Representing Pakistan Through Folk Music and Dance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alphabetical List of Successful Candidates for Recruitment to the Posts of Building Inspector (Bs-14) on Contract Basis For

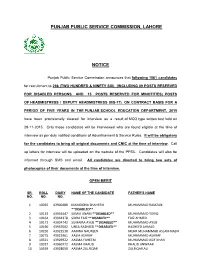

PUNJAB PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION, LAHORE NOTICE Punjab Public Service Commission announces that following 1561 candidates for recruitment to 296 (TWO HUNDRED & NINETY SIX) (INCLUDING 09 POSTS RESERVED FOR DISABLED PERSONS AND 15 POSTS RESERVED FOR MINOTITIES) POSTS OF HEADMISTRESS / DEPUTY HEADMISTRESS (BS-17) ON CONTRACT BASIS FOR A PERIOD OF FIVE YEARS IN THE PUNJAB SCHOOL EDUCATION DEPARTMENT, 2015 have been provisionally cleared for interview as a result of MCQ type written test held on 29-11-2015. Only those candidates will be interviewed who are found eligible at the time of interview as per duly notified conditions of Advertisement & Service Rules. It will be obligatory for the candidates to bring all original documents and CNIC at the time of interview. Call up letters for interview will be uploaded on the website of the PPSC. Candidates will also be informed through SMS and email. All candidates are directed to bring two sets of photocopies of their documents at the time of interview. OPEN MERIT SR. ROLL DIARY NAME OF THE CANDIDATE FATHER'S NAME NO. NO. NO. 1 10065 43900486 MAMOONA SHAHEEN MUHAMMAD RAMZAN **DISABLED** 2 10133 43934447 SAMIA ANAM **DISABLED** MUHAMMAD TARIQ 3 10164 43944378 SIDRA FAIZ **DISABLED** FAIZ AHMED 4 10172 43904742 SUMAIRA AYUB **DISABLED** MUHAMMAD AYUB 5 10190 43937002 UNSA RASHEED **DISABLED** RASHEED AHMAD 6 10250 43923510 AAMNA NAUREEN MEHR MUHAMMAD ASLAM NASIR 7 10275 43922961 AASIA ASHRAF MUHAMMAD ASHRAF 8 10321 43926922 AASMA FAHEEM MUHAMMAD ASIF KHAN 9 10327 43960772 AASMA KHALID KHALID ANWAAR -

FRIDAY 17Th NOVEMBER 2017 4:00 - 5:00 Pm Exhibition Inauguration and Opening Ceremony (Gallery) 5:30 - 6:00 Pm Guests to Be Seated (Hall 2)

FAIZ INTERNATIONAL FESTIVAL 17th – 19th November 2017 Alhamra Halls, Mall Road Lahore All events are free and open for all. (Except Tina Sani performance) FRIDAY 17th NOVEMBER 2017 4:00 - 5:00 pm Exhibition Inauguration and Opening Ceremony (Gallery) 5:30 - 6:00 pm Guests to be seated (Hall 2) لو پھر بسنت آئی pm 7:20 – 6:00 Play by Ajoka Theatre (Hall 2) SATURDAY 18th NOVEMBER 2017 Time Hall 1 Hall 2 Hall 3 Adbi Baithak Gallery Exhibition Area حلقہء زن ج یر م یں ز باں م ت پھر کوئی آ با سر ق ل 11:00 am Urdu language and information technology Discussion on Qawwali Faiz ki shairi main umeed-o-yass 12:00 pm Dr Sarmad Hussain, Dr Agha Ali Raza, Zehra Nigah, Dr Arfa Syeda Dr. Amir Jafri Musharaf Ali Farooqi, Aamir Wali Children Activity (Qasim Jafri) (Sumera Khalil) ب ول (Dr Umar Saif) Children’s Debate competition Literature Schools Festival ی ڑھنے والوں کے بام طلسمات کے در بات کہاں پھہری ہے 12: 15 pm My journey theatre, TV, film The City - A site for history and identity Book launch: A Sentimental Journey ت pm Irfan Khoosat, Navid Shehzad, Samina Shatha Safi, Kamran Lashari Haroon Khalid, Anum Zakaria, Dr. Tahir 1:15 - کوئی صوی ر گائی رہی Peerzada, Samiya Mumtaz Dr Asma Ibrahim Kamran in conversation with Pran رات پھر Sarmad Khoosat) (Attiq Ahmed) Nevile) Photographic ص بح آزادی ق ق ہم تے سب شعر م یں سنوارے پھے کب کب ساق تا ! ر ص کوئی ر ص ص تا کی صورت years of Partition exhibition of Faiz 70 ھی ھی باد م یں ا پھرتے ہ یں - pm 1:30 Dance Performance Faiz ki shairi meiN naghmagii 2:30 pm Remembering Riaz Shahid Dr. -

New Sufi Sounds of Pakistan: Arif Lohar with Arooj Aftab

Asia Society and CaravanSerai Present New Sufi Sounds of Pakistan: Arif Lohar with Arooj Aftab Saturday, April 28, 2012, 8:00 P.M. Asia Society 725 Park Avenue at 70th Street New York City This program is 2 hours with no intermission New Sufi Sounds of Pakistan Performers Arooj Afab lead vocals Bhrigu Sahni acoustic guitar Jorn Bielfeldt percussion Arif Lohar lead vocals/chimta Qamar Abbas dholak Waqas Ali guitar Allah Ditta alghoza Shehzad Azim Ul Hassan dhol Shahid Kamal keyboard Nadeem Ul Hassan percussion/vocals Fozia vocals AROOJ AFTAB Arooj Aftab is a rising Pakistani-American vocalist who interprets mystcal Sufi poems and contemporizes the semi-classical musical traditions of Pakistan and India. Her music is reflective of thumri, a secular South Asian musical style colored by intricate ornamentation and romantic lyrics of love, loss, and longing. Arooj Aftab restyles the traditional music of her heritage for a sound that is minimalistic, contemplative, and delicate—a sound that she calls ―indigenous soul.‖ Accompanying her on guitar is Boston-based Bhrigu Sahni, a frequent collaborator, originally from India, and Jorn Bielfeldt on percussion. Arooj Aftab: vocals Bhrigu Sahni: guitar Jorn Bielfeldt: percussion Semi Classical Music This genre, classified in Pakistan and North India as light classical vocal music. Thumri and ghazal forms are at the core of the genre. Its primary theme is romantic — persuasive wooing, painful jealousy aroused by a philandering lover, pangs of separation, the ache of remembered pleasures, sweet anticipation of reunion, joyful union. Rooted in a sophisticated civilization that drew no line between eroticism and spirituality, this genre asserts a strong feminine identity in folk poetry laden with unabashed sensuality. -

Media Literacy Policy in Pakistan

Hacettepe University Graduate School of Social Sciences Department of Communication Sciences MEDIA LITERACY POLICY IN PAKISTAN Sana ZAINAB Master Thesis Ankara, 2019 MEDIA LITERACY POLICY IN PAKISTAN Sana ZAINAB Hacettepe University Graduate School of Social Sciences Department of Communication Sciences Master Thesis Ankara, 2019 YAYIMLAMA VE FİKRİ MÜLKİYET HAKLARI BEYANI Enstitü tarafından onaylanan lisansüstü tezimin tamamını veya herhangi bir kısmını, basılı (kağıt) ve elektronik formatta arşivleme ve aşağıda verilen koşullarla kullanıma açma iznini Hacettepe Üniversitesine verdiğimi bildiririm. Bu izinle Üniversiteye verilen kullanım hakları dışındaki tüm fikri mülkiyet haklarım bende kalacak, tezimin tamamının ya da bir bölümünün gelecekteki çalışmalarda (makale, kitap, lisans ve patent vb.) kullanım hakları bana ait olacaktır. Tezin kendi orijinal çalışmam olduğunu, başkalarının haklarını ihlal etmediğimi ve tezimin tek yetkili sahibi olduğumu beyan ve taahhüt ederim. Tezimde yer alan telif hakkı bulunan ve sahiplerinden yazılı izin alınarak kullanılması zorunlu metinleri yazılı izin alınarak kullandığımı ve istenildiğinde suretlerini Üniversiteye teslim etmeyi taahhüt ederim. Yükseköğretim Kurulu tarafından yayınlanan “Lisansüstü Tezlerin Elektronik Ortamda Toplanması, Düzenlenmesi ve Erişime Açılmasına İlişkin Yönerge” kapsamında tezim aşağıda belirtilen koşullar haricince YÖK Ulusal Tez Merkezi / H.Ü. Kütüphaneleri Açık Erişim Sisteminde erişime açılır. o Enstitü / Fakülte yönetim kurulu kararı ile tezimin erişime açılması mezuniyet -

ﮐﺴﯽ ﺑﮭﯽ اﻋﺘﺮاض ﮐﯽ ﺻﻮرت ﻣﯿﮟ ﻣﺘﻌﻠﻘہ ڈﺳﭩﺮﮐﭧ اﯾﺠﻮﮐﯿﺸﻦ آﻓﯿﺴﺮ ز ﮐﮯ دﻓﺎﺗﺮ اﭘﻨﯽ درﺧﻮاﺳﺖ داﺧﻞ ﮐﺮواﺋﯿﮟ اور ڈاﺋﺮی 56.988 14.8 3.672 10.306 ﻧﻤﺒﺮ ﻟﯿﻨﺎ ﻣﺖ8 9.4ﺑﮭﻮﻟﯿﮟ ۔ 4اس3

2/1/2017 Official Document Tentative List: Recruitment of Educators 201617, District KHANEWAL GMES CHUGHATA PUNJUANA, School's Name TULAMBA Post MIAN CHAUGHATA CHAUGHATA Authority DEO (Female) Name ESE Gender FEMALE Adv Sr # 125 Tehsil CHANNU School UC PUNJUANA Village PUNJUANA Prof. Total Diary # 17A UC Name Village Matric Intermediate Graduation Honors Master Diploma Qualification NTS Interview Marks Obtained Merit Candidate Name with Father Date of Out of # Priority # CNIC # / Husband Name Gender Birth Tehsil (Marks=10) (Marks=08) (Marks=04) (Marks=13) (Marks=15) (Marks=15) (Marks=30) (Marks=15) (Marks=10) (Marks=05) (Marks=20) (Marks=05) 100 1 2027 3610420572444 SUNDUS ANWAR Female 3004 MIAN 0 CHAUGHATA 786/1050 791/1100 548/800 754/1200 B.Ed 70 1991 CHANNU PUNJUANA (754/1250) 0 MUHAMMAD ANWAR 8 0 9.731 10.786 10.275 9.424 3.016 14 65.232 2 1405 3610474916150 SUMERA BASHIR Female 1103 MIAN 0 CHAUGHATA 650/850 683/1100 972/1500 853/1400 B.Ed 78 1988 CHANNU PUNJUANA (631/900) 0 BASHIR AHMED 8 0 9.941 9.313 9.72 9.139 3.505 15.6 65.218 3 1359 3610466992386 RASHIDA PARVEEN Female 0706 MIAN 0 CHAUGHATA 874/1050 768/1100 531/800 646/1200 B.Ed 66 1991 CHANNU PUNJUANA (747/1250) 0 NIAMAT ULLAH 8 0 10.82 10.472 9.956 8.074 2.988 13.2 63.51 4 474 3610497180298 ANAM SHAHZADI Female 0510 MIAN 0 625/850 869/1050 982/1500 1520/2000 B.Ed 73 1993 CHANNU (650/900) 0 MUHAMMAD IQBAL 0 0 9.558 12.414 9.82 11.4 3.611 14.6 61.403 5 2044 3650147545200 ROUBINA KOUSER Female 0104 MIAN 0 CHAUGHATA 19/8R 586/850 658/1100 493/800 547/1000 -

Book Review Essay Siren Song

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 21 Issue 6 Article 41 August 2020 Book Review Essay Siren Song Taimur Rahman Follow this and additional works at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Rahman, Taimur (2020). Book Review Essay Siren Song. Journal of International Women's Studies, 21(6), 516-519. Available at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol21/iss6/41 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2020 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Siren Song1 Reviewed by Taimur Rahman2 The title of this book is extremely misleading. This is not a book about siren songs. Or perhaps it is, but not in the way you think. The book draws you in, dressed as a biography of prominent Pakistani female singers. And then, you find yourself trapped into a complex discussion of post-colonial philosophy stretching across time (in terms of philosophy) and space (in terms of continents). Hence, any review of this book cannot be a simple retelling of its contents but begs the reader to engage in some seriously strenuous thinking. I begin my review, therefore, not with what is in, but with what is not in the book - the debate that shapes the book, and to which this book is a stimulating response. -

History, Narrative, and the Female Figure (As Disruption) / Rizvi 35 Guises Himself in Jayida’S Clothes to Deceive Her Husband

Shahzia Sikander began studying painting at the National of great artists. Like poetry, paintings were incorporated College of Arts in Lahore, working closely with Bashir into the performative rituals of the court, where the Ahmad, a master of the art of manuscript illustration. The cognoscenti gathered to admire and evaluate the works History, Narrative, “miniature,” as the genre he taught is sometimes referred of art. to, places Sikander’s work in a lineage that is at once Lahore was well known in the sixteenth and sev- local and historically grounded. Although once perceived enteenth centuries as one of the capitals of the Mughal and the by Euro-American scholars as conventional and repeti- Empire, with a magnificent fort, mosques, and gardens. tive, early modern illustrated manuscripts and drawings— The imperial household included talented scribes, poets, the foundation of Sikander’s practice—are now under- and artists from across India. Among the most well Female Figure stood to be a platform for innovation and artistic virtuos- known were Miskin (active ca. 1580–1604) and Basawan ity. Her paintings are in fact imbedded within a complex (active ca. 1580–1600), both of whom were extolled by tradition of art-making, with its strategies of allegory, narration, and appropriation. They build on past prece- dents and are made contemporary through their subject matter and through her rendition, scaled up or down and translated to other media, such as animation. Sikander’s perspective is informed by the social, political, and reli- gious cultures of her home in Lahore, while reflecting her participation in the broader art world of New York, her current residence. -

Research and Development

Annual Report 2010-11 Research and Development RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT FACULTY OF ARTS & HUMANITIES DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY Projects: (i) Completed UNESCO funded project ―Sui Vihar Excavations and Archaeological Reconnaissance of Southern Punjab” has been completed. Research Collaboration Funding grants for R&D o Pakistan National Commission for UNESCO approved project amounting to Rs. 0.26 million. DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE & LITERATURE Publications Book o Spatial Constructs in Alamgir Hashmi‘s Poetry: A Critical Study by Amra Raza Lambert Academic Publishing, Germany 2011 Conferences, Seminars and Workshops, etc. o Workshop on Creative Writing by Rizwan Akthar, Departmental Ph.D Scholar in Essex, October 11th , 2010, Department of English Language & Literature, University of the Punjab, Lahore. o Seminar on Fullbrght Scholarship Requisites by Mehreen Noon, October 21st, 2010, Department of English Language & Literature, Universsity of the Punjab, Lahore. Research Journals Department of English publishes annually two Journals: o Journal of Research (Humanities) HEC recognized ‗Z‘ Category o Journal of English Studies Research Collaboration Foreign Linkages St. Andrews University, Scotland DEPARTMENT OF FRENCH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE R & D-An Overview A Research Wing was introduced with its various operating desks. In its first phase a Translation Desk was launched: Translation desk (French – English/Urdu and vice versa): o Professional / legal documents; Regular / personal documents; o Latest research papers, articles and reviews; 39 Annual Report 2010-11 Research and Development The translation desk aims to provide authentic translation services to the public sector and to facilitate mutual collaboration at international level especially with the French counterparts. It addresses various businesses and multi national companies, online sales and advertisements, and those who plan to pursue higher education abroad. -

Pop Compact Disc Releases - Updated 08/29/21

2011 UNIVERSITY AVENUE BERKELEY, CA 94704, USA TEL: 510.548.6220 www.shrimatis.com FAX: 510.548.1838 PRICES & TERMS SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE INTERNATIONAL ORDERS ARE NOW ACCEPTED INTERNATIONAL ORDERS ARE GENERALLY SHIPPED THRU THE U.S. POSTAL SERVICE. CHARGES VARY BY COUNTRY. WE WILL ALWAYS COMPARE VARIOUS METHODS OF SHIPMENT TO KEEP THE SHIPPING COST AS LOW AS POSSIBLE PAYMENT FOR ORDERS MUST BE MADE BY CREDIT CARD PLEASE NOTE - ALL ITEMS ARE LIMITED TO STOCK ON HAND POP COMPACT DISC RELEASES - UPDATED 08/29/21 Pop LABEL: AAROHI PRODUCTIONS $7.66 APCD 001 Rawals (Hitesh, Paras & Rupesh) "Pehli Nazar" / Pehli Nazar, Meri Nigahon Me, Aaja Aaja, Me Dil Hu, Tujhko Banaya, Tujhko Banaya (Sad), Humne Tumko, Oh Hasina, Me Tera Hu Diwana (ADD) LABEL: AUDIOREC $6.99 ARCD 2017 Shreeti "Mere Sapano Mein" (Music: Rajesh Tailor) Mere Sapano Mein, Jatey Jatey, Ek Khat, Teri Dosti, Jaan E Jaan, Tumhara Dil - 2 Versions, Shehenayi Ke Soor, Chalte Chalte, Instrumental (ADD) $6.99 ARCD 2082 Bali Brahmbhatt "Sparks of Love" / Karle Tu Reggae Reggae, O Sanam, Just Between You N Me, Mere Humdum, Jaana O Meri Jaana, Disco Ho Ya Reggae, Jhoom Jhoom Chak Chak, Pyar Ke Rang, Aag Ke Bina Dhuan Nahin, Ja Rahe Ho / Introducing Jayshree Gohil (ADD) LABEL: AVS MUSIC $3.99 AVS 001 Anamika "Kamaal Ho Gaya" / Kamaal Ho Gaya, Nach Lain De, Dhola Dhol, Badhai Ho Badhai, Beetiyan Kahaniyan, Aa Bhi Ja, Kahaan Le Gayee, You & Me LABEL: BMG CRESCENDO (BUDGET) $6.99 CD 40139 Keh Diya Pyar Se / Lucky Ali - O Sanam / Vikas Bhalla - Dhuan, Keh Diya Pyar Se / Anaida - -

Copyright by Mohammad Raisur Rahman 2008

Copyright by Mohammad Raisur Rahman 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Mohammad Raisur Rahman certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Islam, Modernity, and Educated Muslims: A History of Qasbahs in Colonial India Committee: _____________________________________ Gail Minault, Supervisor _____________________________________ Cynthia M. Talbot _____________________________________ Denise A. Spellberg _____________________________________ Michael H. Fisher _____________________________________ Syed Akbar Hyder Islam, Modernity, and Educated Muslims: A History of Qasbahs in Colonial India by Mohammad Raisur Rahman, B.A. Honors; M.A.; M.Phil. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2008 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to the fond memories of my parents, Najma Bano and Azizur Rahman, and to Kulsum Acknowledgements Many people have assisted me in the completion of this project. This work could not have taken its current shape in the absence of their contributions. I thank them all. First and foremost, I owe my greatest debt of gratitude to my advisor Gail Minault for her guidance and assistance. I am grateful for her useful comments, sharp criticisms, and invaluable suggestions on the earlier drafts, and for her constant encouragement, support, and generous time throughout my doctoral work. I must add that it was her path breaking scholarship in South Asian Islam that inspired me to come to Austin, Texas all the way from New Delhi, India. While it brought me an opportunity to work under her supervision, I benefited myself further at the prospect of working with some of the finest scholars and excellent human beings I have ever known. -

Music- a Literary Social Science

International Research Journal of Social Sciences_____________________________________ ISSN 2319–3565 Vol. 2(4), 28-30, April (2013) Int. Res. J. Social Sci. Music- A Literary Social Science Shivadurga and Mehrotra Vivek English Department, Institute of Applied Science and Humanities, GLA University, Mathura, UP, INDIA Available online at: www.isca.in Received 22 nd November 2012, revised 20 th December 2013, accepted 28 th February 2013 Abstract Music is the movement of sound to reach the soul for the education of its virtue.The study of music is a part of biology as the study of living organisms. Music exists because people create it, perform it and listen to it. The human brain is an information processing system. Music is a higher revelation than all wisdom and philosophy. Music is a super-stimulus to express the strong emotions about the internal mental state of the speaker. The musicality of speech is much more subtle than that of music, but it provides important information which the listener's brain processes in order to derive some information. This information is applied to modulate the listener's emotional response to speech, and this accounts for the emotional effect of music. The normal function of the cortical map that responds to consonant relationships between different notes occurring at the same time within harmonies and chords must be the perception of consonant relationships between pitch values occurring at different times within the same speech melody. There are at least five and possibly six symmetries of music like: Pitch translation invariance, Time translation invariance, Time scaling invariance, Amplitude scaling invariance, Octave translation invariance and Pitch reflection invariance. -

Ky; Okf”Kzd Izfrosnu

2013-14 tokgjyky usg# fo’ofo|ky; Jawaharlal Nehru University okf”kZd izfrosnu 44 Annual Report Contents THE LEGEND 1 ACADEMIC PROGRAMMES AND ADMISSIONS 5 UNIVERSITY BODIES 10 SCHOOLS AND CENTRES 19-302 School of Arts and Aesthetics (SA&A) 19 School of Biotechnology (SBT) 35 School of Computational and Integrative Sciences (SCIS) 40 School of Computer & Systems Sciences (SC&SS) 45 School of Environmental Sciences (SES) 51 School of International Studies (SIS) 60 School of Language, Literature & Culture Studies (SLL&CS) 101 School of Life Sciences (SLS) 136 School of Physical Sciences (SPS) 154 School of Social Sciences (SSS) 162 Centre for the Study of Law & Governance (CSLG) 281 Special Centre for Molecular Medicine (SCMM) 292 Special Centre for Sanskrit Studies (SCSS) 297 ACADEMIC STAFF COLLEGE 303 STUDENT’S ACTIVITIES 312 ENSURING EQUALITY 320 LINGUISTIC EMPOWERMENT CELL 324 UNIVERSITY ADMINISTRATION 327 CAMPUS DEVELOPMENT 331 UNIVERSITY FINANCE 332 OTHER ACTIVITIES 334-341 Gender Sensitisation Committee Against Sexual Harassment 334 Alumni Affairs 336 Jawaharlal Nehru Institute of Advanced Studies 336 International Collaborations 340 CENTRAL FACILITIES 342-370 University Library 342 University Science Instrumentation Centre 358 Advanced Instrumentation Research Facility 360 University Employment Information & Guidance Bureau 370 JNU Annual Report 2012-13 iii FACULTY PUBLICATIONS 371-463 FACULTY RESEARCH PROJECTS 464-482 ANNEXURES 483-574 MEMBERSHIP OF UNIVERSITY BODIES 483 University Court 483 Executive Council 489 Academic Council 490 Finance Committee 495 TEACHERS 496 Faculty Members 496 Emeritus/Honorary Professors 509 Faculty Members Appointed 510 Faculty Members Confirmed 512 Faculty Members Resigned 512 Faculty Members Retired Compulsorily 513 Faculty Members Retired Superannuation 513 Faculty members Re-employed 513 RESEARCH SCHOLARS 514-574 Ph.D.