -

Strengthening the Role of Civil Society and Women in Democracy And

HARIYO BAN PROGRAM Monitoring and Evaluation Plan 25 November 2011 – 25 August 2016 (Cooperative Agreement No: AID-367-A-11-00003) Submitted to: UNITED STATES AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT NEPAL MISSION Maharajgunj, Kathmandu, Nepal Submitted by: WWF in partnership with CARE, FECOFUN and NTNC P.O. Box 7660, Baluwatar, Kathmandu, Nepal First approved on April 18, 2013 Updated and approved on January 5, 2015 Updated and approved on July 31, 2015 Updated and approved on August 31, 2015 Updated and approved on January 19, 2016 January 19, 2016 Ms. Judy Oglethorpe Chief of Party, Hariyo Ban Program WWF Nepal Baluwatar, Kathmandu Subject: Approval for revised M&E Plan for the Hariyo Ban Program Reference: Cooperative Agreement # 367-A-11-00003 Dear Judy, This letter is in response to the updated Monitoring and Evaluation Plan (M&E Plan) for the Hariyo Program that you submitted to me on January 14, 2016. I would like to thank WWF and all consortium partners (CARE, NTNC, and FECOFUN) for submitting the updated M&E Plan. The revised M&E Plan is consistent with the approved Annual Work Plan and the Program Description of the Cooperative Agreement (CA). This updated M&E has added/revised/updated targets to systematically align additional earthquake recovery funding added into the award through 8th modification of Hariyo Ban award to WWF to address very unexpected and burning issues, primarily in four Hariyo Ban program districts (Gorkha, Dhading, Rasuwa and Nuwakot) and partly in other districts, due to recent earthquake and associated climatic/environmental challenges. This updated M&E Plan, including its added/revised/updated indicators and targets, will have very good programmatic meaning for the program’s overall performance monitoring process in the future. -

Nepali Times on Facebook Printed at Jagadamba Press | 01-5250017-19 | Follow @Nepalitimes on Twitter 8 - 14 JUNE 2012 #608 OP-ED 3

#608 8 - 14 June 2012 16 pages Rs 30 Hot spot here are two types of carbon that cause Himalayan snows to Tmelt. One is carbon dioxide from fossil fuel burning that heats up the atmosphere through the greenhouse- effect. The other is tiny particles of solid carbon given off by smokestacks and diesel exhausts that are deposited on snow and ice and cause them to melt faster. Both contribute to the accelerated meltdown of the Himalaya. Yak herders below Ama Dablam (right) now cross grassy meadows where there used to be a glacier 40 years ago. Nepal’s delegation at the Rio+20 Summit in Brazil later this month will be arguing that the country cannot sacrifi ce economic growth to save the environment. Increasingly, that is looking like an excuse to not address pollution in our own backyard. Full story by Bhrikuti Rai page 12-13 NO WATER? NO POWER? NO PROBLEM How to live without electricity and water page 5 Mother country Federalism and governance were not the only contentious issues in the draft constitution that was not passed on 27 May. Provisions on citizenship were even more regressive than in the interim constitution. There is now time to set it right. EDITORIAL page 2 OP-ED by George Varughese and Pema Abrahams page 3 BIKRAM RAI 2 EDITORIAL 8 - 14 JUNE 2012 #608 MOTHER COUNTRY Only the Taliban treats women worse hen the Constituent Assembly expired two 27 May. Our “progressive” politicians were too busy weeks ago, there was disappointment but haggling over state structure and forms of governance to Walso relief at having put off a decision on notice. -

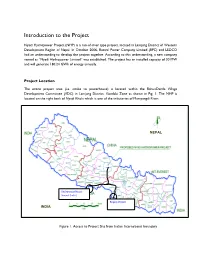

Introduction to the Project

Introduction to the Project Nyadi Hydropower Project (NHP) is a run-of-river type project, located in Lamjung District of Western Development Region of Nepal. In October 2006, Butwal Power Company Limited (BPC) and LEDCO had an understanding to develop the project together. According to this understanding, a new company named as “Nyadi Hydropower Limited” was established. The project has an installed capacity of 30 MW and will generate 180.24 GWh of energy annually. Project Location The entire project area (i.e. intake to powerhouse) is located within the BahunDanda Village Development Committee (VDC) in Lamjung District, Gandaki Zone as shown in Fig. 1. The NHP is located on the right bank of Nyadi Khola which is one of the tributaries of Marsyangdi River. NEPAL Bhairahawa (Nepal) Sunauli (India) Birganj (Nepal) INDIA Raxaul (India) Figure 1. Access to Project Site from Indian International boundary Fig. 2. Project location in Lamjung Access to Project site: The nearest road head to project site from district headquarter of Lamjung; Besisahar is located at Thakenbesi 22 km gravel road of Besisahar-Chame road. Road upto district headquarter Besisahar is blacktop. Besisahar is 185 km west from the Kathmandu and reach by the prithivi highway up to Dumre and Besisahar is 45 km from Dumre. Nearest Road head from Project Site be reached in following ways from the different parts of the Country. Technical Features of the Project Nyadi Hydropower Project is a run-of-the-river type project. The proposed system of the power plant will be run for its full capacity of 30 MW for about 5 months of the year.