Oblique Main Arguments As Localizing Predications in Hindi/Urdu Annie Montaut

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-Kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal David L

Western Washington University Western CEDAR A Collection of Open Access Books and Books and Monographs Monographs 2008 Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal David L. Curley Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/cedarbooks Part of the Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Curley, David L., "Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal" (2008). A Collection of Open Access Books and Monographs. 5. https://cedar.wwu.edu/cedarbooks/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Books and Monographs at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in A Collection of Open Access Books and Monographs by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Table of Contents Acknowledgements. 1. A Historian’s Introduction to Reading Mangal-Kabya. 2. Kings and Commerce on an Agrarian Frontier: Kalketu’s Story in Mukunda’s Candimangal. 3. Marriage, Honor, Agency, and Trials by Ordeal: Women’s Gender Roles in Candimangal. 4. ‘Tribute Exchange’ and the Liminality of Foreign Merchants in Mukunda’s Candimangal. 5. ‘Voluntary’ Relationships and Royal Gifts of Pan in Mughal Bengal. 6. Maharaja Krsnacandra, Hinduism and Kingship in the Contact Zone of Bengal. 7. Lost Meanings and New Stories: Candimangal after British Dominance. Index. Acknowledgements This collection of essays was made possible by the wonderful, multidisciplinary education in history and literature which I received at the University of Chicago. It is a pleasure to thank my living teachers, Herman Sinaiko, Ronald B. -

LCSH Section K

K., Rupert (Fictitious character) Motion of K stars in line of sight Ka-đai language USE Rupert (Fictitious character : Laporte) Radial velocity of K stars USE Kadai languages K-4 PRR 1361 (Steam locomotive) — Orbits Ka’do Herdé language USE 1361 K4 (Steam locomotive) UF Galactic orbits of K stars USE Herdé language K-9 (Fictitious character) (Not Subd Geog) K stars—Galactic orbits Ka’do Pévé language UF K-Nine (Fictitious character) BT Orbits USE Pévé language K9 (Fictitious character) — Radial velocity Ka Dwo (Asian people) K 37 (Military aircraft) USE K stars—Motion in line of sight USE Kadu (Asian people) USE Junkers K 37 (Military aircraft) — Spectra Ka-Ga-Nga script (May Subd Geog) K 98 k (Rifle) K Street (Sacramento, Calif.) UF Script, Ka-Ga-Nga USE Mauser K98k rifle This heading is not valid for use as a geographic BT Inscriptions, Malayan K.A.L. Flight 007 Incident, 1983 subdivision. Ka-houk (Wash.) USE Korean Air Lines Incident, 1983 BT Streets—California USE Ozette Lake (Wash.) K.A. Lind Honorary Award K-T boundary Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Moderna museets vänners skulpturpris USE Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary UF Ka Iwi Scenic Shoreline Park (Hawaii) K.A. Linds hederspris K-T Extinction Ka Iwi Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Moderna museets vänners skulpturpris USE Cretaceous-Paleogene Extinction BT National parks and reserves—Hawaii K-ABC (Intelligence test) K-T Mass Extinction Ka Iwi Scenic Shoreline Park (Hawaii) USE Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children USE Cretaceous-Paleogene Extinction USE Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) K-B Bridge (Palau) K-TEA (Achievement test) Ka Iwi Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Koro-Babeldaod Bridge (Palau) USE Kaufman Test of Educational Achievement USE Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) K-BIT (Intelligence test) K-theory Ka-ju-ken-bo USE Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test [QA612.33] USE Kajukenbo K. -

(IJTSRD) Volume 4 Issue 1, December 2019 Available Online: E-ISSN: 2456 – 6470

International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development (IJTSRD) Volume 4 Issue 1, December 2019 Available Online: www.ijtsrd.com e-ISSN: 2456 – 6470 A Descriptive Study of Standard Dialect and Western Dialect of Odia Language in Terms of Linguistic Items Debiprasad Pany Assistant Professor, Department of English, IGIT (Indira Gandhi Institute of Technology), Sarang, Odisha, India ABSTRACT How to cite this paper : Debiprasad Pany Language is a unique blessing to human beings. Human beings are bestowed "A Descriptive Study of Standard Dialect with the faculty of language from very primitive age. Language makes human and Western Dialect of Odia Language in beings social and in a society human beings communicate with the help of Terms of Linguistic Items" Published in language. Odia is one among the constitutionally approved language of India. International Journal Odisha is situated in the eastern part of India. Presently, this state has thirty of Trend in Scientific districts. Odisha is bound to the north by the state Jharkhand, to the northeast Research and by the state West Bengal, to the east by the Bay- of- Bengal, to the south by the Development (ijtsrd), state Andhra Pradesh, and to the west by the state Chhattisgarh. The ISSN: 2456-6470, languages used by the neighboring states have a lot of influence on Odia Volume-4 | Issue-1, language. In this present study a modest attempt has been made to high light December 2019, IJTSRD29632 the differences between Standard Odia and Western Odia dialects. Various pp.626-630, URL: linguistic items used by the western Odia dialect users have marked www.ijtsrd.com/papers/ijtsrd29632.pdf differences compared to the standard Odia. -

Plural Markers in World Languages and Their Arabic Cognates Or Origins

Zaidan Ali Jassem The Arabic Cognates or Origins of Plural Markers in World Languages: A Radical Linguistic Theory Approach THE ARABIC COGNATES OR ORIGINS OF PLURAL MARKERS IN WORLD LANGUAGES: A RADICAL LINGUISTIC THEORY APPROACH Zaidan Ali Jassem Department of English Language and Translation, Qassim University, P.O.Box 6611, Buraidah, KSA Email: [email protected] APA Citation: Jassem, Z. A. (2015). The Arabic cognates or origins of plural markers in world languages: a radical linguistic theory approach. Indonesian EFL Journal, 1(2), 144-163 Received: 02-12-2014 Accepted: 01-05-2015 Published: 01-07-2015 Abstract: This paper traces the Arabic origins of "plural markers" in world languages from a radical linguistic (or lexical root) theory perspective. The data comprises the main plural markers like cats/oxen in 60 world languages from 14 major and minor families- viz., Indo-European, Sino-Tibetan, Afro-Asiatic, Austronesian, Dravidian, Turkic, Mayan, Altaic (Japonic), Niger-Congo, Bantu, Uto-Aztec, Tai-Kadai, Uralic, and Basque, which constitute 60% of world languages and whose speakers make up 96% of world population. The results clearly show that plural markers, which are limited to a few markers in all languages comprised of –s/-as/-at, -en, -im, -a/-e/-i/-o/-u, and Ø, have true Arabic cognates with the same or similar forms and meanings, whose differences are due to natural and plausible causes and different routes of linguistic change. Therefore, the results reject the traditional classification of the Comparative Method and/or Family Tree Model of such languages into separate, unrelated families, supporting instead the adequacy of the radical linguistic theory according to which all world languages are related to one another, which eventually stemmed from a radical or root language which has been preserved almost intact in Arabic as the most conservative and productive language. -

Rivalry of Iranian Littérateurs Against Persian Poets of India: Its Effect on Evolution of Classical Literature of Urdu

South Asian Studies A Research Journal of South Asian Studies Vol. 29, No. 1, January – July 2014, pp. 149-159 Rivalry of Iranian Littérateurs against Persian Poets of India: Its effect on Evolution of Classical Literature of Urdu Shagufta Bano Government Degree College for Women, Salamatpura, Lahore. Zahida Habib University of Education, Lahore. Muhammad Sohail University of the Punjab, Lahore. Abstracts Tens of million people of Pakistan, India and Bangladesh speak Urdu language and hundreds of people of South Asia understand it. It is such an auspicious language that many pious Sufis and holy saints participated in its growth and development. When the Muslims came in India they spoke Persian, Arabic and Turkish languages. Although they did not enforce any of these languages by force in India, but Persian was the official language of the regions under Muslim rule. Therefore, the people had to get a nodding acquaintance of Persian. On the other hand many words related to Muslim mode of life and Islamic sociology entered into local language. Although the local language started growing rapidly but it did not get the status of mature literary language that Persian enjoyed. Therefore, the scholars, intellectuals and litterateurs of India preferred Persian language for expression of serious subjects. But the Iranian scholars and poets showed incredulity about Persian works of the Indians. These antagonistic feelings against the Indian littérateurs turned them towards their local language. This paper examines the effect of this reactionary attitude on the development of Urdu. Key Word: Iranian litterateurs, Indian Poets, rivalry, Persian literacy tradition, reaction. Introduction When the Muslims came to India there had been different languages spoken in different areas including Sanskrit and different prak’rits (dialects) like Maghdi, Urd Maghadi, Maharashtri, Paki and Shoorsaini as well as many minor languages. -

Nepali and an Analyzed Corpus, a Descriptive Grammar of (Acharya).Pdf

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Informaiion C om pany 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800 521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

“Form of Request and Advice in English, and Bajhangi”

CHAPTER-I INTRODUCTION This is the study entitled “Form of Request and Advice in English, and Bajhangi”.This introductory part consists of background of the study, statement of the problem, objectives of the study, research questions, significance of the study, delimitations of the study, and operational definition of the key terms. 1.1Background of the Study It is believed that more than six thousand different languages are spoken in the present world. Really, we cannot say the fact origin of the spoken language. It is guessed that some types of spoken language developed between 100,000 and 50,000 years ago. The written systems of them are developed about 5000 years ago (Yule, 2008, p.1, as cited in Bohara, 2010).Generally, language can be defined as a voluntary vocal system of human communication. Language is the properly of human beings. Actually, language had made human communication effective, efficient, easier and entertaining. However, communication is alsopossible through other modes such as visual, tactile, olfactory and gustatory. The main purpose of language is to communicate. Crystal (2003, p.255) defines “Language refers to the concerts act of speaking, writing or singing in a given situation.The notion ofparole or performance”. Widdowson(1983) defines the language from cultural perspective by saying “Language is a system of arbitrary vocal system which permits all people in given cultural or other people who have learned the system of that culture, to communicate or to interest”. Wardhaugh (2000, p.1) defines “A language is what the member of a particular society speak”. Similarly, Richards et al. -

Thumri, Ghazal, and Modernity in Hindustani Music Culture

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research John Jay College of Criminal Justice 2010 Thumri, Ghazal, and Modernity in Hindustani Music Culture Peter L. Manuel CUNY Graduate Center How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/jj_pubs/309 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 9 Thumri, Ghazal, and Modernity in HindustaniMusic Culture PETER MANUEL If historians of Indian classical music have been obliged to rely primarily upon a finite and often enigmatic set of treatises and iconographic sources, historical studies of semi-classical genres like thumri and ghazal confront even more formidable challenges. Such styles and their predecessors were largely ignored by Sanskrit theoreticians, who tended to be more interested in hoary modal and metrical systems than in contemporary vernacular or regional-language genres sung by courtesans. It is thus inevitable that attempts to reconstruct the development of such genres involve considerable amounts of conjecture, and in some senses raise more questions than they answer. Nevertheless, thumri, ghazal, and earlier counterparts, which we may retrospectively call "light-classical", have played too important a role in South Asian music to be ignored by historians. Further, as I shall suggest, the study of their evolution may yield pa1ticular insights into the nature of Hindustani music history, especially of the modem period. Central to this study is a fundamental paradox characterizing thumri and ghazal history: specifically, that while both genres may be seen as mere variants or particular efflorescences in a long series of similar counterparts dating back to the early common era, there are other senses in which they are unique products of a particular historical moment marked by unprecedented socio-historical features. -

Representing Pakistan Through Folk Music and Dance

University of Alberta Representing Pakistan through Folk Music and Dance by Shumaila Hemani A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Ethnomusicology Department of Music © Shumaila Hemani Fall 2011 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Mein tā koī khayāl I am just a thought Hun milī sā nāl khayāl dey Let my thought become a reality (Sachal Sarmast) Dedicated to the three most inspiring women in my life: my mother, Regula and Veengas Abstract: Folk music is a site of contestation to define national culture and language amongst the cultural elites in Pakistan. The elites who established cultural institutions for the promotion of folk music represented Pakistan either as a cultural unit with Islam and the Urdu language as its unifying bond, or resisted this position by considering Pakistan as a culturally diverse unit, in which national culture could emerge only through a synthesis of regional cultures and not through the imposition of a single culture and language. -

Nepali in Sikkim

CHAPTER II NEPALI IN SIKKIM R. NAKKEERAR 1. INTRODUCTION Nepali is one of the 22 Scheduled languages of India. In Indian Census prior to 1991, the language was identified as Gorkhali/ Nepali. From 1991 Census onwards it is appearing as Nepali. Nepali, being mainly distributed in West Bengal, has been studied under Linguistic Survey of India-West Bengal Volume. But, being the first populous language of Sikkim state, the same has been studied for Sikkim state also to assess the divergence and convergence in Nepali being spoken in two different linguistic environments. Whereas in West Bengal, Nepali is spoken amidst the superposed Bengali language, In Sikkim, it is spoken in the environment of Tibeto-Burman speech communities in West Bengal. Further, Nepali has been studied in Himachal Pradesh too where the language exists in mixed environment of both Indo-Aryan and Tibeto-Burman languages. The present volume of LSI-Sikkim (Part II) gives the detailed description of Nepali, spoken in Sikkim along with comparing the same with Nepali studied in West Bengal and Himachal Pradesh. The present study has been presented based on the study conducted at Gangtok during March April, 2010. The linguistic data has been elicited by Shri Valman Subba, Translator, Nepali Section and Shri Megraj Gurung, Under Secretary of Nepali Section in Sikkim Secretariat at Gangtok. The non-linguistic information has been collected from the Sikkim Secretariate (Nepali Section), Sikkim Legislative Hostel, Gangtok. 1.1. FAMILY AFFILIATION -I), Nepali is the language of Eastern Pahari Group of an Indo-Aryan family of languages. The languages of the Pahari group are spreaded along the Himalayan region from the west of Himachal Pradesh to Sikkim in the east and Nepali is the only representative of Eastern Pahari sub- group. -

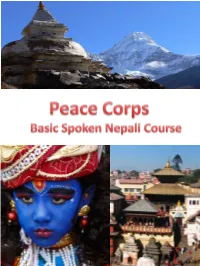

Peace Corps Volunteers of Nepal in Mind but Is Equally Useful for Any Foreigners Who Want to Learn Nepali

PREFACE This book is written with the needs of Peace Corps volunteers of Nepal in mind but is equally useful for any foreigners who want to learn Nepali. The material presented here is based on spoken Nepali. Effort has been made to make the material both linguistically and cul turally authentic as far as possible. However, the regional variances (Nepali spoken in Eastern vs. Western parts of Nepal) in spoken Nepali as well as in grammar have caused some difficulty in such an effort. In such cases, we have chosen the ones, which, in our experience and knowledge, have appeared to be most common. The differences between the native Nepali speakers (Brahmins, Kshatrys, etc.) and those who speak it as a second language (Gurungs, Newars, Magars, Rais etc.) cause another set of problems. The Nepali spoken by the first group may be considered as correct but the latter represents the majority of the speakers in the country. The material in this book will reflect the influence of this majority group. So while we accept that some of the grammatical patterns used here are not correct in the purest sense, we can claim that this is the way the majority of people do actually speak and consequently most important for the foreigners to learn. The book contains forty lessons. Each lesson is supplemen ted by grammar notes and explanations of the usage of different lan guage items that may cause confusion for the learners. Each lesson also includes a list of new words with its English equivalents and con jugation of verbs whenever necessary. -

Classical Language : Odia

Odisha Review Classical Status to Odia Language Classical Language : Odia Subrat Kumar Prusty Government of India has established four criteria Odisha has largest number of pre-historic for grant of classical status to the modern Indian sites. Lots of Paleolithic stone implements have language. The classical status to any language been found in various sites of Odisha. Similar sites brings fame to the language and provides greater of copper Bronze Age and Iron Age are available opportunities for research and development. in plenty. The latest archaeological excavation has taken place in 2013 at Harirajpur. The findings In this context, one can judiciously think of excavation includes human skeleton, broken about giving this classical status to Odia language. potteries, carbon, earthen pots, agricultural stone The ancientness of the Odia language is being implements, animal bones, flooring of houses, proved from its soil which speaks about two types remains of hearth, which claim to be 4000 years of language from very beginning. The old. The Tel river civilization throwslight on a great development of Odia can be seen through its civilization existing in Kalahandi, Balangir, spoken and written forms. The spoken languages Koraput regions in the past that is recently getting are expressed in two ways. One preserved explored. The discovered archaeological wealth through folk forms and the other preserved of Tel Valley speaks of a well civilized, urbanized, through cave paintings. The songs sung at the time cultured people inhabiting on this land around of birth, death and other functions are preserved, 2000 years ago. The Radhanagar Fort of Jajpur stories are painted through cave paintings both was the centre of circle on the periphery of which represent the creativity of the underlying literature.