Download the Dataset

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHAPTER II 1. Entry Summaries Page 2

1 CHAPTER I Table of Contents: CHAPTER II 1. Entry summaries Page 2 – 9 CHAPTER III 1. Abjata Khalif: Human trafficking Page10-12 2. Andualem Sisay: Ethiopia‘s crippled agriculture Page 13-15 3. Benjamin Tetteh: At mercy of the sea Page 16-18 4. Bibi-Aisha Wadualla: Religious bias in Egpy‘s universities Page 19-20 5. Deogratius Mmana: How dangerous criminals get out of jail before time to cause more havoc in public Page 21- 23 6. Kassim Mohamed: Pirates: Social bandits in Africa Page 24-27 7. Ken Opala: Lush Mrima Hill may be a death trap for unsuspecting residents Page 28-30 8. Khadija The Great Billion Dollar Drug Scam Page 31 - 35 9. Kipchumba Some: Police killings of youth Page 36-37 10. Muhyadin Ahmed Roble: What it Takes to Cover a Story in Somalia Page 38-40 11. Nicholas Ibekwe: Gowen and Bayero worked for Pfizer Page 41-43 12. Olu Jacob: The Muslim who risked all his Christian neighbours Page 44 -46 13. Patrick Mayoyo: Kenyan firms make killing from piracy Page 47 -48 14. Peter Nkanga: Last minute oil deals that cost Nigeria dear Page 49-52 15. Ramata Sore: Racist coverage of Africa in the US at the time of the World CupPage 53-55 16. Stephen Nartey: Ivorian girls trade sex for food Page 56 - 56 17. Tereza Ndanga: Cashing in on illegal abortions in Malawi Page 57 -58 18. Toyosi Ogunseye: Public school toilets, pits of the death and diseases Page 59 - 62 19. Estacio Valoi: Leaders complicit in the looting of wood in Zambezia Page 63 - 65 20. -

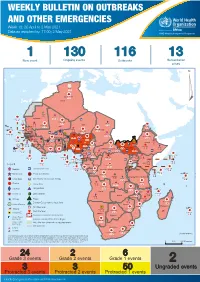

Weekly Bulletin on Outbreaks

WEEKLY BULLETIN ON OUTBREAKS AND OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 18: 26 April to 2 May 2021 Data as reported by: 17:00; 2 May 2021 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR Africa WHO Health Emergencies Programme 1 130 116 13 New event Ongoing events Outbreaks Humanitarian crises 64 0 122 522 3 270 Algeria ¤ 36 13 612 0 5 901 175 Mauritania 7 2 13 915 489 110 0 7 0 Niger 18 448 455 Mali 3 671 10 567 0 6 0 2 079 4 4 828 170 Eritrea Cape Verde 40 433 1 110 Chad Senegal 5 074 189 61 0 Gambia 27 0 3 0 24 368 224 1 069 5 Guinea-Bissau 847 17 7 0 Burkina Faso 236 49 258 384 3 726 0 165 167 2 063 Guinea 13 319 157 12 3 736 67 1 1 23 12 Benin 30 0 Nigeria 1 873 72 0 Ethiopia 540 2 556 5 6 188 15 Sierra Leone Togo 3 473 296 52 14 Ghana 70 607 1 064 6 411 88 Côte d'Ivoire 10 583 115 14 484 479 65 0 40 0 Liberia 17 0 South Sudan Central African Republic 1 029 2 49 0 97 17 25 0 22 333 268 46 150 287 92 683 779 Cameroon 7 0 28 676 137 843 20 3 1 160 422 2 763 655 2 91 0 123 12 6 1 488 6 4 057 79 13 010 7 694 112 Equatorial Guinea Uganda 1 0 542 8 Sao Tome and Principe 32 11 2 066 85 41 973 342 Kenya Legend 7 821 99 Gabon Congo 2 012 73 Rwanda Humanitarian crisis 2 310 35 25 253 337 Measles 23 075 139 Democratic Republic of the Congo 11 016 147 Burundi 4 046 6 Monkeypox Ebola virus disease Seychelles 29 965 768 235 0 420 29 United Republic of Tanzania Lassa fever Skin disease of unknown etiology 191 0 5 941 26 509 21 Cholera Yellow fever 63 1 6 257 229 26 993 602 cVDPV2 Dengue fever 91 693 1 253 Comoros Angola Malawi COVID-19 Leishmaniasis 34 096 1 148 862 0 3 840 146 Zambia 133 -

Post-Cairo Reproductive Health Policies and Programs: a Study of Five Francophone African Countries

The POLICY Project Justine Tantchou Ellen Wilson Post-Cairo Reproductive Health Policies and Programs: A Study of Five Francophone African Countries August 2000 Photo Credits All photos are printed with permission from the JHU/Center for Communication Programs. Post-CairoPost-Cairo ReproductiveReproductive HealthHealth PoliciesPolicies andand Programs:Programs: AA StudyStudy ofof FiveFive FrancophoneFrancophone AfricanAfrican CountriesCountries IntroductionIntroduction situation regarding reproductive health. In addition, given that all respondents are Since the ICPD in 1994, reproductive prominent in the reproductive health field, health has been a focus of health programs their perspectives actually influence the worldwide. Many countries have worked development of policies and programs in to revise reproductive health policy in their respective countries. accordance with the ICPD Programme of In each country, two to three members Action. In 1997, POLICY conducted case of the Reproductive Health Research studies in eight countries—Bangladesh, Committee—the country’s local branch of Ghana, India, Jamaica, Jordan, Nepal, RESAR—conducted the study. Research Peru, and Senegal—to examine field teams included at least one medical experiences in developing and specialist and one social science specialist. implementing reproductive health policies. The team carried out the fieldwork for the In 1998, RESAR conducted similar case case studies between October and studies in five Francophone African countries—Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, and Mali. RESAR’s purpose in conducting the studies was not to provide quantitative measurements of reproductive health indicators or an exhaustive inventory of reproductive health laws and policies but to improve understanding of reproductive health policy formulation and implementation. The study was qualitative, drawing on the perspectives of key informants—individuals who play an important role in formulating and implementing reproductive health policies and plans. -

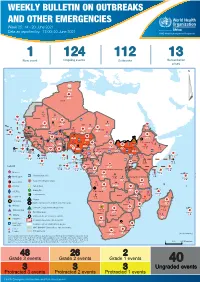

Weekly Bulletin on Outbreaks

WEEKLY BULLETIN ON OUTBREAKS AND OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 25: 14 - 20 June 2021 Data as reported by: 17:00; 20 June 2021 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR Africa WHO Health Emergencies Programme 1 124 112 13 New event Ongoing events Outbreaks Humanitarian crises 64 0 135 928 3 631 Algeria ¤ 36 13 936 0 6 045 181 Mauritania 14 381 524 48 0 110 0 42 404 1 158 Niger 20 336 481 5 362 19 Mali 21 0 9 0 Cape Verde 6 471 16 4 946 174 Chad Eritrea Senegal 5 469 193 Gambia 3 0 66 0 32 002 283 1 414 8 Guinea-Bissau 847 17 Burkina Faso 236 49 275 194 4 283 167 155 2 117 Guinea 13 469 167 13 0 3 825 69 1 1 30 0 Benin 198 0 Nigeria 1 063 4 6 0 1 0 Ethiopia 13 2 6 995 50 556 5 872 15 Sierra Leone Togo 530 0 80 090 1 310 Ghana 7 139 98 Côte d'Ivoire 10 786 115 19 000 304 68 0 South Sudan 45 0 Liberia 199 2 17 0 Central African Republic 1 308 2 0 25 0 50 14 0 6 738 221 Cameroon 23 450 289 3 0 48 044 308 94 913 793 34 135 194 7 0 56 0 1 347 30 3 1 620 1 178 078 3 437 2 0 168 0 4 816 82 13 721 128 2 0 8 698 120 Equatorial Guinea Uganda 356 0 822 9 Sao Tome and Principe 4 0 2 995 95 71 543 660 Kenya Gabon Legend Congo 2 682 83 305 26 Rwanda 8 140 103 2 362 37 30 048 378 24 736 156 Democratic Republic of the Congo 12 298 161 Burundi Measles 5 242 8 Seychelles 37 809 879 427 0 Humanitarian crisis 536 32 Monkeypox United Republic of Tanzania 197 0 14 549 52 Suspected Drancuculiasis Lassa fever 509 21 63 1 6 257 229 Cholera Yellow fever 37 678 859 129 003 1 644 Comoros Meningitis 304 3 cVDPV2 Angola Malawi Leishmaniasis 34 868 1 168 726 0 3 908 146 Zambia 133 0 COVID-19 Mozambique -

HS2020 Technical Report Template

better systems, better health HEALTH SYSTEMS 20/20 FINAL PROJECT REPORT September 2012 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by the Health Systems 20/20 project. Health Systems 20/20 is USAID‘s flagship project for strengthening health systems worldwide. By supporting countries to improve their health financing, governance, operations, and institutional capacities, Health Systems 20/20 helps eliminate barriers to the delivery and use of priority health care, such as HIV/AIDS services, tuberculosis treatment, reproductive health services, and maternal and child health care. September 2012 For additional copies of this report, please email [email protected] or visit our website at www.healthsystems2020.org Cooperative Agreement No.: GHS-A-00-06-00010-00 Submitted to: Scott Stewart, AOTR Health Systems Division Office of Health, Infectious Disease and Nutrition Bureau for Global Health United States Agency for International Development Recommended Citation: Health Systems 20/20 project. September 2012. Health Systems 20/20 Final Project Report. Bethesda, MD: Health Systems 20/20 project, Abt Associates Inc. Cover Photo: David Page Abt Associates Inc. I 4550 Montgomery Avenue I Suite 800 North I Bethesda, Maryland 20814 I P: 301.347.5000 I F: 301.913.9061 I www.healthsystems2020.org I www.abtassociates.com In collaboration with: I Aga Khan Foundation I Bitrán y Asociados I BRAC University I Broad Branch Associates I Deloitte Consulting, LLP I Forum One Communications I RTI International I Training Resources Group I Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine 2 HEALTH SYSTEMS 20/20 FINAL PROJECT REPORT DISCLAIMER The author‘s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) or the United States Government CONTENTS Acronyms ..................................................................................... -

COMMUNITY HEALTH POLICIES and PROGRAMMES Publication: October 2019 © Cover Photo: Tremeau/Fonds Français Muskoka ANALYSIS REPORT

ANALYSIS REPORT COMMUNITY HEALTH POLICIES AND PROGRAMMES Publication: October 2019 © cover photo: Tremeau/Fonds Français Muskoka ANALYSIS REPORT COMMUNITY HEALTH POLICIES AND PROGRAMMES ACRONYMS AC Care community agents (in French: Agents EBV Epstein-Barr virus communautaires - Sénégal) ECD Early Childhood Development ACPP Prevention and Promotion Community Actor (in French: Acteur Communautaire de Prévention et de Promotion EMTCT Elimination of mother-to-child transmission of VIH - Sénégal) FGM Female Genital Mutilation ACT Artemisinin-based combination therapy GAC Global Affairs Canada (ex-CIDA) ANC Antenatal Care HPV Human papilloma virus APP Agents for Promotion and Prevention (in French: iCCM integrated Community Case Management Agents pour la Promotion et la Prévention - Niger) IMCI Integrated Management of Childhood Illness ARI Acute Respiratory Infection IPTp Intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy ASACO Community Health Organizations (Mali) KMC Kangaroo Mother Care ASBC Community-based health workers (in French : Agent de santé à base communautaire - Burkina Faso) LGA Local Government Area (Nigeria) BEPC First Secondary school diploma in francophone LLI(T)N Long-lasting insecticidal(-treated) nets education systems - 14/15 years old (in French: Brevet d’Etudes du Premier Cycle) LMIS Logistics management and information system CAC Community organization unit (in French: Cellule MAM Moderate acute malnutrition d’animation communautaire - DRC) M&E Monitoring and Evaluation CBC Community Birth Companion (The Gambia) MNP Micronutrient -

Rapid Assessment of the Health System in Benin, April 2006

Rapid Assessment of the Health System in Benin, April 2006 Grace Adeya Alphonse Bigirimana Karen Cavanaugh Lynne Miller Franco Printed: February 2007 Rapid Assessment of the Health System in Benin, April 2006 This report was made possible through support provided by the U.S. Agency for International Development. The opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Agency for International Development. About RPM Plus RPM Plus works in more than 20 developing and transitional countries to provide technical assistance to strengthen pharmaceutical and health commodity management systems. The program offers technical guidance and assists in strategy development and program implementation both in improving the availability of health commodities—pharmaceuticals, vaccines, supplies, and basic medical equipment— of assured quality for maternal and child health, HIV/AIDS, infectious diseases, and family planning and in promoting the appropriate use of health commodities in the public and private sectors. About MEASURE Evaluation MEASURE Evaluation is a project funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and implemented by the Carolina Population Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partnership with Tulane University, ORC Macro International, John Snow, Inc., and Constella Futures. As a key component of USAID’s Monitoring and Evaluation to Assess and Use Results (MEASURE) framework, the project promotes a continuous cycle of data demand, collection, analysis and utilization to improve population and health conditions. Since 1997, MEASURE Evaluation has worked around the world to strengthen the capacity of host-country programs to collect and use population and health data. -

Weekly Bulletin on Outbreaks

WEEKLY BULLETIN ON OUTBREAKS AND OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 19: 3-9 May 2021 Data as reported by: 17:00; 9 May 2021 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR Africa WHO Health Emergencies Programme 1 128 115 13 New event Ongoing events Outbreaks Humanitarian crises 64 0 124 104 3 328 Algeria ¤ 36 13 672 0 4 0 5 929 175 Mauritania 7 2 14 108 500 110 0 7 0 995 54 18 448 455 Niger Mali 9 0 3 742 12 567 0 6 0 2 079 4 4 877 171 Cape Verde 40 692 1 119 Chad Eritrea Senegal 5 074 189 61 0 Gambia 27 0 3 0 26 441 232 1 226 7 847 17 Guinea-Bissau 236 49 7 0 262 702 3 888 Burkina Faso 165 419 2 065 13 379 162 12 0 3 741 67 Guinea 23 12 1 1 30 0 Benin 1 873 72 0 Nigeria Ethiopia 13 2 556 5 4 0 6 995 50 3 473 296 6 188 15 Sierra Leone Togo 74 733 1 144 6 674 93 52 14 Ghana Côte d'Ivoire 10 637 115 14 484 479 149 2 17 0 65 0 South Sudan 40 0 Liberia Central African Republic 1 307 2 49 0 97 17 25 0 22 633 150 14 0 46 442 291 92 951 783 Cameroon 3 0 0 7 28 676 137 56 0 1 018 20 3 1 163 554 2 895 597 1 132 0 124 1 488 6 4 057 79 13 154 7 694 112 1 0 1 0 Equatorial Guinea Uganda 3 0 2 0 542 8 2 066 85 Sao Tome and Principe 42 384 346 Kenya 32 11 Legend 7 884 100 Gabon Congo 2 012 73 Rwanda Humanitarian crisis 2 318 35 25 652 338 Measles 23 432 143 Democratic Republic of the Congo 11 343 148 Burundi Ebola virus disease 4 200 6 Monkeypox Seychelles 30 323 772 564 0 420 29 Skin disease of unknown etiology United Republic of Tanzania Lassa fever 191 0 6 811 28 Yellow fever 509 21 Cholera 63 1 6 257 229 Dengue fever 28 740 663 92 092 1 257 cVDPV2 Leishmaniasis Comoros Angola Malawi -

Women's Reproductive Rights in Benin

Women’s Reproductive Rights in Benin: A Shadow Report www.reproductiverights.org WOMENS REPRODUCTIVE RIGHTS IN BENIN: A SHADOW REPORT Published by: The Center for Reproductive Law and Policy 120 Wall Street New York, NY 10005 USA © 1999 The Center for Reproductive Law and Policy (CRLP) Any part of this report may be copied, translated, or adapted with permission from CRLP, provided that the parts copied are distributed free or at cost (not for prof- it), and CRLP and the respective author(s) are acknowl- edged. Any commercial reproduction requires prior written permission from CRLP. The authors would appreciate receiving a copy of any materials in which information from this report used. Table of Contents Reproductive Rights of Young Girls and Adolescents in Benin A. The Reproductive Health and Rights of Young Girls and Adolescents Page (Articles 6 and 24 of the Children’s Convention) 3 1. Fertility of Adolescent Girls and Their Access to Reproductive Health Care, Including Family Planning and Safe Motherhood 3 2. Abortion 6 3. HIV/AIDS and Sexually Transmissible Infections (STIs) 7 B. The Right to Education (Articles 17,24 (2)(e), 28 and 29 of the Children’s Convention) 8 1. Access to Basic Education without Discrimination 8 2. Access to Sex Education 10 C. Marriage of Young Girls and Adolescents (Article 2 of the Children’s Convention) 11 1. Minimum Age of Marriage 11 D. Sexual and Physical Violence Against Young Girls and Adolescents (Articles 19 and 34 of the Children’s Convention) 12 1. Sexual Violence 13 2. Female Circumcision/Female Genital Mutilation (FC/FGM) 13 Reproductive Rights of Young Girls and Adolescents in Benin Introduction The purpose of this report is to supplement, or “shadow,” the report of the government of Benin to the Committee on the Rights of the Child (hereinafter the Committee) during its 21st ses- sion. -

Post-Cairo Reproductive Health Policies and Programs: a Study of Five Francophone African Countries

Post-Cairo Reproductive Health Policies and Programs: A Study of Five Francophone African Countries Justine Tantchou Ellen Wilson August 2000 POLICY is a five-year project funded by the u.s. Agency for Intemational Development, under Contract No. CCP-C-O~95-00023--04, beginning September 1, 1995. The project is implemented by The Futures Group Intemational in collaboration with Research Triangle Institute (RTO and The Centre for Development and Population Activities (CEDPA). '--14lh ~-~: H ••••••• , .11111' The POLICY Project Justine Tantchou Ellen Wilson August 2000 Photo Credits All photos are printed with pennission from the JHU/Cenrer for Commwzication Programs. Contents iv Preface v Acknowledgments vi Executive Summary vii Abbreviations 1 Introduction 3 Reproductive Health Context in the Five Countries 5 The Policy Process: Definitions of Reproductive Health, Policies, and Priorities 15 Participation, Support, and Opposition 21 Policy Implementation 28 Financial Resources for Reproductive Health 33 Summary and Conclusion 37 Appendix 44 References Preface The mission of the Network for Reproductive Health Research in Africa (RESAR) is to improve reproductive health through research and training. The organization receives grants for operations under project performance contracts with governmental and nongovernmental organizations as well as with bilateral and multilateral donors involved in reproductive health. RESAR is currently made up of 10 national units in Francophone Africa called CRESARs. The goal of the POLICY Project is to create supportive policy environments for family planning and reproductive health programs, including HIV/AIDS, through the promotion of a participatory policy process and population policies that respond to client needs. The project has four components-policy dialogue and formulation, participation, planning and finance, and research- and is concerned with crosscutting issues such as reproductive health, HIV/AIDS, gender, and intersectoral linkages. -

Benin Strategy Matrix

Global Health Initiative: Benin Country Strategy Photos by Charlie Darr, US Peace Corps DOS, USAID, CDC, Peace Corps, USDA, USADF, DOD November 2011 Table of Contents Map of Benin…………………………………………………………………………………….…………3 List of Acronyms and Translations…...………………………………………………………………..…..4 GHI Vision for Benin .................................................................................................................................. ..6 Benin Health Context and Priorities ............................................................................................................. 7 GHI Objectives, Program Structure and Implementation ........................................................................... 10 Monitoring and Evaluation and Learning ................................................................................................... 19 Communications and Management Plan ..................................................................................................... 21 Linking High-Level Goals to Programs. .................................................................................................... .22 Annex 1. Benin GHI Country Strategy Results Framework ....................................................................... 25 Annex 2 GHI Benin Strategy Matrix .......................................................................................................... 26 2 Figure 1. Map of Benin 3 List of Acronyms ABMS Association Béninoise de Marketing Social (Beninese Social Marketing Association) ABPF Association -

Benin Malaria Operational Plan FY 2016

This Malaria Operational Plan has been approved by the U.S. Global Malaria Coordinator and reflects collaborative discussions with the national malaria control programs and partners in country. The final funding available to support the plan outlined here is pending final FY 2016 appropriation. If any further changes are made to this plan it will be reflected in a revised posting. PRESIDENT’S MALARIA INITIATIVE Benin Malaria Operational Plan FY 2016 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS and ACRONYMS ....................................................................................... 3 I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................... 5 II. STRATEGY ............................................................................................................................. 9 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 9 2. Malaria situation in Benin .................................................................................................. 10 3. Country health system delivery structure and Ministry of Health (MoH) organization .... 11 4. National malaria control strategy ....................................................................................... 12 5. Updates in the strategy section .......................................................................................... 15 6. Integration, collaboration, and coordination .....................................................................