Fitzgerald & Hopper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hopperville Express

Curriculum Units by Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute 1989 Volume V: America as Myth The HopperVille Express Curriculum Unit 89.05.01 by Casey Cassidy This curriculum unit is designed to utilize Edward Hopper’s realistic 20th century paintings as a “vehicle” to transport middle school children from the hills and seasides of New England, through the metropolis of New York City, and across the plains of the western United States. As our unit continues along its journey, it will cross a timeline of approximately forty years which will serve to highlight technological improvements in transportation, changes in period attire, and various architectural styles. We will experience a sense of nostalgia as we view a growing spirit of nationalistic pride as we watch America grow, change, and move forward through the eyes of Edward Hopper. The strategies in this unit will encourage the youngsters to use various skills for learning. Each student will have the opportunity to read, to critically examine slides and lithographs of selected Hopper creations, to fully participate in teacherled discussions of these works of art, and to participate first hand as a commercial artist—i.e. they will be afforded an opportunity to go out into their community, traveling on foot or by car (as Edward Hopper did on countless occasions), to photograph or to sketch buildings, scenes, or structures similar to commonplace areas that Hopper painted himself. In this way, we hope to create a sense of the challenge facing every artist as they themselves seek to create their own masterpieces. Hopper was able “to portray the commonplace and make the ordinary poetic.”1 We hope our students will be able to understand these skills and to become familiar with the decisions, the inconveniences, and the obstacles of every artist as they ply their trade. -

Edward Hopper's Adaptation of the American Sublime

Rhetoric and Redress: Edward Hopper‘s Adaptation of the American Sublime A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Fine Arts Rachael M. Crouch August 2007 This thesis titled Rhetoric and Redress: Edward Hopper’s Adaptation of the American Sublime by RACHAEL M. CROUCH has been approved for the School of Art and the College of Fine Arts by Jeannette Klein Assistant Professor of Art History Charles A. McWeeny Dean, College of Fine Arts Abstract CROUCH, RACHAEL M., M.F.A., August 2007, Art History Rhetoric and Redress: Hopper’s Adaptation of the American Sublime (80 pp.) Director of Thesis: Jeannette Klein The primary objective of this thesis is to introduce a new form of visual rhetoric called the “urban sublime.” The author identifies certain elements in the work of Edward Hopper that suggest a connection to earlier American landscape paintings, the pictorial conventions of which locate them within the discursive formation of the American Sublime. Further, the widespread and persistent recognition of Hopper’s images as unmistakably American, links them to the earlier landscapes on the basis of national identity construction. The thesis is comprised of four parts: First, the definitional and methodological assumptions of visual rhetoric will be addressed; part two includes an extensive discussion of the sublime and its discursive appropriation. Part three focuses on the American Sublime and its formative role in the construction of -

The Mind in Motion: Hopper's Women Through Sartre's Existential Freedom

Intercultural Communication Studies XXIV(1) 2015 WANG The Mind in Motion: Hopper’s Women through Sartre’s Existential Freedom Zhenping WANG University of Louisville, USA Abstract: This is a study of the cross-cultural influence of Jean-Paul Sartre on American painter Edward Hopper through an analysis of his women in solitude in his oil paintings, particularly the analysis of the mind in motion of these figures. Jean-Paul Sartre was a twentieth century French existentialist philosopher whose theory of existential freedom is regarded as a positive thought that provides human beings infinite possibilities to hope and to create. His philosophy to search for inner freedom of an individual was delivered to the US mainly through his three lecture visits to New York and other major cities and the translation by Hazel E. Barnes of his Being and Nothingness. Hopper is one of the finest painters of the twentieth-century America. He is a native New Yorker and an artist who is searching for himself through his painting. Hopper’s women figures are usually seated, standing, leaning forward toward the window, and all are looking deep out the window and deep into the sunlight. These women are in their introspection and solitude. These figures are usually posited alone, but they are not depicted as lonely. Being in outward solitude, they are allowed to enjoy the inward freedom to desire, to imagine, and to act. The dreaming, imagining, expecting are indications of women’s desires, which display their interior possibility or individual agency. This paper is an attempt to apply Sartre’s philosophy to see that these women’s individual agency determines their own identity, indicating the mind in motion. -

Reasons for Moving: Mark Strand on the Art of Edward Hopper1

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Viagens pela Palavra. provided by Repositório Aberto da Universidade Aberta 129 Reasons for Moving: Mark Strand on the Art of Edward Hopper1 Jeffrey Scott Childs Universidade Aberta Edward Hopper’s work has repeatedly been regarded by a range of critics as among the most significant productions of 20th century American art and has been discussed in connection with phenomena as diverse as French symbolism (both in poetry and painting), the work of Piet Mondrian and of the so-called ash can school, as well as viewed as a forerunner of both pop art and abstract expressionism. A recent exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art included several of Hopper’s paintings under the rubric of “Figurative Expressionism.”1 If this description is less than helpful in critically locating Hopper’s work, I hope it will suggest some of the complexities inherent in coming to terms with his art and encourage viewers to look at it from a variety of different perspectives, which, as I hope to show, is one of Hopper’s most significant projects. Mark Strand is the author of numerous works dating from his first volume of poetry, Sleeping with One Eye Open, published in 1964, to his most recent, Chicken, Shadow, Moon & More, published in 2000. Among these are translations of the poets Raphael Alberti and Carlos Drummond de Andrade, as well as books on painters, such as William Bailey, and painting (which he studied under Josef Albers at the Yale Art School from 1956 to 1959). -

Edward Hopper a Catalogue Raisonne

Edward Hopper A Catalogue Raisonne Volume III Oils Gail Levin Whitney Museum of American Art, New York in associalion wilh W. W. Norton & Company, New York • London American Village, 1912 (0-183) City, The, ig27 (0-252) Index of Titles Apartment Houses, 1923 (0-242) City Hoofs, ig32 (0-288) [Apartment Houses, Harlem River], City Sunlight, 1954 (0-550) Oils c. 1930(0-275) [Clamdigger], 1^55(0-297) Approaching a City, 1946 (0-332) Coast Guard Station, 1929(0-267) Apres midi de Juin or L'apres midi de [Cobb's Barns und Distant Houses], 1930-35 Prinletnps, 1907 (0-143) (0-278) [Artist's Bedroom, NyackJ, c. 1905-06 [Cobb's Barns, South Truro], 1950-55 (0-122) (0-279) [Artist's Bedroom, Nyack, The], c. 1905- Compartment C, Car 293, 1938 (0-506) 06 (0-121) Conference at Night, ig4g (0-338) [Artist Sealed at Easel]', igo3~o6 (0-84) [Copy after Edouard Manet's Woman with August in the City, 1945 (0-329) a Parrot], c. 1902-03 (0-19) Automat, 1927 (0-251) CornBeltCity 1947 (0-554) Corn Hill, Truro, 1930 (0-272) [Back of Seated Male Nude Model], [Cottage and Fence], c. igo4-o6 (0-97) c. 1902-04 (0-28) [Cottage in Foliage], c. 1 go4-o6 (0-98) Barber Shop, 1931 (0-285) /Country Road], c. 1897 (0-4) /Bedroom], c. 1905-06 (0-124) Cove at Ogunquit, 1914 (0-193) Berge, La (0-171) Bistro, Le or The Wine Shop, 1909 (0-174) Dauphinee House, 1952 (0-286) [Blackhead, Monhegan], 1916-19 (0-220) Dawn Before Gettysburg, 1954 (0-295) [Blackhead, Monhegan], 1916-19 (0-221) Dawn in Pennsylvania, ig42 (0-323) [Blackhead, Monhegan], 1916-19 (0-222) [Don Quixote on Horseback], c. -

Edward Hopper’S (1882–1967) Most Admired Paint- Ings Are Night Scenes

any of Edward Hopper’s (1882–1967) most admired paint- ings are night scenes. An enthusiast of both movies and Mthe theater, he adapted the device of highlighting a scene against a dark background, providing the viewer with a sense of sit- ting in a darkened theater waiting for the drama to unfold. By staging his pictures in darkness, Hopper was able to illuminate the most important features while obscuring extraneous detail. The set- tings in Night Windows, Room in New York, Nighthawks, and other night compositions enhance the emotional content of the works — adding poignancy and suggestions of danger or uneasiness. EDWARD HOPPER by janet l. comey hours of darkness The Nyack, New York, born Hopper trained as an illustrator before transferring to the New York School of Art, where he studied under Ashcan School painter Robert Henri (1869–1929). Near the beginning of his career, he revealed an interest in night scenes. On his first trip to Europe in 1906–07, he was fascinated by Rembrandt’s Night Watch (1642) in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam; writing to his mother that the painting was “the most wonderful thing of [Rembrandt’s] I have seen, it’s past belief in its reality — it almost amounts to deception.” In several early paintings, Hopper depicted rooms and figures in moonlight. Thereafter, he showed scenes illuminated by artificial light. Painting darkness is technically demanding, and Hopper was con- stantly studying the effects of night light. Emerging from a Cape Cod restaurant one evening, he remarked upon observing some foliage lit by the restaurant window, “Do you notice how artificial trees look at night? Trees look like theater at night.”1 Contemporary critics recognized both the theatrical settings of Hopper’s paintings and the challenge of painting night scenes. -

THE WHITNEY to PRESENT HOPPER DRAWING the First In-Depth Study of the Artist’S Working Process

THE WHITNEY TO PRESENT HOPPER DRAWING The First In-Depth Study of the Artist’s Working Process Edward Hopper (1882–1967), Study for Nighthawks, 1941 or 1942. Fabricated chalk and charcoal on paper; 11 1/8 x 15 in. (28.3 x 38.1 cm) Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase and gift of Josephine N. Hopper by exchange 2011.65 © Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper, licensed by the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York NEW YORK, NY, FEBRUARY 21, 2013—This spring, the Whitney Museum celebrates Edward Hopper’s achievements as a draftsman in the first major museum exhibition to focus on the artist’s drawings and working process. Along with many of his most iconic paintings, the exhibition features more than 200 drawings, the most extensive presentation to date of Hopper’s achievement in this medium, pairing suites of preparatory studies and related works with such major oil paintings as New York Movie (1939), Office at Night (1940), Nighthawks (1942) and Morning in a City (1944). The show will be presented in the Museum’s third-floor Peter Norton Family Galleries from May 23 to October 6, before traveling to the Dallas Museum of Art from November 17, 2013 to February 6, 2014 and the Walker Art Center from March 15 to June 22, 2014. Culled from the Museum’s unparalleled collection of the artist’s work, and complemented by key loans, the show illuminates how the artist transformed ordinary subjects—an open road, a city street, an office space, a house, a bedroom—into extraordinary images. -

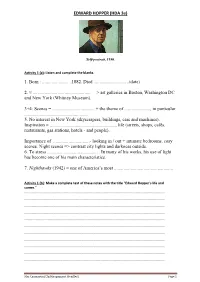

EDWARD HOPPER (HDA 3E)

EDWARD HOPPER (HDA 3e) Self-portrait, 1930. Activity 1 (a): Listen and complete the blanks. 1. Born : ...................... ,1882. Died ..............................(date) 2. ≈ ................................................. => art galleries in Boston, Washington DC and New York (Whitney Museum). 3+4: Scenes = .................................... + the theme of ......................, in particular ...................................................... 5. No interest in New York (skyscrapers, buildings, cars and machines). Inspiration = ......................................................... life (streets, shops, cafés, restaurants, gas stations, hotels - and people). Importance of ...............................- looking in / out + intimate bedrooms, cosy scenes. Night scenes => contrast city lights and darkness outside. 6. To stress ........................................... In many of his works, his use of light has become one of his main characteristics. 7. Nighthawks (1942) = one of America’s most .................................................. Activity 1 (b): Make a complete text of these notes with the title "Edward Hopper's life and career." .............................................................................................................................................. .............................................................................................................................................. ............................................................................................................................................. -

Edward Hopper's Urban Landscapes

© COPYRIGHT by Can Gulan 2014 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED To my mother, father, and aunt. I thank them for always supporting and believing in me. EDWARD HOPPER’S URBAN LANDSCAPES: MODERN EXPERIENCE AND ALIENATION BY Can Gulan ABSTRACT Edward Hopper’s works are generally associated with alienation, but the sources of this feeling are not studied extensively and in a comprehensive manner. Hopper’s representation of deserted and bleak cityscapes focus on loneliness and isolation of urban centers to create this feeling of alienation, which is supported by subtle depictions of dangerous possibilities at night. This alienating modern experience is also related to the transition from rural to urban areas and the resulting adjustment period while this transition creates tensions between nature and civilization in Hopper’s works. Hopper’s use of light is another alienating aspect of his works, especially in artificially lighted scenes. Hopper also focused on new voyeuristic possibilities of urban life and the way he represented these qualities created alienating experiences for the viewers. All these aspects of Hopper’s works are contributing to the feeling of alienation and they are all related to the modern experience. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Helen Langa, who encouraged me throughout this process, helped me to better organize my arguments and supported my ideas with valuable feedbacks. I would also like to thank Dr. Juliet Bellow and Dr. Andrea Pearson for their contributions. Finally, I would like to thank all art history faculty and fellow graduate students of American University for the friendly and supportive atmosphere. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................... -

EDWARD HOPPER's BLACK SUN Arthur Kroker

Canadian Journal of Political and Social Theory/Revue canadienne de theorie politique et sociale, Volume X. N. 1-2 (1986) . THE AESTHETICS OF SEDUCTION: EDWARD HOPPER'S BLACK SUN Arthur Kroker Edward Hopper is the American painter of technicisme. If by techni- cisme is meant an urgent belief in the historical inevitability of the fully realized technological society and, if further, technicisme is understood to be the guiding impulse of the American Republic, at least since the incep- tion of the United States as a society with no history before the age of progress, then Hopper is that curiosity of an American artist who, breaking decisively with the equation of technology and freedom in the American mind, went over instead to the alternative vision of technology as depriva- tion. Quantum Physics as Decline There is, in particular, one painting by Hopper which reveals fully the price which is exacted for admission to the fully realized technological society, and which speaks directly to the key issue of technology and power in the postmodern condition. Titled simply, yet evocatively, Rooms by the Sea, the painting consists simply of two rooms which are linked only by an aesthetic symmetry of form (the perfectly parallel rays of sunlight) ; which are empty (there are no human presences) and also perfectly still (the vacancy of the sea without is a mirror-image of the deadness within). Everything in the painting is transparent, nameless, relational and seduc- tive; and, for just that reason, the cumulative emotional effect of the painting is one of anxiety and dread. Rooms by the Sea is an emblematic image of technology and culture as degeneration : nature (the sea) and culture (the rooms) are linked only accidentally in a field of purely spatial contiguity; all human presences have been expelled and, consequently, the ARTHUR KROKER Edward Hopper, Room- by the Sea question of the entanglement of identity and technique never arises; and a menacing mood of aesthetic symmetry is the keynote feature. -

Hopper's Cool: Modernism and Emotional Restraint

Hopper’s Cool Modernism and Emotional Restraint Erika Doss Edward Hopper remains one of America’s most celebrated modern artists. Contemporary exhibitions of his work are guaranteed blockbusters: the Whitney Museum of American Art’s 2010–11 survey Modern Life: Edward Hopper and His Time drew “enormously high crowds,” observes the curator Barbara Haskell.1 So did the Bowdoin College Museum of Art’s smaller 2011 show, Edward Hopper’s Maine. Attendance fgures in Europe have been astounding: in Madrid in 2012, a Hopper retrospective organized by the Museo Tyssen- Bornemisza was seen by 322,437 people, setting a museum record. Audiences in Paris waited up to four hours to enter the same exhibition when it traveled to the Grand Palais, where “Hopper mania” drove the museum to extend its run by fve days (with 24/7 acces- sibility during the last weekend) so that overfow crowds could view paintings such as Hotel Room (1931, frontispiece) and Nighthawks (see fg. 2). More than 784,000 people attended the exhibition in Paris, outstripping the numbers for the museum’s previously most popular show, Picasso and the Masters, in 2008–9.2 What accounts for Hopper’s widespread recognition today? Te scenes and subjects he painted, from isolated houses and industrial landscapes to fgures perched on beds in bleak hotel rooms or sitting silently in all-night diners, are unremarkable, even banal; his painting style is reserved. Tis essay argues that Hopper’s enduring appeal relates to his visualization of modern American feeling and, in particular, his navigation of an “emotional regime” that governed twentieth-century American life. -

GRADUATE RESEARCH PAPER ART HISTORY AR 311 American Art II

GRADUATE RESEARCH PAPER ART HISTORY AR 311 American Art II NATURALISM OF HOPPER, SOYER, AND SRAHN IN COMPARISON WITH WRITINGS BY ANDERSON, DREISER, AND NORRIS by Alice Kurtz Vogt Colorado State University Spring Semester 1979 Naturalism is as much a way of thinking about the world as of representing it. I intend to describe and illustrate naturalism of the twentieth century. Edward Hopper, Raphael Soyer, and Ben Shahn present distinct and personal ways of mirroring that something called nature. Hopper, Soyer and Shahn exemplify naturalism in three different ways, yet with a thread of continuity. Their work will be illustrated by photographs with additional support shown by the literary naturalists, Sherwood Anderson, Theodore Dreiser and Frank Norris. In 1900, America could look back on a phenomenal half-century of progress. Vast fortunes had been accumulated and a whole new urban, industrial population had been created. The conflicts and inequities brought by our astute industrial growth were expressed in an art and literature of protest under the auspices of naturalism. Except for its subject matter, American painting until early in the twentieth century had not in any essential way been distinguishable from European. Cole, Homer and Eakins adopted modes of vision that were fundamentally European and used them successfully to interpret specific American experiences. During the first half of the twentieth century this situation was gradually reduced and reversed. In 1900 the artistic expression was considered provincial and timid, but by 1950 the antithesis of this was prevalent. American artists and ~heir public slowly became more acutely aware of European modernism and they found ways to equate new techniques with their continuing desire to produce and progress as well as to record what life in this country had been like.