Tate Papers - Edward Hopper and British Artists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PART IV CATALOGUES of Exhibitions,734 Sales,735 and Bibliographies

972 “William Blake and His Circle” PART IV CATALOGUES of Exhibitions,734 Sales,735 and Bibliographies 1780 The Exhibition of the Royal Academy, M.DCC.LXXX. The Twelfth (1780) <BB> B. Anon. "Catalogue of Paintings Exhibited at the Rooms of the Royal Academy", Library of the Fine Arts, III (1832), 345-358 (1780) <Toronto>. In 1780, the Blake entry is reported as "W Blake.--315. Death of Earl Goodwin" (p. 353). REVIEW Candid [i.e., George Cumberland], Morning Chronicle and London Advertiser, 27 May 1780 (includes a criticism of “the death of earl Goodwin, by Mr. Blake”) <BB #1336> 734 Some exhibitions apparently were not accompanied by catalogues and are known only through press-notices of them. 735 See G.E. Bentley, Jr, Sale Catalogues of Blake’s Works 1791-2013 put online on 21 Aug 2013 [http://library.vicu.utoronto.ca/collections/special collections/bentley blake collection/in]. It includes sales of contemporary copies of Blake’s books and manuscripts, his watercolours and drawings, and books (including his separate prints) with commercial engravings. After 2012, I do not report sale catalogues which offer unremarkable copies of books with Blake's commercial engravings or Blake's separate commercial prints. 972 973 “William Blake and His Circle” 1784 The Exhibition of the Royal Academy, M.DCC.LXXXIV. The Sixteenth (London: Printed by T. Cadell, Printer to the Royal Academy) <BB> Blake exhibited “A breach in a city, the morning after a battle” and “War unchained by an angel, Fire, Pestilence, and Famine following”. REVIEW referring to Blake Anon., "The Exhibition. Sculpture and Drawing", Morning Chronicle and London Advertiser, Thursday 27 May 1784, p. -

The Hopperville Express

Curriculum Units by Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute 1989 Volume V: America as Myth The HopperVille Express Curriculum Unit 89.05.01 by Casey Cassidy This curriculum unit is designed to utilize Edward Hopper’s realistic 20th century paintings as a “vehicle” to transport middle school children from the hills and seasides of New England, through the metropolis of New York City, and across the plains of the western United States. As our unit continues along its journey, it will cross a timeline of approximately forty years which will serve to highlight technological improvements in transportation, changes in period attire, and various architectural styles. We will experience a sense of nostalgia as we view a growing spirit of nationalistic pride as we watch America grow, change, and move forward through the eyes of Edward Hopper. The strategies in this unit will encourage the youngsters to use various skills for learning. Each student will have the opportunity to read, to critically examine slides and lithographs of selected Hopper creations, to fully participate in teacherled discussions of these works of art, and to participate first hand as a commercial artist—i.e. they will be afforded an opportunity to go out into their community, traveling on foot or by car (as Edward Hopper did on countless occasions), to photograph or to sketch buildings, scenes, or structures similar to commonplace areas that Hopper painted himself. In this way, we hope to create a sense of the challenge facing every artist as they themselves seek to create their own masterpieces. Hopper was able “to portray the commonplace and make the ordinary poetic.”1 We hope our students will be able to understand these skills and to become familiar with the decisions, the inconveniences, and the obstacles of every artist as they ply their trade. -

Edward Hopper, Landscape, and Literature

Edward Hopper, Landscape, and Literature Gail LEVIN The art of Edward Hopper, the American realist painter, contains many clues that allow us to trace his interest in literature, which in turn helps to characterize his particular brand of realism. 1) Signs of Hopper’s engagement with literature emerge already in his boyhood. Born in 1882, Hopper grew up in Nyack, New York, a town on the Hudson River, some forty miles north of New York City, where he went to attend art school and lived as an adult, until his death in 1967, shortly before his eighty-fifth birthday. Among the early indications that literature affected Hopper is a plaque that he designed for a Boys’ Yacht Club, which he formed together with three pals. Hopper designed this plaque with the names of the members’ boats. While the other boys chose female names that were upbeat and innocuous, Edward’s choice, Water Witch (Fig. 1), telegraphs an effect of reading on his imagination. He took the name for his boat from The Water- Witch, James Fenimore Cooper’s 1830 novel that tells how the “exploits, mysterious character, and daring of the Water-Witch, and of him who sailed her, were in that day, the frequent subjects of anger, admiration and surprise.... ” 2) His boyhood interest led Hopper to build not only a sailboat but a canoe. Later he would remark, “I thought at one time I’d like to be a naval architect because I am interested in boats, but I got to be a Fig. 1: Edward Hopper, Water Witch on painter instead.” 3) His interest in nautical life sign, Private Collection. -

R.B. Kitaj Papers, 1950-2007 (Bulk 1965-2006)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3q2nf0wf No online items Finding Aid for the R.B. Kitaj papers, 1950-2007 (bulk 1965-2006) Processed by Tim Holland, 2006; Norma Williamson, 2011; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Manuscripts Division Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ © 2011 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the R.B. Kitaj 1741 1 papers, 1950-2007 (bulk 1965-2006) Descriptive Summary Title: R.B. Kitaj papers Date (inclusive): 1950-2007 (bulk 1965-2006) Collection number: 1741 Creator: Kitaj, R.B. Extent: 160 boxes (80 linear ft.)85 oversized boxes Abstract: R.B. Kitaj was an influential and controversial American artist who lived in London for much of his life. He is the creator of many major works including; The Ohio Gang (1964), The Autumn of Central Paris (after Walter Benjamin) 1972-3; If Not, Not (1975-76) and Cecil Court, London W.C.2. (The Refugees) (1983-4). Throughout his artistic career, Kitaj drew inspiration from history, literature and his personal life. His circle of friends included philosophers, writers, poets, filmmakers, and other artists, many of whom he painted. Kitaj also received a number of honorary doctorates and awards including the Golden Lion for Painting at the XLVI Venice Biennale (1995). He was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters (1982) and the Royal Academy of Arts (1985). -

The Unification of London

THE RT. HON. G. J. GOSCHEN, M.P., SAYS CHAOS AREA A OF _o_ AND _)w»___x_;_»wH RATES, OF «-uCA__, AUTHORITIES, OF. fa. f<i<fn-r/r f(£sKnyca __"OUR REMEDIEsI OFT WITHIN OURSELVES DO LIE." THE UNIFICATION OF LONDON: THE NEED AND THE REMEDY. BY JOHN LEIGHTON, F.S.A. ' LOCAL SELF-GOVERNMENT IS A CHAOS OF AUTHORITIES,OF RATES, — and of areas." G. jf. Goscheu London: ELLIOT STOCK, 62, PATERNOSTER ROW, CITY 1895. To The Right Hon. SIR JOHN LUBBOCK, P.C., M.P., HON. LL.D. (CAMB., EDIN., AND DUB.), F.R.S., F.S.A., F.G.S., M.R.I., V.P.E.S., Trustee of the British Museum,Commissioner of Lieutenancy for London, THIS BOOK is dedicated by CONTENTS. PAGE Chapter — I.— The Need 7 II. The Remedy ... — ... n III.— Local Government ... 17 IV. Conclusion 23 INDEX PAGE PAGE Abattoirs ... 21 Champion Hill 52 Address Card 64 Chelsea ... ... ... 56 Aldermen iS City 26 Aldermen, of Court ... 19 Clapham ... ... ... 54 AsylumsBoard ig Clapton 42 Clerkenwell 26 Barnsbury ... ... ... 29 Clissold Park 4U Battersea ... ... ... 54 Coroner's Court 21 Battersea Park 56 County Council . ... 18 Bayswater 58 County Court ... ... 21 Bermondsey 32 BethnalGreen 30 Bloomsbury 38 Dalston ... ... ... 42 Borough 34 Deptford 48 Borough Council 20 Dulwich 52 Bow 44 Brixton 52 Finsbury Park 40 Bromley ... 46 Fulham 56 Cab Fares ... ... ... 14 Gospel Oak 02 Camberwell 52 Green Park Camden Town 3S Greenwich ... Canonbury 28 Guardians, ... Board of ... 20 PAGE PAGE Hackney ... ... ... 42 Omnibus Routes ... ... 15 Hampstead... ... ... Co Hatcham ... 50 Paddington 58 Haverstock Hill .. -

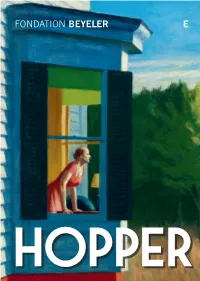

Room Guide Edward Hopper

FONDATION BEYELER E EDWARD HOPPER INTRODUCTION 26 January – 17 May 2020 Edward Hopper (1882–1967) is one of the great familiar yet ultimately little known exponents of modern art. Some of his works have become exceptionally popular and belong to the cultural memory of our age. Yet some aspects of his work are known only to a few specialists. Many of his paintings, as well as his watercolors and drawings, thus remain to be discovered. Our exhibition makes an important contribution in this respect. For the first time, it brings together Hopper’s landscapes, including urban landscapes, providing visitors with deep insights into the artist’s external and internal worlds. Renowned filmmaker Wim Wenders, a long-time, self-avowed Hopper fan, has created a personal tribute to Cover: Edward Hopper the artist, the 3D film Two or Three Things I Know about Cape Cod Morning, 1950 (detail) Edward Hopper, specially for the exhibition at the Oil on canvas, 86.7 x 102.3 cm Smithsonian American Art Museum Fondation Beyeler. Starting with motifs from Hopper’s © Heirs of Josephine Hopper / 2020 ProLitteris, Zurich. pictures, he revives the artist’s characteristic melancholy Photo: Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gene Young mood. The film is screened in the last room of the exhibition. We hope you enjoy the exhibition and would be delighted for you to share your experience with others. ROOM 1 ROOM 2 1 2 Railroad Sunset, 1929 Square Rock, Ogunquit, 1914 Railroad Sunset shows the passage from day into night, Like Edward Hopper’s other landscape paintings, this an evening sky displaying striking light and color mood. -

Winning Smiles

THE MAGAZINE FOR PEABODY RESIDENTS AUTUMN 2015 Prize fruit and veg at Cumberland Market’s annual Winning smiles show ENGAGE Winning veg from Cumberland Market AUTUMN 2015 From December 2015, Engage A word from Steve Howlett magazine will be replaced by elcome to your an email newsletter. autumn issue of Engage. I’m very Editor: Kirsten Edwards W partial to home grown veg, Design: Camille Neilson and I’m very impressed by the Photography: Paul Sanders; allotment holders at Cumberland David Boucher; shutterstock.com; Market, who grow everything Jody Kingzett from peaches to courgettes. You can see photos of their amazing Address all content suggestions, produce above and on p8. contest entries or comments to: This will be our last full for checking out the Peabody Editor, Engage, Peabody, printed issue of Engage so, if newsletter and browsing our 45 Westminster Bridge Road, you haven’t yet signed up to our website. See p10 to find out London SE1 7JB email newsletter, turn to p14 to about just some of the features Email: [email protected] find out how to do it. Everyone you can find online. who subscribes will be in with © Peabody 2015 the chance to win one of three Amazon Fire tablets – perfect Peabody Direct: 020 7021 4444 or 0800 022 4040 (free from BT landlines) In this issue Email: [email protected] 03 News 15 How are we doing? Residents of Cumberland Market, 08 Grow your own Performance information Millbank, Victoria Park and Lee Green Cumberland Market held its 77th 16 Your money can also call 020 7255 4100. -

With His Art and Legacies Edward Hopper

Güzel Sanatlar Fakültesi Dergisi, 2020, Cilt 2, Sayı 2, 173-184 WITH HIS ART AND LEGACIES EDWARD HOPPER Ufuk ÇETİN1 Abstract The works of Edward Hopper, one of the most important artists of America in the 20th century, are universal. Its impressive content is emotionally explained to the lives at the contemporary audience. He illustrates moments and more significantly, characters nearly every viewer can instantly know. There is no ambiguity inside Hopper’s works in a visual cultural way. He impacted lots of artists, photographers, filmmakers, set designers, dancers, writers, and his effect has touched many artists like Rothko, Segal and Oursler, who work with different mediums. He is an interesting artist in the way of impressing nearly all photographers from Arbus to Eggleston. Including Mendes, Lynch and Welles, generations have been inspired from Hopper’s dramatic viewpoints, lighting, and moods. His painting, “Residence by the Railroad” (1925) stimulated Alfred Hitchcock’s house in Psycho (1960) as well as that in Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven (1978). This article introduces the artist with some examples of his personality and samples from his works. Hopper’s paintings are attractive to some writers and musicians. For instance, Tom Waits made an album known as “Nighthawks on the Diner”. Also, Madonna selected a name for a live performance tour after Hooper’s “Girlie Display”. Keywords: Painting, Edward Hopper, American art, landscape painting, visual culture. 1 Öğr. Gör. Dr. Tekirdağ Namık Kemal Üniversitesi, Çorlu Mühendislik Fakültesi, Bilgisayar Mühendisliği Bölümü, [email protected], https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5102-8183 174 Ufuk ÇETİN Sanatı ve Efsaneleriyle Edward Hopper Özet Amerika’nın 20. -

Out of Hours Art

Out of Hours Art Living tHe dreAm The Scottish Colourists Series: JD Fergusson 7 December 2013 – 15 June 2014 Scottish National Gallery Of Modern Art (Modern Two) 73 Belford Road, Edinburgh EH4 3DS In Midnight in Paris, Woody Allen transports his leading character back to the Paris of La Belle Epoque, the glorious period at the start of the 20th century when the French capital was the centre of artistic freedom. Just over a century ago, a young Scottish medical student similarly transported himself to live in that fantastic, creative melting pot. John Duncan Fergusson spent 2 years at Edinburgh University before giving up his medical studies to become a painter, initially visiting France in summers when he stayed as long as he could afford, but in 1905 he moved permanently, abandoning family and convention, to live the rest of his J. d. Fergusson (1874–1961). Summer 1914, 1934. Oil on canvas 88 x 113.5 cm. the Fergusson gallery, Perth life, a self-taught painter, ‘trying for truth, & Kinross Council — presented by the Jd Fergusson Art Foundation 1991. for reality, through light’. He was often very poor, but he never wonder S.J. (Peploe, Fergusson’s fellow is perhaps still more famous than her borrowed money; he lived on porridge Scottish Colourist) said these were some partner. for lunch, and onion and potato soup for of the greatest nights of his life. They Fergusson returned to Paris after the dinner, with an occasional night out when were the greatest nights in anyone’s life Great War, but in 1939, they both relocated he met his friends at a cheap restaurant — Scheherezade, Petruschka, Sacre du to Glasgow for their final move. -

Edward Hopper's Adaptation of the American Sublime

Rhetoric and Redress: Edward Hopper‘s Adaptation of the American Sublime A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Fine Arts Rachael M. Crouch August 2007 This thesis titled Rhetoric and Redress: Edward Hopper’s Adaptation of the American Sublime by RACHAEL M. CROUCH has been approved for the School of Art and the College of Fine Arts by Jeannette Klein Assistant Professor of Art History Charles A. McWeeny Dean, College of Fine Arts Abstract CROUCH, RACHAEL M., M.F.A., August 2007, Art History Rhetoric and Redress: Hopper’s Adaptation of the American Sublime (80 pp.) Director of Thesis: Jeannette Klein The primary objective of this thesis is to introduce a new form of visual rhetoric called the “urban sublime.” The author identifies certain elements in the work of Edward Hopper that suggest a connection to earlier American landscape paintings, the pictorial conventions of which locate them within the discursive formation of the American Sublime. Further, the widespread and persistent recognition of Hopper’s images as unmistakably American, links them to the earlier landscapes on the basis of national identity construction. The thesis is comprised of four parts: First, the definitional and methodological assumptions of visual rhetoric will be addressed; part two includes an extensive discussion of the sublime and its discursive appropriation. Part three focuses on the American Sublime and its formative role in the construction of -

Regent's Park Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Strategy

Regent’s Park Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Strategy Adopted 11 July 2011 Contents Part 1 Regent’s Park Conservation Area Appraisal Page 1 Introduction 4 2 Definition of special character 5 3 Planning Policy context 6 National – London Borough of Camden – local – Crown Estates 4 Assessing special interest 4.1 Location and setting – city borough and local 11 4.2 Character and plan form 12 4.3 Landscape and topography 13 4.4 Historic development and archaeology 14 4.5 Spatial analysis 17 4.6 Key views 18 4.7 Character zones 19 4.8 Land use activity and influence of uses 23 4.9 The quality of buildings and their contribution to the area 24 4.10 Local details 34 4.11 Prevalent local and traditional materials and the public realm 35 4.12 The contribution of green spaces 36 4.13 Audit of heritage assets 37 o Listed buildings o Positive o Neutral o Negative 4.14 Buildings at Risk 42 5 Problems, pressures and capacity for change 43 6 Community involvement 44 7 Boundary Review 45 8 Summary of issues 47 1 Part 2 Regent’s Park Management Strategy Page 1 Introduction 1.1 Background 49 1.2 Policy and legislation 50 2 Monitoring and review 52 3 Maintaining character 55 4 Recommendations for action 57 5 Boundary changes 58 6 Current issues 6.1 Summary 59 6.2 Maintaining special character 59 6.3 Enhancement schemes for the public realm 60 6.4 Economic and regeneration strategy 61 7 Management of change - Application of policy guidance 7.1 Quality of Applications 62 7.2 Guidance 62 7.3 Enforcement strategy 67 7.4 Article 4 Directions 68 7.5 -

International

International International View | Lyon & Turnbull Autumn/Winter 2019 LIKE NOWHERE RCStweets RCSocial RCSocial ELSE RCSocial rcs.ac.uk RCSocial Corporate LNE ad.indd 1 23/08/2019 11:45:47 International CONTENTS 5 Top Lots 10 Past Events & Cultural Affairs 12 Announcements 20 Feature Stories 18 Phillip Bruno | An Adopted Scotsman 20 A Grand Old Flag | The Stars & Stripes Collection of Dr. Peter J. Keim 24 In Perfect Bloom | Dutch Still Life 26 Darwin’s Magnum Opus 28 The Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Richard E. Oldenburg 30 An Artistic Haven | St Ives 32 Looking Back | Berthe Morisot 34 Sunshine Stones | Yellow Sapphires 36 When Meissen Went Modern | Henry van de Velde 38 In the Forefront of the Movement | The Art of Isabel Codrington 40 Ancient Cyprus | At the Crossroads 42 A Vision of Eden | Daniel Garber's By The River 44 Through the Embroiderer’s Eye | May Morris Textiles 46 I Hope for Nothing but Vengeance | Autograph Letters from Comte d’Artois 48 The Macallan Millennium 49 Ding Ware Porcelain | A Thousand Years of Elegance 50 The Collection of Stephanie Eglin | Opulence & Optimism 52 Capturing Coastal Life | Sam Bough 54 Clement Hungerford Pollen | An English Gentleman in the Great North American West 56 Inspirations | Celebrating Women in Ceramics 58 The Collection of Robert J. Morrison 62 Noteworthy 76 Beyond the Auction House 76 Renewal | Forging the Future in Silver 78 Spotlight | Philadelphia Museum of Art Contemporary Craft Show 82 Marchmont House | A Home for Makers & Creators 85 Contact Us 88 Auction Calendar CREDITS EDITORS-IN-CHIEF Whitney Bounty Alex Dove ASSISTANT EDITOR Madeline Hill GRAPHIC DESIGN Whitney Bounty PHOTOGRAPHY Ryan Buckwalter Thomas Clark Helen Jones James Robertson Alex Robson James Stone PUBLISHERS Alex Dove Thomas B.