Notes Preface

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C 1992-219 a Nahuatl Interpretation of the Conquest

In: Amaryll Chanady, Latin American Identity and Constructions of Difference, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, Vol. 10, 1994, pp. 104-129. Chapter 6 A Nahuatl Interpretation of the Conquest: From the "Parousia" of the Gods to the "Invasion" Enrique Dussel (translated by Amaryll Chanady) In teteu inan in tetu ita, in Huehueteutl [Mother of the gods, Father of the gods, the Old God], lying on the navel of the Earth, enclosed in a refuge of turquoises. He who lives in the waters the color of a blue bird, he who is surrounded by clouds, the Old God, he who lives in the shadows of the realm of the dead, the lord of fire and time. -Song to Ometeótl, the originary being of the Aztec Tlamatinime1 I would like to examine the "meaning of 1492," which is nothing else but "the first experience of modem Europeans," from the perspective of the "world" of the Aztecs, as the conquest in the literal sense of the term started in Mexico. In some cases I will refer to other cultures in order to suggest additional interpreta- tions, although I am aware that these are only a few of the many possible examples, and that they are a mere "indication" of the problematic. Also, in the desire to continue an intercultural dia- logue initiated in Freiburg with Karl-Otto Apel in 1989, I will re- fer primarily to the existence of reflexive abstract thought on our continent.2 The tlamatini In nomadic societies (of the first level) or societies of rural plant- ers (like the Guaranis), social differentiation was not developed sufficiently to identify a function akin to that of the "philoso- pher", although in urban society this social figure acquires a dis- tinct profile.3 As we can read in Garcilaso de la Vega's Comenta- rios reales de los Incas: 104 105 Demás de adorar al Sol por dios visible, a quien ofrecieron sacrificios e hicieron grandes fiestas,.. -

Mexico and Spain on the Eve of Encounter

4 Mexico and Spain on the Eve of Encounter In comparative history, the challenge is to identify significant factors and the ways in which they are related to observed outcomes. A willingness to draw on historical data from both sides of the Atlantic Ocean will be essen- tial in meeting this challenge. — Walter Scheidel (2016)1 uring the decade before Spain’s 1492 dynastic merger and launching of Dtrans- Atlantic expeditions, both the Aztec Triple Alliance and the joint kingdoms of Castile and Aragón were expanding their domains through con- quest. During the 1480s, the Aztec Empire gained its farthest flung province in the Soconusco region, located over 500 miles (800 km) from the Basin of Mexico near the current border between Mexico and Guatemala. It was brought into the imperial domain of the Triple Alliance by the Great Speaker Ahuitzotl, who ruled from Tenochtitlan, and his younger ally and son- in- law Nezahualpilli, of Texcoco. At the same time in Spain, the allied Catholic Monarchs Isabela of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragón were busy with military campaigns against the southern emirate of Granada, situated nearly the same distance from the Castilian heartland as was the Soconusco from the Aztec heartland. The unification of the kingdoms ruled by Isabela and Ferdinand was in some sense akin to the reunifi- cation of Hispania Ulterior and Hispania Citerior of the early Roman period.2 The conquest states of Aztec period Mexico and early modern Spain were the product of myriad, layered cultural and historical processes and exchanges. Both were, of course, ignorant of one another, but the preceding millennia of societal developments in Mesoamerica and Iberia set the stage for their momentous en- counter of the sixteenth century. -

Hispanic/Latino Issues in Philosophy

APA NEWSLETTER ON Hispanic/Latino Issues in Philosophy Eduardo Mendieta, Editor Spring 2004 Volume 03, Number 2 REPORT FROM THE CHAIR ARTICLES January 23, 2004 The Epistemology of Aztec Time-Keeping I am pleased to announce that the efforts of the Committee James Maffie on Hispanics toward establishing an annual prize for scholarly Colorado State University work in Latin American philosophy have been successful: the prize will soon be a reality, thanks to the APA’s recent decision Pre-Columbian Aztec (Mexica) astronomy achieved to support it for an initial period of three years. We plan to remarkable empirical accuracy, predictive success, and offer the prize once a year, at the Eastern Division meeting of mathematical precision.1 Aztec astronomers believed the the association, beginning this year in Boston. Those interested movement of time through space to be the self-presenting of in applying should be sure to check the conditions, which are the sacred. They followed celestial and terrestrial patterns, listed in this issue of the Newsletter. with an eye towards predicting the future, proper human ritual I would also like to report that we have continued moving participation and living in harmony with the cosmos, and ahead full-steam to promote Latin American philosophy, to understanding sacred reality. raise the profile of Hispanics in the profession, and to defend I want to examine two puzzles regarding Aztec astronomy. their rights. The Committee had a crucial role in the success of First, Aztec epistemology maintained that humans attain the first annual symposium on Latin American philosophy, held knowledge of reality a priori using their yollo (“heart”), not at Texas State University in San Marcos in October 2003. -

Enrique Dussel, and Jus- Tus George Lawler of Continuum for His Continued Interest in This Project

4 Contents Translator's Acknowledgements 7 Preface 9 PART ONE From the European Ego: The Covering Over ● 15 Chapter 1: Eurocentrism 19 Chapter 2: From the Invention to the Discovery of the New World 27 Chapter 3: From the Conquest to the Colonization of the Life- World 37 Chapter 4 : The Spiritual Conquest: Toward the Encounter between Two Worlds? 49 PART TWO Transition: The Copernican Revolution of the Hermeneutic Key ● 59 Chapter 5: Critique of the Myth of Modernity 63 Chapter 6: Amerindia in a Non-Eurocentric Vision of World History 73 5 PART THREE From the Invasion to the Dis-covery of the Other ● 91 Chapter 7: From the Parousia of the Gods to the Invasion 95 Chapter 8: From the Resistance to the End of the World and the Sixth Sun 106 Epilogue: The Multiple Visages of the One People and the Sixth Sun 119 Appendix 1: Diverse Meanings of the Terms Europe, The Occident, Modernity, Late Capitalism 133 Appendix 2: Two Paradigms of Modernity 136 Appendix 3: From the Discovery of the Atlantic to 1502 141 Appendix 4: Map of the Fourth Asiatic Peninsula of Henry Martellus (Florence 1489) 142 Notes 145 Chronology 211 Index 214 6 Translator's Acknowledgments The translator would like to thank Enrique Dussel, and Jus- tus George Lawler of Continuum for his continued interest in this project. Thanks are due also to Mrs. Virginia Duck- worth for editing assistance and Mr. Ollie L. Roundtree for techni- cal assistance. I have translated the German texts (e.g., from Kant, Hegel, Marx) on the basis of Dussel's Spanish translations of those texts, since he frequently utilizes ellipses to omit several pages and since other En- glish translations of these texts would not adequately convey Dus- sel's own reasons for combining such texts in a single quotation. -

Reciprocity, Balance and Nepantla in Aztec Ethics

Science, Religion & Culture Article Special Issue: Cross-Cultural Studies in Well-Being Weaving the Good Life in a Living World: Reciprocity, Balance and Nepantla in Aztec Ethics James Maffie Department of American Studies, 1328 Tawes Hall, University of Maryland,College Park, MD 20740 Abstract | The Aztecs saw themselves living in a world that was not only inherently unstable but also inexorably destined to succumb to imbalance-induced total destruction. They perceived human beings’ hold on life in these circumstances as inescapably “slippery” and thus fraught with hardship, pain, suffering, sorrow, hunger, disease, and death. Stubbornly refusing to surrender to despair, Aztec philosophers (tlamatinimeh) responded with what they called toltecayotl or “the art of living wisely and well.” Toltecayotl enjoined humans to pursue balance in all matters, ranging from how they treated themselves and other humans to how they treated the countless other-than-human agents populating their living world. Humans attained balance in two principal ways, both of which Aztec philosophers understood in terms of the indigenous concept of a nepantla process, a paradigmatic ex- ample of which was the artisanal process of weaving. Humans accordingly attained balance: first, by weaving together individual behavioral extremes (such as fasting and feasting) into a well-middled, individual life fabric; and second, by weaving themselves together with other human and nonhuman agents into a single, well-middled, community life fabric by means of initiating and participating in relationships of mutuality and reciprocity. Humans lived well and lived wisely when they crafted their lives as well-skilled weavers. Editor | Gregg D. Caruso, Corning Community College, SUNY (USA)/Owen Flanagan, Duke University, USA. -

Tlattic in Xochitl in Cuicatl))

A brightness – a signal – a sign (the light explored and questioned everything) ((Tlattic in xochitl in cuicatl)) by Emiliano Rafael Sepulveda B.F.A. Emily Carr University, 2009 Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts in the School for the Contemporary Arts Faculty of Communication, Art and Technology © Emiliano Rafael Sepulveda 2016 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2016 Approval Name: Emiliano Sepulveda Degree: Master of Fine Arts Title: A brightness - a signal - a sign (the light explored and questioned everything) ((tlattic in xochitl in cuicatl)) Examining Committee: Chair: Judy Radul Professor Allyson Clay Senior Supervisor Professor Stephen Collis Supervisor Professor Department of English Elspeth Pratt Supervisor Associate Professor Dana Claxton External Examiner Associate Professor The Department of Art History, Visual Art, and Theory University of British Columbia Date Defended/Approved: September 28, 2016 ii Abstract A brightness – a signal – a sign (the light explored and questioned everything) ((tlattic in xochitl in cuicatl)) is a project that begins with a process of walking throughout Vancouver, finding objects, walking with the objects, then constructing sculptures collaboratively with them. This is done while considering the possibility for quantum entanglement between the human and non-human, and forming a bond between the human body, the sites where the objects are found, and the found objects themselves. This labour is driven by the experience of being an immigrant living within a diaspora and is a performative means for creating a dynamic and reciprocal relationship with the Land of Vancouver. Keywords: Aztlán; sculpture; in xochitl in cuicatl; installation; poetry; diaspora iii Dedication For Gosia and for the person growing within who I've yet to meet Empezamos este viaje juntos - todos juntos seguimos iv Acknowledgements First I want to acknowledge that this work came into being on the traditional unceded territories of the Musqueam, Squamish, and the Tsleil-Waututh Nations. -

PHILOSOPHY – FALL 2019 VARIABLE TITLES and OTHER SPECIAL OFFERINGS See the Catalog/Course Schedule for a Full List

PHILOSOPHY – FALL 2019 VARIABLE TITLES AND OTHER SPECIAL OFFERINGS See the catalog/course schedule for a full list. This flier highlights new courses and courses that are unlikely to be offered again for roughly two years. BRAND NEW THIS TERM (both serve as PHIL electives in any of our programs) • PHIL 126-001: Introduction to Global Philosophies (Ramsey, M/W/F 11:15-12:05) CRN 15207 Philosophy, or the “love of wisdom,” is a human activity found in most, if not all, cultures. This course explores the formative philosophical thought of some of the world’s great cultures so to come to a better understanding of what philosophy is and how philosophy has been done in other cultures and periods. This section examines early Confucianism, early Buddhism, Islamic philosophy and Aztec philosophy, respectively. We will discuss each of the four philosophical traditions on their own terms as well as in terms of the other three. Because we will be juxtaposing these four traditions, students will have an opportunity compare their ways of understanding of concepts like wisdom, good and bad, the human condition, personhood, reality, truth, and knowledge; and hence to deeper their own understanding of these concepts as well. • PHIL 280-001: Philosophy of Science (Brown T/R 11-12:15) CRN 15215 This is an introduction to the philosophy of science focused on questions about its nature, methods and goals. Some of the questions we explore include: What distinguishes science from pseudo-science? What constitutes the ‘scientific method?' and What is scientific objectivity? Students in this course will learn to deploy a variety of philosophical methods to explore both conceptual and practical issues embedded in scientific work. -

The Politics of Decolonial Investigations

THE POLITICS OF DECOLONIAL INVESTIGATIONS WALTER D. MIGNOLO the politics of decolonial investigations ON DECOLONIALITY a series edited by Walter D. Mignolo and Catherine E. Walsh On Decoloniality interconnects a diverse array of perspectives from the lived experiences of coloniality and decolonial thought/praxis in different local histories from across the globe. The series is concerned with colonial- ity’s global logic and scope and with the myriad of decolonial responses and engagements that contest coloniality/modernity’s totalizing violences, claims, and frame, opening toward an otherwise of being, thinking, sensing, knowing, and living; that is, of re-existences and worlds-making. Aimed at a broad audience, from scholars, students, and artists to journalists, activ- ists, and socially engaged intellectuals, On Decoloniality invites a wide range of participants to join one of the fastest-growing debates in the humanities and social sciences that attends to the lived concerns of dignity, life, and the survival of the planet. THE Walter d. mignolo POLITICS OF DECOLONIAL INVESTIGATIONS duke university press durham and london 2021 © 2021 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Aimee C. Harrison Typeset in Portrait Text Regular and itc Avant Garde Gothic by Westchester Publishing Ser vices Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Mignolo, Walter, author. Title: The politics of decolonial investigations / Walter D. Mignolo. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2021. | Series: On decoloniality | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Identifiers: lccn 2020042286 (print) lccn 2020042287 (ebook) isbn 9781478001140 (hardcover) isbn 9781478002574 (ebook) isbn 9781478001492 (paperback) Subjects: lcsh: Decolonization. -

The Nature of Mexica Ethics James Maffie

3 The Nature of Mexica Ethics James Maffie Scholars of Mexica (Aztec) philosophy widely embrace the general claim that (1) reciprocity functions at the heart of Mexica metaphysics' under standing of the nature and continual becoming of the world as well as the role of human beings in contributing to the continual becoming of the world. They also widely embrace several more specific claims: (2) power ful creator beings engender the Fifth Age of the cosmos; (3) these same creator beings engender Fifth Age human beings; (4) they engender human beings by 'deserving' or 'meriting' humans' existence; (5) Fifth Age human beings are tQerefo_ret~ose 'des~rved' 9r 'm_erit~d'int~ ~~\s_tenceby creator beings; (6) Fifth Age human beings are consequently b6rn 'obligated' or 'indebted' to creator beings; and (7) Fifth Age human beings do so by providing f~_r~reator _~eings'co1.1t~,nui,np su~t,en_~p.c~ -~11,d ,e~(/itence. In what follows Ulesl:i out some :of the .more important metaphyskal and meta ethical underpinnings and consequences of these claims, 1 1. Human and Other-Than-Human Reciprocity and Co-Participation in the Fifth Age According to Mexica creation narratives (tlamachiliztlatolzazani/li, liter ally, 'wisdom tellings' [Bierhorst 1992, vii]), the history of the cosmos consists of a series of five Ages or Suns. The succession of the first four Ages consists of the creator beings, Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca, tak ing turns creating their own and destroying the other's Age. Each of the four Ages is populated by its own particular kind of human being who is also destroyed. -

In Huehue Tlamanitiliztli and La Verdad: Nahua and European Philosophies in Fray Bernardino De Sahagúnʼs Colloquios Y Doctrina Cristiana by James Maffie

In Huehue Tlamanitiliztli and la Verdad: Nahua and European Philosophies in Fray Bernardino de Sahagúnʼs Colloquios y doctrina cristiana by James Maffie In Huehue Tlamanitiliztli and la Verdad: Nahua and European Philosophies in Fray Bernardino de Sahagún’s Colloquios y doctrina cristiana by James Maffie English Abstract Bernardino de Sahagún’s Colloquios y doctrina cristiana reproduces an exchange that occurred in 1524 between the first twelve Franciscans sent to the New World and a group of Nahua elite. I argue the Colloquois contains no syllogistic debate and little genuine dialogue. Nahuas and Franciscans talk past one another in a case of what James Lockhart calls “double mistaken identity.” Nahuas and Franciscans address one another from two, alternative philosophical orientations: what I call “path-oriented” and “truth-oriented” (respectively). These consist of two constellations of alternatively defined notions of wisdom, knowledge, reasoning, belief, language, morality, religion, and in the end, how to live. Truth-oriented philosophies define these notions in terms of truth. Path-oriented philosophies define these notions in terms of finding, making, and extending a lifeway. Resumen en español El texto Colloquios y doctrina cristiana de Bernardino de Sahagún reproduce un intercambio que ocurre en el año 1524 entre los primeros doce franciscanos enviados al Nuevo Mundo y un grupo de élites Nahua. Propongo que Colloquios no contiene debate silogístico e incluye poco diálogo genuino. Los Nahua y los franciscanos hablan sin realmente comunicarse en un caso de lo que James Lockhart llama una “doble identidad equivocada” (double mistaken identity). Los Nahua y los franciscanos se dirigen los unos a los otros desde dos orientaciones filosóficas alternativas: las cuales yo llamo, respectivamente, las filosofías “orientadas por senderos” (path-oriented) y las que son “orientadas por la verdad” (truth-oriented). -

Aztec Philosophy: Understanding a World in Motion

Aztec (Mexica) Philosophy Instructor: Jim Maffie Office: Key 2139 Office Hrs: MW 12:00-1:00 or by appointment E-mail: [email protected] Phone: 301-405-8961 Course Description: The course consists of two parts. The first pursues an in-depth examination of the philosophico-religious worldview and concepts of the conquest-era Mexica (Aztecs) with special attention to their metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, aesthetics, and understanding of human sacrifice. The second examines European debates concerning the moral justification and legitimacy of Europeans’ conquest and domination of the native peoples of the “New World.” Course Requirements and Grading*: Students are required to attend lectures, participate in discussions, and complete three take-home exams each of which counts 25% of the final grade. Class participation counts for 25%. Late papers will be penalized one-half letter grade per academic day (not per class period). Electronic submissions will not be accepted. 75%: Three 3-5 page essay take-home exams (25% each) 25%: Class participation (assessed along with each of the three exams) Students are expected to demonstrate in their essays: (a) the ability to convey a theme or argument clearly and coherently; (b) the ability to analyze critically and to synthesize the work of others; (c) the ability to acquire and apply information from appropriate sources, and reference sources appropriately; and (d) their competence in standard written English. Learning assessment Outcome The course asks that students participate in class discussions and complete three essay take-home exams. Both exercises provide students with the opportunity to understand a philosophic-religious viewpoint alien to their own as well as compare and contrast the philosophico-religious concepts and categories (e.g. -

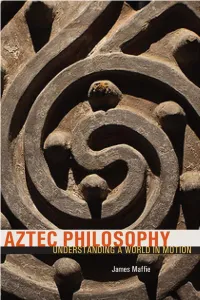

Aztec Philosophy: Understanding a World in Motion / James Maffie

Aztec Philosophy Aztec Philosophy Understanding a World in Motion James Maffie UNIVERSITY PRESS OF COLORADO Boulder © 2014 by University Press of Colorado Published by University Press of Colorado 5589 Arapahoe Avenue, Suite 206C Boulder, Colorado 80303 All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of the Association of American University Presses. The University Press of Colorado is a cooperative publishing enterprise supported, in part, by Adams State University, Colorado State University, Fort Lewis College, Metropolitan State University of Denver, Regis University, University of Colorado, University of Northern Colorado, Utah State University, and Western State Colorado University. ∞ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences – Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48-1992 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Maffie, James. Aztec philosophy: understanding a world in motion / James Maffie. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-60732-222-1 (cloth: alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-60732-223-8 (ebook) 1. Aztec philosophy. 2. Aztecs—Folklore. I. Title. F1219.76.P55M35 2013 199’.7208997452—dc23 2013018407 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Cover photo credit: Almena en forma de caracol cortado, El Museo del Templo Mayor, Mexico City, Mexico. Photograph by Jorge Pérez de Lara Elías. To my mother, Elaine Wack Maffie, and the memory of my father, Cornelius Michael Maffie. Contents Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 Chapter 1. Teotl 21 1.1.