Danila Zuljan Kumar Slovenian in the Autonomous Region of Friuli

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SEMANTIC DEMARCATION of the CONCEPTS of ENDONYM and EXONYM PRISPEVEK K POMENSKI RAZMEJITVI TERMINOV ENDONIM in EKSONIM Drago Kladnik

Acta geographica Slovenica, 49-2, 2009, 393–428 SEMANTIC DEMARCATION OF THE CONCEPTS OF ENDONYM AND EXONYM PRISPEVEK K POMENSKI RAZMEJITVI TERMINOV ENDONIM IN EKSONIM Drago Kladnik BLA@ KOMAC Bovec – Flitsch – Plezzo je mesto na zahodu Slovenije. Bovec – Flitsch – Plezzo is a town in western Slovenia. Drago Kladnik, Semantic Demarcation of the Concepts of Endonym and Exonym Semantic Demarcation of the Concepts of Endonym and Exonym DOI: 10.3986/AGS49206 UDC: 81'373.21 COBISS: 1.01 ABSTRACT: This article discusses the delicate relationships when demarcating the concepts of endonym and exonym. In addition to problems connected with the study of transnational names (i.e., names of geographical features extending across the territory of several countries), there are also problems in eth- nically mixed areas. These are examined in greater detail in the case of place names in Slovenia and neighboring countries. On the one hand, this raises the question of the nature of endonyms on the territory of Slovenia in the languages of officially recognized minorities and their respective linguistic communities, and their relationship to exonyms in the languages of neighboring countries. On the other hand, it also raises the issue of Slovenian exonyms for place names in neighboring countries and their relationship to the nature of Slovenian endonyms on their territories. At a certain point, these dimensions intertwine, and it is there that the demarcation between the concepts of endonym and exonym is most difficult and problematic. KEY WORDS: geography, geographical names, endonym, exonym, exonimization, geography, linguistics, terminology, ethnically mixed areas, Slovenia The article was submitted for publication on May 4, 2009. -

Emerald Cycling Trails

CYCLING GUIDE Austria Italia Slovenia W M W O W .C . A BI RI Emerald KE-ALPEAD Cycling Trails GUIDE CYCLING GUIDE CYCLING GUIDE 3 Content Emerald Cycling Trails Circular cycling route Only few cycling destinations provide I. 1 Tolmin–Nova Gorica 4 such a diverse landscape on such a small area. Combined with the turbulent history I. 2 Gorizia–Cividale del Friuli 6 and hospitality of the local population, I. 3 Cividale del Friuli–Tolmin 8 this destination provides ideal conditions for wonderful cycling holidays. Travelling by bicycle gives you a chance to experi- Connecting tours ence different landscapes every day since II. 1 Kolovrat 10 you may start your tour in the very heart II. 2 Dobrovo–Castelmonte 11 of the Julian Alps and end it by the Adriatic Sea. Alpine region with steep mountains, deep valleys and wonderful emerald rivers like the emerald II. 3 Around Kanin 12 beauty Soča (Isonzo), mountain ridges and western slopes which slowly II. 4 Breginjski kot 14 descend into the lowland of the Natisone (Nadiža) Valleys on one side, II. 5 Čepovan valley & Trnovo forest 15 and the numerous plateaus with splendid views or vineyards of Brda, Collio and the Colli Orientali del Friuli region on the other. Cycling tours Familiarization tours are routed across the Slovenian and Italian territory and allow cyclists to III. 1 Tribil Superiore in Natisone valleys 16 try and compare typical Slovenian and Italian dishes and wines in the same day, or to visit wonderful historical cities like Cividale del Friuli which III. 2 Bovec 17 was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage list. -

Danila Zuljan Kumar 1. the Ter/Torre Valley Dialect of Slovenian in The

EUROPA ORIENTALIS 35 (2016) THE INFLUENCE OF ITALIAN AND FRIULIAN ON THE CLAUSAL CONSTRUCTIONS OF THE TER/TORRE VALLEY DIALECT OF SLOVENIAN Danila Zuljan Kumar 1. The Ter/Torre Valley dialect of Slovenian in the frame of the Slovenian dialects The Ter/Torre Valley dialect is a Slovenian dialect spoken in Friuli Venezia Giulia and in some villages of the so called Breginjski kot in western Slove- nia. According to the diachronic division of the Slovenian dialects based on the older linguistic phenomena, i.e. development of OCSln.*/*ō, OCSln. */*-, denasalization of Proto-Slavic nasal vowels *ę/*ǫ and lengthening of OCSln. short acuted vowels in a non-final syllable the dialect belongs to the north-western dialectal basis with diphthongization of OCSln.*/*ō > ie/uo (Tr.V.d. snìeːx ‘snow’, Tr.V.d nùọjć ‘night’), OCSln. */*- > aː (Tr.V.d. àːs ‘village’, Tr.V.d páːsjə ‘dog’s), late denasalization of *ę/*ǫ (Tr.V.d. léːdatə ‘to watch’, Tr.V.d. móːka ‘flour’) and early lengthening of OCSln. short acu- ted vowels in a non-final syllable and consequently merger of OCSln. * and *- (Tr.V.d. zvíːezda ‘star’, Tr.V.d. bríːeza ‘birch’). According to the synchronic division of the Slovenian dialects based on the younger linguistic phenomena, like the presence of inhereted tonal oppo- sitions, the absence of accent retraction of the type OCSln.*sestr, *koz and *məgl > sèstra, kòza, mgla (Tr.V.d. sestra ‘sister’, koza ‘goat’, mala ‘fog’), OCSln.*-m > -n (Tr.V.d. son < səm ‘I am’) and language borrowing at all le- vels of language (phonology, morphology, syntax and lexicon), the dialect be- longs together with the Nadiško/Natisone Valley dialect, Obsoško/Soča and Brda dialects to the Venetian Slovenian sub-group of the Slovenian Littoral 1 dialect group. -

From the Alps to the Adriatic

EN From the Alps to the Adriatic Sea - a century after the Isonzo Front Soča, do tell “Alone alone alone I have to be in eternity self and self in eternity discover my lumnious feathers into afar space release and peace from beyond land in self grip.” Srečko Kosovel Dear travellers Have you ever embraced the Alps and the Adriatic with by the Walk of Peace from the Alps to the Adriatic Sea that a single view? Have you ever strolled along the emerald runs across green and diverse landscape – past picturesque Soča River from its lively source in Triglav National Park towns, out-of-the-way villages and open fireplaces where to its indolent mouth in the nature reserve in the Bay of good stories abound. Trieste? Experience the bonds that link Italy and Slove- nia on the Walk of Peace. Spend a weekend with a knowledgeable guide, by yourself or in a group and see the sites by car, on foot or by bicycle. This is where the Great War cut fiercely into serenity a century Tourism experience providers have come together in the T- ago. Upon the centenary of the Isonzo Front, we remember lab cross-border network and together created new ideas for the hundreds of thousands of men and boys in the trenches your short break, all of which can be found in the brochure and on ramparts that they built with their own hands. Did entitled Soča, Do Tell. you know that their courageous wives who worked in the rear sometimes packed clothing in the large grenades instead of Welcome to the Walk of Peace! Feel the boundless experi- explosives as a way of resistance? ences and freedom, spread your wings among the vistas of the mountains and the sea, let yourself be pampered by the Today, the historic heritage of European importance is linked hospitality of the locals. -

United Nations ECE/MP.WAT/2015/10

United Nations ECE/MP.WAT/2015/10 Economic and Social Council Distr.: General 13 November 2015 English only Economic Commission for Europe Meeting of the Parties to the Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes Seventh session Budapest, 17–19 November 2015 Item 4(i) of the provisional agenda Draft assessment of the water-food-energy-ecosystems nexus in the Isonzo/Soča River Basin Assessment of the water-food-energy-ecosystems nexus in the Isonzo/Soča River Basin* Prepared by the secretariat with the Royal Institute of Technology Summary At its sixth session (Rome, 28–30 November 2012), the Meeting of the Parties to the Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes requested the Task Force on the Water-Food-Energy-Ecosystems Nexus, in cooperation with the Working Group on Integrated Water Resources Management, to prepare a thematic assessment focusing on the water-food-energy-ecosystems nexus for the seventh session of the Meeting of the Parties (see ECE/MP.WAT/37, para. 38 (i)). The present document contains the scoping-level nexus assessment of the Isonzo/Soča River Basin with a focus on the downstream part of the basin. The document is the result of an assessment process carried out according to the methodology described in publication ECE/MP.WAT/46, developed on the basis of a desk study of relevant documentation, an assessment workshop (Gorizia, Italy; 26-27 May 2015), as well as inputs from local experts and officials of Italy. Updates in the process were reported at the meetings of the Task Force. -

Thomas RAINER, Reinhard F. SACHSENHOFER, Gerd RANTITSCH, Uroš HERLEC & Marko VRABEC

Austrian Journal of Earth Sciences Volume 102/2 Vienna 2009 Organic maturity trends across the Variscan discordance in the Alpine-Dinaric Transition Zone (Slovenia, Austria, Italy): Variscan versus Alpidic thermal overprint_________ Thomas RAINER1)3)*), Reinhard F. SACHSENHOFER1), Gerd RANTITSCH1), Uroš HERLEC2) & Marko VRABEC2) 1) KEYWORDS Mining University Leoben, Department for Applied Geosciences and Geophysics, 8700 Leoben, Austria; 2) University of Ljubljana, Faculty of Natural Sciences and Engineering, Department of Geology, Vitrinite reflectance Variscan Discordance 2) Aškerčeva 12, 1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia; Northern Dinarides 3) Present Address: OMV Exploration & Production GmbH, Trabrennstrasse 6-8, 1020 Wien, Austria; Southern Alps Carboniferous *) Corresponding author, [email protected] Eastern Alps Abstract In the Southern Alps and the northern Dinarides the main Variscan deformation event occurred during Late Carboniferous (Bashki- rian to Moscovian) time. It is represented locally by an angular unconformitiy, the “Variscan discordance”, separating the pre-Variscan basement from the post-Variscan (Moscovian to Cenozoic) sedimentary cover. The main aim of the present contribution is to inves- tigate whether a Variscan thermal overprint can be detected and distinguished from an Alpine thermal overprint due to Permo-Meso- zoic basin subsidence in the Alpine-Dinaric Transition Zone in Slovenia. Vitrinite reflectance (VR) is used as a temperature sensitive parameter to determine the thermal overprint of pre- and post-Variscan sedimentary successions in the eastern part of the Southern Alps (Carnic Alps, South Karawanken Range, Paški Kozjak, Konjiška Gora) and in the northern Dinarides (Sava Folds, Trnovo Nappe). Neither in the eastern part of the Southern Alps, nor in the northern Dinarides a break in coalification can be recognized across the “Variscan discordance”. -

Attitudes Towards the Safeguarding of Minority Languages and Dialects in Modern Italy

ATTITUDES TOWARDS THE SAFEGUARDING OF MINORITY LANGUAGES AND DIALECTS IN MODERN ITALY: The Cases of Sardinia and Sicily Maria Chiara La Sala Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Department of Italian September 2004 This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. ABSTRACT The aim of this thesis is to assess attitudes of speakers towards their local or regional variety. Research in the field of sociolinguistics has shown that factors such as gender, age, place of residence, and social status affect linguistic behaviour and perception of local and regional varieties. This thesis consists of three main parts. In the first part the concept of language, minority language, and dialect is discussed; in the second part the official position towards local or regional varieties in Europe and in Italy is considered; in the third part attitudes of speakers towards actions aimed at safeguarding their local or regional varieties are analyzed. The conclusion offers a comparison of the results of the surveys and a discussion on how things may develop in the future. This thesis is carried out within the framework of the discipline of sociolinguistics. ii DEDICATION Ai miei figli Youcef e Amil che mi hanno distolto -

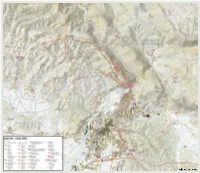

Sabotin-Zemljevid.Pdf

S – P P – S dalle Alpi all`Adriatico Alpi dalle Sabotin – Park miru Sabotin – the Park of Peace Sabotin – Der Friedenspark Sabotin – il Parco della pace S I von den Alpen bis zur Adria zur bis Alpen den von F W from the Alps to the Adriatic the to Alps the from Sabotin je zaradi svoje lege odlična razgledna točka za širše območje Go- Due to its position Mt. Sabotin is a splendid vantage point for the wider Sabotin ist wegen seiner Lage ein ausgezeichneter Aussichtspunkt für Il monte Sabotin (Sabotino) è, grazie alla sua posizione, un’eccellente P W T od Alp do Jadrana do Alp od riške in nudi pogled na Sveto Goro, Škabrijel, Vipavsko dolino, Furlan- area of the Goriška region and offers a view over the hills of Sveta Gora das breitere Gebiet der Goriška Region und bietet die Aussicht auf punto panoramico per il più ampio territorio goriziano, offrendo una P sko nižino, Goriška Brda in Julijske Alpe. Zaradi burne zgodovine in na- and Škabrijel, the Vipava valley, the Friuli lowlands, the Goriška Brda Sveta Gora, Škabrijel, Vipavatal, Friauler Ebene, Weinbau- und Obst- visuale sul Sveta Gora (Monte Santo), Škabrijel (San Gabriele), la valle ravoslovnih znamenitosti je pomembna izletniška točka, ki jo je vredno area and the Julian Alps. Because of its turbulent history and natural baugebiet Goriška Brda und Julische Alpen. Wegen seiner wechselvollen della Vipava, la pianura friulana, Goriška Brda (il Collio) e le Alpi Giu- T K K T ¶ T ¶ obiskati. Pohodnikom in kolesarjem je dostopen tudi pozimi, ko vrhove peculiarities it is an important tourist destination worth visiting. -

The Sound Patterns of Camuno: Description and Explanation in Evolutionary Phonology

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2014 The Sound Patterns Of Camuno: Description And Explanation In Evolutionary Phonology Michela Cresci Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/191 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE SOUND PATTERNS OF CAMUNO: DESCRIPTION AND EXPLANATION IN EVOLUTIONARY PHONOLOGY by MICHELA CRESCI A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Linguistics in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City Universtiy of New York 2014 i 2014 MICHELA CRESCI All rights reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Linguistics in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. JULIETTE BLEVINS ____________________ __________________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee GITA MARTOHARDJONO ____________________ ___________________________________ Date Executive Officer KATHLEEN CURRIE HALL DOUGLAS H. WHALEN GIOVANNI BONFADINI Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract THE SOUND PATTERNS OF CAMUNO: DESCRIPTION AND EXPLANATION IN EVOLUTIONARY PHONOLOGY By Michela Cresci Advisor: Professor Juliette Blevins This dissertation presents a linguistic study of the sound patterns of Camuno framed within Evolutionary Phonology (Blevins, 2004, 2006, to appear). Camuno is a variety of Eastern Lombard, a Romance language of northern Italy, spoken in Valcamonica. Camuno is not a local variety of Italian, but a sister of Italian, a local divergent development of the Latin originally spoken in Italy (Maiden & Perry, 1997, p. -

Alla Scoperta Degli Itinerari “Sentiero Smeraldo” Promossiartment Dal Gruppo Hit in Collaborazione Con L’Ente Del Turismo Sloveno

HIT hoteli, igralnice, turizem d.d. Nova Gorica Delpinova 7a 5000 Nova Gorica wd_Picture Slovenija t +386 5 336 40 00 f +386 5 302 64 30 [email protected]; www.hit.si wd_Picture wd_ID Comunicazioni aziendali t +386 5 336 42 15 f +386 5 302 55 57 [email protected] Delpinova 7a wd_DocIDwd_Do 5000 Nova Gorica Gruppo Hit_Itinerari Sentiero Smeraldo cID Slovenija wd_Departmentwd_Departmentwd_Departme ntwd_Departmentwd_Departmentwd_Departm wd_Zadeva entwd_Departmentwd_Departmentwd_Depart mentwd_Departmentwd_Departmentwd_Depa rtmentwd_Departmentwd_Departmentwd_Dep Alla scoperta degli itinerari “Sentiero Smeraldo” promossiartment dal Gruppo Hit in collaborazione con L’Ente del Turismo sloveno. Immense distese verdi, paesaggi carsici, fortezze arroccate su imponenti colline, parchi nazionali, monti maestosi, piccoli paesi montani e palazzi d’epoca; queste tra le principali meraviglie che sorgono lungo il percorso del fiume più bello d’Europa, il Soča (l’Isonzo). Il suo colore verde smeraldo regala il nome alla selezione di quattro itinerari che il Gruppo Hit, principale corporate multinazionale turistica slovena, propone con la collaborazione dell’Ente Turismo sloveno per promuovere il patrimonio turistico locale sia nella stagione invernale che in quella estiva. I percorsi turistici vedono Nova Gorica (in foto) come punto di partenza per proseguire alla scoperta delle bellezze naturalistiche che caratterizzano la Sloveniaed in particolare la Valle del fiume Vipava (Vipacco), del fiume Soča (Isonzo), il Brda (Collio Sloveno)e il Kras (Carso sloveno). La cittadina, fondata dopo la seconda guerra mondiale,è unita con la città italiana di Gorizia (come testimonia il mosaico della piazza Transalpina che si divide tra i due Stati) e accoglie le principali strutture ricettive che il Gruppo Hit ha predisposto per il soggiorno. -

HIKING in SLOVENIA Green

HIKING IN SLOVENIA Green. Active. Healthy. www.slovenia.info #ifeelsLOVEnia www.hiking-biking-slovenia.com |1 THE LOVE OF WALKING AT YOUR FINGERTIPS The green heart of Europe is home to active peop- le. Slovenia is a story of love, a love of being active in nature, which is almost second nature to Slovenians. In every large town or village, you can enjoy a view of green hills or Alpine peaks, and almost every Slove- nian loves to put on their hiking boots and yell out a hurrah in the embrace of the mountains. Thenew guidebook will show you the most beauti- ful hiking trails around Slovenia and tips on how to prepare for hiking, what to experience and taste, where to spend the night, and how to treat yourself after a long day of hiking. Save the dates of the biggest hiking celebrations in Slovenia – the Slovenia Hiking Festivals. Indeed, Slovenians walk always and everywhere. We are proud to celebrate 120 years of the Alpine Associati- on of Slovenia, the biggest volunteer organisation in Slovenia, responsible for maintaining mountain trails. Themountaineering culture and excitement about the beauty of Slovenia’s nature connects all generations, all Slovenian tourist farms and wine cellars. Experience this joy and connection between people in motion. This is the beginning of themighty Alpine mountain chain, where the mysterious Dinaric Alps reach their heights, and where karst caves dominate the subterranean world. There arerolling, wine-pro- ducing hills wherever you look, the Pannonian Plain spreads out like a carpet, and one can always sense the aroma of the salty Adriatic Sea. -

HISTORY of the 87Th MOUNTAIN INFANTRY in ITALY

HISTORY of the 87th MOUNTAIN INFANTRY in ITALY George F. Earle Captain, 87th Mountain Infantry 1945 HISTORY of the 87th MOUNTAIN INFANTRY in ITALY 3 JANUARY 1945 — 14 AUGUST 1945 Digitized and edited by Barbara Imbrie, 2004 CONTENTS PREFACE: THE 87TH REGIMENT FROM DECEMBER 1941 TO JANUARY 1945....................i - iii INTRODUCTION TO ITALY .....................................................................................................................1 (4 Jan — 16 Feb) BELVEDERE OFFENSIVE.........................................................................................................................10 (16 Feb — 28 Feb) MARCH OFFENSIVE AND CONSOLIDATION ..................................................................................24 (3 Mar — 31 Mar) SPRING OFFENSIVE TO PO VALLEY...................................................................................................43 (1 Apr — 20 Apr) Preparation: 1 Apr—13 Apr 43 First day: 14 April 48 Second day: 15 April 61 Third day: 16 April 75 Fourth day: 17 April 86 Fifth day: 18 April 96 Sixth day: 19 April 99 Seventh day: 20 April 113 PO VALLEY TO LAKE GARDA ............................................................................................................120 (21 Apr — 2 May) Eighth day: 21 April 120 Ninth day: 22 April 130 Tenth day: 23 April 132 Eleventh and Twelfth days: 24-25 April 149 Thirteenth day: 26 April 150 Fourteenth day: 27 April 152 Fifteenth day: 28 April 155 Sixteenth day: 29 April 157 End of the Campaign: 30 April-2 May 161 OCCUPATION DUTY AND