Edward Hopper: the Master of Urban Isolation in a New Online Show | Financial Times 27.04.20, 08�23

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Room Guide Edward Hopper

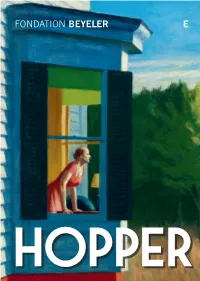

FONDATION BEYELER E EDWARD HOPPER INTRODUCTION 26 January – 17 May 2020 Edward Hopper (1882–1967) is one of the great familiar yet ultimately little known exponents of modern art. Some of his works have become exceptionally popular and belong to the cultural memory of our age. Yet some aspects of his work are known only to a few specialists. Many of his paintings, as well as his watercolors and drawings, thus remain to be discovered. Our exhibition makes an important contribution in this respect. For the first time, it brings together Hopper’s landscapes, including urban landscapes, providing visitors with deep insights into the artist’s external and internal worlds. Renowned filmmaker Wim Wenders, a long-time, self-avowed Hopper fan, has created a personal tribute to Cover: Edward Hopper the artist, the 3D film Two or Three Things I Know about Cape Cod Morning, 1950 (detail) Edward Hopper, specially for the exhibition at the Oil on canvas, 86.7 x 102.3 cm Smithsonian American Art Museum Fondation Beyeler. Starting with motifs from Hopper’s © Heirs of Josephine Hopper / 2020 ProLitteris, Zurich. pictures, he revives the artist’s characteristic melancholy Photo: Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gene Young mood. The film is screened in the last room of the exhibition. We hope you enjoy the exhibition and would be delighted for you to share your experience with others. ROOM 1 ROOM 2 1 2 Railroad Sunset, 1929 Square Rock, Ogunquit, 1914 Railroad Sunset shows the passage from day into night, Like Edward Hopper’s other landscape paintings, this an evening sky displaying striking light and color mood. -

The Mind in Motion: Hopper's Women Through Sartre's Existential Freedom

Intercultural Communication Studies XXIV(1) 2015 WANG The Mind in Motion: Hopper’s Women through Sartre’s Existential Freedom Zhenping WANG University of Louisville, USA Abstract: This is a study of the cross-cultural influence of Jean-Paul Sartre on American painter Edward Hopper through an analysis of his women in solitude in his oil paintings, particularly the analysis of the mind in motion of these figures. Jean-Paul Sartre was a twentieth century French existentialist philosopher whose theory of existential freedom is regarded as a positive thought that provides human beings infinite possibilities to hope and to create. His philosophy to search for inner freedom of an individual was delivered to the US mainly through his three lecture visits to New York and other major cities and the translation by Hazel E. Barnes of his Being and Nothingness. Hopper is one of the finest painters of the twentieth-century America. He is a native New Yorker and an artist who is searching for himself through his painting. Hopper’s women figures are usually seated, standing, leaning forward toward the window, and all are looking deep out the window and deep into the sunlight. These women are in their introspection and solitude. These figures are usually posited alone, but they are not depicted as lonely. Being in outward solitude, they are allowed to enjoy the inward freedom to desire, to imagine, and to act. The dreaming, imagining, expecting are indications of women’s desires, which display their interior possibility or individual agency. This paper is an attempt to apply Sartre’s philosophy to see that these women’s individual agency determines their own identity, indicating the mind in motion. -

Edward Hopper a Catalogue Raisonne

Edward Hopper A Catalogue Raisonne Volume III Oils Gail Levin Whitney Museum of American Art, New York in associalion wilh W. W. Norton & Company, New York • London American Village, 1912 (0-183) City, The, ig27 (0-252) Index of Titles Apartment Houses, 1923 (0-242) City Hoofs, ig32 (0-288) [Apartment Houses, Harlem River], City Sunlight, 1954 (0-550) Oils c. 1930(0-275) [Clamdigger], 1^55(0-297) Approaching a City, 1946 (0-332) Coast Guard Station, 1929(0-267) Apres midi de Juin or L'apres midi de [Cobb's Barns und Distant Houses], 1930-35 Prinletnps, 1907 (0-143) (0-278) [Artist's Bedroom, NyackJ, c. 1905-06 [Cobb's Barns, South Truro], 1950-55 (0-122) (0-279) [Artist's Bedroom, Nyack, The], c. 1905- Compartment C, Car 293, 1938 (0-506) 06 (0-121) Conference at Night, ig4g (0-338) [Artist Sealed at Easel]', igo3~o6 (0-84) [Copy after Edouard Manet's Woman with August in the City, 1945 (0-329) a Parrot], c. 1902-03 (0-19) Automat, 1927 (0-251) CornBeltCity 1947 (0-554) Corn Hill, Truro, 1930 (0-272) [Back of Seated Male Nude Model], [Cottage and Fence], c. igo4-o6 (0-97) c. 1902-04 (0-28) [Cottage in Foliage], c. 1 go4-o6 (0-98) Barber Shop, 1931 (0-285) /Country Road], c. 1897 (0-4) /Bedroom], c. 1905-06 (0-124) Cove at Ogunquit, 1914 (0-193) Berge, La (0-171) Bistro, Le or The Wine Shop, 1909 (0-174) Dauphinee House, 1952 (0-286) [Blackhead, Monhegan], 1916-19 (0-220) Dawn Before Gettysburg, 1954 (0-295) [Blackhead, Monhegan], 1916-19 (0-221) Dawn in Pennsylvania, ig42 (0-323) [Blackhead, Monhegan], 1916-19 (0-222) [Don Quixote on Horseback], c. -

American Paintings, 1900–1945

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS American Paintings, 1900–1945 American Paintings, 1900–1945 Published September 29, 2016 Generated September 29, 2016 To cite: Nancy Anderson, Charles Brock, Sarah Cash, Harry Cooper, Ruth Fine, Adam Greenhalgh, Sarah Greenough, Franklin Kelly, Dorothy Moss, Robert Torchia, Jennifer Wingate, American Paintings, 1900–1945, NGA Online Editions, http://purl.org/nga/collection/catalogue/american-paintings-1900-1945/2016-09-29 (accessed September 29, 2016). American Paintings, 1900–1945 © National Gallery of Art, Washington National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS American Paintings, 1900–1945 CONTENTS 01 American Modernism and the National Gallery of Art 40 Notes to the Reader 46 Credits and Acknowledgments 50 Bellows, George 53 Blue Morning 62 Both Members of This Club 76 Club Night 95 Forty-two Kids 114 Little Girl in White (Queenie Burnett) 121 The Lone Tenement 130 New York 141 Bluemner, Oscar F. 144 Imagination 152 Bruce, Patrick Henry 154 Peinture/Nature Morte 164 Davis, Stuart 167 Multiple Views 176 Study for "Swing Landscape" 186 Douglas, Aaron 190 Into Bondage 203 The Judgment Day 221 Dove, Arthur 224 Moon 235 Space Divided by Line Motive Contents © National Gallery of Art, Washington National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS American Paintings, 1900–1945 244 Hartley, Marsden 248 The Aero 259 Berlin Abstraction 270 Maine Woods 278 Mount Katahdin, Maine 287 Henri, Robert 290 Snow in New York 299 Hopper, Edward 303 Cape Cod Evening 319 Ground Swell 336 Kent, Rockwell 340 Citadel 349 Kuniyoshi, Yasuo 352 Cows in Pasture 363 Marin, John 367 Grey Sea 374 The Written Sea 383 O'Keeffe, Georgia 386 Jack-in-Pulpit - No. -

EDWARD HOPPER's BLACK SUN Arthur Kroker

Canadian Journal of Political and Social Theory/Revue canadienne de theorie politique et sociale, Volume X. N. 1-2 (1986) . THE AESTHETICS OF SEDUCTION: EDWARD HOPPER'S BLACK SUN Arthur Kroker Edward Hopper is the American painter of technicisme. If by techni- cisme is meant an urgent belief in the historical inevitability of the fully realized technological society and, if further, technicisme is understood to be the guiding impulse of the American Republic, at least since the incep- tion of the United States as a society with no history before the age of progress, then Hopper is that curiosity of an American artist who, breaking decisively with the equation of technology and freedom in the American mind, went over instead to the alternative vision of technology as depriva- tion. Quantum Physics as Decline There is, in particular, one painting by Hopper which reveals fully the price which is exacted for admission to the fully realized technological society, and which speaks directly to the key issue of technology and power in the postmodern condition. Titled simply, yet evocatively, Rooms by the Sea, the painting consists simply of two rooms which are linked only by an aesthetic symmetry of form (the perfectly parallel rays of sunlight) ; which are empty (there are no human presences) and also perfectly still (the vacancy of the sea without is a mirror-image of the deadness within). Everything in the painting is transparent, nameless, relational and seduc- tive; and, for just that reason, the cumulative emotional effect of the painting is one of anxiety and dread. Rooms by the Sea is an emblematic image of technology and culture as degeneration : nature (the sea) and culture (the rooms) are linked only accidentally in a field of purely spatial contiguity; all human presences have been expelled and, consequently, the ARTHUR KROKER Edward Hopper, Room- by the Sea question of the entanglement of identity and technique never arises; and a menacing mood of aesthetic symmetry is the keynote feature. -

GRADUATE RESEARCH PAPER ART HISTORY AR 311 American Art II

GRADUATE RESEARCH PAPER ART HISTORY AR 311 American Art II NATURALISM OF HOPPER, SOYER, AND SRAHN IN COMPARISON WITH WRITINGS BY ANDERSON, DREISER, AND NORRIS by Alice Kurtz Vogt Colorado State University Spring Semester 1979 Naturalism is as much a way of thinking about the world as of representing it. I intend to describe and illustrate naturalism of the twentieth century. Edward Hopper, Raphael Soyer, and Ben Shahn present distinct and personal ways of mirroring that something called nature. Hopper, Soyer and Shahn exemplify naturalism in three different ways, yet with a thread of continuity. Their work will be illustrated by photographs with additional support shown by the literary naturalists, Sherwood Anderson, Theodore Dreiser and Frank Norris. In 1900, America could look back on a phenomenal half-century of progress. Vast fortunes had been accumulated and a whole new urban, industrial population had been created. The conflicts and inequities brought by our astute industrial growth were expressed in an art and literature of protest under the auspices of naturalism. Except for its subject matter, American painting until early in the twentieth century had not in any essential way been distinguishable from European. Cole, Homer and Eakins adopted modes of vision that were fundamentally European and used them successfully to interpret specific American experiences. During the first half of the twentieth century this situation was gradually reduced and reversed. In 1900 the artistic expression was considered provincial and timid, but by 1950 the antithesis of this was prevalent. American artists and ~heir public slowly became more acutely aware of European modernism and they found ways to equate new techniques with their continuing desire to produce and progress as well as to record what life in this country had been like. -

Robert Frost's "Nighthawks"/ Edward Hopper's "Desert Places"

Colby Quarterly Volume 24 Issue 1 March Article 5 March 1988 Robert Frost's "Nighthawks"/ Edward Hopper's "Desert Places" Paul Strong Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, Volume 24, no.1, March 1988, p.27-35 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Strong: Robert Frost's "Nighthawks"/ Edward Hopper's "Desert Places" Robert Frost's "Nighthawks"/ Edward Hopper's "Desert Places" by PAUL STRONG HE FIRST few months of 1913 were singular times for Robert Frost and TEdward Hopper. Robert and Elinor were overseas for the first time and had been living in England less than a year. Ezra Pound had "dis covered" Frost and was touting his work all over London. The poems Frost brought to England stashed away in his trunk were accepted by David Nutt and published as A Boy's Will in April. At thirty-nine Frost had his first book. Just two months earlier, in February, the Armory Show had opened in New York. Amidst the Redons, Rodins and Ce zannes, the Matisses, Picassos and Picabias, one Hopper was mounted. It would be hard to imagine a starker contrast to the works which caused such a furor. Nonetheless, "Sailing" was purchased for $250. "Nude Descending a Staircase" brought barely a hundred dollars more. At thirty one Edward Hopper had sold his first oil. It would be ten years before he sold another. -

Pardo Garcia2020.Pdf (13.56Mb)

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Hopper beyond the commonplace EDWARD HOPPER BEYOND THE COMMONPLACE. A review of his work under the light of Walter Benjamin´s concept of poverty of experience. Ana Pardo García 1 Hopper beyond the commonplace Abstract The title of this dissertation —Edward Hopper beyond the commonplace— alludes to the fact that, although the work of Edward Hopper is widely acknowledged in the history of the twentieth century art, critical literature focused on it has resorted to a number of labels (Americanness, alienation, loneliness and the like) which, over time, have become clichés with very little critical insight and with very weak theoretical and visual foundations. My first aim is, therefore, to develop a different critical framework which is up to the task of analysing the indisputable visual relevance of Hopper’s work. -

Jutlandic Days E-Shop Selected by Asbjorn

Edward Hopper. Shop in the shop in my E-shop. Print on demand by Art.com Side 1 af 3 Jutlandic Days e-shop Selected by Asbjorn Lonvig Edward Hopper shop in the shop This store brought to you by Nighthawks Lighthouse at Two Lights Early Sunday Morning, Edward Hopper Rooms By the Sea 1930 New York Movie Edward Hopper Buy From Art.com Edward Hopper Edward Hopper Edward Hopper Buy From Art.com Buy From Art.com Buy From Art.com Buy From Art.com Room in New York Chop Suey Cape Cod Evening Approaching a city, 1946 Gas, 1940 Edward Hopper Edward Hopper Edward Hopper Edward Hopper Edward Hopper Buy From Art.com Buy From Art.com Buy From Art.com Buy From Art.com Buy From Art.com The Martha McKean of Lighthouse & The Sheridan Theatre, Summer Evening Wellfleet, 1944 Route 6, Eastham Buildings,Portland 1928 Edward Hopper Edward Hopper Edward Hopper Edward Hopper Edward Hopper Buy From Art.com Buy From Art.com Buy From Art.com Buy From Art.com Buy From Art.com House By the Railroad, Summertime Ground Swell, 1940 The Lee Shore 1925 Edward Hopper Edward Hopper Edward Hopper Edward Hopper Woman At Table Buy From Art.com Buy From Art.com Buy From Art.com Buy From Art.com Edward Hopper Buy From Art.com Martha McKean of The Long Leg Dawn in Pennsylvania Approaching a City Second Story Sunlight Wellfleet Edward Hopper Edward Hopper Edward Hopper Edward Hopper Edward Hopper Buy From Art.com Buy From Art.com Buy From Art.com Buy From Art.com Buy From Art.com This store brought to you by Ground Swell New York Office Drug Store New York Restaurant Edward Hopper Room In Brooklyn Edward Hopper Edward Hopper Edward Hopper Buy From Art.com Edward Hopper Buy From Art.com Buy From Art.com Buy From Art.com Buy From Art.com Ground Swell Hills, South Truro First Row Orchestra, 1951 Seven A. -

EDWARD HOPPER in CRITICAL CONDITION by JAMES BARRY

EDWARD HOPPER IN CRITICAL CONDITION by JAMES BARRY BLEDSOE M.A., University of British Columbia, 1974 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Anthropology and Sociology We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA June, 1974 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that; the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department: or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of A«rfk fbp^l^'-j <=Pn£ Socjo/o^^ The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada Date August lj 1974 Abstract This thesis is about the relationship between an artist and his critics. It explores how critics develop ways of interpreting a painter's work which be• come established as the meaning of his paintings. Edward Hopper's paintings are basically ambiguous. They can be de• ciphered in a number of ways depending upon what set of interpretive procedures are used to unlock them. Therefore any consistency in the written description of his work can be looked upon as a perceived accomplishment of the critics. We have been taught how to interpret Hopper through the professional written analysis of the art critic or art historian. -

Tate Papers - Edward Hopper and British Artists

Tate Papers - Edward Hopper and British Artists http://www.tate.org.uk/research/tateresearch/tatepapers/06autumn/frase... ISSN 1753-9854 TATE’S ONLINE RESEARCH JOURNAL Edward Hopper and British Artists David Fraser Jenkins Fig.1 Edward Hopper Stairway at 48 rue de Lille, Paris 1906 Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Josephine N. Hopper Bequest 70.1295 © Whitney Museum of American Art, New York enlarge Edward Hopper arrived in Paris for the first time in October 1906, coincidentally a day after Cézanne died in the south of France. He remembered seeing some of the French master's paintings at the autumn Salon that year, but took nothing from his painting, then or later, and it was partly as a result of keeping this distance that he used to be portrayed as an outsider from modernism.1 But in this stance Hopper is comparable to some British artists of his time, all of whom moved away independently from Impressionism along a different avenue from the one taken by the beneficiaries of Cézanne. The possession of painterly skill may not be a necessary condition to becoming an outstanding painter in oils, but when it happens to be there, it certainly counts. Hopper's natural talent for painting remains astonishing, and was evident early in his career, in the small sketch on panel that he made of the stairwell of the Baptist lodging house in the rue de Lille in Paris, where he lived for the eight months of his visit to France in 1906-7 (fig.1).2 It seems an unassuming little painting at first glance, but as a technical exercise in the control of colour tones and the depiction of space it is ambitious, and a tour de force.