EDWARD HOPPER's BLACK SUN Arthur Kroker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hopperville Express

Curriculum Units by Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute 1989 Volume V: America as Myth The HopperVille Express Curriculum Unit 89.05.01 by Casey Cassidy This curriculum unit is designed to utilize Edward Hopper’s realistic 20th century paintings as a “vehicle” to transport middle school children from the hills and seasides of New England, through the metropolis of New York City, and across the plains of the western United States. As our unit continues along its journey, it will cross a timeline of approximately forty years which will serve to highlight technological improvements in transportation, changes in period attire, and various architectural styles. We will experience a sense of nostalgia as we view a growing spirit of nationalistic pride as we watch America grow, change, and move forward through the eyes of Edward Hopper. The strategies in this unit will encourage the youngsters to use various skills for learning. Each student will have the opportunity to read, to critically examine slides and lithographs of selected Hopper creations, to fully participate in teacherled discussions of these works of art, and to participate first hand as a commercial artist—i.e. they will be afforded an opportunity to go out into their community, traveling on foot or by car (as Edward Hopper did on countless occasions), to photograph or to sketch buildings, scenes, or structures similar to commonplace areas that Hopper painted himself. In this way, we hope to create a sense of the challenge facing every artist as they themselves seek to create their own masterpieces. Hopper was able “to portray the commonplace and make the ordinary poetic.”1 We hope our students will be able to understand these skills and to become familiar with the decisions, the inconveniences, and the obstacles of every artist as they ply their trade. -

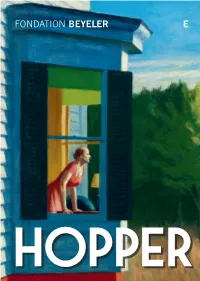

Room Guide Edward Hopper

FONDATION BEYELER E EDWARD HOPPER INTRODUCTION 26 January – 17 May 2020 Edward Hopper (1882–1967) is one of the great familiar yet ultimately little known exponents of modern art. Some of his works have become exceptionally popular and belong to the cultural memory of our age. Yet some aspects of his work are known only to a few specialists. Many of his paintings, as well as his watercolors and drawings, thus remain to be discovered. Our exhibition makes an important contribution in this respect. For the first time, it brings together Hopper’s landscapes, including urban landscapes, providing visitors with deep insights into the artist’s external and internal worlds. Renowned filmmaker Wim Wenders, a long-time, self-avowed Hopper fan, has created a personal tribute to Cover: Edward Hopper the artist, the 3D film Two or Three Things I Know about Cape Cod Morning, 1950 (detail) Edward Hopper, specially for the exhibition at the Oil on canvas, 86.7 x 102.3 cm Smithsonian American Art Museum Fondation Beyeler. Starting with motifs from Hopper’s © Heirs of Josephine Hopper / 2020 ProLitteris, Zurich. pictures, he revives the artist’s characteristic melancholy Photo: Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gene Young mood. The film is screened in the last room of the exhibition. We hope you enjoy the exhibition and would be delighted for you to share your experience with others. ROOM 1 ROOM 2 1 2 Railroad Sunset, 1929 Square Rock, Ogunquit, 1914 Railroad Sunset shows the passage from day into night, Like Edward Hopper’s other landscape paintings, this an evening sky displaying striking light and color mood. -

Edward Hopper's Adaptation of the American Sublime

Rhetoric and Redress: Edward Hopper‘s Adaptation of the American Sublime A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Fine Arts Rachael M. Crouch August 2007 This thesis titled Rhetoric and Redress: Edward Hopper’s Adaptation of the American Sublime by RACHAEL M. CROUCH has been approved for the School of Art and the College of Fine Arts by Jeannette Klein Assistant Professor of Art History Charles A. McWeeny Dean, College of Fine Arts Abstract CROUCH, RACHAEL M., M.F.A., August 2007, Art History Rhetoric and Redress: Hopper’s Adaptation of the American Sublime (80 pp.) Director of Thesis: Jeannette Klein The primary objective of this thesis is to introduce a new form of visual rhetoric called the “urban sublime.” The author identifies certain elements in the work of Edward Hopper that suggest a connection to earlier American landscape paintings, the pictorial conventions of which locate them within the discursive formation of the American Sublime. Further, the widespread and persistent recognition of Hopper’s images as unmistakably American, links them to the earlier landscapes on the basis of national identity construction. The thesis is comprised of four parts: First, the definitional and methodological assumptions of visual rhetoric will be addressed; part two includes an extensive discussion of the sublime and its discursive appropriation. Part three focuses on the American Sublime and its formative role in the construction of -

Alienation in Edward Hopper's and Jackson Pollock's

ALIENATION IN EDWARD HOPPER’S AND JACKSON POLLOCK’S PAINTINGS: A COMPARISON AND CONTRAST A Thesis by Zohreh Dalirian Bachelor of Fine Arts, Shahed University, 2005 Submitted to the Department of Liberal Arts and Sciences and the faculty of the Graduate School of Wichita State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts May 2010 © Copyright 2010 by Zohreh Dalirian All Rights Reserved ALIENATION IN EDWARD HOPPER’S AND JACKSON POLLOCK’S PAINTINGS: A COMPARISON AND CONTRAST The following faculty members have examined the final copy of this thesis for form and content, and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts with a major in Liberal Studies. _________________________________ Dorothy Billings, Committee Chair _________________________________ David Soles, Committee Member __________________________________ Mary Sue Foster, Committee Member iii DEDICATION To my lovely mother, my dear husband, and the memory of my father. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to extend my gratitude to committee chair, Dr. Dorothy Billings, for encouraging me to develop my ideas, and my advisor, Dr. Soles, who supported me during my degree program, and also Professor Foster for serving on my thesis committee and for her valuable comments. I am very grateful to my father, who passed away a few days before my thesis defense, and my mother and my sisters for their impeccable help and support. Finally, I would like to express my exclusive appreciation to my beloved husband, Ruhola, who supported me from the beginning to the very end. v ABSTRACT In this thesis I study alienation in Edward Hopper’s and Jackson Pollack’s paintings. -

The Mind in Motion: Hopper's Women Through Sartre's Existential Freedom

Intercultural Communication Studies XXIV(1) 2015 WANG The Mind in Motion: Hopper’s Women through Sartre’s Existential Freedom Zhenping WANG University of Louisville, USA Abstract: This is a study of the cross-cultural influence of Jean-Paul Sartre on American painter Edward Hopper through an analysis of his women in solitude in his oil paintings, particularly the analysis of the mind in motion of these figures. Jean-Paul Sartre was a twentieth century French existentialist philosopher whose theory of existential freedom is regarded as a positive thought that provides human beings infinite possibilities to hope and to create. His philosophy to search for inner freedom of an individual was delivered to the US mainly through his three lecture visits to New York and other major cities and the translation by Hazel E. Barnes of his Being and Nothingness. Hopper is one of the finest painters of the twentieth-century America. He is a native New Yorker and an artist who is searching for himself through his painting. Hopper’s women figures are usually seated, standing, leaning forward toward the window, and all are looking deep out the window and deep into the sunlight. These women are in their introspection and solitude. These figures are usually posited alone, but they are not depicted as lonely. Being in outward solitude, they are allowed to enjoy the inward freedom to desire, to imagine, and to act. The dreaming, imagining, expecting are indications of women’s desires, which display their interior possibility or individual agency. This paper is an attempt to apply Sartre’s philosophy to see that these women’s individual agency determines their own identity, indicating the mind in motion. -

Reasons for Moving: Mark Strand on the Art of Edward Hopper1

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Viagens pela Palavra. provided by Repositório Aberto da Universidade Aberta 129 Reasons for Moving: Mark Strand on the Art of Edward Hopper1 Jeffrey Scott Childs Universidade Aberta Edward Hopper’s work has repeatedly been regarded by a range of critics as among the most significant productions of 20th century American art and has been discussed in connection with phenomena as diverse as French symbolism (both in poetry and painting), the work of Piet Mondrian and of the so-called ash can school, as well as viewed as a forerunner of both pop art and abstract expressionism. A recent exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art included several of Hopper’s paintings under the rubric of “Figurative Expressionism.”1 If this description is less than helpful in critically locating Hopper’s work, I hope it will suggest some of the complexities inherent in coming to terms with his art and encourage viewers to look at it from a variety of different perspectives, which, as I hope to show, is one of Hopper’s most significant projects. Mark Strand is the author of numerous works dating from his first volume of poetry, Sleeping with One Eye Open, published in 1964, to his most recent, Chicken, Shadow, Moon & More, published in 2000. Among these are translations of the poets Raphael Alberti and Carlos Drummond de Andrade, as well as books on painters, such as William Bailey, and painting (which he studied under Josef Albers at the Yale Art School from 1956 to 1959). -

American Realism: an Independence of Style the Ashcan School

AMERICAN REALISM: AN INDEPENDENCE OF STYLE THE ASHCAN SCHOOL Lecture 2 – The Spaces Between Us: The Art of Edward Hopper JAMES HILL – 4 MAY, 2021 READING LIST Michael Lewis American Art and Architecture, 2006, Thames & Hudson. Edward Lucie Smith American Realism, 1994, Thames & Hudson. Robert A Slaton Beauty in the City - The Ashcan School, 2017, Excelsior Editions. Colin Bailey et al The World of William Glackens - The C. Richard Art Lectures, 2011, Sansom Foundation/ Art Publishers. Gail Levin Edward Hopper – The Art and the Artist, 1981 – Whitney Museum of American Art/Norton Whitney. Rolf G Renner. Hopper, 2015 – Taschen. Judith A Barter et al America after the Fall - Painting in the 1930s, 2017, The Art Institute of Chicago/Yale University Press. SLIDE LIST Edward Hopper, Self Portrait, 1925, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York Edward Hopper, Caricature of Hopper as a Boy with Books on Freud and Jung, 1925-35, Private Collection. Edward Hopper, Night Shadows, 1928, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York Edward Hopper, Evening Wind, 1921, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York Edward Hopper, Summer Interior, 1909, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York Robert Henri, Blackwell’s Island, 1900, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York Edward Hopper, Blackwell’s Island, 1911, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York Edward Hopper, Louvre in a Thunderstorm, 1909, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York Edward Hopper, Soir Bleu, 1914, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York John Sloan, Hairdresser’s Window, 1907, Wadsworth -

Edward Hopper a Catalogue Raisonne

Edward Hopper A Catalogue Raisonne Volume III Oils Gail Levin Whitney Museum of American Art, New York in associalion wilh W. W. Norton & Company, New York • London American Village, 1912 (0-183) City, The, ig27 (0-252) Index of Titles Apartment Houses, 1923 (0-242) City Hoofs, ig32 (0-288) [Apartment Houses, Harlem River], City Sunlight, 1954 (0-550) Oils c. 1930(0-275) [Clamdigger], 1^55(0-297) Approaching a City, 1946 (0-332) Coast Guard Station, 1929(0-267) Apres midi de Juin or L'apres midi de [Cobb's Barns und Distant Houses], 1930-35 Prinletnps, 1907 (0-143) (0-278) [Artist's Bedroom, NyackJ, c. 1905-06 [Cobb's Barns, South Truro], 1950-55 (0-122) (0-279) [Artist's Bedroom, Nyack, The], c. 1905- Compartment C, Car 293, 1938 (0-506) 06 (0-121) Conference at Night, ig4g (0-338) [Artist Sealed at Easel]', igo3~o6 (0-84) [Copy after Edouard Manet's Woman with August in the City, 1945 (0-329) a Parrot], c. 1902-03 (0-19) Automat, 1927 (0-251) CornBeltCity 1947 (0-554) Corn Hill, Truro, 1930 (0-272) [Back of Seated Male Nude Model], [Cottage and Fence], c. igo4-o6 (0-97) c. 1902-04 (0-28) [Cottage in Foliage], c. 1 go4-o6 (0-98) Barber Shop, 1931 (0-285) /Country Road], c. 1897 (0-4) /Bedroom], c. 1905-06 (0-124) Cove at Ogunquit, 1914 (0-193) Berge, La (0-171) Bistro, Le or The Wine Shop, 1909 (0-174) Dauphinee House, 1952 (0-286) [Blackhead, Monhegan], 1916-19 (0-220) Dawn Before Gettysburg, 1954 (0-295) [Blackhead, Monhegan], 1916-19 (0-221) Dawn in Pennsylvania, ig42 (0-323) [Blackhead, Monhegan], 1916-19 (0-222) [Don Quixote on Horseback], c. -

Edward Hopper’S (1882–1967) Most Admired Paint- Ings Are Night Scenes

any of Edward Hopper’s (1882–1967) most admired paint- ings are night scenes. An enthusiast of both movies and Mthe theater, he adapted the device of highlighting a scene against a dark background, providing the viewer with a sense of sit- ting in a darkened theater waiting for the drama to unfold. By staging his pictures in darkness, Hopper was able to illuminate the most important features while obscuring extraneous detail. The set- tings in Night Windows, Room in New York, Nighthawks, and other night compositions enhance the emotional content of the works — adding poignancy and suggestions of danger or uneasiness. EDWARD HOPPER by janet l. comey hours of darkness The Nyack, New York, born Hopper trained as an illustrator before transferring to the New York School of Art, where he studied under Ashcan School painter Robert Henri (1869–1929). Near the beginning of his career, he revealed an interest in night scenes. On his first trip to Europe in 1906–07, he was fascinated by Rembrandt’s Night Watch (1642) in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam; writing to his mother that the painting was “the most wonderful thing of [Rembrandt’s] I have seen, it’s past belief in its reality — it almost amounts to deception.” In several early paintings, Hopper depicted rooms and figures in moonlight. Thereafter, he showed scenes illuminated by artificial light. Painting darkness is technically demanding, and Hopper was con- stantly studying the effects of night light. Emerging from a Cape Cod restaurant one evening, he remarked upon observing some foliage lit by the restaurant window, “Do you notice how artificial trees look at night? Trees look like theater at night.”1 Contemporary critics recognized both the theatrical settings of Hopper’s paintings and the challenge of painting night scenes. -

Edward Hopper 26 January – 26 July 2020

Media release Edward Hopper 26 January – 26 July 2020 Edward Hopper (1882–1967) is widely acknowledged as one of the most significant artists of the 20th century. In Europe, he is known mainly for his oil paintings of urban life scenes dating from the 1920s to 1960s, some of which have become highly popular images. Less attention has so far been paid to his landscapes. Surprisingly, no exhibition to date has dealt comprehensively with Hopper’s approach to American landscape. Initially until 17 May 2020, the Fondation Beyeler presents an extensive exhibition of iconic landscape paintings in oil as well as a selection of watercolors and drawings. This will also be the first time Hopper’s works are shown in an exhibition in German-speaking Switzerland. Hopper was born in Nyack, New York. After training as an illustrator, he studied painting at the New York School of Art until 1906. Next to German, French and Russian literature, the young artist found key reference points in painters such as Diego Velázquez, Francisco de Goya, Gustave Courbet and Édouard Manet. Although Hopper long worked mainly as an illustrator, his fame rests primarily on his oil paintings, which attest to his deep interest in color and his virtuosity in representing light and shadow. Moreover, on the basis of his observations Hopper was able to establish a personal aesthetics that has influenced not only painting but also popular culture, photography and film. The idea for this exhibition arose when Cape Ann Granite, a landscape painted by Edward Hopper in 1928, joined the collection of the Fondation Beyeler as a permanent loan. -

THE WHITNEY to PRESENT HOPPER DRAWING the First In-Depth Study of the Artist’S Working Process

THE WHITNEY TO PRESENT HOPPER DRAWING The First In-Depth Study of the Artist’s Working Process Edward Hopper (1882–1967), Study for Nighthawks, 1941 or 1942. Fabricated chalk and charcoal on paper; 11 1/8 x 15 in. (28.3 x 38.1 cm) Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase and gift of Josephine N. Hopper by exchange 2011.65 © Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper, licensed by the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York NEW YORK, NY, FEBRUARY 21, 2013—This spring, the Whitney Museum celebrates Edward Hopper’s achievements as a draftsman in the first major museum exhibition to focus on the artist’s drawings and working process. Along with many of his most iconic paintings, the exhibition features more than 200 drawings, the most extensive presentation to date of Hopper’s achievement in this medium, pairing suites of preparatory studies and related works with such major oil paintings as New York Movie (1939), Office at Night (1940), Nighthawks (1942) and Morning in a City (1944). The show will be presented in the Museum’s third-floor Peter Norton Family Galleries from May 23 to October 6, before traveling to the Dallas Museum of Art from November 17, 2013 to February 6, 2014 and the Walker Art Center from March 15 to June 22, 2014. Culled from the Museum’s unparalleled collection of the artist’s work, and complemented by key loans, the show illuminates how the artist transformed ordinary subjects—an open road, a city street, an office space, a house, a bedroom—into extraordinary images. -

European Journal of American Studies, 16-1 | 2021 the Empty Stage in Edward Hopper’S Early Sunday Morning, Girlie Show, and Two

European journal of American studies 16-1 | 2021 Spring 2021 The Empty Stage in Edward Hopper’s Early Sunday Morning, Girlie Show, and Two Comedians Philip Smith Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/16694 DOI: 10.4000/ejas.16694 ISSN: 1991-9336 Publisher European Association for American Studies Electronic reference Philip Smith, “The Empty Stage in Edward Hopper’s Early Sunday Morning, Girlie Show, and Two Comedians”, European journal of American studies [Online], 16-1 | 2021, Online since 12 August 2021, connection on 12 August 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ejas/16694 ; DOI: https://doi.org/ 10.4000/ejas.16694 This text was automatically generated on 12 August 2021. Creative Commons License The Empty Stage in Edward Hopper’s Early Sunday Morning, Girlie Show, and Two... 1 The Empty Stage in Edward Hopper’s Early Sunday Morning, Girlie Show, and Two Comedians Philip Smith 1. Hopper and the Stage 1 An empty stage typically signals a moment of transition between the reality the audience occupies outside of the performance and their emersion into the representation of reality presented on the stage. An empty stage at the start of the performance is an invitation for the audience to examine the objects before them and anticipate the action to follow. An empty stage at the end of a performance is an invitation for the audience to reflect upon what they have just seen. This latter moment is captured in one of the most famous passages from The Tempest: Our revels now are ended. These our actors As I foretold you, were all spirits, and Are melted into air, into thin air; And like the baseless fabric of this vision, The cloud-capped towers, the gorgeous palaces, The solemn temples, the great globe itself, Yea all which it inherit, shall dissolve; And, like this insubstantial pageant faded, Leave not a rack behind.