The Gospel in the Stars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strategies of Defending Astrology: a Continuing Tradition

Strategies of Defending Astrology: A Continuing Tradition by Teri Gee A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology University of Toronto © Copyright by Teri Gee (2012) Strategies of Defending Astrology: A Continuing Tradition Teri Gee Doctorate of Philosophy Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology University of Toronto 2012 Abstract Astrology is a science which has had an uncertain status throughout its history, from its beginnings in Greco-Roman Antiquity to the medieval Islamic world and Christian Europe which led to frequent debates about its validity and what kind of a place it should have, if any, in various cultures. Written in the second century A.D., Ptolemy’s Tetrabiblos is not the earliest surviving text on astrology. However, the complex defense given in the Tetrabiblos will be treated as an important starting point because it changed the way astrology would be justified in Christian and Muslim works and the influence Ptolemy’s presentation had on later works represents a continuation of the method introduced in the Tetrabiblos. Abû Ma‘shar’s Kitâb al- Madkhal al-kabîr ilâ ‘ilm ahk. âm al-nujûm, written in the ninth century, was the most thorough surviving defense from the Islamic world. Roger Bacon’s Opus maius, although not focused solely on advocating astrology, nevertheless, does contain a significant defense which has definite links to the works of both Abû Ma‘shar and Ptolemy. As such, he demonstrates another stage in the development of astrology. -

Helios Megistos: Zur Synkretistischen Theologie Der Spdtantike

RELIGIONS IN THE GRAECO-ROMAN WORLD EDITORS R. VAN DEN BROEK H.J.W. DRIJVERS H.S. VERSNEL VOLUME 125 HELIOS MEGISTOS %ur synkretistischen Theologie der Spätantike VON WOLFGANG FAUTH EJ. BRILL LEIDEN · NEW YORK · KÖLN 1995 Thu series Religions in the Graeco-Roman World presents a forum for studies in the social and cultural function of religions in the Greek and the Roman world, dealing with pagan religions both in their own right and in their interaction with and influence on Christianity and Judaum during a lengthy period of fundamental change. Special attention will be given to the religious history of regions and cities which illustrate the practical workings of these processes. Enquiries regarding the submission of works for publication in the series may be directed to Professor H.J.W. Drijvers, Faculty of letters, University of Groningen, 9712 ΕΚ Groningen, The Netherlands. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Fauth, Wolfgang. Helios megistos : zur synkretistischen Theologie der Spätantike / von VV. Fauth. p. cm. (Religions in the Graeco-Roman world. ISSN 0927-7633 ; v. 125) Includes index. ISBN 9004101942 (cloth : alk. paper} 1. Helios (Greek deitv) I. Title. II. Series. BL820.S62F38 1995' 292. Γ2113--de 20 94-38391 CIP Die Deutsche Bibliothek - CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Fauth, Wolfgang: Helios megistos : zur synkretistischen Theologie der Spätantike / von W.'Fauth. Leiden ; New York ; Köln : Brill, 1995 (Religions in the Graeco-Roman world ; Vol. 125) ISBN 90-04-10194-2 NE: G Γ ISSN 0927-7633 ISBN 90 04 10194 2 © Copyright 1995 by K.J. -

Preložené Ako Inšpirácia Pre Tých, Ktorí Hľadajú Odpovede V Chaose a Despovláde Parazitov

Preložené ako inšpirácia pre tých, ktorí hľadajú odpovede v chaose a despovláde parazitov. http://chronologia.org/en/how_it_was/index.html А.Т. Фоменко - Как было на самом деле. Каждая история желает быть рассказанной 1 / 423 Table of Contents Predslov..............................................................................................................................................10 1. Všeobecne prijatá verzia svetovej histórie bola vytvorená len v xvii storočí. Bola upravovaná až do 19. Storočia - táto verzia je nesprávna.................................................................................10 2. Psychologické poznámky..........................................................................................................16 Epocha pred xi. Storočím...................................................................................................................17 Kapitola 1. Epoch xi. storočia............................................................................................................19 1. Prvé románske kráľovstvo starého Rímu...................................................................................19 2. Astronomické záznamy novej chronológie................................................................................20 Kapitola 2. Epocha xii. storočia.........................................................................................................22 1. Druhý Rím alebo rímska cár-grad ríša. Yoros = Jeruzalem = Trója..........................................22 2. Narodenie krista -

Cosmological Narrative in the Synagogues of Late Roman-Byzantine Palestine

COSMOLOGICAL NARRATIVE IN THE SYNAGOGUES OF LATE ROMAN-BYZANTINE PALESTINE Bradley Charles Erickson A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Religious Studies. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Jodi Magness Zlatko Plese David Lambert Jennifer Gates-Foster Maurizio Forte © 2020 Bradley Charles Erickson ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Bradley Charles Erickson: Cosmological Narrative in the Synagogues of Late Roman-Byzantine Palestine (Under the Direction of Jodi Magness) The night sky provided ancient peoples with a visible framework through which they could view and experience the divine. Ancient astronomers looked to the night sky for practical reasons, such as the construction of calendars by which time could evenly be divided, and for prognosis, such as the foretelling of future events based on the movements of the planets and stars. While scholars have written much about the Greco-Roman understanding of the night sky, few studies exist that examine Jewish cosmological thought in relation to the appearance of the Late Roman-Byzantine synagogue Helios-zodiac cycle. This dissertation surveys the ways that ancient Jews experienced the night sky, including literature of the Second Temple (sixth century BCE – 70 CE), rabbinic and mystical writings, and Helios-zodiac cycles in synagogues of ancient Palestine. I argue that Judaism joined an evolving Greco-Roman cosmology with ancient Jewish traditions as a means of producing knowledge of the earthly and heavenly realms. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my sincere appreciation to my adviser, Dr. -

Excavating the Puzzle of the Paris Zodiac

NATURE|Vol 465|3 June 2010 OPINION billion as problem solvers. People are a country’s infrastructure in poor countries did not come The supply of aid or a reliance on centralized biggest natural asset, and their engagement from state mineral wealth. Instead, individuals’ mineral wealth destroys or prevents this link can bring about economic progress. Nearly ability to pay, stemming from their increased from emerging. two decades ago, I started an effort to pro- productivity, attracted investment. Entrepre- The Plundered Planet is right to highlight vide widely accessible mobile-phone serv- neurs capitalized on this opportunity to provide the importance of government accountability ices in Bangladesh, leading to the creation of a service. As economist Joseph Schumpeter in addressing poverty and climate change. But it the company Grameenphone. A competitive noted in the 1930s, entrepreneurs — armed will be the dispersion of power, fuelled by entre- multibillion-dollar telecommunications indus- with ideas but not necessarily money — can preneurship and innovation, that will ultimately try has since grown up there, based simply on rearrange the means of production to boost empower individuals to create accountability products and services that increase people’s economic growth. In other words, empowered and solve global problems. ■ productivity and income. In parallel, mobile- by tools and schemes that enhance productiv- Iqbal Quadir is professor of the practice phone technology has attracted billions of ity, the poor can tackle problems without rely- of development and entrepreneurship and dollars in investment to other countries that ing on coordinated efforts by governments. founder and director of the Legatum Center lack drinking water, health care and electricity, It is a virtuous cycle: citizens advance their at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, such as in sub-Saharan Africa. -

Decoding the Last Supper

HOUSE OF TRUTH | TOTUUDEN TALO Decoding the Last Supper The Great Year and Men as Gods House of Truth | www.houseoftruth.education 21.6.2013 Table of Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................... 2 The Last Supper and the Great Year .................................................................................................................. 3 36 engravings on the roof ............................................................................................................................. 4 Elements of the Last Supper .......................................................................................................................... 5 Hands of Christ .............................................................................................................................................. 6 The Lesser Conclusion ................................................................................................................................... 7 Men as Gods in the Last Supper ........................................................................................................................ 8 Roman trio of gods ........................................................................................................................................ 9 Evidence number 153 ................................................................................................................................. -

Hindu Astronomy

HINDU ASTRONOMY BY W. BRENNAND, WITH THIRTEEN ILLUSTRATIONS AND NUMEROUS DIAGRAMS. London : Published by Chas. Straker & Sons, Ltd., Bishopsgate Avenue, E.C. 1896. S JUL 3 1 1974 fysm OF Wf B-7M Printed by Chas. Straker & Sons, Ltd., BisiiorsoATE Avenue, London, E.G. PREFACE. It is perhaps expected that some reason should be given for tho publication of this work, though it may appear inadequate. Force of circumstances; rather than deliberate choice on my part, impelled it now that it has been I cannot but feel how ; and, accomplished, imperfect the production is. A lengthened residence in India led me to become interested in the study of the ancient mathematical works of the Hindus. This study was frequently interrupted by official duties, and much information acquired in its course lias been for a time forgotten. Recent circumstances, and chiefly the interest displayed by my former pupils in a paper presented to the Royal Society on the same subject, has induced me to make an effort to regain the lost ground, and to gather together materials for a more extended work. Moreover, a conviction formed many years ago that the Hindus have not received the credit due to their literature and mathematical science from Europeans, and which has been strengthened by a renewal of my study of those materials, has led me also to a desire to put before the public their system of astronomy in as simple a maimer as possible, with the object of enabling those interested in the matter to form their own judgment upon it, and, possibly, to extend further investigations in the subject. -

Heraldry As Art : an Account of Its Development and Practice, Chiefly In

H ctwWb gc M. L. 929.6 Ev2h 1600718 f% REYNOLDS HISTORICAL GENEALOGY COLLECTION ALLEN COUNTY PUBLIC LIBRARY 3 1833 00663 0880 HERALDRY AS ART HERALDRY AS ART AN ACCOVNT OF ITS DEVELOPMENT AND PRACTICE CHIEFLY IN ENGLAND BY G W. EVE BTBATSFORD, 94 HIGH HOLBORN LONDON I907 Bctlkr & Tanner, The Selwood Printing ^Vobks, Frome, and London. 1GC0718 P r e fa c e THE intention of this book is to assist the workers in the many arts that are concerned with heraldry, in varying degrees, by putting before them as simply as possible the essential principles of heraldic art. In this way it is hoped to contribute to the improve- ment in the treatment of heraldry that is already evident, as a result of the renewed recognition of its ornamental and historic importance, but which still leaves so much to be desired. It is hoped that not only artists but also those who are, or may become, interested in this attractive subject in other ways, will find herein some helpful information and direction. So that the work of the artist and the judgment and appreciation of the public may alike be furthered by a knowledge of the factors that go to make up heraldic design and of the technique of various methods of carrying it into execution. To this end the illustrations have been selected from a wide range of subjects and concise descriptions of the various processes have been included. And although the scope of the book cannot include all the methods of applying heraldry, in Bookbinding, Pottery and Tiles for example, the principles that are set forth will serve ;; VI PREFACE all designers who properly consider the capabilities and limitations of their materials. -

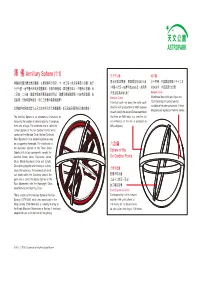

Armillary Sphere (1:1)

ìMň Armillary Sphere (1:1) P7 GɌ Ɍ ìň͈éƼP͵˲ɗňˢľ:C?·XZ#Z9YŹXŹ·:ň%P ˊ9˥ɚƮoŅ=ϝŋ@365¼̑ 8oXƷ=ŋV°PVLc 7 GɌZɌůPʂčͦɌ:5o+βϏľŶƙ˲dz͔\#Ź·Yēň% #ɍD(ƙE ł-·365¼̀ɰŲ S9Ʒ=ŋ?ϟ LɌZL?ɌZͥ˛čͦɌůǩͦɌľ`5̌͵Cūɫƭ˛ƕ9Ź·Vͥň% PRȓƙ·365¼̑ Horizon Circle A horizontal ring with 4 wei, 8 gan and VͥoZPƭů͛Ͳ5CYēň9ūɫƭ˛ƕ Meridian Circle A vertical split ring along the north-south 12 zhi (totalling 24 cardinal points) Fìň͈ȴʙˊĭŁʔP~RɗǺ(=7ìňɒçĦµ̮ʌ"dzGÓɗȜ̑ direction with graduations of 365¼ degrees inscribed on the outer surface and 12 fenye on each side (As the ancient Chinese determined (kingdoms and regions) on the inner surface The Armillary Sphere is an astronomical instrument for that there are 365¼ days in a year, the full measuring the position of celestial objects. It comprises circumference of the sky is assigned as three sets of rings. The outermost one is called the 365¼ degrees) Liuheyi (Sphere of the Six Cardinal Points) which consists of the Meridian Circle, Horizon Circle and Fixed Equatorial Circle welded together securely on a supporting framework. The middle one is :ň the Sanchenyi (Sphere of the Three Stellar Objects) with its four components, namely, the Sphere of the Solstitial Colure Circle, Equinoctial Colure Six Cardinal Points Circle, Mobile Equatorial Circle and Ecliptic Circle joining together and rotating as a whole PʂčͦɌ around the polar axis. The innermost set which can rotate within the Sanchenyi around the .P̸čͦ polar axis is called the Siyouyi (Sphere of the \ŋVLòēEWŋ Four Movements) with the Hour-angle Circle, ̀XWŋo Celestial Axis and Sighting Tube. -

Right Ascension - Wikipedia

12/2/2018 Right ascension - Wikipedia Right ascension Right ascension (abbreviated RA; symbol α) is the angular distance measured eastward along the celestial equator from the Sun at the March equinox to the hour circle of the point above the earth in question.[1] When paired with declination, these astronomical coordinates specify the direction of a point on the celestial sphere (traditionally called in English the skies or the sky) in the equatorial coordinate system. An old term, right ascension (Latin: ascensio recta[2]) refers to the ascension, or the point on the celestial equator that rises with any celestial object as seen from Earth's equator, where the celestial equator intersects the horizon at a right angle. It contrasts with oblique ascension, the point on the celestial equator that rises with any celestial object as seen from most latitudes on Earth, where the celestial equator intersects the horizon at an oblique angle.[3] Contents Explanation Symbols and abbreviations Effects of precession History See also Right ascension and declination as seen on the Notes and references inside of the celestial sphere. The primary direction External links of the system is the March equinox, the ascending node of the ecliptic (red) on the celestial equator (blue). Right ascension is measured eastward up to 24h along the celestial equator from the primary Explanation direction. Right ascension is the celestial equivalent of terrestrial longitude. Both right ascension and longitude measure an angle from a primary direction (a zero point) on an equator. Right ascension is measured from the sun at the March equinox i.e. -

Commemorative Medals

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ COMMEMORATIVE MEDALS BRITISH HISTORICAL MEDALS 1001 1002 1001 Mary, Queen of Scots, Gilt-silver Counter, 1579, crowned shield dividing arms of France and Scotland, rev a vine with one branch flourishing in the rain and one withering, MEA SIC MIHI PROSVNT, 28mm (MI 129.80). Very fine or nearly so, the gilding contemporary, very rare. £450-500 1002 Alliance of England, France and the United Provinces, Silver Jeton, 1596, struck in Dordrecht, Belgic Lion to left, with sword and arrows, SC below, rev hand -

MEDALLIC HISTORY of RELIGIOUS and RACIAL INTOLERANCE: MEDALS AS INSTRUMENTS for PROMOTING BIGOTRY by Benjamin Weiss

MEDALLIC HISTORY OF RELIGIOUS AND RACIAL INTOLERANCE: MEDALS AS INSTRUMENTS FOR PROMOTING BIGOTRY by Benjamin Weiss ABSTRACT Prejudices of all types represent a profound failure and blight on our society. These prejudices manifest themselves in individuals and nations having policies which, overtly or covertly, subtly or blatantly, discriminate on the basis of religion, race, nationality, gender, age or sexual orientation--- religious and racial prejudices being among the most commonly encountered. Even a cursory examination of the history of religious bigotry amply demonstrates the frequent, prevalent and globally widespread nature of these practices. The consequences on individuals range from the relatively inconsequential, such as slurs and insults, to the devastating, including confiscation of property, expulsion from countries and mass slaughter. Religious and racial intolerance has also been responsible for a multitude of regional conflicts and global wars in the past as well as in the present, as evidenced by a mere perusal of current events. This article traces the repercussions of religious and racial intolerance through the eyes of historical and commemorative medals. As such, it attempts to be a Medallic History of Religious and Racial Intolerance. The discourse reviews briefly the history of this enormous field, concentrating on those countries and events where medals exist that exemplify the consequences of religious and racial prejudice. The coverage of the subject must, of necessity, be superficial, as the topic is so wide. Nevertheless, a group of medals has been selected that serve to illustrate, through imagery and wonderful art, that medals not only have provided a window through which to view historical events surrounding bigotry but also have been issued to actually promote religious and racial hatred.