OCEANIA NEWSLETTER No. 102, June 2021 Published Quarterly By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Forest, Resources and People in Bulungan Elements for a History of Settlement, Trade, and Social Dynamics in Borneo, 1880-2000

CIFOR Forest, Resources and People in Bulungan Elements for a History of Settlement, Trade, and Social Dynamics in Borneo, 1880-2000 Bernard Sellato Forest, Resources and People in Bulungan Elements for a History of Settlement, Trade and Social Dynamics in Borneo, 1880-2000 Bernard Sellato Cover Photo: Hornbill carving in gate to Kenyah village, East Kalimantan by Christophe Kuhn © 2001 by Center for International Forestry Research All rights reserved. Published in 2001 Printed by SMK Grafika Desa Putera, Indonesia ISBN 979-8764-76-5 Published by Center for International Forestry Research Mailing address: P.O. Box 6596 JKPWB, Jakarta 10065, Indonesia Office address: Jl. CIFOR, Situ Gede, Sindang Barang, Bogor Barat 16680, Indonesia Tel.: +62 (251) 622622; Fax: +62 (251) 622100 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: http://www.cifor.cgiar.org Contents Acknowledgements vi Foreword vii 1. Introduction 1 2. Environment and Population 5 2.1 One Forested Domain 5 2.2 Two River Basins 7 2.3 Population 9 Long Pujungan District 9 Malinau District 12 Comments 13 3. Tribes and States in Northern East Borneo 15 3.1 The Coastal Polities 16 Bulungan 17 Tidung Sesayap 19 Sembawang24 3.2 The Stratified Groups 27 The Merap 28 The Kenyah 30 3.3 The Punan Groups 32 Minor Punan Groups 32 The Punan of the Tubu and Malinau 33 3.4 One Regional History 37 CONTENTS 4. Territory, Resources and Land Use43 4.1 Forest and Resources 44 Among Coastal Polities 44 Among Stratified Tribal Groups 46 Among Non-Stratified Tribal Groups 49 Among Punan Groups 50 4.2 Agricultural Patterns 52 Rice Agriculture 53 Cash Crops 59 Recent Trends 62 5. -

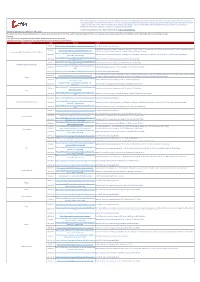

Diversity Visa Program, DV 2019-2021: Number of Entries During Each Online Registration Period by Region and Country of Chargeability

Diversity Visa Program, DV 2019-2021: Number of Entries During Each Online Registration Period by Region and Country of Chargeability The totals below DO NOT represent the number of diversity visas issued nor the number of selected entrants Countries marked with a "0" indicate that there were no entrants from that country or area. Countries marked with "N/A" were typically not eligible for that program year. FY 2019 FY 2020 FY 2021 Region Foreign State of Chargeabiliy Entrants Derivatives Total Entrants Derivatives Total Entrants Derivatives Total Africa Algeria 227,019 123,716 350,735 252,684 140,422 393,106 221,212 129,004 350,216 Africa Angola 17,707 25,543 43,250 14,866 20,037 34,903 14,676 18,086 32,762 Africa Benin 128,911 27,579 156,490 150,386 26,627 177,013 92,847 13,149 105,996 Africa Botswana 518 462 980 552 406 958 237 177 414 Africa Burkina Faso 37,065 7,374 44,439 30,102 5,877 35,979 6,318 2,591 8,909 Africa Burundi 20,680 16,295 36,975 22,049 19,168 41,217 12,287 11,023 23,310 Africa Cabo Verde 1,377 1,272 2,649 894 778 1,672 420 312 732 Africa Cameroon 310,373 147,979 458,352 310,802 165,676 476,478 150,970 93,151 244,121 Africa Central African Republic 1,359 893 2,252 1,242 636 1,878 906 424 1,330 Africa Chad 5,003 1,978 6,981 8,940 3,159 12,099 7,177 2,220 9,397 Africa Comoros 296 224 520 293 128 421 264 111 375 Africa Congo-Brazzaville 21,793 15,175 36,968 25,592 19,430 45,022 21,958 16,659 38,617 Africa Congo-Kinshasa 617,573 385,505 1,003,078 924,918 415,166 1,340,084 593,917 153,856 747,773 Africa Cote d'Ivoire 160,790 -

GENDER, RITUAL and SOCIAL FORMATION in WEST PAPUA in Memory of Ingrid, My Courageous Companion in Papua

GENDER, RITUAL AND SOCIAL FORMATION IN WEST PAPUA In memory of Ingrid, my courageous companion in Papua Cover: The dignitary Galus Mauria enacts the final stage of the Kaware ritual: while throwing lime-powder to mark the accasion he stabs an evil spirit with his ceremonial lance (apoko) in the sand of Paripia beach, West Mimika. From Pickell 2002: front cover. Photograph by Kal Muller. VERHANDELINGEN VAN HET KONINKLIJK INSTITUUT VOOR TAAL-, LAND- EN VOLKENKUNDE 258 jan pouwer GENDER, RITUAL AND SOCIAL FORMATION IN WEST PAPUA A configurational analysis comparing Kamoro and Asmat KITLV Press Leiden 2010 Published by: KITLV Press Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies) P.O. Box 9515 2300 RA Leiden The Netherlands website: www.kitlv.nl e-mail: [email protected] KITLV is an institute of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW) Cover: Creja ontwerpen, Leiderdorp ISBN 978 90 6718 325 3 © 2010 Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the copyright owner. Printed in the Netherlands Contents Acknowledgements ix Notes on spelling xi Abbreviations xiii Part One Gender and the ritual cycle in Mimika I Prologue 3 The structure of this book 7 Duality and reciprocity: two core concepts of Kamoro culture 11 General rituals -

Gender, Ritual and Social Formation in West Papua

Gender, ritual Pouwer Jan and social formation Gender, ritual in West Papua and social formation A configurational analysis comparing Kamoro and Asmat Gender,in West Papua ritual and social Gender, ritual and social formation in West Papua in West ritual and social formation Gender, This study, based on a lifelong involvement with New Guinea, compares the formation in West Papua culture of the Kamoro (18,000 people) with that of their eastern neighbours, the Asmat (40,000), both living on the south coast of West Papua, Indonesia. The comparison, showing substantial differences as well as striking similarities, contributes to a deeper understanding of both cultures. Part I looks at Kamoro society and culture through the window of its ritual cycle, framed by gender. Part II widens the view, offering in a comparative fashion a more detailed analysis of the socio-political and cosmo-mythological setting of the Kamoro and the Asmat rituals. These are closely linked with their social formations: matrilineally oriented for the Kamoro, patrilineally for the Asmat. Next is a systematic comparison of the rituals. Kamoro culture revolves around cosmological connections, ritual and play, whereas the Asmat central focus is on warfare and headhunting. Because of this difference in cultural orientation, similar, even identical, ritual acts and myths differ in meaning. The comparison includes a cross-cultural, structural analysis of relevant myths. This publication is of interest to scholars and students in Oceanic studies and those drawn to the comparative study of cultures. Jan Pouwer (1924) started his career as a government anthropologist in West New Guinea in the 1950s and 1960s, with periods of intensive fieldwork, in particular among the Kamoro. -

Coral and Concrete: Remembering Kwajalein Atoll Between Japan, America, and the Marshall Islands

Coral and Concrete: Remembering Kwajalein Atoll between Japan, America, and the Marshall Islands Reviewed by MARY L. SPENCER Coral and Concrete: Remembering Kwajalein Atoll; Between Japan, America, and the Marshall Islands, by Greg Dvorak. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2018. ISBN: 9780824855215, 314 pages (hardcover). Since my first experience in the early 1980’s with the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI), I’ve been stunned by the irony of the ignorance of the average American – including myself - regarding RMI relative to the actual significance of this complex portion of the Micronesian Region to US interests. Now, closing in on almost 75 years since the end of a world war that brought the US and Japan into savage combat in this constellation of hundreds of small islets and islands, RMI continues to quietly move forward, coping in its own culturally determined ways with the hideous impacts of the atomic and environmental assaults generated by the far larger, noisier powers. Today, RMI reaches its own decisions about how to cope with the challenges coming its way. Greg Dvorak, who grew up as an American kid living in the seclusion of the heavily fortified American missile range on Kwajalein Atoll in the RMI in the early 1970’s, opens his childhood memories, as well as his current academic analysis, of this special and secret Pacific Island preserve of the US military. Coral and Concrete is worth the attention of students and scholars of Micronesia and other Pacific Islands, and for the majority of the US reading public who have not heard of Kwajalein nor even the Marshall Islands. -

978-987-722-091-9

Inequality, Democracy and DevelopmentDemocracy Developmentunder Neoliberalism and Beyond South-South Tricontinental Collaborative Programme under Neoliberalism and Beyond South-South Tricontinental Collaborative Programme Inequality, Democracy and Development under Neoliberalism and Beyond Seventh South-South Institute Bangkok, 2014 The views and opinion expressed in this book are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Executive Secretariat of IDEAs First edition Inequality, Democracy and Development under Neoliberalism and Beyond (IDEAs, New Delhi, June 2015) ISBN: 978-987-722-091-9 International Development Economics Associates (IDEAs) Economic Research Foundation, 104 Munirka Enclave, Nelson Mandela Marg, New Delhi 110067 Tel: +91-11-26168791 / 26168793, Fax: +91-11- 26168792, www.networkideas.org Executive Secretary: Professor Jayati Ghosh Member of the Executive Committee: Professor C.P. Chandrasekhar CLACSO Consejo Latinoamericano de Ciencias Sociales - Conselho Latino-americano de Ciências Sociais (Latin American Council of Social Sciences) Estados Unidos 1168 | C1101AAX Ciudad de Buenos Aires, Argentina Tel. [54 11] 4304 9145, Fax: [54 11] 4305 0875, [email protected], www.clacso.org Deputy Executive Secretary: Pablo Gentili Academic Director: Fernanda Saforcada CODESRIA (Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa) Avenue Cheikh Anta Diop X Canal IV, BP 3304, CP 18524, Dakar, Senegal, Tel: (221) 33 825 98 22 ou (221) 33 825 98 23, Fax: (221) 33 824 12 89, http://www.codesria.org Executive Secretary: Dr. Ebrima Sall Head of the Research Programme: Dr. Carlos Cardoso Sponsored by the Swedish International Development Agency (SIDA) Contents List of Contributors 9. Commodification and Westernization: Explaining declining nutrition intake in Introduction contemporary rural China Zhun Xu & Wei Zhang 1. -

Shipping Operations Updated 6 April 2021

Please note, although we endeavour to provide you with the most up to date information derived from various third parties and sources, we cannot be held accountable for any inaccuracies or changes to this information. Inclusion of company information in this matrix does not imply any business relationship between the supplier and WFP / Logistics Cluster, and is used solely as a determinant of services, and capacities. Logistics Cluster /WFP maintain complete impartiality and are not in a position to endorse, comment on any company's suitability as a reputable service provider. If you have any updates to share, please email them to: [email protected] Shipping Operations Updated 6 April 2021 This bulletin is compiled to give all stakeholders an overview of the current impact of COVID-19 on Pacific shipping activities. It draws on sources from government, commercial and humanitarian sectors. The bulletin will now be circulated monthly. Overview • UN Bodies call for seafarers and aviation workers to be given priority access to vaccines • Massive congestion in European and Asian ports anticipated due to resolved Suez Canal blockage State / Territory Date Source Details 26-Mar-21 https://info.swireshipping.com/shipping-schedules/oceania See link for Swire Shipping schedule. Kaimana Hila arrives on 4 March. Maunawili arrives on 11 March. Daniel K. Inouye arrives on 18 March. Manukai arrives 25 March. Maunawili departs 25-Feb-21 https://www.matson.com/fss/reports/guam_s.pdf Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands on 9 March. Daniel K. Inouye departs on 14 March. Manukai departs 21 March. https://www.pdl123.co.nz/common/downloads/images/sch 24-Feb-21 Neptune Pacific has vessels arriving on 7 & 21 March, 10 & 21 April, 5 & 24 May, 4 & 18 June, 7 & 18 July, 20 & 31 August and 14 September. -

INFANT MORTALITY in NUAULU and NON-NUAULU COMMUNITIES in MALUKU TENGAH: Social Exclusion and Ethnicity in Indonesia1

INFANT MORTALITY IN NUAULU AND NON-NUAULU COMMUNITIES IN MALUKU TENGAH: Social Exclusion And Ethnicity In Indonesia1 By: Lusia Peilouw* Abstrak Nuaulu adalah salah satu komunitas adat di Maluku. Secara geografis komunitas ini tidak terisolasi seperti yang diasumsikan secara umum bahwa masyarakat adat biasanya hidup terisolasi di daerah terpencil. Mereka tinggal hanya beberapa kilometer dari ibukota kabupaten Maluku Tengah, di antara desa-desa yangjauh lebih berkembang. Sebuah penelitian demografis menggunakan kematian bayi dirancang untuk menerangkan fenomena sosial pada komunitas Nuaulu dan bukan Nuaulu. Ditemukan bahwa kematian bayi pada Nuaulu di Rouhua lebih tinggi dari pada bukan Nuaulu di Makariki. Faktor-faktor sosial yaitu pendidikan dan kesehatan dan ekonomi keluarga merupakan faktor determinan yang saling mempengaruhi satu dengan lainnya, sebagaimana dianalisa dengan menggunakan Mosley and Chen framework (1984). Secara laitis studi ini menemukan bahwa praktek-praktek budaya yang masih dipelihara oleh komunitas Nuaulu tidak akan menjadi masalah apabila kebutuhan sosiallain dan kebutuhan ekonomi terfasilitasi. Political will dan kepedulian pemerintahlah yang menjadi masalah dalam konteks ini. Mengabaikan komunitas adat dalam kebijakan pembangunan sosial menyebabkan masyarakat dalam komunitas ini rentan. Komunitas Nuaulu eli Rouhua hanyalah satu dari sekian banyak komunitas adat di negeri ini, dan terletak di daerah yang mudah dijangkau namun selama ini mereka hidup dalam keprihatinan dan kerentanan yang luar biasa. Bagaimana lebih buruknya kondisi komunitas-komunitas adat yang memang secara geografis tidak mudah dijangkau. Nuaulu is a tribal community in Maluku. Geographically this community is not isolated as is commonly assumed tribal communities living in remote areas are. Located among non-tribal communities, it is only a few kilometres from the centre of the Maluku Tengah District. -

2020, Pp. 261-266 GUEST EDITORIAL INTRODUCTION

Small States & Territories, 3(2), 2020, pp. 261-266 GUEST EDITORIAL INTRODUCTION Gender, politics and development in the small states of the Pacific Kerryn Baker Department of Pacific Affairs Australian National University Canberra, Australia [email protected] Roannie Ng Shiu Department of Pacific Affairs Australian National University Canberra, Australia [email protected] and Jack Corbett School of Social Sciences University of Southampton U. K. [email protected] Abstract: Gender has been a key focus of donor activism, domestic politics and academic commentary in the Pacific region over recent decades. The prevailing narrative highlights deficits, including the persistent absence of women from formal political representation, and the adverse consequences for economic and social development. This special section draws together papers that explore the nexus between gender, politics and development in the small states of the Pacific. Taken together, all the papers highlight the enduring need for a gendered lens in the study of politics and development in the region and beyond, while also complicating the deficit narrative by illustrating how gender relations are changing rapidly. In doing so the contributions reveal gaps and disjuncture in existing theoretical debates. Keywords: deficit narrative, development, equality, gender, Pacific politics, small states, social change © 2020 – Islands and Small States Institute, University of Malta, Malta. Introduction This special section of Small States & Territories 3(2), 2020, explores the nexus of gender, politics and development in the small states of the Pacific. The worlds of politics and development have always been gendered spaces, defined by male leadership and masculinised norms of behaviour. -

Book of Abstracts Edition 2016 09 10

Panels & Abstracts 16-18 SEPTEMBER 2016 SCHOOL OF ORIENTAL AND AFRICAN STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON ASEASUK Conference 2016 Disclaimer: Panel and abstract details are current as of 9 September 2016. While every effort has been made to ensure the completeness of this information and to verify details provided, ASEASUK, SOAS, and the organisers of this conference accept no responsibility for incorrect or incomplete information. Additional updated versions of this book of abstracts will be made until mid-August 2016 at which time a final hard copy will be printed for distribution at the conference. Organizing Committee Professor Michael W. Charney (SOAS), Committee Chair Professor Ashley Thompson (SOAS) Professor Matthew Cohen (Royal Holloway) Professor Carol Tan (SOAS) Dr. Ben Murtagh (SOAS) Dr. Angela Chiu (SOAS) Ms. Jane Savory (SOAS) SOAS Conference Office Support Mr. Thomas Abbs Ms. Yasmin Jayesimi Acknowledgments The Organizing Committee would like to thank the following people for special assistance in planning this conference: Dr. Tilman Frasch (Manchester Metropolitan University), Dr. Laura Noszlopy (Royal Holloway), Dr. Carmencita Palermo (University of Naples “L'Orientale”), Dr. Nick Gray (SOAS), Dr. Atsuko Naono (Wellcome Unit for the History of Medicine, University of Oxford), Dr. Li Yi (SOAS), Dr. Thomas Richard Bruce, and the many others who lent assistance in various ways. © 2016 ASEASUK and the SOAS, the University of London 1 Contents PANEL 1 The Political Economy of Inclusion: Current Reform Challenges in Indonesia 3 -

Minister Kabua's PRC4ECD Remarks

REMARKS: Minister Kitlang Kabua RMI Ministry of Education, Sports & Training PACIFIC REGIONAL COUNCIL FOR EARLY CHILDHOOD DEVELOPMENT (PRC4ECD) MEETING (VIRTUAL) 27 November 2020, 9:00 a.m. – 12 noon (Fiji time) 1. Hon. Johathan Curr (New Zealand High Commissioner), Hon. Ministers, Mr. Sheldon Yett (UNICEF Pacific Representative & ECD Pacific Secretariat), Dr. Micheal Samson (Director of Research Economic Policy, Research Institute), distinguished guests, ladies and gentlemen. Let me begin by extending warm greetings of Iakwe from President David Kabua and the people of the Republic of the Marshall Islands. 2. I also take this opportunity to thank the organizing committee for allowing RMI to speak at this Pacific Regional Council for Early Childhood Development (PR4ECD) meeting, to share recent achievements and challenges on ECD in the RMI- Kommol tata! 3. While the Marshall Islands is making steady progress to rolling out our Early Childhood Development plan, we recognize that much more needs to be done. The Multi-Sectoral Approach to ECD has both highs and lows. The positive side is that we all need to work together and consider the holistic needs of children and their families. The challenge is that the coordination necessary for success is slow moving. Inonoki bwe en Didbōlbōl, our nation's ECD slogan, loosely defined in English as ‘nurturing our children to flourish’. 4. Translating this slogan into action, we have demonstrated our commitment by setting our initial goals around policy reforms, bottom up approach to the 1 development of our curriculum framework, legislative reviews, harmonization of resources and strategies, costing analysis, classroom and health facilities upgrade and renovation, and the design work for a Conditional Cash Transfer (CCT) pilot program for vulnerable families with young children. -

Indigenous Peoples & Tourism

PART OF A SERIES OF INTRODUCTORY SUMMARIES ON TOPICS OF INTEREST TO OUR MEMBERS TourismConcern research briefing Indigenous Peoples & Tourism Research briefing 2017 • Helen Jennings Introduction Indigenous peoples? There are roughly 370 million Groups of people who originally populated certain parts of the world, now Indigenous people in the world often marginalised by nation states, are called by many names, for example today, belonging to 5,000 Aboriginals, First Nations and Native. In recent years the term Indigenous different groups. These groups peoples has gained currency to describe these groups, and alongside it have their own languages, has grown the term Indigenous tourism – often subsumed within ‘cultural cultures and traditions, all operating in very different tourism’. The ‘off the beaten path’ trails once reserved for specialists have political circumstances. They now become well-worn paths for millions of tourists searching for ‘authentic’ define themselves as ethnically experiences. This can be positive: it can assist cultural revitalisation and be a and culturally distinct from force for empowerment. On the other hand, it may see the often marginalised other inhabitants of the people and their villages becoming mere showcases for tourists, their culture countries/regions in which they reduced to souvenirs for sale, their environment to be photographed and left live. Typically, their cultures and traditions have had to without real engagement. withstand the social, cultural and This report aims to introduce some of the key issues surrounding Indigenous economic effects of colonialism, industrialisation and more peoples and tourism. It is split into sections dealing with main themes, offering recently, globalisation. Indigenous examples of both good and bad practice.