2.6 Oceania 145 2.6 OCEANIA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mediating the Imaginary and the Space of Encounter in the Papuan Gulf Dario Di Rosa

7 Mediating the imaginary and the space of encounter in the Papuan Gulf Dario Di Rosa Writing about the 1935 Hides–O’Malley expedition in the Highlands of Papua New Guinea, the anthropologist Edward Schieffelin noted that Europeans ‘had a well-prepared category – “natives” – in which to place those people they met for the first time, a category of social subordination that served to dissipate their depth of otherness’.1 However, this category was often nuanced by Indigenous representations of neighbouring communities, producing significant effects in shaping Europeans’ understanding of their encounters. Analysing the narrative produced by Joseph Beete Jukes,2 naturalist on Francis Price Blackwood’s voyage of 1842–1846 on HMS Fly, I demonstrate the crucial role played by Torres Strait Islanders as mediators from afar of European encounters with Papuans along the coast of the Gulf of 1 Schieffelin and Crittenden 1991: 5. 2 Jukes 1847. As Beer (1996) shows, the viewing position of on-board scientists during geographical explorations was a particular one, led by their interests (see, from a different perspective, Fabian (2000) on the relevance of ‘natural history’ as episteme of accounts of explorations). This is a reminder of the high degree of social stratification within the ‘European’ micro-social community of the ship’s crew, a social hierarchy that shaped the texts available to the historians. Although he does not treat the problem of social stratification as such, see Thomas 1994 for a well-argued discussion about the different projects that guided various colonial actors. See also Dening 1992 for vivid case of power relations in the micro-social cosmos of a ship. -

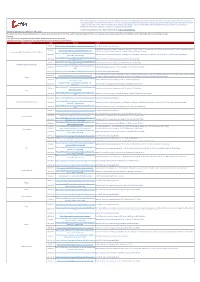

Diversity Visa Program, DV 2019-2021: Number of Entries During Each Online Registration Period by Region and Country of Chargeability

Diversity Visa Program, DV 2019-2021: Number of Entries During Each Online Registration Period by Region and Country of Chargeability The totals below DO NOT represent the number of diversity visas issued nor the number of selected entrants Countries marked with a "0" indicate that there were no entrants from that country or area. Countries marked with "N/A" were typically not eligible for that program year. FY 2019 FY 2020 FY 2021 Region Foreign State of Chargeabiliy Entrants Derivatives Total Entrants Derivatives Total Entrants Derivatives Total Africa Algeria 227,019 123,716 350,735 252,684 140,422 393,106 221,212 129,004 350,216 Africa Angola 17,707 25,543 43,250 14,866 20,037 34,903 14,676 18,086 32,762 Africa Benin 128,911 27,579 156,490 150,386 26,627 177,013 92,847 13,149 105,996 Africa Botswana 518 462 980 552 406 958 237 177 414 Africa Burkina Faso 37,065 7,374 44,439 30,102 5,877 35,979 6,318 2,591 8,909 Africa Burundi 20,680 16,295 36,975 22,049 19,168 41,217 12,287 11,023 23,310 Africa Cabo Verde 1,377 1,272 2,649 894 778 1,672 420 312 732 Africa Cameroon 310,373 147,979 458,352 310,802 165,676 476,478 150,970 93,151 244,121 Africa Central African Republic 1,359 893 2,252 1,242 636 1,878 906 424 1,330 Africa Chad 5,003 1,978 6,981 8,940 3,159 12,099 7,177 2,220 9,397 Africa Comoros 296 224 520 293 128 421 264 111 375 Africa Congo-Brazzaville 21,793 15,175 36,968 25,592 19,430 45,022 21,958 16,659 38,617 Africa Congo-Kinshasa 617,573 385,505 1,003,078 924,918 415,166 1,340,084 593,917 153,856 747,773 Africa Cote d'Ivoire 160,790 -

Torresstrait Islander Peoples' Connectiontosea Country

it Islander P es Stra eoples’ C Torr onnec tion to Sea Country Formation and history of Intersection of the Torres Strait the Torres Strait Islands and the Great Barrier Reef The Torres Strait lies north of the tip of Cape York, Torres Strait Islanders have a wealth of knowledge of the marine landscape, and the animals which inhabit it. forming the northern most part of Queensland. Different marine life, such as turtles and dugong, were hunted throughout the Torres Strait in the shallow waters. Eighteen islands, together with two remote mainland They harvest fish from fish traps built on the fringing reefs, and inhabitants of these islands also embark on long towns, Bamaga and Seisia, make up the main Torres sea voyages to the eastern Cape York Peninsula. Although the Torres Strait is located outside the boundary of the Strait Islander communities, and Torres Strait Islanders Great Barrier Reef Marine Park, it is here north-east of Murray Island, where the Great Barrier Reef begins. also live throughout mainland Australia. Food from the sea is still a valuable part of the economy, culture and diet of Torres Strait Islander people who have The Torres Strait Islands were formed when the land among the highest consumption of seafood in the world. Today, technology has changed, but the cultural use of bridge between Australia and Papua New Guinea the Great Barrier Reef by Torres Strait Islanders remains. Oral and visual traditional histories link the past and the was flooded by rising seas about 8000 years ago. present and help maintain a living culture. -

Navigating Boundaries: the Asian Diaspora in Torres Strait

CHAPTER TWO Tidal Flows An overview of Torres Strait Islander-Asian contact Anna Shnukal and Guy Ramsay Torres Strait Islanders The Torres Strait Islanders, Australia’s second Indigenous minority, come from the islands of the sea passage between Queensland and New Guinea. Estimated to number at most 4,000 people before contact, but reduced by half by disease and depredation by the late-1870s, they now number more than 40,000. Traditional stories recount their arrival in waves of chain migration from various islands and coastal villages of southern New Guinea, possibly as a consequence of environmental change.1 The Islanders were not traditionally unified, but recognised five major ethno-linguistic groups or ‘nations’, each specialising in the activities best suited to its environment: the Miriam Le of the fertile, volcanic islands of the east; the Kulkalgal of the sandy coral cays of the centre; the Saibailgal of the low mud-flat islands close to the New Guinea coast; the Maluilgal of the grassy, hilly islands of the centre west; and the Kaurareg of the low west, who for centuries had intermarried with Cape York Aboriginal people. They spoke dialects of two traditional but unrelated languages: in the east, Papuan Meriam Mir; in the west and centre, Australian Kala Lagaw Ya (formerly called Mabuiag); and they used a sophisticated sign language to communicate with other language speakers. Outliers of a broad Melanesian culture area, they lived in small-scale, acephalous, clan-based communities and traded, waged war and intermarried with their neighbours and the peoples of the adjacent northern and southern mainlands. -

Torres Strait Regional Economic Investment Strategy, 2015-2018 Phase 1: Regional Business Development Strategy

Page 1 Torres Strait Regional Economic Investment Strategy, 2015-2018 Phase 1: Regional Business Development Strategy A Framework for Facilitating Commercially-viable Business Opportunities in the Torres Strait September 2015 Page 2 This report has been prepared on behalf of the Torres Strait Regional Authority (TSRA). It has been prepared by: SC Lennon & Associates Pty Ltd ACN 109 471 936 ABN 74 716 136 132 PO Box 45 The Gap Queensland 4061 p: (07) 3312 2375 m: 0410 550 272 e: [email protected] w: www.sashalennon.com.au and Workplace Edge Pty Ltd PO Box 437 Clayfield Queensland 4011 p (07) 3831 7767 m 0408 456 632 e: [email protected] w: www.workplaceedge.com.au Disclaimer This report was prepared by SC Lennon & Associates Pty Ltd and Workplace Edge Pty Ltd on behalf of the Torres Strait Regional Authority (TSRA). It has been prepared on the understanding that users exercise their own skill and care with respect to its use and interpretation. Any representation, statement, opinion or advice expressed or implied in this publication is made in good faith. SC Lennon & Associates Pty Ltd, Workplace Edge Pty Ltd and the authors of this report are not liable to any person or entity taking or not taking action in respect of any representation, statement, opinion or advice referred to above. Photo image sources: © SC Lennon & Associates Pty Ltd Page 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY A New Approach to Enterprise Assistance in the Torres Strait i A Plan of Action i Recognising the Torres Strait Region’s Unique Challenges ii -

Menzies School of Health Research

MENZIES SCHOOL OF HEALTH RESEARCH 2020-21 Pre-Budget Submission September 2020 Contact: Professor Alan Cass Director, Menzies School of Health Research Ph: 08 8946 8600 Email: [email protected] Web: www.menzies.edu.au ABN: 70 413 542 847 Menzies School of Health Research (Menzies) is pleased to put forward its 2020-21 Pre-Budget submission. 1. Summary of recommendations The medical and health research sector has an important role in supporting economic growth, job creation and attracting investment to Australia. This role has been further emphasised in key policy statements from both the Northern Territory and Commonwealth Governments to ensure the future prosperity of northern Australia. For example, medical and health research is a stated economic priority in the Northern Territory Economic Development Framework and its Economic Reconstruction Priorities, as well as being highlighted as a strategic priority in the Commonwealth’s White Paper on Developing Northern Australia. Directly related to supporting medical and health research in northern Australia, this pre-budget submission requests that the Commonwealth provide $5m to support a four (4) year extension to the Northern Australia Tropical Disease Collaborative Research Program (NATDCRP), administered by Menzies School of Health Research in collaboration with seven (7) of Australia’s leading health research organisations – James Cook University, Telethon Kids Institute, Burnet Institute, The University of Sydney, the South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute, Doherty Institute and QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute. The NATDCRP – now referred to as the HOT North Program - was announced as a $6.8m budget measure by the Minister for Trade and Investment, the Hon Andrew Robb on 10 May 2015. -

Torres Strait Islanders: a New Deal

The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia TORRES STRAIT ISLANDERS: A NEW DEAL A REPORT ON GREATER AUTONOMY FOR TORRES STRAIT ISLANDERS House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Affairs August 1997 Canberra Commonwealth of Australia 1997 ISBN This document was produced from camera-ready copy prepared by the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs and printed by AGPS Canberra. The cover was produced in the AGPS design studios. The graphic on the cover was developed from a photograph taken on Yorke/Masig Island during the Committee's visit in October 1996. CONTENTS FOREWORD ix TERMS OF REFERENCE xii MEMBERSHIP OF THE COMMITTEE xiii GLOSSARY xiv SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS xv CHAPTER 1 – INTRODUCTION REFERRAL TO COMMITTEE.......................................................................................................................................1 CONDUCT OF THE INQUIRY ......................................................................................................................................1 SCOPE OF THE REPORT.............................................................................................................................................2 PRELIMINARY OBSERVATIONS .................................................................................................................................3 Commonwealth-State Cooperation ....................................................................................................................3 -

Shipping Operations Updated 6 April 2021

Please note, although we endeavour to provide you with the most up to date information derived from various third parties and sources, we cannot be held accountable for any inaccuracies or changes to this information. Inclusion of company information in this matrix does not imply any business relationship between the supplier and WFP / Logistics Cluster, and is used solely as a determinant of services, and capacities. Logistics Cluster /WFP maintain complete impartiality and are not in a position to endorse, comment on any company's suitability as a reputable service provider. If you have any updates to share, please email them to: [email protected] Shipping Operations Updated 6 April 2021 This bulletin is compiled to give all stakeholders an overview of the current impact of COVID-19 on Pacific shipping activities. It draws on sources from government, commercial and humanitarian sectors. The bulletin will now be circulated monthly. Overview • UN Bodies call for seafarers and aviation workers to be given priority access to vaccines • Massive congestion in European and Asian ports anticipated due to resolved Suez Canal blockage State / Territory Date Source Details 26-Mar-21 https://info.swireshipping.com/shipping-schedules/oceania See link for Swire Shipping schedule. Kaimana Hila arrives on 4 March. Maunawili arrives on 11 March. Daniel K. Inouye arrives on 18 March. Manukai arrives 25 March. Maunawili departs 25-Feb-21 https://www.matson.com/fss/reports/guam_s.pdf Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands on 9 March. Daniel K. Inouye departs on 14 March. Manukai departs 21 March. https://www.pdl123.co.nz/common/downloads/images/sch 24-Feb-21 Neptune Pacific has vessels arriving on 7 & 21 March, 10 & 21 April, 5 & 24 May, 4 & 18 June, 7 & 18 July, 20 & 31 August and 14 September. -

SC2.10 Masig (Yorke) Island Maps

Schedule 2: Mapping SC2.10 Masig (Yorke) Island maps Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 675 This page is intentionally left blank. Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 676 Zenadth Kes Planning Scheme: Planning Scheme for The Torres Strait Island Regional Council Area Saibai Island Ugar LEGEND Island KUKI EXISTING FACILITIES AND INFRASTRUCTURE Airstrip IBIS Store Barge Ramp Sacred Site Cemetery School Child Care Facility Sewerage Infrastructure Erub Church Island Sports Field Community Hall TSIRC Buildings Defence Patrol Depot Telecommunications Electricity Infrastructure Infrastructure Waste Facility ¸Å Fire Station MARUS Water Supply Infrastructure UMI Health Centre EBRINZAR BOUNDARIES AND FEATURES SAU Direction to the nearest Islands BANIUGUB WAK Road Coming of the Light AUPSIRIAM (monument) KOBIN LGA MUR Kuki (NW Winds - January to April) Japanese Burrial Ground Sager (SE Winds - May to December) PATTERN OF LAND USE IDID Lawrences Rd DOPE Township Environmental Management and Conservation Masig 2 Rd Steven Jeff Rd NATURAL ENVIRONMENT KUBUR Lowattas Rd Turtle Barge Ramp Rd Williams Rd FUTURE FACILITIES, INFRASTRUCTURE AND ACTIVITIES MUKUNKUP Dans Rd Aous Rd Township Expansion JDL "Road Town Centre Core " Possible Location for Park and Community Charlies Rd Garden Airstrip Rd Masig" 1 Rd DURI Masig 5 Rd Data Sources: GUDAMADU Unless stated below all landuse, road, or natural feature data shown is from the Strategic Landuse Plan (SLUP) by the RPS Group 2010. Community Consultation 2013: Local Names, Places and identified facilities DARDAR Queensland Dept. Natural Resources and Environment: Imagery, KOD LGA Boundaries, Terrain data and Flooding layers KEKUR AECOM: all strategic framework, zoning and local area plan data is Masig 6 Rd modified from the SLUP and DNRM source data. -

Melbourne Biomedical Precinct Studley Rd to an Exceptional Network Economic and Investment Growth Swinburne University of of Skilled Workers, Quality for the State

The Royal Children’s Hospital + The Murdoch Children’s Research Institute The Royal Women’s Hospital Darwin Walter & Eliza Hall Institute Monash Institute of Pharmaceutical NT Science, Monash University + CSIRO QLD Royal Melbourne Hospital WA Brisbane C Florey Institute SA e m ete ry Rd The University of Melbourne NSW Perth Sydney A Precinct approach Victorian Comprehensive Cancer Centre Adelaide Royal Pde Canberra + Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre The Doherty Institute to collaboration Flemington Rd Elgin St St Vincent’s Hospital Melbourne Hobart Melbourne, Grattan St Swanston St Australia and innovation Arden St Curzon St Elizabeth St Lygon St La Trobe University Queensberry St d R g r e b Burgundy St Rathdowne St l Chetwynd St Victoria St e > id e Melbourne Brain Centre H r Peel St e Austin Health p Plan Melbourne, Victoria’s key metropolitan Franklin St p Melbourne has biomedical La Trobe St U Austin Hospital planning strategy, highlights the precincts Banksia St capabilities unparalleled in around Melbourne, Monash, Deakin, Olivia Newton-John Australia and amongst the and La Trobe universities as clusters CSL Cancer Wellness & world’s best. We are home which offer significant opportunities (Poplar Road) Research Centre for innovation as well as employment, Melbourne Biomedical Precinct Studley Rd to an exceptional network economic and investment growth Swinburne University of of skilled workers, quality for the state. Technology education providers, leading The Melbourne Biomedical Precinct Deakin University St Kilda Rd research institutes and a Partners are largely collocated to the Princes Hwy Commercial Rd Burwood & Geelong Campuses sophisticated health system. north of Melbourne’s CBD close to Monash University, Australia’s highest ranking university, Clayton � Caulfield There is a growing body of evidence the University of Melbourne. -

2010-2011 Annual Report

Annual Report 2010-2011 Mastery of disease through discovery | www.wehi.edu.au Contents 1 About the institute 3 Director’s and Chairman’s report 5 Discovery 8 Cancer and Haematology 10 Stem Cells and Cancer 12 Molecular Genetics of Cancer 14 Chemical Biology 16 Molecular Medicine 18 Structural Biology 20 Bioinformatics 22 Infection and Immunity 24 Immunology The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute 26 Autoimmunity and Transplantation of Medical Research 28 Cell Signalling and Cell Death 1G Royal Parade 30 Inflammation Parkville Victoria 3052 Australia Telephone: (+61 3) 9345 2555 32 Molecular Immunology Facsimile: (+61 3) 9347 0852 34 Publications WEHI Biotechnology Centre 36 Awards 4 Research Avenue 37 Translation La Trobe R&D Park Bundoora Victoria 3086 Australia Translating our research 38 Telephone: (+61 3) 9345 2200 40 Developing our research Facsimile: (+61 3) 9345 2211 42 Patents www.wehi.edu.au www.facebook.com/WEHIresearch 43 Education www.twitter.com/WEHI_research 46 2010-11 graduates ABN 12 004 251 423 47 Seminars Acknowledgements 48 Institute awards Produced by the institute’s Community Relations department 49 Engagement Managing editor: Penny Fannin Editor: Liz Williams 51 Strategic partners Writers: Liz Williams, Vanessa Solomon and Julie Tester 52 Scientific and medical community Design and production: Simon Taplin Photography: Czesia Markiewicz and Cameron Wells 54 Public engagement 57 Engagement with schools Cover image 58 Donor and bequestor engagement Art in Science finalist 2010 Vessel webs 59 Sustainability Dr Leigh Coultas, Cancer and Haematology division 60 The Board This image shows the delicate intricacy in the developing eye of a transient population of web-like blood vessels. -

Fellowship of the Australian Academy of Health and Medical Sciences January 2019

FELLOWSHIP OF THE AUSTRALIAN ACADEMY OF HEALTH AND MEDICAL SCIENCES JANUARY 2019 Fellowship Year Name of Fellow Primary Position Primary Institution State Office Inducted Pro Vice Chancellor of Health and Medicine Professor John (Robert) Aitken Fellow 2015 The University of Newcastle NSW Laureate Professor of Biological Sciences Senior Staff Specialist The Children’s Hospital at Westmead Professor Ian Alexander Fellow 2015 NSW Head, Gene Therapy Research Unit Children’s Medical Research Institute Professor Warren Alexander Fellow 2015 Joint Head, Cancer and Haematology Division The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research VIC Professor Katie (Katrina) Allen Fellow 2015 Theme Director, Population Health Consultant Paediatrician Murdoch Children's Research Institute, The Royal Children’s Hospital VIC Professor Craig Anderson Fellow 2015 Senior Director, Neurological and Mental Health Division The George Institute for Global Health NSW Professor Vicki Anderson Fellow 2015 Head of Psychology, RCH Mental Health Royal Children’s Hospital VIC Professor Warwick Anderson Fellow 2015 Deputy Director, Centre for Values, Ethics and the Law in Medicine The University of Sydney NSW Professor Warwick Anderson AM Honorary Fellow 2015 Secretary General International Human Frontier Science Program Organization International Professor Ian Anderson AO Fellow 2018 Deputy Secretary, Department of Prime Minister & Cabinet Commonwealth Government of Australia ACT Professor James Angus AO Honorary Fellow 2015 Honorary Professorial Fellow and Emeritus