Mexico Before the Election Storm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mexico City Committee History of Exchanges

History of Exchange Mexico City, Mexico Chicago’s Sister City Since 1991 Co-Chair: Alejandro Silva Co-Chair: Adriana Escarcega 1991 Focus: Signing Agreement Chicago and Mexico City became friendship cities in October 1991, when Mayor Richard M. Daley and Mexico City Mayor Manuel Camacho Solis signed a Friendship Cities Agreement at a reception hosted by the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. While in Chicago, Mayor Solis addressed the University of Chicago's Mexican Studies Department, visited the Mexican Fine Arts Center Museum and the Chicago Council on Foreign Relations and toured Chicago's Mexican communities. Prior to the signing, Mexico City officials Hesiquio Aguilar and Xavier Casillas participated in the 1991 Sister Cities International Conference held in July. 1992 Focus: Culture Helen Valdez, Chair of the Mexico City Committee, presented slides and information on the Archaeological Treasures of Tenochitian exhibit. Focus: Culture Chicago poets participated in the Poem for Mexico City contest where the prize for the winner was a trip to Mexico City and the opportunity to perform. Poets from Mexico City, Prague and Shenyang attended the finals. 1993 Focus: Culture The Mexico City Committee sponsored The Art of the Other Mexico: Sources and Meanings. This exhibit, produced by the Mexican Fine Arts Center Museum opened in November 1993 and featured contemporary artwork of 20 artists of Mexican descent from across the U.S. Focus: Culture Artist Monica Castillo participated in the O'Hare International Airport Terminal mural project. The mural representing Ms. Castillo's impression of Chicago, titled El Viento (The Wind), was permanently installed in the arrival corridor of the International Terminal at O'Hare Airport. -

Acusa Padierna a Rosario Robles 02 De Agosto Del 2011 00:59:00 CST Notimex

MARTES 02 DE AGOSTO 2011 DIARIO 8 COLUMNAS Acusa Padierna a Rosario Robles 02 de Agosto del 2011 00:59:00 CST Notimex *De provocar la crisis al interior del PRD. La secretaria general perredista, Dolores Padierna, acusó a Rosario Robles Berlanga de ser la causante de la crisis económica que enfrenta el PRD y de haber vendido información a adversarios políticos para debilitar la fuerza de ese instituto político. En entrevista sostuvo que ocho años después de la gestión de Robles, el Partido de la Revolución Democrática (PRD) aún no logra reponerse del daño económico y político que le hizo. ’No creo que Rosario Robles pueda dormir tranquila ni después de muerta, porque el daño que le ha hecho a nuestro partido es monumental, todavía no se acaba lo financiero, menos lo político”, sostuvo la actual dirigente perredista. Como parte de esa afectación señaló la relación “perversa” que Robles Berlanga sostuvo con el empresario de origen argentino Carlos Ahumada, pues además de utilizar recursos del partido para hacer negocios con él, le dio todo el poder para estar presente hasta en las decisiones del Comité Ejecutivo Nacional. “Rosario tomó recursos del partido para hacer negocios con una persona sin escrúpulos, esa fue la relación fugaz de ese personaje en estas oficinas. Hemos visto fotografías en las que hasta estaba en reuniones del propio Comité Ejecutivo Nacional, entraba hasta la cocina y esto era por la relación personal y de negocios que tenía Rosario Robles con esa persona”, mencionó. Padierna Luna aseveró que Robles Berlanga no sólo pervirtió y corrompió al PRD, sino que ella como presidenta vendió información a los adversarios del partido del sol azteca como ’a Carlos Salinas de Gortari y a Diego Fernández de Cevallos’. -

Controversial Ex-Mayor of Mexico City Marcelo Ebrard Seeks Seat in Congress Carlos Navarro

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository SourceMex Latin America Digital Beat (LADB) 4-1-2015 Controversial Ex-Mayor of Mexico City Marcelo Ebrard Seeks Seat in Congress Carlos Navarro Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sourcemex Recommended Citation Navarro, Carlos. "Controversial Ex-Mayor of Mexico City Marcelo Ebrard Seeks Seat in Congress." (2015). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sourcemex/6153 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Latin America Digital Beat (LADB) at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in SourceMex by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LADB Article Id: 79608 ISSN: 1054-8890 Controversial Ex-Mayor of Mexico City Marcelo Ebrard Seeks Seat in Congress by Carlos Navarro Category/Department: Mexico Published: 2015-04-01 The presidential elections in Mexico are still more than three years away, but there is already some speculation on which party and candidate is going to carry the banner for the left. As of now, the consensus is that Andrés Manuel López Obrador will return for a third run at the presidency in the 2018 elections, representing the Movimiento Regeneración Nacional (Morena) and perhaps a broader leftist coalition. López Obrador’s path is far from defined, however, as the upcoming midterm elections on June 7 will go a long way to determine whether the Partido de la Revolución Democrática (PRD) or the upstart Morena will be a stronger party not only in the federal Congress but also in the legislatures of several states. -

Mexico: Freedom in the World 2021 Country Report | Freedom Hous

FREEDOM IN THE WORLD 2021 Mexico 61 PARTLY FREE /100 Political Rights 27 /40 Civil Liberties 34 /60 LAST YEAR'S SCORE & STATUS 62 /100 Partly Free Global freedom statuses are calculated on a weighted scale. See the methodology. Overview Mexico has been an electoral democracy since 2000, and alternation in power between parties is routine at both the federal and state levels. However, the country suffers from severe rule of law deficits that limit full citizen enjoyment of political rights and civil liberties. Violence perpetrated by organized criminals, corruption among government officials, human rights abuses by both state and nonstate actors, and rampant impunity are among the most visible of Mexico’s many governance challenges. Key Developments in 2020 • With over 125,000 deaths and 1.4 million cases, people in Mexico were severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. The government initially hid the virus’s true toll from the public, and the actual numbers of cases and deaths caused by the coronavirus are unknown. • In July, authorities identified the bone fragments of one of the 43 missing Guerrero students, further undermining stories about the controversial case told by the Peña Nieto administration. • Also in July, former head of the state oil company PEMEX Emilio Lozoya was implicated in several multimillion-dollar graft schemes involving other high- ranking former officials. Extradited from Spain, he testified against his former bosses and peers, including former presidents Calderón and Peña Nieto. • In December, the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) named Mexico the most dangerous country in the world for members of the media. -

Los Suspirantes 2024 060921

1 www.enkoll.com | (55) 8500 7777 | 06 de septiembre, 2021 06 / 09 / 2021 SUSPIRANTES 2024 INTENCIÓN DE VOTO PARA PRESIDENTE 2024 Aunque aún falta tiempo, si hoy fueran las elecciones para elegir al Presidente de México, ¿por cuál partido político votaría usted? PREFERENCIA BRUTA 39 14 10 10 12 4 3 3 2 2 1 Otros partidos Ninguno No sabe Otros partidos: sin especificar. 2 55 8500 7777 [email protected] www.enkoll.com 06 / 09 / 2021 SUSPIRANTES 2024 INTENCIÓN DE VOTO PARA PRESIDENTE 2024 Aunque aún falta tiempo, si hoy fueran las elecciones para elegir al Presidente de México, ¿por cuál partido político votaría usted? PREFERENCIA EFECTIVA 50 18 13 5 4 4 3 3 3 55 8500 7777 [email protected] www.enkoll.com 06 / 09 / 2021 SUSPIRANTES 2024 CONOCIMIENTO DE PRESIDENCIABLES A continuación, le mencionaré el nombre de algunos personajes políticos, por favor dígame si los conoce o ha escuchado hablar de ellos Sí lo conoce No lo conoce Ricardo Anaya Cortés 86 14 Alfonso Durazo Montaño 49 51 Margarita Zavala 83 17 Esteban Moctezuma Barragán 47 53 Marcelo Ebrard Casaubón 83 17 Javier Corral 41 59 Claudia Sheinbaum Pardo 79 21 Alejandro Murat Hinojosa 40 60 Alfredo del Mazo Maza 75 25 Juan Ramón de la Fuente 36 64 Miguel Ángel Osorio Chong 74 26 Alejandro Moreno Cárdenas “Alito” 35 65 Luis Donaldo Colosio Riojas 73 27 Enrique Alfaro Ramírez 31 69 Tatiana Clouthier Carrillo 57 43 Marko Cortés 31 69 Ricardo Monreal Ávila 53 47 Rocío Nahle García 26 74 Samuel García Sepúlveda 51 49 Mauricio Vila Dosal 22 78 Lázaro Cárdenas Batel 49 51 Francisco Domínguez -

Morena En El Sistema De Partidos En México: 2012-2018

Morena en el sistema de partidos en México: 2012-2018 Morena en el sistema de partidos en México: 2012-2018 Juan Pablo Navarrete Vela Toluca, México • 2019 JL1298. M68 Navarrete Vela, Juan Pablo N321 Morena en el sistema de partidos en México: 2012-2018 / Juan Pablo 2019 Navarrete Vela. — Toluca, México : Instituto Electoral del Estado de México, Centro de Formación y Documentación Electoral, 2019. XXXV, 373 p. : tablas. — (Serie Investigaciones Jurídicas y Político- Electorales). ISBN 978-607-9496-73-9 1. Partido Morena - Partido Político 2. Sistemas de partidos - México 3. López Obrador, Andrés Manuel 4. Movimiento Regeneración Nacional (México) 5. Partidos Políticos - México - Historia Esta investigación, para ser publicada, fue arbitrada y avalada por el sistema de pares académicos en la modalidad de doble ciego. Serie: Investigaciones Jurídicas y Político-Electorales. Primera edición, octubre de 2019. D. R. © Juan Pablo Navarrete Vela, 2019. D. R. © Instituto Electoral del Estado de México, 2019. Paseo Tollocan núm. 944, col. Santa Ana Tlapaltitlán, Toluca, México, C. P. 50160. www.ieem.org.mx Derechos reservados conforme a la ley ISBN 978-607-9496-73-9 ISBN de la versión electrónica 978-607-9496-71-5 Los juicios y las afirmaciones expresados en este documento son responsabilidad del autor, y el Instituto Electoral del Estado de México no los comparte necesariamente. Impreso en México. Publicación de distribución gratuita. Recepción de colaboraciones en [email protected] y [email protected] INSTITUTO ELECTORAL DEL ESTADO -

Presentación De Powerpoint

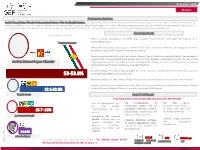

ELECTION 2018 RESULTS PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION Andrés Manuel López Obrador is the projected winner of the Presidential election. This situation would respond to a candidate that was able to capitalize on the high social discontent and an 18 year political effort. The AMLO effect is reflected at the national level, since the Coalition that he leads will obtain different strategic positions, such as the Head of Government of Mexico City, at least 3 governorships, first minority in the Federal Congress, among other local posts. This electoral process will result in a substantial change in the national political order. CONSIDERATIONS ESTIMATED PERCENTAGES With a historical participation rate (63% approx.), Mexico demonstrates once again the maturity of its Projected winner electoral democracy. AMLO will have broad citizen support, however it will face a scenario in which half of the population voted for another option, which implies a significant challenge. The post-electoral declarations of José Antonio Meade, Ricardo Anaya and Jaime Rodríguez; the messages of support from various political personalities and from the Business Coordinating Council; as well as the Andrés Manuel López Obrador congratulations of leaders of other nations, including Donald Trump; are elements that provide certainty to the transition period when projecting a message of stability. President Enrique Peña Nieto acknowledged the results announced by the INE and committed to carry out 53-53.8% an efficient and orderly transition process. The traditional parties (PRI, PAN and PRD) will be forced to enter a period of self-criticism and reflection. Initially, markets show a favorable reaction. After the press conferences of José Antonio Meade, Ricardo 22.1-22.8% Anaya and Jaime Rodríguez Calderón the dollar is quoting at 19.86 pesos. -

Gender Parity Report.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 MIDDle EAST Middle East 114 Egypt 116 SUMMARY OF CORPORATE Israel** 118 GOVERNANCE CODes 8 Jordan 122 Tunisia 123 NORTH AMERICA Canada 20 AsIA United States** 22 China 126 Hong Kong 128 India* 132 LATIN AMERICA Indonesia 134 Argentina 30 Japan 140 Brazil 34 Philippines 144 Colombia 38 Singapore 148 Mexico 40 AUSTRALIA AND NeW ZEALAND AFRICA Australia 154 Morocco 46 New Zealand 156 South Africa 50 OUR OFFICes 159 EUROPe European Union 58 Austria* 64 Belgium 66 Denmark* 70 Finland* 74 France 78 Germany 82 Italy 86 Netherlands 92 Norway 94 Spain** 98 Sweden** 102 United Kingdom 106 * New for 2013 ** Updated for 2013 BREAKING THE GLASS CEILING: WOMEN IN THE BOARDROOM EXecutiVE SummaRY Paul Hastings is pleased to present the third edition of “Breaking the Glass Ceiling: Women in the Boardroom,” “For us it’s about talent… a comprehensive, global survey of the way different countries address the issue of gender parity on corporate boards. getting and keeping the This edition is a supplement to our full 2012 report, and provides updates to jurisdictions with notable developments over the past 12 months, as well as five new jurisdictions: Austria, Denmark, Finland, India, and Sweden. best talent. It’s about creating a culture where Given the dynamism and evolution of this issue, we have developed an interactive website dedicated to providing we can have innovative, the most current information and developments on the issue of diversity on corporate boards. Included are details about the legislative, regulatory, and private sector developments and trends impacting the representation of women creative solutions for on boards in countries around the world. -

25 De Agosto 2017

25 DE AGOSTO 2017 O C H O C O L U M N A S / P R I M E R A S P L A N A S “26 naciones unen esfuerzos” “Piden que fiscal anticorrupción no sea “cuate”” “Buscan alcaldes mejores gobiernos y tecnologías” “LLAMA FAYAD A LA HERMANDAD” “Llama Osorio Chong a replantear democracia” “Procurar igualdad, tarea de alcaldías” “EVALÚAN IMPACTO DE REFORMAS EN MÉXICO” “A derribar las barreras en América: Osorio y Fayad” “Destapan a Claudia Sheinbaum vía Twitter para CDMX” “Cimbra “encuesta” a Morena” “Morena irá con Sheinbaum” “Sheinbaum, la virtual candidata de Morena en CDMX” I N S T I T U C I O N A L Síntesis-Un reto, impulsar a las indígenas en política: IEEH: Ante la resistencia que se tiene en diferentes sectores de la sociedad, para el Instituto Estatal Electoral de Hidalgo aún es grande el reto para impulsar a las mujeres indígenas a la vida política, informó la consejera del IEEH, Martha Alicia Hernández Hernández. De acuerdo con la funcionaria electoral encargada de promover la participación política y empoderamiento de las mujeres , es lamentable que a la fecha persista un fuerte rechazo de manera global para que el sector femenino pueda ingresar en la toma de decisiones, y esto se complica aún más, si se trata del rubro indígena donde también hay usos y costumbres, la situación requiere de una doble labor. "Al igual que en otras entidades, en el estado hay comunidades donde los hombres son los encargados de la vida política, por ello la importancia de que se diera una cuota a través de la paridad de género, la cual en algunas regiones principalmente en las originarias, no se considera adecuado que deba ser aterrizada al sector femenino". -

Center-Left Morena Favored in Some Mexican Gubernatorial Elections in 2018 by Carlos Navarro Category/Department: Mexico Published: 2018-02-28

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository SourceMex Latin America Digital Beat (LADB) 2-28-2018 Center-Left orM ena Favored in Some Mexican Gubernatorial Elections in 2018 Carlos Navarro Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sourcemex Recommended Citation Navarro, Carlos. "Center-Left orM ena Favored in Some Mexican Gubernatorial Elections in 2018." (2018). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sourcemex/6415 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Latin America Digital Beat (LADB) at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in SourceMex by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LADB Article Id: 80533 ISSN: 1054-8890 Center-Left Morena Favored in Some Mexican Gubernatorial Elections in 2018 by Carlos Navarro Category/Department: Mexico Published: 2018-02-28 Presidential candidate Andrés Manuel López Obrador of the center-left Movimiento Regeneración Nacional (Morena) leads all the public opinion surveys that have been conducted to date, with the percentage of the lead depending on the individual poll. López Obrador’s standing in the polls is not surprising, because voters considered him the candidate most likely to stand up to US President Donald Trump’s anti-Mexico policies (SourceMex, Feb. 22, 2017). López Obrador has also seized on the growing resentment against the governing party, the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI), because of a string of corruption scandals involving the PRI (SourceMex, April 29, 2015, and April 19, 2017) and the party’s inability to curb seemingly out-of- control violence and insecurity (SourceMex, Dec. -

Freedom in the World Annual Report, 2019, Mexico

Mexico | Freedom House https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2019/mexico A. ELECTORAL PROCESS: 9 / 12 A1. Was the current head of government or other chief national authority elected through free and fair elections? 3 / 4 The president is elected to a six-year term and cannot be reelected. López Obrador of the left-leaning MORENA party won the July poll with a commanding 53 percent of the vote. His closest rival, Ricardo Anaya—the candidate of the National Action Party (PAN) as well as of the Democratic Revolution Party (PRD) and Citizens’ Movement (MC)—took 22 percent. The large margin of victory prevented a recurrence of the controversy that accompanied the 2006 elections, when López Obrador had prompted a political crisis by refusing to accept the narrow election victory of conservative Felipe Calderón. The results of the 2018 poll also represented a stark repudiation of the outgoing administration of President Peña Nieto and the PRI; the party’s candidate, José Antonio Meade, took just 16 percent of the vote. The election campaign was marked by violence and threats against candidates for state and local offices. Accusations of illicit campaign activities remained frequent at the state level, including during the 2018 gubernatorial election in Puebla, where the victory of PAN candidate Martha Érika Alonso—the wife of incumbent governor Rafael Moreno—was only confirmed in December, following a protracted process of recounts and appeals related to accusations of ballot manipulation. (Both Alonso and Moreno died in a helicopter crash later that month.) A2. Were the current national legislative representatives elected through free and fair elections? 3 / 4 Senators are elected for six-year terms through a mix of direct voting and proportional representation, with at least two parties represented in each state’s delegation. -

Presentación De Powerpoint

agosto 2020 Así van los 32 Gobernadores Encuesta nacional Presentamos con gusto los resultados de la última encuesta nacional sobre las condiciones de gobierno en México, realizada en las 32 entidades, elaborada por la casa encuestadora Arias Consultores y publicada en nuestro medio Revista32. Esperando que la información sea del agrado y satisfacción. Luis Octavio Arias Ortiz Director Arias Consultores 8331463600 móvil [email protected] El presente documento es propiedad de Arias Consultores, no se permite su publicación total o parcial salvo previa autorización expresa del propietario, en caso de referenciar los resultados presentados es necesario citar a la presente casa encuestadora. Ariasconsultores.com - www.facebook.com/ariasconsultores , Paseo de la Reforma 483 piso 14, Col. Cuauhtémoc, Del. Cuauhtémoc, [email protected] resumen Agosto 2020 Los recientes eventos del caso Lozoya generaron una alza en el incremento de aprobación del Presidente Andrés Manúel López Obrador y dicho incremento impacto directamente en la calificación de los gobernadores afines al presidente de México. Los gobernadores de MORENA y PES fueron los únicos que tuvieron un incremento en su promedio general de aprobación, siendo de +1.5%. El resto de gobernadores sufrieron descenso en su promedio general de aprobación. Los gobernadores del PRI perdieron -1.1% de aprobación, los del PAN -3.7% y los de MC+PRD e Independiente perdieron -10.3%. Considerando que la aprobación promedio de los gobernadores sigue en constante descenso pasando de 36.2% del mes anterior a 34.0% (-2.2%) se ratifica el impacto del presidente hacia sus gobernadores. A pesar del coronavirus, los estados enfatizan sus esfuerzos a el constante seguimiento de las actividades ordinarias de gobernabilidad.