Canadian Rail No188 1967

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scottish Association for Public Transport

President: Tom Hart 11 Queens Crescent Chairman: Dr. John McCormick Glasgow G4 9BL Secretary: Arthur Homan-Elsy Tel: 07760 381 729 Membership email: [email protected] Secretary: Scott Simpson Treasurer: John Ferris web: www.sapt.org.uk Scottish Association for Public Transport To: The Newsdesk 20/9/13 PRESS RELEASE: for Immediate Release The New Railway Race to the North* ScotRail Refranchising Opportunity The ScotRail refranchising Invitation to Tender is due to be issued this winter by Transport Scotland. The Scottish Association for Public Transport welcomes the investment in rail that is planned for Central Belt rail electrification between Edinburgh, Glasgow and Stirling, the new Edinburgh-Glasgow High Speed Line, and the prospect of a fleet of new electric trains. But we are concerned that progress on improving InterCity links from Inverness, Aberdeen, Dundee, and Perth is lagging far behind. Planned road spending on the A9 and A96 will make rail much less competitive with the car, unless there is a major improvement in train speed and comfort in the near future. Our Association is today calling for a major upgrade of train services linking Inverness , Aberdeen, Dundee, Perth and the Central Belt. This should be specified by Transport Scotland in the ScotRail franchise Invitation to Tender. Details of our analysis are appended. These have also been sent to Transport Scotland, HITRANS, NESTRANS and TACTRAN. Dr. John McCormick, SAPT Chairman, said today: “The new ScotRail franchise to start in 2015 is expected to last for up to 10 years. This is a once-in-a-decade opportunity for a step-change in train travel in the Highlands, the North-east, and Tayside. -

Part 3 of the Bibliography Catalogue

Bibliography - L&NWR Society Periodicals Part 3 - Railway Magazine Registered Charity - L&NWRSociety No. 1110210 Copyright LNWR Society 2012 Title Year Volume Page Railway Magazine Photos. Junction at Craven Arms Photos. Tyne-Mersey Power. Lime Street, Diggle 138 Why and Wherefore. Soho Road station 465 Recent Work by British Express Locomotives Inc. Photo. 2-4-0 No.419 Zillah 1897 01/07 20 Some Racing Runs and Trial Trips. 1. The Race to Edinburgh 1888 - The Last Day 1897 01/07 39 What Our Railways are Doing. Presentation to F.Harrison from Guards 1897 01/07 90 What Our Railways are Doing. Trains over 50 mph 1897 01/07 90 Pertinent Paragraphs. Jubilee of 'Cornwall' 1897 01/07 94 Engine Drivers and their Duties by C.J.Bowen Cooke. Describes Rugby with photos at the 1897 01/08 113 Photo.shed. 'Queen Empress' on corridor dining train 1897 01/08 133 Some Railway Myths. Inc The Bloomers, with photo and Precedent 1897 01/08 160 Petroleum Fuel for Locomotives. Inc 0-4-0WT photo. 1897 01/08 170 What The Railways are Doing. Services to Greenore. 1897 01/08 183 Pertinent Paragraphs. 'Jubilee' class 1897 01/08 187 Pertinent Paragraphs. List of 100 mile runs without a stop 1897 01/08 190 Interview Sir F.Harrison. Gen.Manager .Inc photos F.Harrison, Lord Stalbridge,F.Ree, 1897 01/09 193 TheR.Turnbull Euston Audit Office. J.Partington Chief of Audit Dept.LNW. Inc photos. 1897 01/09 245 24 Hours at a Railway Junction. Willesden (V.L.Whitchurch) 1897 01/09 263 What The Railways are Doing. -

138904 03 Dirtmile.Pdf

breeders’ cup dirt mile BREEDERs’ Cup DIRT MILE (GR. I) 7th Running Santa Anita Park $1,000,000 Guaranteed FOR THREE-YEAR-OLDS AND UPWARD ONE MILE Northern Hemisphere Three-Year-Olds, 123 lbs.; Older, 126 lbs. Southern Hemisphere Three-Year-Olds, 120 lbs.; Older, 126 lbs. All Fillies and Mares allowed 3 lbs. Guaranteed $1 million purse including travel awards, of which 55% of all monies to the owner of the winner, 18% to second, 10% to third, 6% to fourth and 3% to fifth; plus travel awards to starters not based in California. The maximum number of starters for the Breeders’ Cup Dirt Mile will be limited to twelve (12). If more than twelve (12) horses pre-enter, selection will be determined by a combination of Breeders’ Cup Challenge Winners, Graded Stakes Dirt points and the Breeders’ Cup Racing Secretaries and Directors panel. Please refer to the 2013 Breeders’ Cup World Championships Horsemen’s Information Guide (available upon request) for more information. Nominated Horses Breeders’ Cup Racing Office Pre-Entry Fee: 1% of purse Santa Anita Park Entry Fee: 1% of purse 285 W. Huntington Dr. Arcadia, CA 91007 Phone: (859) 514-9422 To Be Run Friday, November 1, 2013 Fax: (859) 514-9432 Pre-Entries Close Monday, October 21, 2013 E-mail: [email protected] Pre-entries for the Breeders' Cup Dirt Mile (G1) Horse Owner Trainer Alpha Godolphin Racing, LLC Lessee Kiaran P. McLaughlin B.c.4 Bernardini - Munnaya by Nijinsky II - Bred in Kentucky by Darley Broadway Empire Randy Howg, Bob Butz, Fouad El Kardy & Rick Running Rabbit Robertino Diodoro B.g.3 Empire Maker - Broadway Hoofer by Belong to Me - Bred in Kentucky by Mercedes Stables LLC Brujo de Olleros (BRZ) Team Valor International & Richard Santulli Richard C. -

Lotus Approach/BIB00.APR

London & North Western Railway Society L&NWR Library The Library is available for browsing and reference at the Society Study Centre in Kenilworth (see downloadable leaflet in the Study Centre section of the web site). It will not be possible to borrow any of the material. Subject to copyright restrictions copies may be made at the Study Centre. This list is organised groups for various subjects. The search tool (Binocular icon) in the Adobe Acrobat Reader can also be used to find particular words in the document descriptions. Other PDF readers have similar search facilities. If you find any errors in the list please inform the Librarian Copyright L&NWR Society 2017 Registered Charity - L&NWR Society No.1110210 GENERAL REFERENCE - NON-RAILWAY L&NWR Society Library List PUBLISHER/ TITLE AUTHOR ISBN YEAR GENERAL REFERENCE - NON-RAILWAY Copyright for Archivists and users of archives. 2nd Edition Padfield T Facet Publishing 2004 1-85604-512-9 Historical Day/Date finder. Covers the whole railway period. A3 sheet of calendars. BIBLIOGRAPHY & GENERAL REFERENCE Crewe & Wolverton Negative Register. Bound photocopies. Copies in Archives. LNWR LNWR Publicity Department Negative Register. Bound photocopies. Copies in LNWR Archives. A Bibliography of British Railway History 1st Ed 1965, 2nd Ed 1983 Ottley G Allen & Unwin 1983 0-11-290334-7 LNWR Bibliography Part 1 Books & Special Pubs Part 2 Magazines & Periodicals LNWR Society 1983 File of Book and record reviews The Ordnance Survey Atlas of Great Britain. 1982 Ordnance Survey 1982 Road Atlas of the British Isles 1988 The Railmag Index. Index to Trains Ill. 1946-61. -

Transportation and Transformation the Hudson's Bay Company, 1857-1885

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for Summer 1983 Transportation And Transformation The Hudson's Bay Company, 1857-1885 A. A. den Otter Memorial University of Newfoundland Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons den Otter, A. A., "Transportation And Transformation The Hudson's Bay Company, 1857-1885" (1983). Great Plains Quarterly. 1720. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/1720 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. TRANSPORTATION AND TRANSFORMATION THE HUDSON'S BAY COMPANY, 1857 .. 1885 A. A. DEN OTTER Lansportation was a prime consideration in efficiency of its transportation system enabled the business policies of the Hudson's Bay Com the company to defeat all challengers, includ pany from its inception. Although the company ing the Montreal traders, who were absorbed in legally enjoyed the position of monopoly by 1821. Starving the competition by slashing virtue of the Royal Charter of 1670, which prices, trading liquor, and deploying its best granted to the Hudson's Bay Company the servants to critical areas were other tactics the Canadian territory called Rupert's Land, this company employed to preserve its fur empire. 1 privilege had to be defended from commercial The principal means by which the Hudson's intruders. From the earliest days the company Bay Company defended its trade monopoly, developed its own transportation network in nevertheless, was to maintain an efficient trans order to maintain a competitive edge over its portation system into Rupert's Land. -

Winnipeg À La Carte

WINNIPEG bEr 2013 em À LA CARTEGh Nov May throu ➊ WINNIPEG CITY TOUR – Ô TOURS Welcome to Winnipeg, Manitoba’s Departing from Union Station, the tour takes visitors to The Forks, Winnipeg’s favourite gathering vibrant capital city located at the centre place; St. Boniface, Winnipeg’s French Quarter and home to a vibrant Francophone community and beautiful cathedral; the Exchange District, one of North America’s finest collections of turn-of-the- of Canada and North America. With a last-century architecture; Assiniboine Park, the city’s largest green space with beautiful flower and population of more than 762,000, the sculpture gardens; and the Manitoba Legislative Building, built in the Beaux-Arts style using fossil-rich city has a cosmopolitan, international flair Manitoba limestone and replete with mysterious Masonic references. and a warm, welcoming spirit. We invite Check in with the Ô TOURS representative at the arrivals area of Union Station. hours: 8:30 am to 11 am (transportation included); available during the Winnipeg stopover. VIA passengers to take advantage of their Cost: $30 per person stopover to stretch their legs and see Contact: 204-254-3170 or 1-877-254-3170 | otours.net some of the city’s top attractions. From the architecturally distinctive Exchange ➋ THE WINNIPEG RAILWAY MUSEUM District and the joie de vivre of its French Inside Winnipeg’s historic Union Station at The Forks, you’ll discover the city’s railway history and artifacts. See the Countess of Dufferin, the first steam locomotive on the Prairies, along with diesel Quarter to the heart of its past at The and electric locomotives. -

WINNIPEG À LA CARTE MAY THROUGH NOVEMBER 2015 Photo Credit: Canadian Museum for Human Rights

WINNIPEG À LA CARTE MAY THROUGH NOVEMBER 2015 Photo Credit: Canadian Museum for Human Rights Welcome to Winnipeg, Manitoba’s vibrant capital 1 WINNIPEG CITY TOUR — Ô TOURS city located in the heart of Canada and North Departing from the train station, the tour takes you to some of Winnipeg’s must-sees, including America. With a population of more than 782,000, the historic Forks district—one of Winnipeg’s loveliest public spaces; St. Boniface, Winnipeg’s the city has a cosmopolitan, international flair French Quarter, which is home to a vibrant Francophone community and beautiful cathedral; and a warm, welcoming spirit. We invite VIA Assiniboine Park, the city’s largest green space with beautiful flower and sculpture gardens; and the Manitoba Legislative Building, built in the Beaux-Arts style using fossil-rich Manitoba passengers to take advantage of their stopover to limestone replete with mysterious Masonic references. stretch their legs and discover some of the city’s Check in with the Ô TOURS representative at the arrivals area of the train station. top attractions—many of which are only minutes Hours: Tours offered Mondays, Thursdays and Saturdays. From 8:30 a.m. to 11:00 a.m. from Union Station. From the distinct architecture (transportation included), available during the Winnipeg stopover of the Exchange District, to the joie de vivre of Cost: $30 per person the French Quarter and The Forks—Manitoba’s Contact: 1 204 254-3170 or 1 877 254-3170 | otours.net busiest tourist attraction where the very ground is steeped in history—Winnipeg is a confluence of 2 THE WINNIPEG RAILWAY MUSEUM old and new, traditional and avant-garde. -

For Reciprocating Steam Locomotives Mean Piston Speed

P.1 of 4 Note 125. Historical Mean Piston Speed ( MPS ) for reciprocating steam locomotives Mean Piston Speed ( MPS ) has been much used in this review for the reason explained in Note 13 Part 1. It was thought that a historical look at this factor would be of interest to viewers. It was recognised quite early in the development of reciprocating steam locomotive engines that MPS was important in the stressing of the piston and connecting rod. With these parts always in ferrous material, and so of the same density, their stress is proportional to ( MPS )2. In standard steam engine design the piston, being double-acting, is supported by a cross-head outside the cylinder. Therefore it is not subjected to side loads and can be very short and just sufficient to carry sealing rings. In the 1907 GWR “ Star ” class ( for which a drawing is available, thanks to GWR and “ Childrens’ Encyclopedia ”! ) the axial length was only 11% of the stroke. For locomotive steam engines travelling at V MPH on driving wheels of D feet in diameter and with a piston stroke of S feet the relation is MPS = 56.02 x ( S/D ) x V ft/min. Examples ( 1 ). In 1838 Isambard Brunel ordered a pair of locomotives from an outside builder for the GWR and specified that MPS should not exceed 280 ft/min ( 1.4 m/s ) at 30 MPH ( Ref. 1 ). This for cast iron pistons at something under 140C and with wrought iron connecting rods. Actually, Brunel’s specification could only be met by having the cylinders carried on their own set of wheels, with the crank geared-up 2.3:1 to the driving pair, and with the boiler carried separately on another-truck ( see Fig. -

Heritage | History Itinerary

HERITAGE | HISTORY ITINERARY HALF DAY Your day starts with breakfast at the Tallest Poppy, located Continue your day at The Forks—a gathering place for inside the former Occidental Hotel, a Winnipeg landmark. more than 6,000 years where the Red and Assiniboine Built in 1886, the hotel has stood watch through much of the rivers meet. Explore the site and plaques scattered city’s history, changing hands numerous times and earning throughout that relate the history of this significant spot. itself a notorious reputation along the way. Now home to Visit the Oodena Celebration Circle, Balance of Spirit this hip spot popular with foodies, they serve up wholesome Within and the Peace Meeting Site for a reflection on the food make with local ingredients. city’s aboriginal roots. After breakfast, it’s time to head to the nearby Manitoba If you’re feeling peckish, head into The Forks Market Museum, where the province’s history comes to life. Stroll and sample a variety of ethnic options from baba-made the streets of Winnipeg as they were in the 1920s or hop perogies to stuffed rotis to crispy samosas. Browse the aboard the life-sized replica of the Nonsuch ketch. Make market’s eclectic shops and pick up unique, handmade gifts your way through the Hudson’s Bay gallery and discover our and treasures. fur trading roots and finish your visit with a stop at Churchill’s shore line 450 million years ago. FULL DAY In the afternoon, head to St. Boniface and Le Musee de Then, make your way to Fort Gibraltar, originally a North Saint-Boniface Museum. -

774G Forks Walkingtour.Indd

Walking Tours Walking Tours A word about using this guide... MINI-TOURS This publication is comprised of six mini-tours, arranged around the important historical and developmental stories of The Forks. Each of these tours includes: • a brief introduction • highlights of the era’s history • a map identifying interpretive plaques, images and locations throughout The Forks that give you detailed information on each of these stories The key stories are arranged so you can travel back in time. Start by familiarizing yourself with the present and then move back to the past. GET YOUR BEARINGS If you can see the green dome of the railway station and the green roof of the Hotel Fort Garry, you are looking west. If you are looking at the red canopy of the Scotiabank Stage, you are pointed north. If you see the wide Red River, you are looking east and by looking south you see the smaller Assiniboine River. 3 Take Your Place! If you are a first time visitor, take this opportunity to let your eyes and imagination wander! Welcome Imagine your place among the hundreds of immigrant railway Newcomer! workers toiling in one of the industrial buildings in the yards. You hear dozens of foreign languages, strange to your ear, as you You are standing on land that has, for thousands of years, repair the massive steam engines brought into the yards and been a place of great activity. It has seen the comings and hauled into the roundhouse. Or maybe you work in the stables, goings – of massive glacial sheets of ice – of expansive lakes caring for the hundreds of horses used in pulling the wagons that teeming with wildlife of every description – of new lands transport the boxcars full of goods to the warehouse district nearby. -

Canadian Rail • No.349 FEBRUARY 1981

• Canadian Rail • No.349 FEBRUARY 1981 ........~IAN Published J:lOntllly by The Canadian Railroad Historical Association P.O. Box 22, Station G Montreal,Quebec ,Canada H3B 3J5 '55N 0008 -4875 EDITOR : Fred F. Angus CALGARY & SOOTH WESTERN DIVISION CO-EDITOR: M. Peter Murphy 60-6100 4th Ave. NE BUSINESS CAR: Dave J. Scott Calgary, Alberta T2A 5Z8 OFFICIAL CARTOGRAPHER: William A. Germaniuk OTTAWA LAYOUT: Michel Paulet BYTOWN RAILWAY SOCIETY P.O. Box 141, Station A Otta\~a, Ontario Kl N 8Vl NEW BRUNSWICK DIVISION P.O. Box 1162 Saint John, Ne\~ Brun swi c k E2L 4G 7 CROWSNEST AND KEHLE-VALLEY DIVISION FRONT COVER: A BALLAST TRAIN DURING CONSTRUC P.O. Box 400 TION OF THE PACIFIC SECTION of Cranbrook, British Columbia the C.P.R . by Andrew Onderdonk. V1C 4H9 -The locomotive is No.4. "SAVONA" PACIFIC COAST DIVISION which had formerly been No. 5 "CARSON" of the Virginia and P.O. Box 1006, Station A. Vancouver Truckee. This 2-6-0 survived British Columbia V6C 2Pl until 1926 when, as C.N.R. 7083. ROCKY MOUNTAIN DIVISION it \~as scrapped. Coll ection of P.O. Box 6102, Station C, Edmonton Orner Lavall~e. Alberta T5B 2NO OPPOSITE: WINDSOR-ESSEX DIVISION C.P.R. LOCOMOTIVE t\O. 150 is 300 Cabana Road East, Windsor shown on the Pic River Bridge Ontario N9G lA2 during the construction days of the 1880's. This engine had been TORONTO & YORK DIVISION bui It by DUbs in Sco tl and in 1873 P;O. Box 5849, Terminal A, Toronto and. before being purchased by Ontario M5W lP3 C.P. -

Newsletter — David M

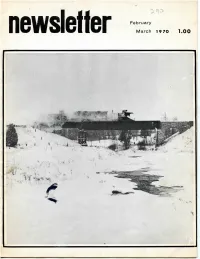

The Cover Wintertime, and with the season comes the use of railway ploughs to keep the lines clear of snow. In this scene, a plough train crosses the Rouge River northbound on CP Rail's Havelock Sub, just north of the boundary of Metropolitan Toronto (Steeles Avenue). newsletter — David M. More, Number 290 February-March, 1970 Coming Events Published monthly by the Upper Canada Railway Society Inc., Box 122, Terminal A, Toronto 116, Ontario. Rcffular meetinpis of the Society are held on the third Friday oi each month (except July and August) at 589 Mt. Pleasant Road, Robert D. McMann, Editor. Toronto. Ontario. 8.00 p.m. Contributions to the Newsletter are solicited. No responsibility can be assumed for loss or non-return of material, although every care will be exercised when return is requested. Apr. 17: Regular meeting. Ross Hoover "Railways of Manitoba" (Fri.) Illustrated by slides. To avoid delay, please address Newsletter items directly to the appropriate address; Apr. 24: Hamilton Chapter meeting, 8:00 p.m. In the CN Station (Frl.) Board Room, James St. N., Hamilton. Robert D. McMann 80 Bannockburn Avenue Apr. 25: UCRS steam excursion with CN 6218 Toronto to Lindsay. (Sat.) Leaves Toronto Union Station 0900 hours Eastern Standard Toronto 180, Ontario Time. Fares adults $12.00, children $6.00, infants SI.00 Return to Toronto about 1820 hours. ASSISTA.NT EDITOR: .1. A. (Alf) Nanders Apr. 26: Six hour TTC streetcar trip around Toronto. Departs EB (Traction Topics) 7475 Homeside Gardens (Sun.) King & Yonge at 0930 hours Eastern Daylight Time. Fare ."•lalton, Ontario $4.00.