Mao Zedong Volume 1: 1893–1949 Excerpt More Information

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glottal Stop Initials and Nasalization in Sino-Vietnamese and Southern Chinese

Glottal Stop Initials and Nasalization in Sino-Vietnamese and Southern Chinese Grainger Lanneau A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Washington 2020 Committee: Zev Handel William Boltz Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Asian Languages and Literature ©Copyright 2020 Grainger Lanneau University of Washington Abstract Glottal Stop Initials and Nasalization in Sino-Vietnamese and Southern Chinese Grainger Lanneau Chair of Supervisory Committee: Professor Zev Handel Asian Languages and Literature Middle Chinese glottal stop Ying [ʔ-] initials usually develop into zero initials with rare occasions of nasalization in modern day Sinitic1 languages and Sino-Vietnamese. Scholars such as Edwin Pullyblank (1984) and Jiang Jialu (2011) have briefly mentioned this development but have not yet thoroughly investigated it. There are approximately 26 Sino-Vietnamese words2 with Ying- initials that nasalize. Scholars such as John Phan (2013: 2016) and Hilario deSousa (2016) argue that Sino-Vietnamese in part comes from a spoken interaction between Việt-Mường and Chinese speakers in Annam speaking a variety of Chinese called Annamese Middle Chinese AMC, part of a larger dialect continuum called Southwestern Middle Chinese SMC. Phan and deSousa also claim that SMC developed into dialects spoken 1 I will use the terms “Sinitic” and “Chinese” interchangeably to refer to languages and speakers of the Sinitic branch of the Sino-Tibetan language family. 2 For the sake of simplicity, I shall refer to free and bound morphemes alike as “words.” 1 in Southwestern China today (Phan, Desousa: 2016). Using data of dialects mentioned by Phan and deSousa in their hypothesis, this study investigates initial nasalization in Ying-initial words in Southwestern Chinese Languages and in the 26 Sino-Vietnamese words. -

Hunan Flood Management Sector Project

Social Monitoring Report Project Number: 37641 May 2009 PRC: Hunan Flood Management Sector Project External Monitoring and Evaluation Report on Resettlement (Prepared by Changsha Xinghuan Water & Electricty Engineering Technology Development Co.) No.4 Prepared by Changsha Xinghuan Water & Electricity Engineering Technology Development Co., Changsha City, Hunan Province, People's Republic of China For the Hunan Provincial Water Resources Department This report has been submitted to ADB by the Hunan Provincial Water Resources Department and is made publicly available in accordance with ADB’s public communications policy (2005). It does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB. Loan No.: 2244-PRC Hunan Flood Control Project for Hilly Areas Utilizing ADB Loans Resettlement External Monitoring & Evaluation Report (No. 4) Changsha Xinghuan Water & Electricity Engineering Technology Development Co., Ltd. Apr. 2009 Chief Supervisor: Qin Lin Deputy Chief Supervisor: Huang Qingyun Chen Zizhou Compiler: Huang Qingyun Chen Zizhou Qin Si Li Yuntao Min Tian Qin Lin Main Working Staff: Qin Lin Huang Qingyun Chen Zizhou Qin Si Li Yuntao Min Tian Xia Jihong Ren Yu Li Jianwu Li Tiehui Resettlement External Monitoring & Evaluation Report on the Hunan Flood Control Project for Hilly Areas Utilizing ADB Loans Contents 1. Monitoring & Evaluation Tasks and Implementations of this Period...........................2 2. Project Description...........................................................................................................3 3. Construction -

The Secretary for Home Affairs, Mr Tsang Tak-Sing, Encouraged The

Guangdong-HK-Macao youth cultural programme promotes exchanges ********************************************************* The Secretary for Home Affairs, Mr Tsang Tak-sing, encouraged young people from Guangdong, Hong Kong and Macao to consolidate the invaluable experiences gained from the 2010 Guangdong-HK-Macao Youth Cultural Exchange Tour to further strengthen co-operation and explore wider scope for exchanges. Mr Tsang witnessed around 130 young people completing this meaningful programme at the closing ceremony held in Guangzhou today (July 20). He said he was glad to know that the young participants had not only made acquaintances during the eight-day tour, but had also learned about the background and preservation of the cultures in the three places. With the theme "Culture Links Friendship", this year's tour enriched participants' understanding of the cultures of the three places through excursions and cultural seminars. "The 11th Greater Pearl River Delta Cultural Co-operation Meeting was held on June 25 in Macao. There were fruitful developments on exchanges of artists and information, cultural programme and library collaboration, intangible cultural heritages as well as development of the cultural and creative industry," Mr Tsang said. "And yet, the future growth of the arts and culture in Guangzhou, Hong Kong and Macao hinges much on young people's passion and innovation. Thus, apart from forming new friendships among the participants, I hope this tour will also help broaden their horizons and lay a solid foundation for further co-operation and exchange in the arts and culture among the three places in future," he added. The nine-day Guangdong-HK-Macao Youth Cultural Tour was co-organised by the Home Affairs Bureau of the HKSAR, the Department of Culture of Guangdong Province and the Tertiary Education Services Office of Macao SAR. -

Corporate Social Responsibility White Paper

2020 CEIBS CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY WHITE PAPER FOREWORD The Covid-19 pandemic has brought mounting research teams, as well as alumni associations and com- uncertainties and complexities to the world economy. Our panies. The professors obtained the research presented globalized society faces the challenge of bringing the in the paper through the employment of detailed CSR virus under control while minimizing its impact on the parameters focused on business leaders, employee economy. Economic difficulties substantially heighten the behavior and their relationship to the external environ- urgency for a more equitable and sustainable society. ment. This granular and nuanced form of research is a powerful tool for guiding the healthy development of CSR. At the same time, there is an ever-pressing need to enrich and expand the CSR framework in the context of The five CEIBS alumni companies featured in the social and economic development. CEIBS has incorporat- white paper offer exceptional examples of aligning busi- ed CSR programs into teaching, research, and student/ ness practices with social needs. Their learning-based alumni activities since its inception. The international busi- future-proof business innovations are a powerful demon- ness school jointly founded by the Chinese government stration of how best to bring CSR to the forefront of busi- and the European Union has accelerated knowledge ness activities. These five firms all received the CSR creation and dissemination during the pandemic to sup- Award in April 2019 at the second CEIBS Alumni Corpo- port economic stability and business development. The rate Social Responsibility Award, organized by the CEIBS institution has also served as a key communication chan- Alumni Association. -

The Darkest Red Corner Matthew James Brazil

The Darkest Red Corner Chinese Communist Intelligence and Its Place in the Party, 1926-1945 Matthew James Brazil A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Doctor of Philosophy Department of Government and International Relations Business School University of Sydney 17 December 2012 Statement of Originality This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted previously, either in its entirety or substantially, for a higher degree or qualifications at any other university or institute of higher learning. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources has been acknowledged. Matthew James Brazil i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Before and during this project I met a number of people who, directly or otherwise, encouraged my belief that Chinese Communist intelligence was not too difficult a subject for academic study. Michael Dutton and Scot Tanner provided invaluable direction at the very beginning. James Mulvenon requires special thanks for regular encouragement over the years and generosity with his time, guidance, and library. Richard Corsa, Monte Bullard, Tom Andrukonis, Robert W. Rice, Bill Weinstein, Roderick MacFarquhar, the late Frank Holober, Dave Small, Moray Taylor Smith, David Shambaugh, Steven Wadley, Roger Faligot, Jean Hung and the staff at the Universities Service Centre in Hong Kong, and the kind personnel at the KMT Archives in Taipei are the others who can be named. Three former US diplomats cannot, though their generosity helped my understanding of links between modern PRC intelligence operations and those before 1949. -

Hunan Flood Management Sector Project: Xiangtan City Resettlement

Resettlement Plan December 2014 PRC: Hunan Flood Management Sector Project Resettlement Plan and Due Diligence Report for Xiangtan City (Non-Core Subproject) Prepared by Hunan Hydro and Power Design Institute for the Hunan Provincial Project Management Office (PMO) of Urban Flood Control Project in Hilly Region Utilizing ADB Loans, Xiangtan City PMO of Urban Flood Control Project Utilizing ADB Loans, and the Asian Development Bank. GSDS Certificate Grade A No.180105-sj GSDK Certificate Grade A No.180105-kj GZ Certificate Grade A No. 1032523001 SBZ Certificate Grade A No. 027 Hunan Province Xiangtan City Urban Flood Control Project Utilizing ADB Loans Resettlement Plan and Due Diligence Report (Final version) Hunan Provincial PMO of Urban Flood Control Project in Hilly Region Utilizing ADB Loans Xiangtan City PMO of Urban Flood Control Project Utilizing ADB Loans Hunan Hydro and Power Design Institute December, 2014 i Approved by : Xiao Wenhui Ratified by: Zhang Kejian Examined by: Xie Dahu Checked by: Tan Lu Compiled by: Liu Hongyan Main Designers: Ouyang Xiongbiao Guan Yaohui Zhao Gengqiang Tan Lu Liu Hongyan Teng Yan Zhou Kai Jin Hongli Huang Bichen ii Contents Updated Info……………………………………………………………………………………………………………i Objectives of Resettlement Plan & Definition of Resettlement Vocabulary……………………………….1 Executive Summary .....................................................................................................................................3 A. STATUS OF RESETTLEMENT PLAN .................................................................................................................................... -

September 27, 1972 Excerpt of Mao Zedong's Conversation With

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified September 27, 1972 Excerpt of Mao Zedong’s Conversation with Japanese Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka Citation: “Excerpt of Mao Zedong’s Conversation with Japanese Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka,” September 27, 1972, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Chinese Communist Party Central Archives. Translated by Caixia Lu. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/118567 Summary: Mao claims that, as a result of Tanaka's visit to China, "the whole world is trembling in fear." In addition to discussing international politics, Mao and Tanaka also delve into ancient Chinese history and Buddhist philosophy. Credits: This document was made possible with support from the MacArthur Foundation. Original Language: Chinese Contents: English Translation Excerpt of Mao Zedong’s Conversation with Japanese Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka 27 September 1972 Chairman Mao: With your [the Japanese] visit to Beijing, the whole world is trembling in fear, mainly one Soviet Union and one United States, the two big powers. They are fairly uneasy, and wondering what you [the Japanese] are up to. Tanaka: The United States has declared its support for our visit to China. Chairman Mao: The United States is slightly better, but they are also feeling a little uncomfortable. [They] said that they didn’t manage to establish diplomatic relations during their visit in February this year and that you [the Japanese] had run ahead of them. Well, they are just feeling a little unhappy about it somehow. Tanaka: On the surface, the Americans are still very friendly to us. Chairman Mao: Yes, Kissinger had also informed us: Don’t set barriers. -

The Embodiment of Transforming Gender and Class: Shengnu and Their Media Representation in Contemporary China

THE EMBODIMENT OF TRANSFORMING GENDER AND CLASS: SHENGNU AND THEIR MEDIA REPRESENTATION IN CONTEMPORARY CHINA By Zhou Chen Submitted to the graduate degree program in Anthropology and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts ________________________________ Dr. Akiko Takeyama, Chairperson ________________________________ Dr. Allan Hanson ________________________________ Dr. Hui Xiao Date Defended: July.27.2011 The Thesis Committee for Zhou Chen Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: THE EMBODIMENT OF TRANSFORMING GENDER AND CLASS: SHENGNU AND THEIR MEDIA REPRESENTATION IN CONTEMPORARY CHINA ________________________________ Dr. Akiko Takeyama, Chairperson Date approved: July.27.2011 II ABSTRACT Zhou Chen Department of Anthropology University of Kansas 2011 This thesis examines a large number of middle class, single, career women in China’s metropolises. They are sensationalized and problematized as Shengnü (left-over women) by popular newspapers and magazines. Empowered by the market economy and Western vision mass media displays, they hold new expectations in relationship and future marriage. Meanwhile, their prospective conflicts with the social ideal of women: a “good wife wise mother” with a job. This failure of fitting the ideal is socially constructed by the socioeconomic complexity, because their whole identity and routine of life is also determined by the current development trend. Young Chinese including Shengnü, who pursue the maximum personal benefits, are conducted to cluster in limited residences, industries and occupations. This development mode is also male-centric and devalues women’s domestic contribution. Particularly, Shengnü are constructed to be self-interested middle class and materialists by intersecting political agenda and mass media. -

Copyright by James Joshua Hudson 2015

Copyright by James Joshua Hudson 2015 The Dissertation Committee for James Joshua Hudson Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: River Sands/Urban Spaces: Changsha in Modern Chinese History Committee: Huaiyin Li, Supervisor Mark Metzler Mary Neuburger David Sena William Hurst River Sands/Urban Spaces: Changsha in Modern Chinese History by James Joshua Hudson, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2015 Dedication For my good friend Hou Xiaohua River Sands/Urban Spaces: Changsha in Modern Chinese History James Joshua Hudson, PhD. The University of Texas at Austin, 2015 Supervisor: Huaiyin Li This work is a modern history of Changsha, the capital city of Hunan province, from the late nineteenth to mid twentieth centuries. The story begins by discussing a battle that occurred in the city during the Taiping Rebellion (1850-1864), a civil war that erupted in China during the mid nineteenth century. The events of this battle, but especially its memorialization in local temples in the years following the rebellion, established a local identity of resistance to Christianity and western imperialism. By the 1890’s this culture of resistance contributed to a series of riots that erupted in south China, related to the distribution of anti-Christian tracts and placards from publishing houses in Changsha. During these years a local gentry named Ye Dehui (1864-1927) emerged as a prominent businessman, grain merchant, and community leader. -

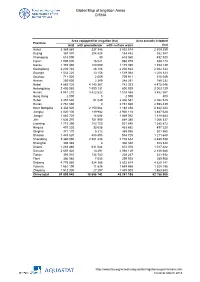

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA Area equipped for irrigation (ha) Area actually irrigated Province total with groundwater with surface water (ha) Anhui 3 369 860 337 346 3 032 514 2 309 259 Beijing 367 870 204 428 163 442 352 387 Chongqing 618 090 30 618 060 432 520 Fujian 1 005 000 16 021 988 979 938 174 Gansu 1 355 480 180 090 1 175 390 1 153 139 Guangdong 2 230 740 28 106 2 202 634 2 042 344 Guangxi 1 532 220 13 156 1 519 064 1 208 323 Guizhou 711 920 2 009 709 911 515 049 Hainan 250 600 2 349 248 251 189 232 Hebei 4 885 720 4 143 367 742 353 4 475 046 Heilongjiang 2 400 060 1 599 131 800 929 2 003 129 Henan 4 941 210 3 422 622 1 518 588 3 862 567 Hong Kong 2 000 0 2 000 800 Hubei 2 457 630 51 049 2 406 581 2 082 525 Hunan 2 761 660 0 2 761 660 2 598 439 Inner Mongolia 3 332 520 2 150 064 1 182 456 2 842 223 Jiangsu 4 020 100 119 982 3 900 118 3 487 628 Jiangxi 1 883 720 14 688 1 869 032 1 818 684 Jilin 1 636 370 751 990 884 380 1 066 337 Liaoning 1 715 390 783 750 931 640 1 385 872 Ningxia 497 220 33 538 463 682 497 220 Qinghai 371 170 5 212 365 958 301 560 Shaanxi 1 443 620 488 895 954 725 1 211 648 Shandong 5 360 090 2 581 448 2 778 642 4 485 538 Shanghai 308 340 0 308 340 308 340 Shanxi 1 283 460 611 084 672 376 1 017 422 Sichuan 2 607 420 13 291 2 594 129 2 140 680 Tianjin 393 010 134 743 258 267 321 932 Tibet 306 980 7 055 299 925 289 908 Xinjiang 4 776 980 924 366 3 852 614 4 629 141 Yunnan 1 561 190 11 635 1 549 555 1 328 186 Zhejiang 1 512 300 27 297 1 485 003 1 463 653 China total 61 899 940 18 658 742 43 241 198 52 -

Effectiveness of Live Poultry Market Interventions on Human Infection with Avian Influenza A(H7N9) Virus, China Wei Wang,1 Jean Artois,1 Xiling Wang, Adam J

RESEARCH Effectiveness of Live Poultry Market Interventions on Human Infection with Avian Influenza A(H7N9) Virus, China Wei Wang,1 Jean Artois,1 Xiling Wang, Adam J. Kucharski, Yao Pei, Xin Tong, Victor Virlogeux, Peng Wu, Benjamin J. Cowling, Marius Gilbert,2 Hongjie Yu2 September 2017) as of March 2, 2018 (2). Compared Various interventions for live poultry markets (LPMs) have with the previous 4 epidemic waves, the 2016–17 fifth emerged to control outbreaks of avian influenza A(H7N9) virus in mainland China since March 2013. We assessed wave raised global concerns because of several char- the effectiveness of various LPM interventions in reduc- acteristics. First, a surge in laboratory-confirmed cas- ing transmission of H7N9 virus across 5 annual waves es of H7N9 virus infection was observed in wave 5, during 2013–2018, especially in the final wave. With along with some clusters of limited human-to-human the exception of waves 1 and 4, various LPM interven- transmission (3,4). Second, a highly pathogenic avi- tions reduced daily incidence rates significantly across an influenza H7N9 virus infection was confirmed in waves. Four LPM interventions led to a mean reduction Guangdong Province and has caused further human of 34%–98% in the daily number of infections in wave 5. infections in 3 provinces (5,6). The genetic divergence Of these, permanent closure provided the most effective of H7N9 virus, its geographic spread (7), and a much reduction in human infection with H7N9 virus, followed longer epidemic duration raised concerns about an by long-period, short-period, and recursive closures in enhanced potential pandemic threat in 2016–17. -

Industry and Regulatory Overview

INDUSTRY AND REGULATORY OVERVIEW Unless otherwise indicated, the information in the section below has been derived, in part, from various official government publications. We believe that the sources of this information are appropriate sources for such information and have taken reasonable care in extracting and reproducing such information. We have no reason to believe that such information is false or misleading or that any fact has been omitted that would render such information false or misleading. The information has not been independently verified by us, the Sponsor, the Bookrunner, the Lead Manager, the Underwriters, any of their respective directors, officers or representatives, or any other party involved in the Share Offer and no representation is given as to its accuracy. Industry Overview 1. THE ECONOMY OF CHINA AND HUNAN PROVINCE Hunan, strategically located in central China with connectivity to all directions, is a major resources and product interchange centre and transport hub in China. According to “Opinions of the CPC Central Committee and the State Council on the Promotion of the Rise of the Central Region” (Zhong Fa No.10 (2006)) (《中共中央國務院關於促進中部地區崛起的 若干意見》(中發 [2006]10號)), by carrying out strategies to promote the rise of the central region, the State clearly requested to develop the central region of China into major “three bases and one hub” of the country, namely stable food production base, energy and raw materials base, high-tech industry and modern equipment manufacturing base, and integrated transport hub. At