Pardo Garcia2020.Pdf (13.56Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hopperville Express

Curriculum Units by Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute 1989 Volume V: America as Myth The HopperVille Express Curriculum Unit 89.05.01 by Casey Cassidy This curriculum unit is designed to utilize Edward Hopper’s realistic 20th century paintings as a “vehicle” to transport middle school children from the hills and seasides of New England, through the metropolis of New York City, and across the plains of the western United States. As our unit continues along its journey, it will cross a timeline of approximately forty years which will serve to highlight technological improvements in transportation, changes in period attire, and various architectural styles. We will experience a sense of nostalgia as we view a growing spirit of nationalistic pride as we watch America grow, change, and move forward through the eyes of Edward Hopper. The strategies in this unit will encourage the youngsters to use various skills for learning. Each student will have the opportunity to read, to critically examine slides and lithographs of selected Hopper creations, to fully participate in teacherled discussions of these works of art, and to participate first hand as a commercial artist—i.e. they will be afforded an opportunity to go out into their community, traveling on foot or by car (as Edward Hopper did on countless occasions), to photograph or to sketch buildings, scenes, or structures similar to commonplace areas that Hopper painted himself. In this way, we hope to create a sense of the challenge facing every artist as they themselves seek to create their own masterpieces. Hopper was able “to portray the commonplace and make the ordinary poetic.”1 We hope our students will be able to understand these skills and to become familiar with the decisions, the inconveniences, and the obstacles of every artist as they ply their trade. -

Helsinki in Early Twentieth-Century Literature Urban Experiences in Finnish Prose Fiction 1890–1940

lieven ameel Helsinki in Early Twentieth-Century Literature Urban Experiences in Finnish Prose Fiction 1890–1940 Studia Fennica Litteraria The Finnish Literature Society (SKS) was founded in 1831 and has, from the very beginning, engaged in publishing operations. It nowadays publishes literature in the fields of ethnology and folkloristics, linguistics, literary research and cultural history. The first volume of the Studia Fennica series appeared in 1933. Since 1992, the series has been divided into three thematic subseries: Ethnologica, Folkloristica and Linguistica. Two additional subseries were formed in 2002, Historica and Litteraria. The subseries Anthropologica was formed in 2007. In addition to its publishing activities, the Finnish Literature Society maintains research activities and infrastructures, an archive containing folklore and literary collections, a research library and promotes Finnish literature abroad. Studia fennica editorial board Pasi Ihalainen, Professor, University of Jyväskylä, Finland Timo Kaartinen, Title of Docent, Lecturer, University of Helsinki, Finland Taru Nordlund, Title of Docent, Lecturer, University of Helsinki, Finland Riikka Rossi, Title of Docent, Researcher, University of Helsinki, Finland Katriina Siivonen, Substitute Professor, University of Helsinki, Finland Lotte Tarkka, Professor, University of Helsinki, Finland Tuomas M. S. Lehtonen, Secretary General, Dr. Phil., Finnish Literature Society, Finland Tero Norkola, Publishing Director, Finnish Literature Society Maija Hakala, Secretary of the Board, Finnish Literature Society, Finland Editorial Office SKS P.O. Box 259 FI-00171 Helsinki www.finlit.fi Lieven Ameel Helsinki in Early Twentieth- Century Literature Urban Experiences in Finnish Prose Fiction 1890–1940 Finnish Literature Society · SKS · Helsinki Studia Fennica Litteraria 8 The publication has undergone a peer review. The open access publication of this volume has received part funding via a Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation grant. -

Edward Hopper, Landscape, and Literature

Edward Hopper, Landscape, and Literature Gail LEVIN The art of Edward Hopper, the American realist painter, contains many clues that allow us to trace his interest in literature, which in turn helps to characterize his particular brand of realism. 1) Signs of Hopper’s engagement with literature emerge already in his boyhood. Born in 1882, Hopper grew up in Nyack, New York, a town on the Hudson River, some forty miles north of New York City, where he went to attend art school and lived as an adult, until his death in 1967, shortly before his eighty-fifth birthday. Among the early indications that literature affected Hopper is a plaque that he designed for a Boys’ Yacht Club, which he formed together with three pals. Hopper designed this plaque with the names of the members’ boats. While the other boys chose female names that were upbeat and innocuous, Edward’s choice, Water Witch (Fig. 1), telegraphs an effect of reading on his imagination. He took the name for his boat from The Water- Witch, James Fenimore Cooper’s 1830 novel that tells how the “exploits, mysterious character, and daring of the Water-Witch, and of him who sailed her, were in that day, the frequent subjects of anger, admiration and surprise.... ” 2) His boyhood interest led Hopper to build not only a sailboat but a canoe. Later he would remark, “I thought at one time I’d like to be a naval architect because I am interested in boats, but I got to be a Fig. 1: Edward Hopper, Water Witch on painter instead.” 3) His interest in nautical life sign, Private Collection. -

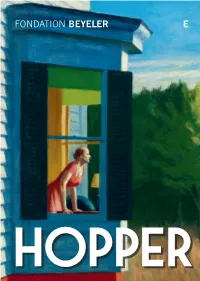

Room Guide Edward Hopper

FONDATION BEYELER E EDWARD HOPPER INTRODUCTION 26 January – 17 May 2020 Edward Hopper (1882–1967) is one of the great familiar yet ultimately little known exponents of modern art. Some of his works have become exceptionally popular and belong to the cultural memory of our age. Yet some aspects of his work are known only to a few specialists. Many of his paintings, as well as his watercolors and drawings, thus remain to be discovered. Our exhibition makes an important contribution in this respect. For the first time, it brings together Hopper’s landscapes, including urban landscapes, providing visitors with deep insights into the artist’s external and internal worlds. Renowned filmmaker Wim Wenders, a long-time, self-avowed Hopper fan, has created a personal tribute to Cover: Edward Hopper the artist, the 3D film Two or Three Things I Know about Cape Cod Morning, 1950 (detail) Edward Hopper, specially for the exhibition at the Oil on canvas, 86.7 x 102.3 cm Smithsonian American Art Museum Fondation Beyeler. Starting with motifs from Hopper’s © Heirs of Josephine Hopper / 2020 ProLitteris, Zurich. pictures, he revives the artist’s characteristic melancholy Photo: Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gene Young mood. The film is screened in the last room of the exhibition. We hope you enjoy the exhibition and would be delighted for you to share your experience with others. ROOM 1 ROOM 2 1 2 Railroad Sunset, 1929 Square Rock, Ogunquit, 1914 Railroad Sunset shows the passage from day into night, Like Edward Hopper’s other landscape paintings, this an evening sky displaying striking light and color mood. -

With His Art and Legacies Edward Hopper

Güzel Sanatlar Fakültesi Dergisi, 2020, Cilt 2, Sayı 2, 173-184 WITH HIS ART AND LEGACIES EDWARD HOPPER Ufuk ÇETİN1 Abstract The works of Edward Hopper, one of the most important artists of America in the 20th century, are universal. Its impressive content is emotionally explained to the lives at the contemporary audience. He illustrates moments and more significantly, characters nearly every viewer can instantly know. There is no ambiguity inside Hopper’s works in a visual cultural way. He impacted lots of artists, photographers, filmmakers, set designers, dancers, writers, and his effect has touched many artists like Rothko, Segal and Oursler, who work with different mediums. He is an interesting artist in the way of impressing nearly all photographers from Arbus to Eggleston. Including Mendes, Lynch and Welles, generations have been inspired from Hopper’s dramatic viewpoints, lighting, and moods. His painting, “Residence by the Railroad” (1925) stimulated Alfred Hitchcock’s house in Psycho (1960) as well as that in Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven (1978). This article introduces the artist with some examples of his personality and samples from his works. Hopper’s paintings are attractive to some writers and musicians. For instance, Tom Waits made an album known as “Nighthawks on the Diner”. Also, Madonna selected a name for a live performance tour after Hooper’s “Girlie Display”. Keywords: Painting, Edward Hopper, American art, landscape painting, visual culture. 1 Öğr. Gör. Dr. Tekirdağ Namık Kemal Üniversitesi, Çorlu Mühendislik Fakültesi, Bilgisayar Mühendisliği Bölümü, [email protected], https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5102-8183 174 Ufuk ÇETİN Sanatı ve Efsaneleriyle Edward Hopper Özet Amerika’nın 20. -

Julius S. Held Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3g50355c No online items Finding aid for the Julius S. Held papers, ca. 1921-1999 Isabella Zuralski. Finding aid for the Julius S. Held 990056 1 papers, ca. 1921-1999 Descriptive Summary Title: Julius S. Held papers Date (inclusive): ca. 1918-1999 Number: 990056 Creator/Collector: Held, Julius S (Julius Samuel) Physical Description: 168 box(es)(ca. 70 lin. ft.) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Research papers of Julius Samuel Held, American art historian renowned for his scholarship in 16th- and 17th-century Dutch and Flemish art, expert on Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. The ca. 70 linear feet of material, dating from the mid-1920s to 1999, includes correspondence, research material for Held's writings and his teaching and lecturing activities, with extensive travel notes. Well documented is Held's advisory role in building the collection of the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico. A significant portion of the ca. 29 linear feet of study photographs documents Flemish and Dutch artists from the 15th to the 17th century. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English Biographical / Historical Note The art historian Julius Samuel Held is considered one of the foremost authorities on the works of Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. -

Edward Hopper's Adaptation of the American Sublime

Rhetoric and Redress: Edward Hopper‘s Adaptation of the American Sublime A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Fine Arts Rachael M. Crouch August 2007 This thesis titled Rhetoric and Redress: Edward Hopper’s Adaptation of the American Sublime by RACHAEL M. CROUCH has been approved for the School of Art and the College of Fine Arts by Jeannette Klein Assistant Professor of Art History Charles A. McWeeny Dean, College of Fine Arts Abstract CROUCH, RACHAEL M., M.F.A., August 2007, Art History Rhetoric and Redress: Hopper’s Adaptation of the American Sublime (80 pp.) Director of Thesis: Jeannette Klein The primary objective of this thesis is to introduce a new form of visual rhetoric called the “urban sublime.” The author identifies certain elements in the work of Edward Hopper that suggest a connection to earlier American landscape paintings, the pictorial conventions of which locate them within the discursive formation of the American Sublime. Further, the widespread and persistent recognition of Hopper’s images as unmistakably American, links them to the earlier landscapes on the basis of national identity construction. The thesis is comprised of four parts: First, the definitional and methodological assumptions of visual rhetoric will be addressed; part two includes an extensive discussion of the sublime and its discursive appropriation. Part three focuses on the American Sublime and its formative role in the construction of -

Eli Siegel - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Eli Siegel - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Eli Siegel(16 August 1902 - 8 November 1978) Eli Siegel was the poet and critic who founded the philosophy Aesthetic Realism in 1941. He wrote the award-winning poem, "Hot Afternoons Have Been in Montana", two highly acclaimed volumes of poetry, a critical consideration of Henry James's The Turn of the Screw titled James and the Children, and Self and World: An Explanation of Aesthetic Realism. <b>Life</b> Born in Latvia, Siegel's family came to the United States when he was an infant. He grew up in Baltimore, Maryland, where he graduated from the Baltimore City College high school, and lived most of his life in New York City. In 1925, his "Hot Afternoons Have Been in Montana" was selected from four thousand anonymously submitted poems as the winner of The Nation's esteemed poetry prize. The magazine's editors described it as "the most passionate and interesting poem which came in—a poem recording through magnificent rhythms a profound and important and beautiful vision of the earth on which afternoons and men have always existed." The poem begins: Quiet and green was the grass of the field, The sky was whole in brightness, And O, a bird was flying, high, there in the sky, So gently, so carelessly and fairly. "Hot Afternoons" was controversial; the author's innovative technique in this long, free-verse poem tended to polarize commentators, with much of the criticism taking the form of parody. -

Edward Hopper___Book Design

1882-1967 Coverafbeelding: Hotel Lobby, 1943 Olieverf op linnen, 81,9 x 103,5 cm The Indianapolis Museum of Art, herdenkingscollectie William Ray Adams Self-portrait, 1925-1930 Self-portrait by Edward Hopper, 1906 Olieverf op linnen, 63,8x51,4cm Olieverf op linnen New York, Collection of Whitney Museum of American Art New York, Collection of Whitney Museum of American Art 2 3 De tweede voorbode van latere ontwikkelingspatronen Soir Blue uit 1914 laat het late werk vanuit een derde is te zien in Hoppers landschapschilderijen, die vooral perspectief zien. Aan de ene kant kan dit schilderij al EEN VOORZICHTIG BEGIN kenmerkend zijn voor de overgang van de impressionis- terugblik van de schilder op zijn Franse en impressionis- tische (Franse) naar de vroege Amerikaanse periode. tische periode opgevat worden, maar bovendien verwijst Al heel vroeg verschijnen er naast de zuivere landschap- het door zijn psychologische laag naar toekomstige doe- schilderijen composities waarin natuur en beschaving in ken. Er kan gesteld worden dat Hopper vanaf dit mo- elkaar overlopen en tegelijk haarscherp van elkaar zijn ment niet allen zijn identiteit als Amerikaans kunstenaar, Edward Hopper wordt op 22 juli 1882 geboren in New afgegrensd. Steeds weer schildert Hopper bruggen, ka- maar ook de psychogrammatische laag in zijn schilde- York. Hij studeerde er aan de Newyorkse kunstacade- nalen, aanlegplaatsen voor boten en vuurtorens. rijen gaat benadrukken. mie als illustrator maar gaat na een jaar over naar The New York School of Art. Eerst volgt hij hier reclame, la- ter leert hij de schilderkunst van docenten Robert Henri en Keneth Hayes Miller. Afgezien van twee korte bezoeken aan Europa leeft Edward Hopper vanaf 1908 in New York. -

November 12, 2013

volume 14 - issue 11 - tuesday, november, 12, 2013 - uvm, burlington, vt uvm.edu/~watertwr - thewatertower.tumblr.com by mikaelawaters by dustineagar Forgive me UVM, for I have sinned. After four years in a Catholic high Russia has been in the news quite a bit school and a subsequent lately. Allegations of skullduggery at the vow to never again partici- recent G-20 conference, a hardline stance pate in organized religion, against UN intervention into the humani- I confess to believing in a tarian crisis in Syria, an uncharacteristic higher power. Dare I say embrace of NSA leader Edward Snowden, it? After suffering through and a flex of military muscle in the Arctic countless masses, endless have combined with many other episodes religion classes, and a com- in recent years to elevate tensions between plete memorization of both Mother Russia and her capitalist cousins. the Hail Mary and the Our The house Stalin built has likened itself Father in Latin, I confess to that kid in your neighborhood who is to having a different reli- always getting in trouble—whenever the gion. This religion, power- name comes up you wonder what sort of ful enough to seize my heart half-witted shenanigans have irritated the and bring me back into the community this time. More recently, prob- fold, is Coffee. ably since mass protests erupted in Mos- As definitively sacrile- cow over allegations of election fraud in gious and questionably ab- December 2011, Russia has been throwing surd as this confession may a hissy-fit of global proportion. sound, my relationship with In September, the Russian Navy ar- coffee conforms to the basic rested 30 people at gunpoint aboard the structure of conventional re- Dutch-flagged ship “Arctic Sunrise”. -

Alienation in Edward Hopper's and Jackson Pollock's

ALIENATION IN EDWARD HOPPER’S AND JACKSON POLLOCK’S PAINTINGS: A COMPARISON AND CONTRAST A Thesis by Zohreh Dalirian Bachelor of Fine Arts, Shahed University, 2005 Submitted to the Department of Liberal Arts and Sciences and the faculty of the Graduate School of Wichita State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts May 2010 © Copyright 2010 by Zohreh Dalirian All Rights Reserved ALIENATION IN EDWARD HOPPER’S AND JACKSON POLLOCK’S PAINTINGS: A COMPARISON AND CONTRAST The following faculty members have examined the final copy of this thesis for form and content, and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts with a major in Liberal Studies. _________________________________ Dorothy Billings, Committee Chair _________________________________ David Soles, Committee Member __________________________________ Mary Sue Foster, Committee Member iii DEDICATION To my lovely mother, my dear husband, and the memory of my father. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to extend my gratitude to committee chair, Dr. Dorothy Billings, for encouraging me to develop my ideas, and my advisor, Dr. Soles, who supported me during my degree program, and also Professor Foster for serving on my thesis committee and for her valuable comments. I am very grateful to my father, who passed away a few days before my thesis defense, and my mother and my sisters for their impeccable help and support. Finally, I would like to express my exclusive appreciation to my beloved husband, Ruhola, who supported me from the beginning to the very end. v ABSTRACT In this thesis I study alienation in Edward Hopper’s and Jackson Pollack’s paintings. -

Why Attacks on Public Employee Unions Are on the Rise!

NH Labor News Progressive Politics, News & Information from a Labor Perspective MARCH 6, 2015 NHlabornews.com • New Hampshire Why Attacks on Public Employee Unions Are on the Rise! By Steven Weiner workers have lost their jobs, union-busting is rampant, and in- creasing numbers of Americans are struggling in desperate In recent years throughout America, there have been massive at- poverty. tacks on public employees and the unions that represent them. The latest salvo has come from the newly elected governor of Illi- In an issue of The Right of Aesthetic Realism to Be Known, Ellen nois, Bruce Rauner, who, in the name of “fiscal austerity,” issued Reiss explains: an executive order that bars public sector unions from requiring “Because of this failure of business based on private profit, workers they represent to pay fees (often called “fair share pay- there has been a huge effort in the last decade to privatize ments”) to the union. This means that a worker can benefit from publicly run institutions. The technique is to disseminate mas- a union’s collective bargaining with respect to wages, health in- sive propaganda against the public institutions, and also do surance, pensions and job protections, while not financially sup- what one can to make them fail, including through withhold- porting the union by paying their fair share. The purpose behind ing funding from them. Eminent among such institutions are this measure is described by Roberta Lynch, Executive Director the public schools and the post office. The desire is to place of AFSCME Council 31: them in private hands—not for the public good, not so that “I was shocked by the breadth of his assault on labor….It’s the American people can fare well—but to keep profit eco- not limited to public sector unions.