Rediscovering Camden: the Preservation of a Revolutionary War Battlefield

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Griffith Rutherford in Revolutionary North Carolina James Matthew Am C Donald Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2006 Politics of the personal in the old north state: Griffith Rutherford in Revolutionary North Carolina James Matthew aM c Donald Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Mac Donald, James Matthew, "Politics of the personal in the old north state: Griffith Rutherford in Revolutionary North Carolina" (2006). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3625. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3625 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. POLITICS OF THE PERSONAL IN THE OLD NORTH STATE: GRIFFITH RUTHERFORD IN REVOLUTIONARY NORTH CAROLINA A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In The Department of History By James M. Mac Donald B.A., University of Delaware, 1995 M.A., Appalachian State University, 1997 May, 2006 To My Parents ii Acknowledgments I would like to thank my committee for their support and suggestions during the writing of my dissertation. As a student, I had the good fortune of taking seminars with each member beginning with my first graduate class at LSU. Mark Thompson became director late in the course of the project and generously agreed to chair the committee during the last semester. -

Vol. 2 No. 8 ___August

Vol. 2 No. 8 _____ ___________________________________ _ __ August 2005 THE BATTLE OF CAMDEN - new pastel by Pamela Patrick White – shows Patriot Gen. “Baron” Johannes DeKalb, leading his Maryland and Delaware Continentals in the hand-to-hand combat near the end of the early morning of August 16, 1780 at the Battle of Camden, near Gum Swamp. Baron de Kalb had been unhorsed and was fighting on foot, bleeding now from several wounds…Bullets, bayonets, and sabers had felled him. For an hour or more, this bare 600 fought off all attacks, charged with bayonet, re-formed, charged again, rallying about de Kalb’s vast figure as about a standard. Cornwallis called of much of the pursuit of the broken militia, and threw the bulk of his force on the stubborn Continentals. Then de Kalb was down, out of action at last with his eleventh wound of the day. Tarleton’s Legion charged again and the Delawares and the Marylanders were broken at last. Thus wrote William Allman at Hillsborough, North Carolina, on September 20, 1780. Allman, a soldier in Colonel Subblefields Regiment of Virginia Patriot Militia, was wounded at the Battle of Camden, taken prisoner, and managed to escape. Like many others from General Horatio Gates’ “grand army,” he rejoined his commander at Hillsborough after abandoning de Kalb and his men just north of Gum Swamp. In executing her newest work, “The Battle of Camden,” well-known historical artist Pamela Patrick White has captured the moment during the action when the British 33rd and 71st Regiments are charging with bayonets affixed de Kalb and the Continentals. -

Report of an Archeological Survey at Red Bank Battlefield Park (Fort Mercer), National Park, Gloucester County, New Jersey

"IT IS PAINFUL FOR ME TO LOSE SO MANY GOOD PEOPLE" REPORT OF AN ARCHEOLOGICAL SURVEY AT RED BANK BATTLEFIELD PARK (FORT MERCER), NATIONAL PARK, GLOUCESTER COUNTY, NEW JERSEY PREPARED FOR GLOUCESTER COUNTY DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION PREPARED BY AMERICAN BATTLEFIELD PROTECTION PROGRAM GRANT GA--- COMMONWEALTH HERITAGE GROUP, INC. WEST CHESTER, PENNSYLVANIA +VOF ARPA COMPLIANT COPY "IT IS PAINFUL FOR ME TO LOSE SO MANY GOOD PEOPLE" Report of an Archeological Survey at Red Bank Battlefield Park (Fort Mercer), National Park, Gloucester County, New Jersey Prepared for Gloucester County Department of Parks and Recreation Prepared by Wade P. Catts, RPA Robert Selig, Ph.D. Elisabeth LaVigne, RPA Kevin Bradley, RPA Kathryn Wood and David Orr, Ph.D. American Battlefield Protection Program Grant GA-2287-14-004 Commonwealth Heritage Group, Inc. 535 N. Church Street West Chester, PA 19380 FINAL June 2017 This material is based upon work assisted by a grant from the Department of the Interior, National Park Service. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of the Interior ABSTRACT This report presents the goals, methods, and results of an historical and archeological survey at Red Bank Battlefield Park, a park owned and administered by Gloucester County, New Jersey. The Park commemorates the American Revolutionary War battle fought October 22, 1777, between the American defenders of Fort Mercer (remnants of which are located in the Park) and a reinforced Hessian brigade. The project was funded by the American Battlefield Protection Program (ABPP) and followed the guidelines established by the ABPP as well as those of the state of New Jersey. -

Charge of the 63 Regiment of Foot up Hobkirk's Hill Gen. Nathanael

Vol. 5 No. 2.0___________________________________________________ __Second Edition 2008 Charge of the 63d Regiment of Foot up Hobkirk’s Hill Gen. Nathanael Greene Orders off the Cannon Artist Pamela Patrick White depicts the moment that Capt. John Smith and his Irish Light Infantry provides cover for the cannon’s crew to draw Greene’s 6-pounder off of the Hobkirk’s Hill battlefield. The original painting is on public display in the lobby at Carolina First Bank at 315 East DeKalb Street in Camden, SC. “As above mentioned the artillery had just come up as the battle began. The guns were merely unhooked from the limbers or fore-wheels and let down to fire on the enemy. The horses were not unharnessed, nor had the boys that drove them dismounted, but only removed a short distance from the cannon and now seeing a general retreat of the American Army attempted to get through the woods without going out into and along the road. They soon got them entangled among the trees and could not get along, but cut their horses and fled leaving the limbers of both pieces of cannon in the woods where they were found by the British and taken. Under the circumstances Genl Greene galloped up to Capt John Smith and ordered him to fall into the rear and save the cannon. Smith instantly came and found the artillerymen hauling off the pieces with the drag-ropes; he and his men laid hold and off they went in a trot, but had not gone far until he discovered that the British cavalry were in pursuit. -

Southern Campaign of the Revolution National Heritage Area Suitability / Feasibility Study North Carolina and South Carolina

SOUTHERN CAMPAIGN OF THE REVOLUTION National Heritage Area Suitability / Feasibility Study North Carolina and South Carolina National Park Service | U.S. Department of the Interior July 2014 EX ECUTIVE SUMMARY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION Following consideration of the counties above, the National Park Service determined The Department of the Interior, National that a focused corridor containing the Park Service (NPS), has prepared this concentration of historic resources that are National Heritage Area Suitability / Feasibility representative of the story best meets Study to determine the suitability and national heritage area feasibility criteria. feasibility of designating areas of North Carolina and South Carolina as a national heritage area. This study meets the THE NATIONAL SIGNIFICANCE OF THE requirements of the NPS interim National SOUTHERN CAMPAIGN OF THE Heritage Area Feasibility Study Guidelines AMERICAN REVOLUTION (2003) and the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969, as amended. Just as the American Revolution shaped the course of American history, the Southern Campaign dramatically altered the course of LEGISLATIVE HISTORY the Revolution. The initial phase of the war in the South brought a string of American Congress directed the Secretary of the victories, drove British forces from the Interior to conduct a study regarding the region, cowed American Loyalists, and suitability and feasibility of designating the pacified the southern states. Southern Campaign of the Revolution National Heritage Area (Public Law 109- The second phase of the Southern Campaign 338). The study was conducted in opened after nearly five years of bloody consultation with state historic preservation combat in other parts of America that had officers; state historical societies; the North resulted in a frustrating stalemate. -

South Carolina Brochure Final Jan15.Indd

South Carolina Battlefield Preservation 2015 Potential Funding Sources www.civilwar.org Table of Contents Introduction 3 Saving South Carolina’s Battlefields 5 State Government Funding Programs 7 Private Funding Programs 12 South Carolina National Heritage Areas 16 Civil War Trust Contacts 17 2 THE CIVIL WAR TRUST Preserving Our Battlefield Heritage Every year, hundreds of acres of our nation’s most important battlefields associated with the Civil War, the American Revolution and the War of 1812 are threatened by uncontrolled development. Preservationists struggle to save these hallowed grounds so that future generations can experience and appreciate the places where the nation’s freedoms were won, expanded, and preserved. The Civil War Trust (the “Trust”) is America’s largest nonprofit organization devoted to the preservation of our nation’s endangered Civil War battlefields. The Trust also promotes educational programs and heritage tourism initiatives to inform the public of the war’s history and the fundamental conflicts that sparked it. To further support our state and local partners, the Trust, through a grant from the National Park Service’s American Battlefield Protection Program (ABPP), have identified a multiplicity of national and state-level funding sources for the preservation of battlefields across the country recognized by the Civil War Sites Advisory Commission and the Report to Congress on the Historic Preservation of Revolutionary War and War of 1812 Sites in the United States. This information is being made available through both our website and within individual booklets for each of the 30 states with associated battlefields from these three wars. Each booklet offers an in-depth analysis of funding opportunities to save valuable battlefield properties. -

Vol. 2 No. 2 ______February 2005

Vol. 2 No. 2 _____ ___________________________________ __ February 2005 Editor’s Notes The plans for our Thomas Sumter Symposium (April SC and Ramseur’s Mill, NC (June 2005), Brattonsville, SC 8-9-10, 2005) and battlefield tours have really jelled. We have (July 2005), Camden, SC (August 2005) and Kings Mountain, a great line up of presenters to cover Gen. Sumter’s SC (October 2005) are already planning major 225th Southern multifaceted life. Dr. Dan Morrill, a dynamic speaker, will Campaign anniversary events. kick off with Sumter’s early service in the French and Indian We received the wonderful news of the satisfaction of War and the American Revolution. I am excited to announce the purchase money mortgage on the Battle of Camden site in that Dr. Jeff Dennis of Morehead State University will travel December with State of South Carolina funds. While there is with us and talk about his recent research on Thomas Sumter’s much more work to be done in property acquisition, planning, travels with Lt. Henry Timberlake’s Expedition to take three research, and interpretation at Camden, the public’s permanent Cherokee Chiefs to meet the great white father, King George access to this important battleground is now guaranteed. We III, in London. Dr. Tom Powers from USC Sumter will talk understand that various non-profit and governmental agencies about our great Gamecock as a militia and State Troop are now working on obtaining several other important Palmetto Commandant. Thomas Sumter Tisdale, descendent and State Revolutionary War sites. We hope we can announce author of the popular book on Thomas Sumter’s aristocratic, several milestone acquisitions here soon. -

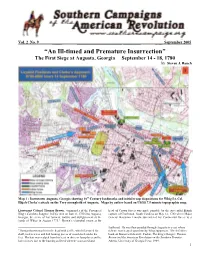

An Ill-Timed and Premature Insurrection, the First Siege At

Vol. 2 No. 9 _____ _______________________ _________ _ __ September 2005 “An Ill-timed and Premature Insurrection” The First Siege at Augusta, Georgia September 14 - 18, 1780 by Steven J. Rauch Map 1 - Downtown Augusta, Georgia showing 18th Century landmarks and initial troop dispositions for Whig Lt. Col. Elijah Clarke’s attack on the Tory stronghold of Augusta. Maps by author based on USGS 7.5 minute topographic map. Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Brown, commander of the Provincial head of Crown forces was made possible by the successful British King’s Carolina Rangers, led his men on June 8, 1780 into Augusta, capture of Charleston, South Carolina on May 12, 1780 where Major Georgia, the scene of his torment, torture and disfigurement at the General Benjamin Lincoln surrendered his Continental forces to a hands of Whigs in August 1775.1 Brown’s triumphal return at the feathered. He was then paraded through Augusta in a cart where 1Thomas Brown was hit in the head with a rifle, which fractured his ridicule was heaped upon him by Whig supporters. The definitive skull, tied to a tree and had burning pieces of wood stuck under his book on Brown is Edward J. Cashin, The King’s Ranger: Thomas feet. His hair was scalped from his head in three or four places and he Brown and the American Revolution on the Southern Frontier. lost two toes due to the burning suffered when he was tarred and Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1989. 1 powerful British land and naval force commanded by Lieutenant Savannah River and it served as the gateway to trade and General Henry Clinton. -

BATTLEFIELD UPDATE Newsletter of the American Battlefield Protection Program Fall 2001, No

BATTLEFIELD UPDATE Newsletter of the American Battlefield Protection Program Fall 2001, No. 77 REVOLUTIONARY WAR & WAR OF 1812 RECENT NATIONAL REGISTER LISTINGS HISTORIC PRESERVATION STUDY UPDATE In the past year, local and state preservation organizations Field surveyors are coming to a Revolutionary War or War have successfully added eight historic battlefield resources of 1812 site near you! The Congressionally mandated his- to the National Register of Historic Places. The National toric preservation study of the Revolutionary War and War Register is the nation’s official list of cultural resources of 1812 has moved into its field survey phase. More than worthy of preservation. National Register criteria are 70 surveyors are scouring the country to pinpoint and doc- designed to help state and local governments, Federal ument 786 sites associated with the two wars. The sites agencies, and others identify important historic and arche- include well known places such as Independence Hall and ological properties and raise awareness about the sites. For Fort McHenry, and lesser known places such as Crab more information about nominating a battlefield to the Island, New York, and Tookaubatchee, Alabama. The sites National Register, please contact Tanya Gossett at the are located in 31 states, the District of Columbia, and the ABPP at (202) 343-3449 or go to www.cr.nps.gov/nr/. U.S. Virgin Islands. Battle of Lyman’s Wagon Train, Hemphill County, A committee of historians and cultural resource specialists Texas, Listed August 13, 2001, and the Battle of selected the sites now being surveyed. The committee ranked Sweetwater Creek, Wheeler County, Texas, Listed August the relative historic importance of 2,800 events and places 13, 2001. -

Military Terrain Analysis 12-2017.Pdf

“THE ARMY MARCH’D AT DAY BREAK IN TWO COLUMNS” MILITARY TERRAIN ANALYSIS AND PLANNING RECOMMENDATIONS FOR TWO BRANDYWINE BATTLEFIELD STRATEGIC LANDSCAPES CHESTER COUNTY, PENNSYLVANIA AMERICAN BATTLEFIELD PROTECTION PROGRAM GRANT # GA2287-15-005 Prepared for The Chester County Planning Commission 601 Westtown Road, Suite 270 West Chester, PA 19380 by Wade P. Catts, RPA, Robert A. Selig, Ph.D., and Kevin Bradley, RPA Commonwealth Heritage Group, Inc. 535 North Church Street West Chester, Pennsylvania 1777 Map Depictions by Chester County Archives Department Recommendations by Chester County Planning Commission FINAL December 2017 This material is based upon work assisted by a grant from the Department of the Interior, National Park Service. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of the Interior. For distribution copies: Kristen L. McMasters, Archeologist and Grants Manager, National Park Service, American Battlefield Protection Program. 1849 C Street NW – Room 7228, Washington, DC 20210 (202) 354-2037 ABSTRACT This report provides detailed military t errain analyses for two Brandywine Battlefield Strategic Landscapes representing the Royal Army’s movements on September 9 and 10, their Encampment on September 10/11 and the movement of the Two Columns on the morning of September 11. The study builds upon earlier Chester County studies and current work, particularly work focused on the settlement pattern and the road network. Extensive historical and topographical research contributes to the analyses and interpretations. Notable among the documentary sources is the use of previously unavailable Hessian letters and journals. -

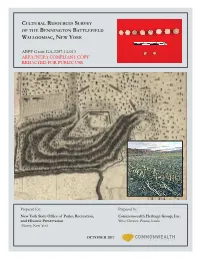

ABPP Grant GA-2287-14-013 ARPA/NHPA COMPLIANT COPY REDACTED for PUBLIC USE

CULTURAL RESOURCES SURVEY OF THE BENNINGTON BATTLEFIELD WALLOOMSAC, NEW YORK ABPP Grant GA-2287-14-013 ARPA/NHPA COMPLIANT COPY REDACTED FOR PUBLIC USE Prepared for: Prepared by: New York State Office of Parks, Recreation, Commonwealth Heritage Group, Inc. and Historic Preservation West Chester, Pennsylvania Albany, New York OCTOBER 2017 ARPA/NHPA COMPLIANT COPY REDACTED FOR PUBLIC USE CULTURAL RESOURCES SURVEY OF THE BENNINGTON BATTLEFIELD, WALLOOMSAC, NEW YORK Prepared for: New York State Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation 625 Broadway, 2nd Floor Albany, New York 12207 ABPP Grant GA-2287-14-013 Prepared by: Commonwealth Heritage Group, Inc. 2530 Spring Arbor Road Jackson, Michigan 49203 Robert Selig, Ph.D. Christopher T. Espenshade, RPA Wade P. Catts, RPA Elizabeth LaVigne, RPA James Montney October 2017 This material is based upon work assisted by a grant from the Department of the Interior, National Park Service. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of the Interior. For distribution copies: Kristen L. McMasters, Archeologist and Grants Manager, National Park Service, American Battlefield Protection Program 1849 C Street NW – Room 7228, Washington, DC 20210 (202) 354-2037 ABSTRACT ABSTRACT The metal detector survey recovered battle-related artifacts from many areas of state property and private lands. Of the 397 metal detector finds, at least 221 are battle-related, including dropped and impacted lead balls, buckshot, coins, and period buttons. The GPR prospection discovered two anomalies consistent with the potato pits that received battle dead, and another two anomalies that may represent expedient, single graves. -

Chapter 6. Cultural Element

Chapter 6. Cultural Element The Cultural Resources Element generates awareness and consideration of historical, archaeological, and heritage issues, as well as the unique attributes and defining character of the County and its communities. Cultural resources include historic buildings and structures, unique residential and commercial areas, archeological sites, entertainment venues and events, educational and religious institutions, and related features that impact the cultural assets of the County and its municipalities. The Element provides an overview of the historical development of Kershaw County, identifies significant historic and cultural resources, profiles local arts and cultural organizations, lists annual events and opportunities, and explores the current and potential economic impact of these resources on the community. Kershaw County has a rich cultural and historical resource base. County residents also have a strong awareness of and commitment to local history and historic places, as well as a deep appreciation for the arts. Preservation and enhancement of the County’s abundant historic and cultural resources directly benefit the community through increased tourism activity and revenue, revitalization of core commercial and residential districts, higher property values, stronger community identity, and enhanced attractiveness to new employers and residents. A. HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT Native American inhabitants of the area included the Catawba and Wateree. Although the first outside explorers to venture into the region were Spanish, early European economic activity in the area began in the early‐eighteenth century with the arrival of English traders from the coast to the western fringes of the colony. As part of the Fredericksburg Township, this network of early frontier settlements was designed to protect the colony’s coastal residents from Indian attacks.